|

Golden fresco of Madonna and Child with Constantine the Great

and the empress Theodora, Aya Sofya |

Saturday, August 28.

Susanne and I barely got any sleep last night. The music at the disco downstairs kept us writhing in our beds until well past 3am. We were both extremely irritable and ready to find a new place to stay. Trying to save a few bucks by sleeping a hostel had turned out to be a terrible idea. I guess we were no longer the low-budget backpackers we once were. We would desperately need a good night's rest tonight, and the Orient Hostel was definitely not the place to get it. Susanne and I agreed to go out and find another hotel after breakfast.

As we got dressed Susanne noticed a piece of paper that had been stuck under our door during the night:

Susanne and Andy: I was in Sultanahmet last night

last night

so I tried stopping by the Orient to see if you wanted

to go out. Give me a call when you can. -Aydin, 22:35

Apparently our one connection in Istanbul had unsuccessfully tried contacting us. Susanne and I both felt terrible. We hadn't gotten around to tracking down Aydin first, and it never occurred to us that he would go out of his way to come to the hostel to find us first. As soon as we could settle down into another hotel we would give him a call and make plans to get together -- assuming we hadn't become personae non gratae.

We ate breakfast on the rooftop cafe, happy to see that the skies were no longer obscured by water-logged rainclouds. Breakfast at the Orient consisted of a fresh baguette, jam, yogurt and Nescafe. It wasn't the grandest breakfast I'd ever had but it would tie us over for the morning. As Susanne lingered over her cup of coffee I decided to go downstairs to let the staff know we were checking out tonight. The man at the front desk sympathized with our plight but said we couldn't get our money back for the second night because of their no-refunds policy. I argued with him for a while, insisting we had been promised a room that would be quiet and away from the disco, but he pleaded ignorance. There was no way I would have put up with a second night in this grimy dump so left the hostel in search of better accommodations.

I was aware of several medium-range hotels in the area that were probably worth visiting. The closest one was the Alp Guesthouse, just around the corner from the Orient. The Alp seemed like a comfortable place but I realized that it was parallel to the Orient's disco. The management at the Alp promised me that you couldn't hear the disco from their rooms, but I had heard that before when making our reservations at the Orient. My search would have to continue.

Two blocks north of the Orient I reached the Four Seasons Hotel, an Ottoman mansion restored to a luxury four-star with uniformed doormen standing guard over its bright yellow walls. While the Four Seasons itself was well out of our price range, I found several small guesthouses across the street. One of these, the Ottoman Guesthouse, appeared to suit our needs. The Ottoman's Iranian manager, Reza, showed me a spacious triple with air conditioning and private bath.

"It's $35 a night," he quoted as I looked around the room, testing the air conditioner and the light switches. Before I had a chance to respond, Reza lowered the price to $30. It seemed like a bargain for a good night's sleep in a hotel only one block from Aya Sofya, so I paid for the first night and returned to the Orient to tell Susanne of our impending move.

so I paid for the first night and returned to the Orient to tell Susanne of our impending move.

Before leaving the Orient we paid a visit to its in-house travel agency to buy our airline tickets for Izmir and Van. The agent was running late that morning, but an Australian backpacker suggested we go across the street to its partner travel agency. After taking our backpacks uphill to the Ottoman Guesthouse we went to the second travel office, chatting with the agent and a friend who ran a hotel on the Aegean coast. The friend, Hakim, was engaged to an American woman and spoke excellent English. He was a former tour guide and strongly encouraged us to travel as far as possible into eastern Anatolia.

"The further you go the less tourists you will see," he said. "By the time you get to Mount Ararat you will have all of it to yourself."

"Will we be able to visit Nemrut Dagi?" I asked, worried that the Turkish-Kurdish conflict had closed the mountaintop ruins as one recent travel book had suggested.

"No problem at all," Hakim replied. "Nemrut Dagi is open to visitors. On a good day there will only be you and your guide on the summit. Other days there are maybe 20 or 30 people on top. Either way it is wonderful. Nemrut Dagi is probably my favorite place to visit in Turkey."

Hakim's encouragement sealed our plans. On Sunday we would fly to Izmir, staying the night in Selçuk before visiting the Greco-Roman ruins of Ephesus. From there we would work our way to the rock valleys of Cappadokia, four hours east of Ankara, and spend at least two days exploring the region's Byzantine monastery caves. We would then have to find a way to get to Nemrut Dagi -- it was at least a nine-hour drive from Cappadokia to the village closest to Nemrut. Once we had climbed Nemrut for sunrise, we'd continue south towards the Syrian border and the city of Urfa, the legendary birthplace of Abraham and the center of the medieval crusader kingdom of Edessa.

We would then travel into the heart of Kurdistan, to the city of Van. Van would serve as our base as we visited the sacred Armenian ruins of Akdamar Island and the 18th century Kurdish palace of Ishak Pasa, located near the town of Dogubeyazit in the shadow of Mount Ararat. We planned to give ourselves three full days around Van, since we would probably have to make private arrangements to visit each site. The war against the Kurdish PKK guerrillas had all but destroyed eastern Anatolia's tourism industry so we would not be able to count on organized day-tours run by local agencies. After squeezing in as much as we could in Kurdistan we would then fly back to Istanbul for three final nights in Turkey.

Susanne and I were both satisfied with the itinerary. We had each had to make a couple of sacrifices -- Susanne had pushed for a day in Antioch while I had hoped to go to northeastern Anatolia to visit the ancient Armenian capital of Ani. All things considered, we were planning to fit in a hell of a lot of history in a short period of just two weeks. I would be amazed if we managed to visit everything we had hoped.

The travel agent made our reservations and asked us to stop by after lunch to pick up our tickets, which would be couriered from the airline office. Now that Susanne and I had completed our major transport arrangements we were free to wander Old Istanbul. Our two primary goals for the day were Aya Sofya and the Blue Mosque, which were both less than a two-minute walk from the hotel. Later in the day we hoped to visit the Egyptian Spice Bazaar and perhaps track down the Rüstem Pasa Camii, a small mosque known for its intricate blue tilework, for which we had search in vain the previous day. We both knew it was an ambitious itinerary for one day, but Susanne and I felt confident we could do them justice without killing ourselves in the process.

a small mosque known for its intricate blue tilework, for which we had search in vain the previous day. We both knew it was an ambitious itinerary for one day, but Susanne and I felt confident we could do them justice without killing ourselves in the process.

|

| Aya Sofya (Hagia Sophia) |

Outside Aya Sofya, Susanne and I agreed it would be worthwhile to hire a guide for our visit. The greatest church in the ancient world boasted over 1400 years of history, much of which probably would not have been conveyed if we chose to rely solely on our guide book. After paying the five million lira entrance fee we were approached by several guides, all of whom sported laminated badges displaying their certification by the state tourism agency and their language skills. We soon selected Mustafa, an elderly gentleman with a disarming smile who noted he had been giving Aya Sofya tours for over 30 years.

"After you, my dear lady," he said to Susanne with a slight bow of the head, pointing the way to the main gate.

Susanne and Mustafa hit it off immediately, striking up a conversation as I gazed upwards towards the church's imposing red brick façade. "Susanne is a Turkish name, you know," he said to Susanne after she introduced herself.

Mustafa, it turned out, was actually a Bulgarian Turk born outside of Sofia. Though now considered Slavs, the Bulgars were originally a group of Turkic tribes, many of which adopted Christianity and assimilated with the Slavic tribes west of the Black Sea. The Ottomans controlled Bulgaria for several centuries, settling many Ottoman Turks in the region. Mustafa's family fled Bulgaria in the 1920s as the Ottoman Empire gave out its last gasp. Their defeat in World War I led to a complete redrawing of the Balkan map, including fully independent kingdoms of Greece, Romania, Yugoslavia and Bulgaria. Mustafa's family concluded its fortunes lay in the newly formed Republic of Turkey rather than the Orthodox Christian nation of Bulgaria, so they settled in Istanbul when he was a child.

"It was a long time ago," Mustafa explained, "but Istanbul is my true home."

Just inside the main entrance we found ourselves standing under a golden Byzantine mural of Jesus the Pantocrator, shining as if it had been gilded yesterday.

|

| Aya Sofya mural of Jesus the Pantocrator |

"This is the imperial entrance of Aya Sofya," Mustafa explained. "Only the Emperor Justinian could come through these doors. As he would enter, the Imperial guard would stand on each side of the door. They would make sure that this door was for the emperor's use only. They stood guard at all times. During the winter it would get cold and they would stomp their feet to stay warm. You can see the indentations in the marble floor left by their stomping."

Passing through the imperial gate we entered the main hall of Aya Sofya. For more than a thousand years, the hall was the largest enclosed space in the world. Susanne and I had both visited countless cathedrals in previous travels so we were well acquainted with the awe-inspiring elegance of holy spaces soaring heavenward. But Aya Sofya was different -- its openness extended in all directions under a dome so vast you half expected to encounter the brilliant shimmer of stars above.

On the back wall of the church, tall stained glass windows shone beams of light onto the floors below. Mosaics and murals covered much of the marble, including what appeared to be explosions of feather plumes. These must the Islamic angels that were added after Mehmet II conquered Constantinople in 1453. Because Islam forbids the portrayal of human figures in art, Aya Sofya's angels were more metaphorical expressions of angelic grace rather than the human-like figures we would expect in Western art.

The left side of the hall was filled with scaffolding whose skeleton extended hundreds of feet to the ceiling. For a brief moment I was disappointed by the sight of the scaffolding but it made me appreciate the genius of Aya Sofya's construction. Today it takes a high-tech lattice of metalwork to allow workers to renovate and restore the highest points in the church; imagine the determination of the Byzantines as they first constructed the church over 1500 years ago! No wonder Justinian was able to proclaim after completing his Hagia Sophia in 537 AD, "Solomon! I have outdone you!" Arrogance may be the mandate of every autocrat, but in this particular case Justinian could not have been more justified.

We walked with Mustafa to a series of stone rings embedded in the marble floor. "This is the Omphalion, where the Byzantine emperors were coronated," Mustafa explained. "The emperor would stand in the largest circle, his heir and family in the next largest, then the members of his court. The less important you were the smaller the circle you got. "

Mustafa pointed to a series of enormous wooden discs on the walls, each adorned with Arabic script. "These discs were added in the 19th century, when Aya Sofya was still a mosque," he said. "You can read the names of Allah and Muhammad on the largest discs, as well as the names of the four great caliphs who followed Muhammad: Abu Bakr, 'Umar, 'Uthman and 'Ali. Aya Sofya is no longer a mosque, though. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk made it a national museum in 1935. But the discs remain in tribute to this day."

On the back wall Mustafa pointed to what appeared to be an off-centered shrine. "The reason this is not centered is because it points to Mecca," he explained.

"It's the mihrab, right?" Susanne asked.

"Yes, yes," Mustafa replied approvingly. "The mihrab shows us which direction to pray, since we Muslims must pray towards Mecca five times every day."

|

Anatolian Trivia

Like the Egyptians and the Romans before them, the Byzantine Greeks adored the rare, blood-red marble known as porphyry. Most of Constantinople's porphyry columns originally resided in Roman temples along the Aegean and were swiped by the Byzantines, for it was too expensive to mine the marble in far-away Egypt. But many of these columns didn't stay in the city for long. When the Venetians sacked Constantinople during the ironically-named Fourth Crusade in 1204, they brought home a fortune in Byzantine booty. Their most famous plunder, the bronze quadriga horses from Constantinople's Hippodrome, sit atop St. Mark's Basilica in Venice. But if you stand in front of St. Mark's today, you'll also notice that some of its columns don't match the rest. The reason is simple -- they're some of the porphyry columns plundered from Constantinople.

|

"You know Islam well," he added, smiling. "Now I will listen and you can give the tour!"

"Bahsis, lütfen," I said jokingly to him, putting out my hand for Susanne's well-earned tip.

We stood awhile under the main dome, admiring the intricate carvings of the marble balcony where Justinian once sat. Not far from it also stood the minbar, the high stone pulpit added by the Ottomans to allow the imam to deliver his Friday sermons. Just around the corner Mustafa led us past tall columns made of a beautiful red marble.

"These columns are porphyry, a unique stone found only in Egypt," Mustafa explained. "They are much older than Aya Sofya. They were used in Roman temples along the Aegean, at Ephesus, Didyma and Miletus. Because the stone was so rare it was easier for Justinian to bring the columns from the great Temple of Artemis in Ephesus rather than cut new ones in Egypt."

Not far from the colonnade, Mustafa pointed out what appeared to be giant marble vases. "These are cisterns, added to Aya Sofya by Sultan Murad III in the 16th century," he noted. "In Islam, it is important to cleanse yourself before praying. You must wash in order to be pure before Allah. The cisterns hold hundreds of gallons of water, and the coolness of the marble keeps the water refreshing year round."

"Today it is very warm outside, but touch the marble," Mustafa encouraged us. The marble indeed was cold, almost as if it was refrigerated.

Mustafa wrapped up the tour by leading us down a stone corridor, towards the main exit. "Most people leave through here thinking the tour is over," he said. "But if you do not pay attention you may miss something beautiful. Look behind you."

On the back wall, high above the archway, we found a glorious 10th century gilded mosaic of the Madonna and Child, framed with the visages of Constantine the Great on the left and Justinian on the right.

"So many people walked out of Aya Sofya without seeing this mural, they decided to place a large mirror at the far end of the hallway," Mustafa said. "You might say they saved the best for last!" Turning around yet again, we noticed the large mirror above the exit. From where we were standing you couldn't see anything in particular on it, but as we approached the exit, the golden mosaic appeared like an apparition.

"So now I end the tour here," Mustafa concluded. "If you would like you can visit the gallery upstairs where you can find more murals. I can give you a separate tour of the mosaics for another five million lira or you can visit them on your own. It's up to you." While Susanne and I had both enjoyed Mustafa's company and felt the tour was worth every penny, taking a second tour for an extra $13 just to visit two or three mosaics didn't seem worth it. We thanked Mustafa for his tour and paid him before heading upstairs on our own.

We climbed a tight stone corridor up several flights before reaching the upper gallery. The gallery offered a tremendous view of the main hall, along with the mosaics Mustafa had promised. One particularly impressive 14th century mosaic depicted Jesus, the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist. A short walk soon brought us to the dazzling 11th century mosaic portrait of the Empress Zoe. For centuries these mosaics were painted over with whitewash during the time when Aya Sofya served as a mosque. This whitewash, ironically, preserved the mosaics for the ages. Centuries of grime and soot were kept away from these gilded wonders by just a simple coat of paint.

We soon returned to the ground floor and exited Aya Sofya, heading towards Sultanahmet Gardens and the Blue Mosque. Susanne snapped a picture of an old man selling fez hats; he smiled and waved as we passed through the garden. I was very eager to visit the Blue Mosque, formally known as the Sultanahmet Camii but called the Blue Mosque because of its blue tile interior. Istanbul is a city of mosques, with plenty of them laying claim to being the largest, the tallest, or the oldest. But from my point of view, the Blue Mosque was Istanbul's most exquisite. It had to be the most beautiful mosque, I suppose, since Sultan Ahmet I decided to build it so close to Aya Sofya, forever linking his mosque visually to one of the greatest architectural achievements in Christianity. The Blue Mosque was constructed as Sultan Ahmet's response to Aya Sofya -- a demonstration that the Ottomans could build a structure that could also claim to out-do Solomon.

|

| The Blue Mosque (Sultanahmet Camii)

|

From the outside, the Blue Mosque is a graceful complement to Justinian's church. It is a classical Ottoman mosque that blends the enormity of Aya Sofya's Romanesque style with delicate Islamic architecture. An evolving series of half domes leads towards a splendid upper dome. Six minarets define its outer borders; one minaret on each corner, with two more minarets towering above the main courtyard gate. A wide swath of fishnet wiring dangled between two minarets. During they day the net looked as if it were laying it wait for a passing commuter plane, but its function became apparent at night when it turned into a giant illuminated sign marking the 700th anniversary of the founding of the Ottoman Empire.

define its outer borders; one minaret on each corner, with two more minarets towering above the main courtyard gate. A wide swath of fishnet wiring dangled between two minarets. During they day the net looked as if it were laying it wait for a passing commuter plane, but its function became apparent at night when it turned into a giant illuminated sign marking the 700th anniversary of the founding of the Ottoman Empire.

|

| Main courtyard, Blue Mosque |

Susanne and I entered Sultanahmet's courtyard from the side and walked towards the inner mosque. A vinyl curtain hung over the main entrance, with a sign indicating that only Muslims could enter through that gate. We would have to go around to the back of the mosque and enter through a secondary door. We walked across the marble courtyard and cut around the back, where an attendant gave us plastic bags in which to carry our shoes. A handful of tourists were being asked to wear linen wraps around their legs because they were trying to enter the mosque in shorts. Since Susanne and I were more appropriately attired we had no problem going inside.

We walked inside the mosque's visitors gallery: a carpeted hall occupying the back quarter of the sanctuary, separated from the rest of the mosque by a retractable wooden gate. Muslims who entered through the main doorway were allowed to pass through the gate and pray wherever they wished. Blue Iznik tiles covered the walls in geometric patterns as an enormous Ottoman chandelier, over 100 feet in diameter, hung in the mosque's center just out of reach, dangling from long ceiling cables. At the far end of the mosque a mirhab pointed the faithful towards Mecca, with a small piece of Mecca's qa'aba stone embedded in its wooden frame.

stone embedded in its wooden frame.

I felt a little awkward as I admired the mosque's beauty. On both sides of the wood gate several Muslims were praying, kneeling on the red carpet. Though they didn't seem distracted by our presence, I wanted to make sure we didn't interfere with their activities. I sat quietly near the center of the gate observing the hundreds of electric lamps glowing on the broad chandeliers, trying to envision the days when imams would kindle the wicks of each oil lamp, slowly making their way around the perimeter of the chandelier. The chandelier must have been several hundred feet in circumference. Igniting it must have been a holy exercise in its own right.

|

| Ottoman chandelier inside the Blue Mosque

|

Several large groups of Turks eventually came inside to pray, so Susanne and I took this as our cue to wrap up our visit. We put on our shoes along the mosque's outer steps as an attendant accepted donations for the mosque's upkeep. I left two million lira inside his box as we left. We were both a little hungry at this point so we walked along Divan Yolu Caddesi to find some lunch. We settled in at a pideci

to find some lunch. We settled in at a pideci that sold both Turkish and western pizzas. Susanne and I both ordered Turkish pizzas with vegetables and two bottles of Sprite. The waiter, a young man in his twenties, cracked jokes in broken English as we ordered. Later as we ate our pizzas he noticed me fiddling with my portable tape recorder, which I had used earlier to record a call to prayer.

that sold both Turkish and western pizzas. Susanne and I both ordered Turkish pizzas with vegetables and two bottles of Sprite. The waiter, a young man in his twenties, cracked jokes in broken English as we ordered. Later as we ate our pizzas he noticed me fiddling with my portable tape recorder, which I had used earlier to record a call to prayer.

"Is that a radio?" our waiter asked.

"It's a tape recorder," I replied. I hit the play button and played a few seconds of tape.

"Give it to me," he asked abruptly, holding out his hand. Even though I had no idea what he was going to do, I handed it over. He immediately began to play with its buttons, rewinding and fast-forwarding the tape like a little boy getting his first Walkman for Christmas.

"I will be back," he then said, walking away with the recorder. Susanne and I looked at each other and shrugged, wondering why he was bringing it inside. It's not like Istanbulu Turks have never seen tape recorders before, I thought to myself. A moment or two later the waiter returned with a big smile on his face. He hit the play button and began blasting Turkish pop music. At first I thought he had put in one of his own tapes.

|

Turkish Pronunciation

Interested in learning how to pronounce the Turkish words mentioned in this journal? Check out my Turkish pronunication guide!

|

"I have recorded music for you," he said. "Now you can play good Turkish music for your friends." Apparently someone in the kitchen was listening to a radio station, so the waiter had held up the tape player and recorded some of it.

"Tesekkürler," I said, thanking him.

I said, thanking him.

"Bir Sey degil," he replied. "Türkçe konüsüyormüsünüz?"

he replied. "Türkçe konüsüyormüsünüz?"

"Biraz Türkçe," I answered, somewhat proud that I had understood his question of whether I spoke Turkish. I opened up a can of worms by doing so, though, for he began to speak rapidly in Turkish.

I answered, somewhat proud that I had understood his question of whether I spoke Turkish. I opened up a can of worms by doing so, though, for he began to speak rapidly in Turkish.

"Üzgünüm," I responded meekly. "Anlamadim."

I responded meekly. "Anlamadim."

"I asked you where did you learn your Turkish," he laughed.

"Oh, Türkçe kitablar," I answered.

"Books!," the waiter exclaimed. "A good start. Keep speaking to people and your Turkish will soon become better than my English."

"I doubt that," I replied with a grimace.

After lunch, Susanne and I decided to spend the afternoon conducting a walking tour of Eminönu, the Istanbul neighborhood stretching from north of Sultanahmet to the waters of the Golden Horn. We had several major goals for the rest of the day, including the Egyptian spice bazaar and two exquisite mosques designed by Ottoman master architect Mimar Koca Sinan: Suleymaniye Camii and Rüstem Pasa Camii. We winded our way through the alleyways behind Divan Yolu Caddesi in a neighborhood traditionally known for its small publishing companies. Shop windows advertised Qurans, children's books, college texts, many of which were probably printed in the local press rooms. The road took a downhill turn past the Iranian consulate, giving us a brief glimpse of the Golden Horn far beyond the rooftops.

|

| Flag salesman, Istanbul |

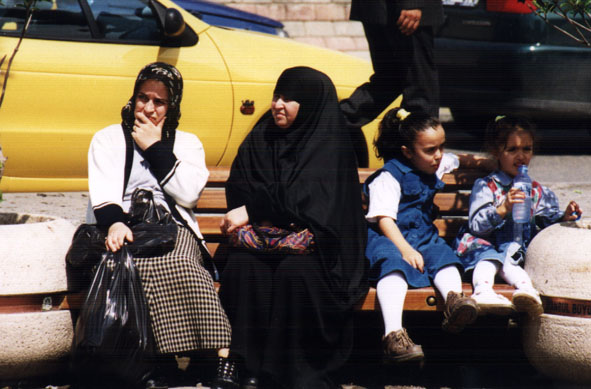

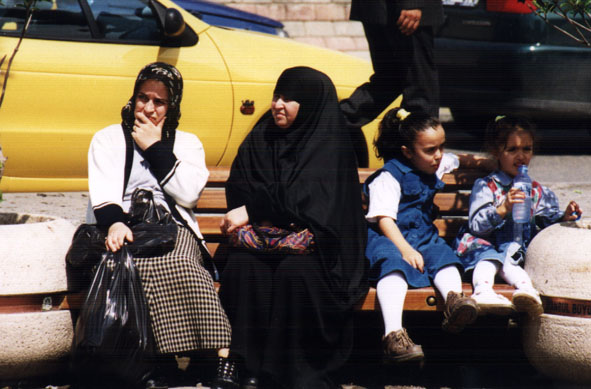

A small map in hand, I suggested we take a left in order to head more directly to the Egyptian spice bazaar. The narrow cobblestone alleyway was a step back in time when compared the bustling commercial publishing district. Susanne and I could hear the bustle of shoppers not far ahead. The alley opened up into a larger intersection that was populated with hundreds of shoppers meandering along a variety of market stalls: textiles, fruit, used books, hardware tools. Compared with the Turks we had seen wandering touristy Sultanahmet, the shoppers here were much more conservatively dressed, with many women in headscarves and men in skullcaps. A number of women were covered from head to toe in black chadors. At first I thought most of these women were older but as I got closer and saw their faces I could see they were probably in their 30s and 40s. In the middle of the intersection a man stood draped in large red flags. Beyond him I could see another man, exchanging money with a family for one of his flags. I had never seen people selling flags on a street corner before, but considering how fiercely proud most Turks are over their republic it seemed like a profitable business.

Susanne and I made our way through the throng of shoppers, squeezed on and off the sidewalk by oncoming traffic. The streets were so congested it must have taken ten minutes just to get to the end of the next block, where we found the entrance to the Misir Kapali Çarsisi, the Egyptian spice bazaar. At first glance the market was not unlike its more famous sibling in Sultanahmet. But unlike the Kapali Çarsi, the Egyptian bazaar still catered to local needs. For centuries, Istanbulus have come here to shop for all of their spice and medicinal needs. Even today, spices still serve a duel purpose as flavorings and herbal medicines, offering remedies to ills ranging from stomach aches to impotence. While I spotted several tourists among the crowds, the majority of shoppers browsing the market appeared to be Turks. Most stores carried a similar assortment of spices arranged in large burlap sacks outside the window. Men would try to lure us into their shops by offering us trays of candy samples, usually chewy morsels of dried fruit, honey and pistachios.

the Egyptian spice bazaar. At first glance the market was not unlike its more famous sibling in Sultanahmet. But unlike the Kapali Çarsi, the Egyptian bazaar still catered to local needs. For centuries, Istanbulus have come here to shop for all of their spice and medicinal needs. Even today, spices still serve a duel purpose as flavorings and herbal medicines, offering remedies to ills ranging from stomach aches to impotence. While I spotted several tourists among the crowds, the majority of shoppers browsing the market appeared to be Turks. Most stores carried a similar assortment of spices arranged in large burlap sacks outside the window. Men would try to lure us into their shops by offering us trays of candy samples, usually chewy morsels of dried fruit, honey and pistachios.

Though neither of us had any intention of buying any spices, Susanne and I both accepted a taste of candy from one shop owner and walked inside his store. To the right I found wooden boxes of dark broken leaves, all with the word çay scribbled in ink pen on a slip of paper. All the great teas of Asia were represented: Black Sea teas, Darjeeling teas, Ceylon teas, chamomile and mint teas. The enticing smells conjured images of caravan traders along the Silk Road. Beyond the tea sacks we found an incredible selection of coffees and honey, as well as cinnamon sticks, saffron and cumin seeds. A string of sea sponges hung high on the walls, just above a shelf of Ottoman coffee mills -- large brass hand grinders that are as beautiful as they are functional. I was very interested in buying a coffee mill in order to use it as a pepper mill back home, but I saw no reason to lug it around Turkey for over two weeks when I could just buy one upon my return to Istanbul. The shop owner did his best to sweet-talk us into a purchase with more samples of honey candies, but we politely declined and returned to the chaos of the market hall.

scribbled in ink pen on a slip of paper. All the great teas of Asia were represented: Black Sea teas, Darjeeling teas, Ceylon teas, chamomile and mint teas. The enticing smells conjured images of caravan traders along the Silk Road. Beyond the tea sacks we found an incredible selection of coffees and honey, as well as cinnamon sticks, saffron and cumin seeds. A string of sea sponges hung high on the walls, just above a shelf of Ottoman coffee mills -- large brass hand grinders that are as beautiful as they are functional. I was very interested in buying a coffee mill in order to use it as a pepper mill back home, but I saw no reason to lug it around Turkey for over two weeks when I could just buy one upon my return to Istanbul. The shop owner did his best to sweet-talk us into a purchase with more samples of honey candies, but we politely declined and returned to the chaos of the market hall.

|

| A woman in a black chador sits with her family |

After having our fill of the Egyptian bazaars' innumerable aromatics, we exited the back of the building, finding ourselves in front of a fish market by the Yeni Camii Mosque. There seemed to be just as many people around the square as there had been packed inside the market, though the outside scene was much more relaxed. Old men fed pigeons as parents bought their children freshly roasted corn and sesame bagel-like rings of simit from street vendors. A group of boys played soccer with a small ball, carefully avoiding a group of men sitting on the mosque steps who chatted away as they thumbed their prayer beads. Just beyond the square a busy avenue hosted an early afternoon traffic jam, with hundreds of cars lining up to cross the Galata Bridge over the Golden Horn. Susanne and I sat briefly among the crowds, changing film while enjoying the panorama of activity. We both took some photos with our zooms lenses, hoping to capture the action going on that day.

High on a hill to the west we could see Suleymaniye Camii, the Mosque of Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent. I couldn't tell exactly how far away it was, but I suggested that we try to visit it after finding the Rüstem Pasa Mosque first. Unfortunately, finding Rüstem Pasa Camii wasn't as simple as our map suggested. Despite its fame as one of Sinan's architectural masterpieces, the 16th century mosque was hidden amongst a maze of markets, propped on the second floor of what is now a hardware and household goods bazaar. Susanne and I began our walk uphill, departing the openness of Yeni Camii Square into the claustrophobic labyrinth of hardware shops. There were no obvious signs leading to the Rüstem Pasa Mosque. Our guidebook suggested we wander the market until we found it, asking for directions if need be.

|

Anatolian Trivia

Mimar Sinan, the Ottoman Empire's most famous architect, was born to an Anatolian Greek family around 1489. Drafted by the empire as a young man, he became a member of the Ottoman equivalent of the Army Corps of Engineers. Over the course of over 25 years, Sinan demonstrated tremendous skills in designing military fortifications. Only when he was 50 years old did he begin to design non-military buildings. Despite his age, his artistry caught the attention of the Ottoman court, who soon appointed him Chief Architect. For the next 40 years, Sinan constructed such masterpieces the Mosque of Suleyman the Magnificent in Istanbul (built 1550-1557), and the Mosque of Selim II in Edirne (built circa 1570-1574). Sinan stayed active as an architect until he died around 1679, when he was approximately 90 years old.

|

Never one to reject the challenge of finding a needle in a haystack, I suggested different paths through the market, hoping my confidence would translate into dumb luck. The streets were crowded with Turks hunting for pots, pans, plumbing equipment and linoleum tiles in the housewares market. There were no spices to be found here in this particular neighborhood -- spice racks, perhaps, but no spices. Nevertheless, the persistent activities of the market were a refreshing change from Istanbul's more touristed neighborhoods.

Within ten minutes of entering the market Susanne and I spotted an open doorway leading to a steep set of stairs. A sign near the doorway identified it as cami giris, which I immediately recognized as meaning "mosque entrance." The two of us walked upstairs to find a broad marble plaza with intricate blue tiles covering the outer wall of the mosque, located just to our right. Two men quietly prayed on small rugs just in front of the tile wall, while a third man washed his hands meticulously in a decorated fountain. Towards the back of the plaza I saw another sign repeating the word "Giris," with an arrow pointing to the right. We walked around the corner and found the entrance to the mosque itself. Susanne and I removed our shoes and put them in the wooden shelves lining the wall. A small placard explained in both English and Turkish that visitors may enter if "dressed accordingly." Both Susanne and I were wearing long sleeve shirts and long pants that afternoon, but we realized that Susanne didn't have a head scarf to cover her hair. We improvised by tying an extra red shirt around Susanne's head. To our surprise the shirt didn't look ridiculous, so we figured it was now all right to enter the mosque.

Just inside the mosque we found a blind attendant with a short beard.

"Iyi günler, effendim,"

effendim," I said, greeting him.

I said, greeting him.

"Merhaba," the man replied. He then spoke in Turkish and pointed to his feet, making sure that we had removed our shoes.

"Evet, evet," I assured him. "Dert degil."

I assured him. "Dert degil."

"Tamam," he replied, inviting us inside.

he replied, inviting us inside.

The mosque itself was very small, especially when compared to the grandeur of the Blue Mosque. But despite its modest size the mosque was thoroughly impressive, lined with intricate patterns of gorgeous blue tiles around the entire hall. An Ottoman chandelier extended down from the high ceiling, hovering just out of reach around the center of the room. I didn't think there was enough light to take pictures inside, but just in case I decided to ask the attendant if it would be okay to use our cameras.

"Fotograf çekebilirmiyiz, effendim?"

effendim?" I asked.

I asked.

The attendant replied with a quick nod of his head. Turks have a unique way of gesturing yes and no: a quick nod downward means yes while a nod upward means no. (A side-to-side head movement that would normally mean "no" in America actually means "I don't understand" in Turkey.)

Just to be sure I understood his gesture I repeated the word for yes: "Evet?"

"Evet," he responded, again dipping his head down in a single motion.

"Sag olun," I replied, thanking him.

I replied, thanking him.

Susanne was now towards the far end of the mosque, where I spotted an old man praying on his knees. He was dressed in very traditional Turkish clothing, including a skullcap, vest and baggy trousers. His long gray beard nearly reached the floor while he kneeled. The photographer in me wanted to capture him on film but my conscience prevailed, unwilling to intrude on his period of devotion.

In the far left corner of the mosque I noticed a stained glass window with beams of light shining through it. Two windows down sat a small wooden stand covered in prayer beads. The stand, unfortunately, was nowhere near the beautiful light.

"How bad of a faux pas would it be for us to move the prayer bead stand into the light?" I whispered to Susanne.

"I don't know," she replied, "but they would probably think we were nuts."

"I guess we'll just have to commit it to memory, then," I sighed.

We spent a few more minutes in the mosque, admiring its tranquillity. As we exited and retrieved our shoes, I was approached by the blind attendant and a second man who must have entered the mosque as we were wandering around.

"Bahsis," they said in unison, asking me for a tip.

they said in unison, asking me for a tip.

I reached into my pocket and handed the blind attendant a 500,000 lira note, worth just over a dollar. The second man then looked at me and held out his hand. Despite the fact that this was the first time I'd even seen him, I didn't want to argue inside a mosque. I gave him a half million lira note as well, to which he bowed his head in thanks. As we left the mosque, a young woman in a chador helped her young girls take off their shoes. The woman saw us looking at her children and gave us a broad smile.

Susanne and I walked uphill beyond the hardware market towards the Suleymaniye Mosque. We climbed the steep thoroughfare slowly, hoping not to overheat under the mid-afternoon sun. In 15 minutes we reached the high stone walls of the mosque, though neither of us knew where the main entrance was. We walked clockwise around the walls until we reached a darkened gate full of stone rubble. I paused for a moment, trying to determine if this was a proper entrance to the mosque or an abandoned gate. Concluding it wasn't the best way to get inside, we began to continue our walk. A group of Turkish men strolling down the street saw us departing the gate. One of them asked us in English, "Where are you going?"

"Suleymaniye camii nerede?," I replied, struggling in Turkish. "Bunu giris, degil mi?"

"Yes, this is the gate to the Suleymaniye Mosque," the man said in English, smiling at my attempt. "You can enter right here."

"Tesekkür ederim,"

"Bahsis," I responded.

I responded.

"My pleasure," he replied. "Güle güle!"

Susanne and I weaved up the stone passageway and soon found ourselves atop the northeast corner of the mosque's gardens. To our right, a long marble wall stood guard over Istanbul, offering us a tremendous view of the Golden Horn and modern Istanbul. Far to the right across the Bosphorus, we could make out Asian Istanbul, the gateway to the Anatolian plateau. Two women in headscarves picnicked along the edge of wall while a young boy played with his new toy truck, rolling it along the marble platform.

|

| Suleymaniye Mosque, Istanbul |

We walked straight into the gardens, with the massive Suleymaniye Mosque dominating the view to the left. The largest mosque built in the Ottoman Empire, Suleymaniye Camii was constructed by Sinan from 1550 to 1557 as a mausoleum for his patron, Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent. We strolled counterclockwise around the mosque, looking for its main entrance. A large Turkish family armed with a video camera strolled through the gardens as a young boy in a curious white costume paraded in front of them. He was dressed in a white suit trimmed in gold cloth, a tall feathered hat on his head and a royal scepter in his hand. We immediately recognized the purpose of their visit -- the boy was on his way to his circumcision, an auspicious celebration of entering manhood not unlike a Bar Mitzvah. The whole family had gathered for the event; once it was complete, the boy would rest in bed while the family entertained him with music, dancing and feasting. We were tempted to get a closeup photo of him but the family seemed to be leaving, so we figured we might try to ask for a photo from the next boy we found on his circumcisional march.

We eventually reached the mosque's entrance and walked inside after removing our shoes. The mosque was massive, much bigger than the Blue Mosque. In some ways I felt somewhat intimidated by its size. Suleyman the Magnificent, the most celebrated of Ottoman Sultans, had his mosque built on scale never seen before in the Islamic world and rarely seen since. Susanne and I quietly wandered the interior, observing a small group of men praying under the center of the chandelier.

As we stepped outside and put on our shoes, I spoke softly to Susanne. "It's a beautiful mosque," I said, "but I wonder if we'll soon reach the point of being 'mosqued out,' kind of like after seeing too many cathedrals in Europe or too many Buddhist wats in Thailand."

"I know what you mean," Susanne replied. "After a while you begin to lose perspective."

"I suppose after today we won't see too many mosques for a while, since we're on our way to Roman and Byzantine sites. I would just hate to get burnt out on them so early on in the trip."

It was now past 3pm, so Susanne and I returned to the hotel by way of a flea market behind the Kapali Çarsi. We still needed to pick up our airline tickets for Izmir and Van, so Susanne settled upstairs on the hotel's rooftop terrace while I ran around the corner to the travel agency. As I exited the hotel I saw an Asian woman from Australia feasting on the largest peach I've ever seen. "An early dinner," she said as she saw me gawking at her gargantuan fruit.

I made a quick stop at the travel agency and retrieved our tickets before returning to the hotel terrace, where I found Susanne settled down over her journal. I suggested we visit the rooftop itself, which appeared to be unlocked. Upstairs we found an incredible view of Aya Sofya, perched just beyond the hotel about two blocks away. We spent a few minutes taking pictures of the church just as the late afternoon call to prayer began. A muezzin sang from the direction of the Blue Mosque, several blocks to the west. A moment or two later a second muezzin could be heard from another mosque behind the hotel. Then a third, a four, a fifth. The air was filled with pious voices in all directions. Susanne and I looked at each other and smiled.

sang from the direction of the Blue Mosque, several blocks to the west. A moment or two later a second muezzin could be heard from another mosque behind the hotel. Then a third, a four, a fifth. The air was filled with pious voices in all directions. Susanne and I looked at each other and smiled.

"This is why I came here," I said.

"I know," she replied. "Me too."

|

| Aya Sofya (Hagia Sophia) |

We listened to the muezzins for several minutes. I glanced across the street to the Four Seasons Hotel, where a group of employees were setting up for a party on the rooftop. On the street below, two hotel doormen were messing around, demonstrating wrestling moves on each other. I was fascinated by the dichotomy of the scene before me: two men wrestling as the calls to prayer filled our ears. It was Istanbul in miniature, a collision of two worlds, old and new, religious and secular, somehow mingling together in relative harmony.

Back downstairs, Susanne and I made a phone call to Aydin, who had tried to reach us the night before back at the Orient Hostel. Aydin suggested we get together at nine o'clock at the Marmara Hotel Cafe, at the heart of modern Istanbul in Taksim Square. This gave us plenty of time to relax over dinner. Unfortunately, finding a dinner we could agree upon wasn't as easy as it should have been that night. While I was interested in getting a hearty Turkish kebap, Susanne wanted to play it more cautious and get pizza or some other benign meal. We struggled for some time trying to find a restaurant that was acceptable to both of us. Perhaps our long day had caught up with us, for we were growing more impatient with each rejected menu.

Finally we agreed up the Sultan Pub, a popular restaurant and bar with western meals and Turkish dishes toned down for foreign tastes. I selected a spicy Iskender kebap and a pint of Efes Pilsner while Susanne settled on a vegetarian pizza and a Sprite, while we both snacked on an order of yesil zeytin ve fistek (green olives and pistachios). We talked for a while with an American couple from Tennessee who was in Istanbul for several days before embarking on a Mediterranean cruise. During our conversation, the couple noted they had yet to notice the muezzins singing their calls to prayer. We feasted on our meals through sunset, during which the other couple finally got their chance to hear their first call to prayer. After dinner I was a little surprised by the bill of eight million lira (about $18). While the total in itself wasn't much by American standards, I found the eight dollars charged for the diminutive bowls of olives and pistachios to be rather extortionist.

and a pint of Efes Pilsner while Susanne settled on a vegetarian pizza and a Sprite, while we both snacked on an order of yesil zeytin ve fistek (green olives and pistachios). We talked for a while with an American couple from Tennessee who was in Istanbul for several days before embarking on a Mediterranean cruise. During our conversation, the couple noted they had yet to notice the muezzins singing their calls to prayer. We feasted on our meals through sunset, during which the other couple finally got their chance to hear their first call to prayer. After dinner I was a little surprised by the bill of eight million lira (about $18). While the total in itself wasn't much by American standards, I found the eight dollars charged for the diminutive bowls of olives and pistachios to be rather extortionist.

Just after 8:30pm we hailed a cab from behind the Four Seasons and drove over the Golden Horn into Taksim Square. Taksim Square is the pulse of the new Istanbul, a bustling plaza of lavish hotels, trendy cafes and countless strolling couples holding hands. The Marmara Hotel Cafe was an upscale bakery and restaurant where Turks and tourists alike stuffed themselves with cream pies and banana splits. Susanne and I sat for 30 minutes before ordering anything, waiting under the assumption that Aydin could arrive at any minute. Eventually my thirst got the best of me so I ordered a lemonade. A few minutes later the waiter brought out a bottle of mineral water. I figured the water was at least lemon flavored but upon tasting it realized he had brought me the wrong drink. Meanwhile, Susanne and I joked over how we would spot Aydin when he arrived. We had no idea what he looked like, so every man over 18 and under 80 was given our full scrutiny.

Around 10pm a young man with longish brown hair walked in the cafe, a beautiful Turkish woman by his side. He was perhaps around 30 years old and was sporting a Chicago Field Museum "Sue the Dinosaur" t-shirt. He quickly noticed that Susanne and I were scoping him out, so he gave us a broad smile and asked, "Andy?"

"Aydin?" I replied.

"Good to meet you finally!" he said, grinning while giving me a firm handshake.

The four of us settled down at our table and ordered a round of drinks. We spent much of the first hour talking about Aydin's life as a tour guide and his work with National Geographic groups. All of his recent tours with them had been far to the west of our primary destination, eastern Anatolia and Kurdistan. "There you'll get to see the real Turkey, where the tourists never go," he said. "You will love it, I promise."

By 11pm we finally got down to the main purpose of our gathering -- sorting out the logistics of the rest of our trip. "Tell me everywhere you want to go and how long you want to go there," Aydin explained, "and I will tell you how to do it."

Our first stop, Ephesus, would require us to fly down to Izmir and before continuing to the town of Selçuk, just over an hour south. "Don't take the bus from the airport to the Izmir otogar," Aydin explained. "Even though all the Selçuk buses run from the otogar, it's is far to the north in the wrong direction. Instead you should be able to catch a dolmus

Aydin explained. "Even though all the Selçuk buses run from the otogar, it's is far to the north in the wrong direction. Instead you should be able to catch a dolmus from just beyond the airport."

from just beyond the airport."

"You should also stay at the Hotel Kalehan in Selçuk," he said. "I know the owner well -- he comes from an old Ottoman family. He built the hotel all himself, and it is very nice. I will call him and make sure you get a room for a good price." I had originally wanted to spend two nights in Selçuk but we all agreed that one night would be enough to see the ruins of Ephesus, thus saving an extra day for later on in the trip.

From Selçuk we would have to catch an overnight bus to Cappadokia, where we planned to spend two full days. "You should have no problem catching a bus to Cappadokia," Aydin said. "Just be sure to take a good bus company like Varan, because you don't want a poorly paid driver to fall asleep at the wheel. It happens, you know." Aydin suggested that we take a tour in Cappadokia to get a feel for the area and cover sites further afield, while spending a second day exploring on our own.

"If you have the money," he continued, "you should take a balloon ride over Cappadokia. It is absolutely amazing." For just over $200 each we could take a 90-minute ride over the Cappadokian valleys, where the balloonsman would literally bring us down to pick apricots right of the orchard trees. It was a tempting idea, but we'd just have to see how our money was holding up at that point.

From Cappadokia we would then have to find our way to the grimy oil town of Kahta in order to make an early morning ascent to the mountaintop ruins of Nemrut Dagi. "It's a long trip to get there but it's well worth it," Aydin said. In order to get there we would have to change buses at least three times over a very long day, or we could join a private tour for $100 and up. Susanne and I both preferred to avoid tours in general but we thought that it might be worth it just for the sake of time and convenience. We'd make our decision once we were in Cappadokia. From Nemrut Dagi, we hoped to visit the town of Urfa, three hours to the south. "Not a problem," Aydin insisted. "There are plenty of buses going there."

The rest of our trip would focus on the heart of Turkish Kurdistan, far out in southeastern Anatolia. The city of Van seemed like the best base of operations but it would take a 10-hour bus ride to get there from Urfa. "You'll have to do it in the daytime," Aydin warned. "There are no overnight buses to Van -- it is too dangerous. You'll just have to plan a day for bus travel."

Aydin suggested we spend three days around Van -- one day exploring the city and its ancient castle, another day visiting the Kurdish castle of Hosap and the Armenian church on Akdamar Island, and a third day making a long daytrip to Ishak Pasa's Palace near Dogubeyazit, below the slopes of Mount Ararat. Considering there was absolutely no capacity for organized tourism in Kurdistan, we wondered how difficult it would be to cover all of those places in three days. We'd have to play it by ear.

After flying back from Van, we would have three nights in Istanbul to relax and re-visit our favorite sights. Aydin strongly suggested we enjoy a Turkish bath at the Çemberlitas Hamam, a 16th century bath house built by the great architect Sinan. "Don't go to a hamam until the end of the trip," Aydin insisted. "You will only enjoy it even more if you wait." He also suggested we visit a nargileh garden just west of the hamam, where old men drank tea and smoked water pipes all day. It sounded like the perfect place to wrap up our Turkish journey.

Just after midnight Aydin kindly offered to drive us back to the Ottoman Guesthouse in a friend's Alfa Romeo he was borrowing. The ride over the Galata Bridge offered a tremendous view of Istanbul at night, with the illuminated Aya Sofya and Suleyman's Mosque standing guard over Sultanahmet. I wanted to drive around all night, marveling at the spectacle of Istanbul all aglow, but our long day had finally caught up with me. Tomorrow we would begin our Anatolian adventure, and now it was time to rest.

last night

last night  so I paid for the first night and returned to the Orient to tell Susanne of our impending move.

so I paid for the first night and returned to the Orient to tell Susanne of our impending move. a small mosque known for its intricate blue tilework, for which we had search in vain the previous day. We both knew it was an ambitious itinerary for one day, but Susanne and I felt confident we could do them justice without killing ourselves in the process.

a small mosque known for its intricate blue tilework, for which we had search in vain the previous day. We both knew it was an ambitious itinerary for one day, but Susanne and I felt confident we could do them justice without killing ourselves in the process.