|

| Church of St. Gregory, Ani |

Tuesday, September 7.

After waking up at 7am, Susanne and I went downstairs to the hotel dining room for breakfast. A Turkish breakfast buffet had been set up near the bar, including fresh bread, green and black olives, goat cheese, hard boiled eggs and honey. Susanne and I both took our plates outside to the terrace, where a waiter brought out hot cups of Nescafe with milk.

As we finished breakfast, Berzan's Van cat appeared from inside. Susanne and I both made a feeble attempt to pick it up, but the frisky kitten was too quick for us. The waiter returned to retrieve our plates when he saw our dilemma. He obligingly reached down and lifted the cat, holding it on the table for us to take a picture. Unfortunately the cat didn't look too happy to be tethered by the waiter's grasp, but it humored us for a moment and allowed us to get that photograph.

We met Berzan with our bags just after 7:30. Once again I bought a large bottle of water for the ride up to Kars, which would take "four or five hours depending on the number of police checkpoints," as Berzan put it. His words really struck me -- it was one thing for weather or traffic to be the variable affecting your travel plans. Potential police harassment was a new issue for consideration. New for us, perhaps, but a daily way of life for our Kurdish guide.

Reaching Van's northern city limits around 8 o'clock we stopped for our first checkpoint. As had been the case going south, we were scrutinized by a plain-clothes official in a dark vest. After examining our IDs the official asked Berzan to unlock the trunk for inspection. Once on our way again we followed the highway north. Over 1000 years ago this very road was a major Silk Road artery connecting the cities of Persia with the Armenian capital of Ani to the north and the Roman town of Caesaria (modern Kayseri) far to the west in Cappadokia. Today the highway is still called Ipek Yolu, or Silk Road.

Soon after leaving Lake Van behind us we were stopped at a military checkpoint. A sour-faced jendarma approached Berzan's window and took our identification. Berzan was then asked to step out of the car to open the trunk. A moment or two later the jendarma knocked on the window to my left. I rolled down the window to find out what was going on just as the jendarma began to speak swiftly in Turkish.

approached Berzan's window and took our identification. Berzan was then asked to step out of the car to open the trunk. A moment or two later the jendarma knocked on the window to my left. I rolled down the window to find out what was going on just as the jendarma began to speak swiftly in Turkish.

An exasperated Berzan approached the window. "He wants both of you to get out and open up your luggage," he said.

Susanne and I both stepped out of the car and walked back to the trunk. I opened my bag first, displaying a motley collection of dirty old shirts and unspeakably crusty socks. Satisfied that I wasn't carrying a bomb or copies of the US Constitution in Kurdish, he moved on to Susanne's bag, which had been closed with a small padlock. Again, the jendarma found nothing that could alter the balance in the Turkish-Kurdish conflict.

"You can get back in the car now," Berzan said as the jendarma closed Susanne's bag.

We sat in the car for a moment until Berzan returned, starting up the car and cranking up his Kurdish music as soon as we were no longer in earshot.

"I hate them for that," he said quite clearly in English.

"I can't imagine having to live like this," Susanne sighed.

"They're killing us," Berzan said, shaking his head.

We drove northward for an hour through typical farm country, an occasional mountain looming in the distance. As the number of hills began to increase I noticed the ground was now littered with cracked black boulders, sometimes so prevalent it was as the earth had disemboweled itself. We were in an ancient lava field, which meant that Anatolia's most famous dormant volcano was not far away -- we were approaching Mount Ararat, the legendary resting place of Noah's Ark.

A few miles further into the lava field we stopped briefly at another jendarma checkpoint. As we left the checkpoint I could see military barracks surrounded by barbed wire extending far to the east. Along the barbed wire was an ominous red sign with a black outline of a rifle-toting soldier. "Dikkat!" it read. "Attention! Forbidden Zone!" Mount Ararat was perilously close to Turkey's borders with Armenia and Iran, making it a prime spot for heroin smuggling, illegal Kurdish immigrants, even arms trafficking. Mounting an expedition up the slopes of Ararat was near impossible without friends in high places (no pun intended), and permits to climb the mountain are routinely rejected. Mount Ararat, the place where Noah's journey came to a safe end, is now one of the least safe places in the Middle East as far as the Turkish army is concerned.

As we weaved through the lava field my eyes continued to follow the barbed wire fences and the many red and black Forbidden Zone signs that decorated them. Suddenly, seemingly out of nowhere, Mount Ararat appeared in the east, dominating our entire field of view. Often obscured by clouds, Ararat was today clear and crisp, its dark gray slopes capped with an icy white layer of eternal snow.

|

| Mount Ararat, Turkish Kurdistan |

"Can we pull over for a photo?" Susanne and I exclaimed almost simultaneously.

"Not yet," Berzan replied. "The army can see us here."

Several minutes later, after our car had curved around a hillside, Berzan pulled over to the left of the highway, parking in the midst of the lava field. Ever the science geek at heart I immediately reached for a piece of foamy black lava as I stepped out of the car. "Look how light this lava is," I said to Susanne. "It's like black pumice or something...."

"Please," Berzan stressed, "we cannot stay here long. Please take your picture. I had trouble last year...."

Not wanting to get anyone in trouble, Susanne and I quickly crossed the road to take our pictures of Mount Ararat. As we snapped our photos a young girl appeared from the village to see what we were doing. Berzan soon relaxed with her presence, even asking us to take a picture of them together.

"Isminizne?" I asked her.

I asked her.

"Dim," she replied.

Before I could introduce myself, Berzan ushered us back into the car. "We really must go now," he said, starting the ignition as I closed my door.

I had trouble last year.... I thought of Berzan's words as we drove northward. I did not want to venture whether that was an understatement.

With Ararat still dominating our view to the east, we soon arrived in Dogubeyazit, a dusty frontier town known for its border crossing with Iran and its famed Kurdish palace of Ishak Pasa. We planned to visit the palace tomorrow, so for now Dogubeyazit was nothing more than another windswept spot along the highway.

"Would you like to stop for some tea?" Berzan asked.

"Sure," Susanne and I replied. I expected us to pull over in Dogubeyazit but Berzan drove on to the next major town, Igdir.

"What is this town called again?" Susanne asked as we reached Igdir's city limits.

"Uch-dursh," Berzan said with a deep gutteral voice, sounding almost like he was mumbling in German.

|

Turkish Pronunciation

Interested in learning how to pronounce the Turkish words mentioned in this journal? Check out my Turkish pronunication guide!

|

I knew that the Turkish G was usually silent and the letter I without a dot over it was pronounced in between the sounds "ih" and "uh." I also knew that some Turks put a "sh" sound when the letter R is at the end of a word (like pronouncing the city Izmir as Izmirsh). But apart from Berzan I hadn't encountered the hard ch sound in Turkish.

"I would have guessed this town would be pronounced Uhh-duhrsh," I commented, "but you pronounce it like Uch-duhrsh. Is the ch sound a Kurdish trait?"

"Yes, we use a lot of hard ch's," Berzan replied. "Uch Duhrsh, Dochubeyazit. It sounds much better that way."

Igdir is a medium-size university town with not much to note except that it makes a convenient place to stop for tea after being on the Van-Kars highway for a few hours. We parked along a busy street next to an otogar and a produce market. Just across the street we found a hole-in-the-wall tea shack with two small tables and several squat stools out in front. As the three of us were settling in around a table, Susanne said she needed to find a bathroom. Since the tea joint had no room for a kitchen let alone a bathroom, Berzan offered to walk Susanne over to the otogar while I waited at the table.

Susanne and Berzan disappeared in the crowd across the street. Meanwhile I quickly discovered that the empty seat and table I was guarding was a precious commodity here in Igdir. Two old men approached the cafe and grabbed on to Susanne's and Berzan's chairs. Wanting to make clear to them that these chairs were spoken for by my friends, I did my best to convey my apologies in Turkish.

"Üzgünüm, effendim -- benim arkadaslar," I said to them. Excuse me, sirs -- my friends. I couldn't get more specific than that because my Turkish skills were so limited, but I hoped I at least got my point across.

"Arkadaslar?" one of the men responded rather skeptically, as if I had just introduced them to a pair of imaginary friends.

one of the men responded rather skeptically, as if I had just introduced them to a pair of imaginary friends.

"Nerede?" the other one challenged me. Where?

"Tuvalet," I replied, realizing that they didn't find my chair-hogging excuse very convincing.

I replied, realizing that they didn't find my chair-hogging excuse very convincing.

"Tuvalet!" he exclaimed, throwing his hand up in the air before leaving me to the company of my troubled imagination.

Berzan and Susanne soon reappeared from across the street.

"Where's my tea?" Berzan asked sarcastically.

"Don't blame me," I said. "Blame your two empty chairs, which almost didn't stay empty for long."

We eventually received a round of tea, while snacking on some chocolate biscuits. "We are almost there," Berzan assured us. "Two hours at most."

After paying the waiter we returned to the main road to Kars. Much of the drive for the next hour was perilously close to Armenian territory -- often no further than a kilometer or two. That made all land to the east of the road strictly off limits -- razor wire and numerous "Forbidden Zone" signs would greet every glance I made out the right-side window.

Our drive was slowed significantly by what seemed to be an infinite stream of lumbering military transports. We found ourselves behind two army border patrol convoys, each made up of 20 or so vehicles. At first I assumed we'd be stuck behind them for the rest of the ride, but Berzan wasted no time in speeding down the left lane, veering into the convoy to avoid oncoming traffic. We weaved in and out, in and out, usually encountering blank stares from the heavily armed 20-year-olds stacked in the back of each truck. The vast majority of them looked terminally bored, counting down the days, hours and minutes left in their 18-month conscription. Occasionally I spotted a handful of soldiers joking around or perhaps bobbing their heads up and down to the sound of their Walkmans. One transport's complement was completely asleep, flopped on each other's shoulders like a litter of newborn kittens.

After snaking through multiple lava fields we neared an area of rolling farmland that marked our approach to the city of Kars. Acres of land were pockmarked by evenly-spaced piles of rocks, as if the farmers had just harvested their annual gravel crop. For a brief, grim moment I thought the stones were actually thousands of markers for the graves of soldiers killed fighting the Kurds, so I decided to ask Berzan what they were for.

"The land here has good soil but there are too many rocks in the fields," he explained. "Since the farmers have no place to put the rocks they put them into small piles so can farm the land around them."

Not far after the rocky fields we reached the outer limits of Kars. Small apartment blocks and auto repair shops lined the sides of the road. Lonely Planet had warned us that Kars had nothing to offer except an excursion point for the ruins of Ani, but as we entered town I was pleasantly surprised by its setting. Tree-lined streets, turn-of-the-century Russian houses that smelled of wet paint, public fountains, and freshly paved roads: Kars was obviously in the middle of a face lift.

The Russians built Kars in the late 1800s on a strict grid plan giving it a very European feel, but the city's location on the westernmost edge of the Caucasus makes you feel as if you've just arrived in Yerevan or Tiblisi. Many of the storefronts carried signs that appear to display the name Kafka's but I quickly realized that the word in fact was Kafkas, based on the Russian word for the Caucasus mountains, Kavkaz.

"Kars still likes to look to the East," Berzan said. "Many of the residents are Azeri Turks who settled here while the Russians were in Kars."

Russia's foray into Kars lasted less than 40 years; the Turks regained the city near the end of World War I, during the spring of 1918. But recapturing the city had come at an enormous cost, including what was one of the most self-destructive campaigns of the entire war. In December 1915, Ottoman military generalissimo Enver Pasha sent the Turkish Third Army towards the Russian-occupied Caucasus, in the hopes of liberating the region as a first step towards establishing a pan-Turkic empire across Central Asia.

Though northeastern Anatolia is known for its difficult winters (Kars literally means "snow" in Turkish), the winter of 1915 was particularly brutal. The commander of the Third Army, a former military college instructor of Enver's, begged the pasha to not force him to attack the Russians before the winter subsided. Enver, who had never commanded a regiment, relieved his former teacher of his duties and took over the Third Army, renaming it the Army of Islam. Enver pressed over 90,000 troops from Erzerum towards Kars, reportedly forcing his men to leave behind rations and precious layers of clothing in order to speed up the march.

|

Anatolian Trivia

Not far from Sarikamis, another decisive battle took place along the northern shores of Lake Van in 1071. At the Battle of Manzikert, Byzantine emperor Romanus Diogenes was humiliated by the forces of the Seljuk Turks, led by Sultan Alp Arslan. Captured by the Seljuks and forced to pay annual tribute, Romanus had lost the battle in part because of treacherous Byzantine rivals who may have encouraged their troops to retreat prematurely. Manzikert served as a stark demonstration of the ascension of the Turks in Anatolia - and prophesied the eventual fall of the Byzantines, who lost Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453.

|

By Christmas 1915, the Army of Islam arrived at the outskirts of Sarikamis, a small Russian garrison town just west of Kars. Enver planned to capture Sarikamis as the first step in liberating the Caucasus, but the frigid weather had devastated his Army of Islam -- thousands of men froze to death on their way to Sarikamis. Enver ordered his desperately weakened soldiers to attack Sarikamis on December 29, but it was a lost cause. By the time Enver retreated and returned to Constantinople, 75,000 soldiers of the Army of Islam had died, leaving barely 15,000 survivors.

Enver did his best to cover up his ineptitude, but the crushing defeat severely limited the Ottoman threat to the Russians in the Caucasus mountains. To the Russians, though, Enver's attack was a dangerous diversion from their primary front against the Germans in Eastern Europe, which was not going well to begin with. Because of Enver's attack, the Russians lobbied the British to start another front against the Turks. After extended debate led by then-Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill, the British agreed to accept the challenge, laying the seeds for what would eventually be their disastrous invasion along the Gallipoli peninsula. Ironically, the Turkish victory at Gallipoli propelled a young soldier named Mustafa Kemal to fame, who had rallied the Ottoman troops at a decisive moment. In less than ten years, Kemal would become the founder of the modern Turkish republic and be forever remembered as Father Turk -- Atatürk.

Near the center of town, Berzan pulled over to the state tourism office in order to begin the process of receiving permission to enter the ruins of Ani. Because Ani is so close to the Armenian border, the Turks have piled up the red tape in order to scrutinize everyone who wants to visit it -- and perhaps to discourage others from even bothering. After stepping inside the office armed with our passports, Berzan returned and started up the car.

"We must go to another office first then come back here," he said. "They have changed the rules since I was here last."

A few blocks away we arrived at what appeared to be the center of town -- a T-shaped intersection with a large public fountain and numerous park benches. There was nowhere to park so Berzan manouvered the car right up to the fountain and turned on his blinkers.

"I will only be a minute," he said, taking our passports once again. "If the police come to take away the car tell them I will be back soon."

Susanne and I looked at each other as Berzan walked into the building.

"The police aren't going to like this," Susanne said.

"That's okay," I replied. "I can point to the empty driver's seat and say in Turkish, 'Arkadas! Arkadas!' like I did in Igdir."

We didn't spot any police during our wait but we soon lost count of the number of teenagers we saw walking down the street. Boys and girls in blue jeans, t-shirts and baseball caps strolled around the fountain plaza, probably on the way to lunch from the nearby high school and university campus. While some older women wore head scarves, none of the younger women did. I also noticed that a surprising number of the men were redheads -- not brunettes with a hint of crimson, but fiery Irish redheads. I cracked the window to get some fresh air and was greeted by a cool breeze -- Kars was indeed mild compared with Van and southeastern Turkey.

Berzan soon returned with our passports and a brown sheet of paper. "Okay, now we can go back to the other office." He turned the car around and brought us back to the first building we had visited just 15 minutes earlier. Once again, Berzan ran inside, though this time he exited with just what we needed: security approval stamps on our entry form.

"There is still one more stop," Berzan said. "We will need to buy entry tickets since they are not available at Ani. But first we can go to the hotel and get some lunch."

We drove around the corner and parked in front of the Hotel Güngören, a dilapidated two-star which at one time in the past may have been charming. As we checked in, the man behind the desk and Berzan had an extended conversation in Turkish. From what I could make out they were arguing over whether to give Susanne and me a double bed or a single bed (a "French bed," they called it.) Eventually they grew tired of their debate and settled on giving us an extra-large triple.

Once inside the room we discovered stiff beds, a stiff sofa, stiff chairs, stiff lighting and a fluttering color TV.

"How Soviet," Susanne said.

"It's like the Russians never left Kars," I replied.

On the desk I found a Kars Turism folder that contained a postcard of the city taken at night. "What does it tell you when the only postcard they can give you is a picture of the city in the dark?" Susanne quipped.

We met Berzan at the front desk and drove a few blocks away to a döner kebapci.

kebapci. We sat on a long picnic bench right across from a produce market which offered large watermelons and even larger cabbages. A teenaged waiter brought us bottles of Coke and slices of fresh pide

We sat on a long picnic bench right across from a produce market which offered large watermelons and even larger cabbages. A teenaged waiter brought us bottles of Coke and slices of fresh pide as a chef who looked like Monty Python's Graham Chapman shaved slices of meat off a flamethrowing rotisserie. As a döner kebapci, the restaurant didn't have much to offer but döner kebaps

as a chef who looked like Monty Python's Graham Chapman shaved slices of meat off a flamethrowing rotisserie. As a döner kebapci, the restaurant didn't have much to offer but döner kebaps and drinks -- our choices were limited.

and drinks -- our choices were limited.

We soon received our kebaps piled over a mound of greasy rice. I had expected the döner to taste more like Greek gyros since the concepts are almost identical, but the döner meat was marbled and chewy, more like a slice of unprocessed lamb. The meat was rather oily as well, which made the kebap a little undesirable but left the rice with a delicious gravy. Susanne proceeded to hide her uneaten meat under her rice. I almost inadvertently revealed her deception when I greedily scooped a spoonful of rice from her plate, but Berzan seemed neither to care nor to notice.

After lunch we made our final bureaucracy stop at the Kars Archeology Museum, where Berzan was able to procure our Ani entry tickets after proving we had permission to visit the site. We then began the 30-minute drive to Ani, across the train tracks and through several poor farming villages. Somewhere in front of us was Ani, and just beyond that was Armenia. I looked at the hills and mountains ahead, trying to guess where Turkey ended and Armenia commenced. Surely the mountains were in Armenia, so I theorized that Ani would lie amongst the many hills that were visible below the mountains.

Arriving at a military checkpoint we were approached by a soldier who demanded our passports and entry permits. Carefully obeying protocol he determined that the names on the permits were indeed spelled like the names in our passports. After giving me a glance that seemed to suggest "maybe I'll not let you in just for the fun of it," he returned our passports and waved us through.

"There is a story by Nasreddin Hodja I think of sometimes," Berzan said cryptically as we left the checkpoint. "I must tell you the story later...."

Descending over the far side of a hill we could now see the outer wall of Ani. From our distant perspective it appeared that Ani was now a massive pasture with walls on one side and hills on the other side. In the middle, just out of view, must be the Ahuryan River, which serves as the natural border between Turkey and Armenia. This meant the hills that lay just beyond the walls were in Armenian territory.

After parking along a recently restored wall, we walked around the corner to a sentry post where two armed soldiers stood guard. One soldier took our passports as collateral during our visit while the other laid down the law concering Ani's tourist policy.

"This is the natural international border between Turkey and Armenia," he said in rehearsed English. "Our governments have made strict rules of conduct for your visit. You may take pictures of the ruins but you may not take pictures of the ruins facing into Armenia. You must direct your photos west towards Turkey, not east towards Armenia, or your film and camera will be confiscated. Please follow the main path around the ruins and do not step off of the path. Do not go any further south than the mosque ruins, near the citadel. Do not go to the citadel. It is not safe. If you understand these rules you may proceed."

"We understand," the three of us replied. The soldier nodded his head and slung his rifle over his shoulder in order to open the gate for us.

Once we were no longer in earshot, Berzan added, "You may only take pictures of me. Facing south. Do you understand?"

"We understand," I droned back, knowing full well we'd do what we could to get the best photographs. "I will not start an international incident with my camera."

Susanne and I were both rather incredulous about these Soviet-era rules, finding it a little absurd that we would be restricted in taking pictures of a city that died over 600 years ago. But because the Turks were still irate over Armenia's military successes against the Azerbaijanis in Nagorno-Karabakh, the border was sealed completely shut. If politics and hatred hadn't closed the border, we could have had lunch in Yerevan.

Long before the arrival of the Armenians, Turks or Kurds, eastern Anatolia was populated by the Urartu civilization. Among their many gods the Urartu worshipped Anahid, an early Persian version of Greek Aphrodite. Anahid's spell must have been truly seductive, for though her worshippers are long gone, her presence is still preserved in the name of the ancient city of Ani.

Since ancient times, eastern Turkey has been an important strategic crossroads. The legendary Silk Road passed through the region, linking the cities of Byzantine Anatolia with Persia, Arabia and Central Asia. By the late ninth century AD these crossroads were controlled by an Armenian dynasty known as the Bagratids. Recognized by both the Byzantine emperor in Constantinople and the Arab caliph in Baghdad, the Bagratids presided over prosperous principality centered around their capital city, Kars. Yet the nearby town of Ani became a tempting alternative to Kars, for it could be defended more easily given its location along a deep river gorge. In 961 AD Armenian king Ashod III the Merciful left Kars and moved his Bagratid capital to Ani, laying the foundation of what would become a glorious, yet short-lived, medieval metropolis.

By the end of the first millennium, Ani was a thriving commercial and religious center, its 100,000+ population rivaling that of Constantinople. Contemporary chroniclers boasted of the Armenian capital as "The City of a Thousand Churches." Following Ashod III, his royal successors Smbat II and Gagik I maintained Armenia's dominance in the region. But after the death of Gagik, the throne was weakened by internal rivalries, eventually allowing Byzantine emperor Constantine IX Monomachus to inherit the city in 1045 AD from Bagratid King Yovhannes-Smbat. Constantine's grasp was fleeting, however. The Seljuk Turks fighting under warrior chief Alp Arslan swept into eastern Anatolia, taking Ani and Kars in 1064 as they headed west to find fame and glory in central Turkey. They too didn't stay for long, and successive waves of Kurds and Georgians made their presence felt in Ani.

Turks fighting under warrior chief Alp Arslan swept into eastern Anatolia, taking Ani and Kars in 1064 as they headed west to find fame and glory in central Turkey. They too didn't stay for long, and successive waves of Kurds and Georgians made their presence felt in Ani.

By 1239, no power in either Europe or Asia could compete with Cingiz Khan and the Mongols, who ravaged Anatolia and captured the city. This marked the beginning of the end of Ani. Earthquakes, plagues and changing patterns in trade ravaged the local economy. The great Turkic warrior Timur Leng (Tamerlane) took Ani in the late 14th century, but soon abandoned it to Ani's dwindling Armenian population. The Armenian Catholic Church, which had been based in Ani since 992, transferred its central administration to the city of Yerevan in 1441. By the end of the 15th century, Ani was a ghost town in-progress.

And so it has been ever since. A victim of perpetual enmity between Turks and Armenians, Ani exists in a no-mans-land forgotten by history.

As we passed through the soaring stone gates we found ourselves at the edge of a rolling wheat field. All was silent except for the wind and the rubble crunching under our feet. Several hundred meters in front of us, crumbling stone churches and mosques could be seen scattered across the plain, separated by acres of wheat and shards of broken marble, never piled more than a foot or two high. It was more like a movie lot than an ancient capital: a building here, a building there, separated by ample distance to avoid film crews getting in each other's shot.

|

| The deserted Armenian ruins of Ani, along the Turkish-Armenian border |

The ruins were almost completely deserted. Several Turkish archeologists could be seen sifting through a mass of rubble, while two rifle-toting soldiers stood guard over the gorge. As we walked towards the ruins a small convoy of jeeps passed us. I could see well-dressed civilians and high ranking officers in one jeep, with nervous soldiers in another jeep. It seemed that some VIPs wanted a private tour of the ruins. This might complicate our plan to sneak pictures of the ruins facing into Armenia, I realized as I saw several of the soldiers in the jeep get out to stand guard while the VIPs explored each site. We'd have to be cautious.

|

| Lightning-shattered Church of the Redeemer, Ani |

We followed the path clockwise around the ruins, walking half a kilometer towards the Church of the Redeemer. Approaching the church from the north it appeared the structure was still in fine condition, a typical medieval Armenian church not unlike Akdamar Island's Church of the Holy Cross. But as we walked around the church we saw an entirely different picture -- the eastern half of the structure had been sheared off completely. Built in the 1030's, the church had survived intact for over 900 years until a lightning strike devastated the building in 1957.

Susanne and I climbed over mounds of rubble in front of the church in order to get high enough for a photograph. With each step I could hear the same gravel crunch that I had heard as we first entered the ruins. I kneeled to the ground and ran my fingers through the rubble. With each handful of dirt I found sizable shards of pottery, many pieces several inches wide. Everywhere you looked were mounds of medieval trash, left in situ for some future archeologist to piece together. Tempted as I was to explore the mounds, they were unstable and plagued with thorns, so I eventually took my pictures and returned to flat earth.

Walking around to the other side of the church I got a good look at the lightning damage. An entire half of the building had collapsed straight down, leaving the other half unscathed. Susanne was climbing inside the church on a large pile of marble. I scrambled over the outer ruins, shifting my gaze between the fading frescoes along the remaining vaults and the shattered walls beneath my feet. Berzan stood further back on another pile of stone, his dark sunglasses reflecting flashes of light along the shadowy interior of the church.

The three of us continued our walk down the path, which now sloped downhill towards the gorge. It was at this moment we had our first clear view of the gorge and the Ahuryan River. Cliffs on both sides of the border plunged towards the bottom of the ravine, 500 feet downward. The Ahuryan was a tumult of white water, crashing against the many boulders that had fallen down the gorge over the ages. On the Armenian side you could see military barracks and observation stations -- ample places for the Armenians to watch the Turks as the Turks watched the Armenians.

At the edge of the path we searched for the Church of St. Gregory. This church was actually one of several churches in Ani dedicated to St. Gregory the Illuminator (c. 257-332 AD), whose missionary work led to Armenia becoming the first nation to adopt Christianity. Our books had described St. Gregory's as the best preserved church in Ani but all I could see was a foundation and half of a wall from some long forgotten structure.

"This can't be it," I said aloud to myself.

"It isn't," Berzan replied. "We must go down towards the river."

As we made our way around the foundation I saw the church, 100 feet below, perched on a cliff's edge. The sight was nothing short of extraordinary -- an ancient stone church standing guard over a gaping tear in the earth. The scene was straight from a fairy tale, begging to be photographed, though to my frustration the entire backdrop was filled with forbidden Armenia. My first reaction was to throw caution to the wind and snap a few photos, but those VIPs we spotted earlier were now inside the church as two soldiers stood on watch on the hilltop above it. Though one soldier appeared to have his attention elsewhere, the second soldier spotted me and kept his eyes on us as we walked down. As I descended the hill I lifted my camera as it hung around my neck and removed the lens cap to inspect the outer lens for dust. I blew at the lens, pretended to look frustrated, then tilted it horizontally to allow the dust to fall. I repeated the process three times, though as my camera went horizontal the third time I pressed the trigger, having no idea whether or not I'd capture the church. The soldiers did not react.

"I know exactly what you're doing," Susanne said over my shoulder.

Nearing the bottom of the path the VIPs began to climb up, passing us along the steps. I nodded my head and said "Iyi günler" to one of the generals. Another general approached, though he was wearing a different uniform and didn't look particularly Turkish. Not wanting to offend by speaking Turkish I simply nodded my head. Soon enough all the VIPs and their escorts cleared out of the area giving us some breathing room to inspect the church.

to one of the generals. Another general approached, though he was wearing a different uniform and didn't look particularly Turkish. Not wanting to offend by speaking Turkish I simply nodded my head. Soon enough all the VIPs and their escorts cleared out of the area giving us some breathing room to inspect the church.

Built in the early 13th century by a wealthy Armenian, the Church of St. Gregory is called Resimli Kilise (the Church with Pictures) by the Turks because of its collection of frescoes along its inner vaults. Though terribly vandalized and not as striking as the Akdamar frescoes, the paintings nonetheless captured a lost era of Armenian prosperity in Anatolia.

|

| Resimli Kilise (Church of St. Gregory), Ani. The land behind the church is Armenian territory. |

|

| Close-up view of Resimli Kilise's frescoes. |

"Remember how you take your pictures," Berzan said dryly. "Take it facing Turkey -- good. Take it facing Armenia -- not good."

I stood in front of the church, facing towards Armenia. "If I take a photo this close, no one will be able to see Armenia, right?" I commented as I snapped the photo. I looked up and saw a soldier looking down at me. He didn't seem to care either way.

|

| Ruins of Ani Cathedral |

We climbed back up the hill to the main path and headed to our next stop, Ani Cathedral (known to the Turks as Fethiye Mosque). The cathedral was built at the turn of the first millennium by Trdat Mendet, the master Armenian architect who also constructed Akdamar's Church of the Holy Cross. Depending on who was in charge of the city at the time, the cathedral was used as either a church or a mosque. Today it is Ani's largest freestanding structure, not counting the city walls. From a distance the cathedral looks like a drab brown box, but as we approached I could understand how it was used to strike awe in the heart of its parishioners. The cathedral soared high above the plain, forcing you to look up towards heaven as you admired it. If its enormous dome hadn't collapsed ages ago, it would have soared even higher, perhaps into legend as one of the great cathedrals of the Middle Ages.

A baby-faced soldier stood guard just outside the cathedral. He smiled shyly to me as we approached.

"Iyi günler," I said to him.

I said to him.

"Merhaba," he replied, politely nodding his head.

he replied, politely nodding his head.

Susanne, Berzan and I admired the cathedral from outside as the soldier looked on. "I wonder if it would be appropriate to ask him to take a picture of the three of us," I asked. Berzan took my camera and brought it up to the soldier, speaking to him in Turkish. I saw the soldier nod and take the camera from Berzan's hand. He then backed up onto a mound of rubble to snap the shot.

After the photo we went inside to inspect the rest of the cathedral. It was very dark inside despite the enormous hole in the roof caused by the collapsed dome. I hadn't realized how vast the structure was until going inside -- the vaults soared as high as any gothic cathedral in Europe. Incredibly, I could see graffiti carved into the vaults, well over 100 feet above my head. The lengths people would go to in order to desecrate a holy work of art -- it was beyond my comprehension.

|

Ruins of Menüçer Camii,

an 11th century Seljuk mosque |

Exiting the cathedral through its western door we came near the Menüçer Camii, Ani's oldest mosque. Built in 1072, Menüçer Camii is believed by some historians to be the first significant mosque built by the Seljuk Turks during their push into Anatolia from Persia. It didn't appear to be a mosque when compared to more common style of Ottoman mosques, with their graceful minarets and Aya Sofya-inspired domes. The Menüçer Camii was a rectangular structure with a smokestack-like octagonal minaret, more akin to an Armenian church. It was fairly likely that the Seljuks employed the local Armenians when building it, achieving a unique fusion of Seljuk-Armenian styles not commonly found elsewhere.

Turks during their push into Anatolia from Persia. It didn't appear to be a mosque when compared to more common style of Ottoman mosques, with their graceful minarets and Aya Sofya-inspired domes. The Menüçer Camii was a rectangular structure with a smokestack-like octagonal minaret, more akin to an Armenian church. It was fairly likely that the Seljuks employed the local Armenians when building it, achieving a unique fusion of Seljuk-Armenian styles not commonly found elsewhere.

Susanne and Berzan went inside the mosque while I scoped its outer walls. Realizing that there were no soldiers within view, I discreetly changed lenses and snapped a photo of the gorge and river below. As I walked inside the mosque I heard several people laughing. Susanne and Berzan were chatting in English with a Turkish soldier who had a huge grin on his face.

"How's it going, man?" the soldier said to me in what could only be native American English.

"This is Halil, the soldier from America I told you about," Berzan said as I shook the soldier's hand.

"You can call me Hal," Halil replied. "Halil's just my Turkish name - and my army name, I guess."

"To me you will always be Halil," Berzan joked. "If I remember, you were born in San Fran..."

"St. Louis, actually," Hal said, "But I grew up in Omaha."

"Ah yes, St. Louis," Berzan corrected himself. "Is that near where you live?"

"No, not at the moment," Susanne replied, "but we used to live in Chicago, which isn't too far from St. Louis."

"So if you don't mind me asking," I jumped in, "what on earth are you doing in the Turkish army, stationed along the Armenian border?"

"I decided to enlist," he said matter-of-factly. "My parents were from Trabzon but they settled in the US. We became a pretty typical American family, including getting a typical divorce, so they split up when I was a kid. I've been on my own and working since high school, and one day I thought that I just didn't know much about my heritage, my family, my culture. So I decided to drop everything and move to Turkey."

"Did you speak Turkish before coming?" Susanne asked.

"Nope," Hal replied. "It was pretty awful for a while. My sergeant would threaten me with latrine duty if I didn't learn fast, so I've learned a lot over the last 14 months."

"It must have been a huge shock to settle into this way of life," I commented.

"Tell me about it," he laughed, pulling out his old driver's license from his wallet. On it was a picture of a long-haired 20-year-old.

"I was such a freak to them when I joined," Hal continued. "I showed up to the recruitment office with sunglasses, hair down to my chest, earrings in both ears, a pierced tongue and nipple rings. They didn't know what to make of me. It was pretty cool... But overall the army's been great for me."

"Do you know anything about those VIPs who came through here earlier?" I asked.

"Yeah, they were Turkish and Armenian generals," Hal explained. "The governments have a monthly inspection protocol in which one side visits the other side's border facilities. It supposedly helps keep the peace."

"Apart from them we haven't seen any other visitors here," I added.

"We only get a few tourists a day," Hal continued. "Most tourists would rather party hard along the Aegean rather come here to the middle of nowhere. Fine with me -- I just hang out in the mosque and enjoy the view...."

We spent about 20 minutes chatting with Hal, hearing about his life in the military and his plans for afterwards. ("I'm going to move to Bodrum... It's like Fort Lauderdale but so much cooler...") At one point I joked about the policy against photographing Armenia, to which he responded by encouraging me to lean out the window and take a few shots. From the window I could see the remains of an ancient bridge stretching across the gorge.

"When is it from?" I asked Hal, pointing to the bridge.

"It's from the Silk Road, actually," Hal explained. "That bridge would lead to Persia or to Anatolia, depending on which way you went. Whoever controlled that bridge controlled this part of the Silk Road."

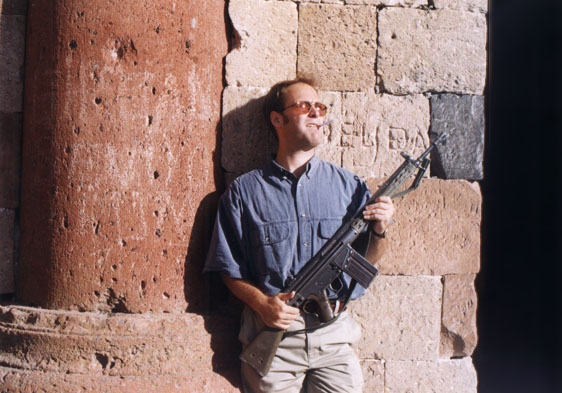

After a while we noticed it was approaching 4pm, which meant we had to wrap up our visit within the hour in order to get out of the ruins before the soldiers closed it after 5pm. Susanne and I both offered to take pictures of Hal in uniform to send to his family. He then traded hats with Berzan, handing him his G-3 automatic rifle for an impromptu Turk-versus-Kurd photo.

"Mind if I try?" I asked somewhat hesitatingly after they finished posing.

"Be my guest," Hal replied, taking the rifle from Berzan and giving it to me.

"You'll need this as well," Berzan added, sticking an unlit cigarette in my mouth. Images of Lee Harvey Oswald posing with his Menlicher-Carcano rifle passed through my mind as Susanne took the photograph. It was a strange feeling, holding a rifle just shy of the Armenian border. In the two days we had been in the heart of Kurdistan, we had encountered many well-armed soldiers. Numerous times in my mind I had paraphrased a quote from a John Sayles movie: "There are only two types of men here, my friend: Men with guns and men without." It had been true in Sayles' fictional account of a Central American peasant uprising, and it was true here in Kurdistan. Either you had a gun or you didn't; either you were the powerful or the powerless. For the brief moment I gripped the Turkish rifle, I felt what it was like to be on the other side.

Having said our goodbyes with Hal we walked north from the mosque along the western edge of the Ani plateau. A vast, verdant valley stretched far westward, a small river meandering through it. The silence of our walk was broken by an irate donkey somewhere in the valley, hee-hawing as if his life depended on it.

"So Hal has been in the army for 14 months," Susanne commented. "That means he has only four months to go?"

"That's the way it is now -- 18 months," Berzan said. "When I joined the army many years ago was only 14 months. They changed the rules when my younger brother Feyzel was in the army. Just when he was approaching his final month the Turks changed the rules, making it 18 months. He was stuck for an extra four months. It was really terrible for him and my family."

"Watch where you step -- land mines," Berzan added, pointing at the cow patties that littered the pathway."

Nearing the city walls again we reached our last stop at Ani: the Gagikashen, or King Gagik I's Church of St. Gregory. Built 1000 years ago by master architect Trdat in honor of the end of the first millennium, the church was one of the most ambitious construction projects at Ani. Trdat designed his millennium church as a reconstruction of Zvart'nots Cathedral, a magnificent 7th century Armenian church that was destroyed during an earthquake. Gagikashen may have been too ambitious, though, for its great dome collapsed soon after it was completed. Today the church is but a circular foundation littered with shattered marble walls and columns. Ruined wall fragments the size of boulders made visiting the church a little tricky at times. Our exploration was monitored by a cow dining on the grass outside of the church. I tried to get a closeup of the cow but he refused to cooperate, walking away every time I approached.

It was almost 5pm by the time we returned to the gatehouse on the opposite side of the city walls. The soldiers returned our passports, allowing us to make the 30 minute drive back to Ani. Even though we had spent just over three hours in the ruins, Susanne and I were both pretty tired.

"I think it was well worth it," I said, leaning back in my car seat.

"Absolutely," Susanne replied from the front seat.

|

| A soldier on patrol, Ani. Note the Church of the Redeemer, sheared in half by a lightning strike. |

Berzan gave us a couple of free hours back at the hotel to shower and rest before heading out for dinner. At 7pm we walked from the hotel to Kazim Pasa Caddesi, which had several restaurants along the road. We had dinner at the recently relocated Yesilyurt Lokantasi,

which had several restaurants along the road. We had dinner at the recently relocated Yesilyurt Lokantasi, eating Turkish pizzas in a high-ceiling dining room decorated with the pelts of bears, foxes and what appeared to be ferrets. Berzan ordered another plate of çig köfte, the raw meatballs that had surprised us the previous night. Just as Susanne and I were both trying to find a way to decline politely, Berzan tasted one of the meatballs and said, "Do not eat them tonight. They are not as good as in Van. Your stomachs would not like them."

eating Turkish pizzas in a high-ceiling dining room decorated with the pelts of bears, foxes and what appeared to be ferrets. Berzan ordered another plate of çig köfte, the raw meatballs that had surprised us the previous night. Just as Susanne and I were both trying to find a way to decline politely, Berzan tasted one of the meatballs and said, "Do not eat them tonight. They are not as good as in Van. Your stomachs would not like them."

Left with a full plate of uneaten meatballs, Susanne commented, "When I was a kid I was an expert in hiding uneaten food."

"Good idea," Berzan smiled, hiding an uncooked morsel under a piece of flatbread.

Following dinner we strolled around the streets of central Kars, watching shops closing up for the evening and kids playing soccer along a street that had been repaved earlier in the day. It was surprisingly chilly outside, perhaps in the mid 50s. Once again I was reminded that Kars, Turkey's foothold in the Caucasus, is also the Turkish word for snow. As we strolled by the Otel Kervansaray we overheard folk music coming from a suite high above the street.

"It almost sounds like Irish music," Susanne said.

"It's traditional wedding music," Berzan replied. "Not Turkish or Kurdish, though. I think it may be Kirghiz music."

Berzan then noticed I was looking up at marquee for the Otel Kervansaray. "Not a good place," he said. "You must be careful where you stay in Kars sometimes. Have you heard of the Natashas?"

"Yeah," I replied, "we had read about Natashas the day before in Lonely Planet." Natashas are Russian prostitutes that began streaming across the Turkish-Georgian border after the fall of the Soviet Union. Though rarely spoken of publicly here, prostitution is tolerated in some parts of Turkey as long as it is discreet, and many residents now complain that the high-heeled, bleach-blonde Natashas are bringing it too far out of the closet.

Not far from the restaurant we found a small pastane that was still open for business (eateries close early in Kars, we discovered). The three of us sat in the back of the cafe, near a large fish tank populated with five or six tropical fish. The head colds that Susanne and I were fighting were acting up again, so we asked a waiter if they had apple tea.

"Elma çay var mi?" I asked, with Berzan beside me, smirking at my Turkish.

"Yok," the waiter replied, adding something I didn't understand.

the waiter replied, adding something I didn't understand.

"No apple tea until winter," Berzan explained. "Here in the east it is a seasonal drink. He said they have cherry tea, though."

We each ordered cherry teas and sat quietly, admiring the fish tank. Berzan kept reaching his right arm around his neck, pawing at his left shoulder blade.

"What is it?" Susanne asked.

"It is my shoulder," he said, squirming in obvious discomfort. "My muscle is -- how do you say it -- moving very fast and tight."

"It sounds like a cramp," I said.

"Yes, that's the word for it -- cramp. I have never had one like this before. I must be coming down with a cold."

"If you'd like I have some pain medicine at the hotel," I offered. "I sometimes have back pain so I bring it whenever I travel with a backpack."

"Okay, let's see how it is when we go to the hotel," Berzan replied.

Our cherry tea soon arrived and Berzan tapped the waiter on the arm to stay for a minute. Berzan tasted the tea and spoke to him in Turkish, causing the waiter to scurry away to the kitchen. He returned with a container of instant cherry tea mix and a spoon. Berzan took the bottle and scooped a spoonful into his tea glass, offering some to us as well.

"Cherry tea should not be weak," he said, stirring the dissolving powder with his spoon.

The three of us finished our teas quickly, all eager to get back to the hotel for some sleep. Berzan followed us to our room for the Naproxen pills I had promised.

"Tomorrow we can sleep in," Berzan said, wrapping the Naproxen tablets in a tissue. "We can meet for breakfast at 9am and leave after that. We will be at Dogubeyazit for lunch."

I thought about Dogubeyazit as I went to bed. It might have been easier for us to have planned our visit to Kurdistan for the beginning of the trip instead of the end, but Susanne and I agreed that wrapping up our trip at Dogubeyazit's Ishak Pasa Palace near the foot of Mount Ararat would be a climactic finish. We had come so far to the remotest corner of Anatolia -- and tomorrow we would go to Mount Ararat to visit the most magnificent Kurdish palace in the Middle East. For the first time I realized the trip was nearing an end.

approached Berzan's window and took our identification. Berzan was then asked to step out of the car to open the trunk. A moment or two later the jendarma knocked on the window to my left. I rolled down the window to find out what was going on just as the jendarma began to speak swiftly in Turkish.

approached Berzan's window and took our identification. Berzan was then asked to step out of the car to open the trunk. A moment or two later the jendarma knocked on the window to my left. I rolled down the window to find out what was going on just as the jendarma began to speak swiftly in Turkish.