The Topkapi Treasury was equally stunning, with its fine collection

of jewel-encrusted thrones, royal medals, and the famous Topkapi

dagger, made out of one of the largest carved emeralds in the world.

From Topkapi we returned to the square between Aya Sofya and the

Blue Mosque, relaxing at a garden cafe just below the giant church. I

briefly ran around the corner to a kontürlü telefon

kiosk, outdoor public pay phones where you could make a telephone

call and then pay an attendant. Susanne and I needed to get ahold of

Aydin in order to find out if he could get us a room at the Kalehan

hotel in Selçuk. I called Aydin's cellphone but was given a

recording in Turkish and English that said his phone was out of

calling range -- he was probably on the road with a tour group. The

attendant told me the call was free because I wasn't able to connect.

As I walked away from the kiosk I heard him say, "Sizin kitab,

effendim" -- "Your book, sir." I turned around and noticed I

had left our Lonely

Planet book on the counter. I can only imagine what trouble I

would have been in with Susanne if I had lost the book that

contained all of our notes and plans.

Back at the cafe I rejoined Susanne to finish my Turkish coffee and

talk about our plans for the next few days. The two of us were

getting hungry so we decided to pay our bill and find a full-service

restaurant for lunch. The waiter was sitting a few tables from us,

concentrating on his newspaper. I walked over and asked for the bill

and he quickly folded up the paper. As he did this I noticed it was

full of pictures of naked women. He gave me the bill as well as a

grimace of embarrassment.

|

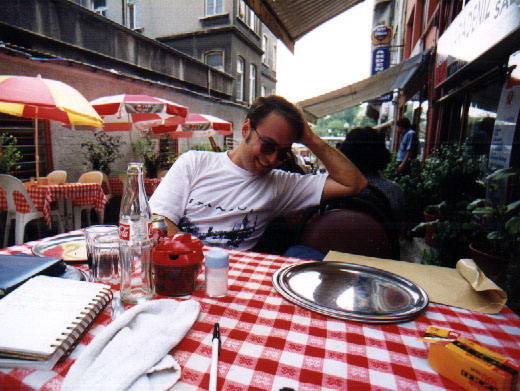

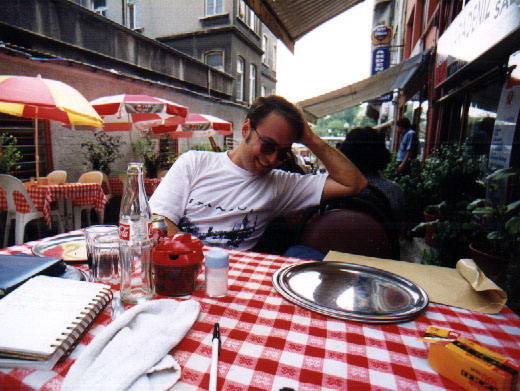

| Andy hanging out at the

Karadeniz Pideci |

Uphill just behind Divan Yolu and the Sultanahmet tramway tracks

we found the Karadeniz Aile Pide ve Kebap Salonu -- The Black

Sea Pizza and Kebap Salon. We sat outside under a

red awning as Susanne ate a vegetarian Turkish pizza and I ate a

spicy plate of köfte

Salon. We sat outside under a

red awning as Susanne ate a vegetarian Turkish pizza and I ate a

spicy plate of köfte  kebap. A neighborhood cat

reconnoitered around our table, scouting for scraps. He didn't seem to

care for pizza crusts but was more partial to my köfte meat.

Just around the corner from the Karadeniz was the Sinem Internet

Cafe, where we were able to use their clean bathrooms for free and

check email for 200,000 lira (50 cents), or the cost of two public

bathroom visits in any part of the city.

kebap. A neighborhood cat

reconnoitered around our table, scouting for scraps. He didn't seem to

care for pizza crusts but was more partial to my köfte meat.

Just around the corner from the Karadeniz was the Sinem Internet

Cafe, where we were able to use their clean bathrooms for free and

check email for 200,000 lira (50 cents), or the cost of two public

bathroom visits in any part of the city.

We still had a little time before having to go to the airport, so

Susanne and I strolled down to the Hippodrome. Now a relaxing

public garden, in its heyday the Hippodrome was the city's imperial

racetrack. Along with its famous horse races, the Hippodrome was

also the center of political intrigue and conspiracy. During the

summer of 1826, the Hippodrome witnessed the end of the Ottoman

Empire's legendary squadron of soldier-slaves, the Janissaries.

Founded in the mid-1300s by Sultan Murad I as his imperial cavalry

guard, the Janissaries (Yeni Çeri, or "new troops") were

young Christian men, largely from the Balkans, who were captured

and enslaved during Ottoman conquests. This enslavement, however,

was also an opportunity for personal prestige and privilege.

Janissaries were trained to serve as the empire's elite fighting force,

and each soldier-slave was able to rise to the highest levels of

military service based on personal merit.

|

Anatolian Trivia

The Jannisaries were immensely proud of the fact that they were the

best-fed troops in the Ottoman Empire. So much so, their ranks were

organized on culinary terms. As a whole, the Janissaries referred to

themselves as the ocak (the hearth or fireplace); their symbol was a

sacred cooking cauldron. Among the terms they used to represents

their individual ranks were çorbaci (the soupmaker),

asçibasi (the chief cook), gözlemici (the pancake

maker) and the çörekci (the cake maker). On the occasions when they began a rebellion against the sultan, they would signify their ire by turning over their giant cauldrons of rice pilaf. Even today, the Turkish expression "to overturn the cauldrons" means to rebel against someone.

|

During the 15th and 16th centuries, the Janissaries were the pride of

the Ottomans and the scourge of Christian Europe. In medieval cities

like Budapest and Belgrade, the "Turk bells" would ring to warn

citizens of their approach. At the height of the Ottoman Empire,

Suleyman the Magnificent's Janissaries penetrated deep into central

Europe, fighting their way to the gates of Vienna. But in the 17th and

18th centuries, the Janissaries began a long period of decline,

succumbing to the temptations of corruption and political

opportunism. On more than one occasion, Ottoman sultans were

deposed and even assasinated during coup d'etats staged by the

Janissaries. Numerous sultans were forced to placate the greety

Janissaries with ill-conceived military campaigns, many of which

furthered the decline of the empire.

By 1826, Sultan Mahmud II was fed up with the intransigence and

avarice of the Janissaries. Two decades earlier they had staged a

coup against his reform-minded brother, Sultan Selim III, partially

because he tried to impose European-style military uniforms on its

ranks. Selim was deposed and executed, and Mahmud would have

met the same fate if it hadn't been for a loyal slave who hid him

inside the unlit furnace of the royal baths. Proclaimed sultan in a

swift counter-coup later that same day, Mahmud longed to carry out

his murdered brother's dream of reforming the empire into a

modern imperial state - as well as to exact revenge on the

treacherous Janissaries.

Knowing the Janissaries would revolt if pushed hard enough,

Mahmud announced a series of radical military reforms. The

Janissaries, who were stationed in barracks inside the Hippodrome,

initiated their revolt by defiantly turning over their giant cooking

cauldrons and marching through the narrow streets of Sultanahmet

towards Topkapi Palace. There they were met with a barrage of

musket fire from soldiers loyal to the sultan. The Janissaries,

surprised by the resistance, retreated to the confines of the

Hippodrome, where they were unceremoniously slaughtered by

Mahmud's loyal cavalry and artillery squadrons. Over 4,000

Janissaries perished in the attack, ending the military order once and

for all, and opening the opportunity for Mahmud to reform his

empire into a modern, European-style nation.

|

| Young boy in

circumcisional regalia |

Today, of course, there is no sign of the violence and intrigue that

once plagued this historic place. Scores of families were strolling

along the Hippodrome's garden, enjoying the early afternoon

sunshine. Streams of people washed their hands in Kaiser Wilhelm's

Fountain, a turn-of-the-century monument given to the sultan by the

kaiser during a visit to Constantinople. A young boy dressed in the

customary circumcision costume was herded into position by his

parents, who proudly snapped pictures of him. Susanne approached

family and asked if she could take a photo. The parents graciously

said yes, to the chagrin of the boy. Further down the mall we visited

the obelisk of Theodosius, an ancient Egyptian obelisk imported to

Constantinople by the emperor Theodosius in 390 AD. Theodosius

mounted the obelisk on a marble pedestal decorated with images of

his royal court and scenes promoting his battle prowess.

At the eastern end of the Hippodrome, not far from the Blue Mosque,

Susanne and I stopped at Cafe Mesale , a shady garden teahouse

sumptuously decorated with hanging carpets, Ottoman pillows and

blazing torches. Susanne ordered a tea while I ran around the corner

once again to call Aydin at the telephone kiosk. This time I managed

to get ahold of him; he told me we had reservations at the Kalehan

Hotel in Selçuk, and that the hotel recommended that we catch

a dolmus

, a shady garden teahouse

sumptuously decorated with hanging carpets, Ottoman pillows and

blazing torches. Susanne ordered a tea while I ran around the corner

once again to call Aydin at the telephone kiosk. This time I managed

to get ahold of him; he told me we had reservations at the Kalehan

Hotel in Selçuk, and that the hotel recommended that we catch

a dolmus to town from just outside the

Izmir airport. Aydin warned me it would be a bit of a walk from the

airport to the dolmus stop, but he said it probably wouldn't

take too long.

to town from just outside the

Izmir airport. Aydin warned me it would be a bit of a walk from the

airport to the dolmus stop, but he said it probably wouldn't

take too long.

|

Turkish Pronunciation

Interested in learning how to pronounce the Turkish words mentioned in this journal? Check out my Turkish pronunication guide!

|

As I returned to the cafe our waiter was talking to a pair of Turkish

women who were sitting to our left. They ordered some kind of cake,

so the waiter dashed around the corner and returned with a platter

topped with a silver lid. He placed the platter on the table and raised

the lid. To everyone's surprise a small black bunny jumped out into

one of the women's laps. She let out a brief scream and then laughed

hysterically, petting the frisky rodent. The waiter then came to our

table and asked if I wanted anything.

"Bir Türk kahve ve bir sisede memba su,

lütfen," I said, trying to ask for some Turkish coffee and a

bottle of water.

"You want coffee and what?" he said to me in English, confused.

"Uh, a bottle of water," I stumbled. "Sisede memba

su."

"Oh! Mem-BAH su," he laughed. "Not MEM-ba su -- mem-BAH su."

"Sisede mem-BAH su, then," I corrected myself,

accentuating the proper syllable this time around.

"Very good," he answered. "Now you can be a Turk."

We sat at Cafe Mesale for an hour, slowly sipping our drinks

and watching the black bunny hop around the table neighboring us.

Every few minutes we'd see a large seed pod of some kind come

crashing down from the tree above us, colliding with the cobblestone,

the tables, even a Spanish tourist's head. A little boy was going

around from table to table, picking the pods off the ground and

stuffing them in his mother's purse. One of them pounded me on the

shoulder and landed just off the table. I picked it up and found a

large nut encased in a thick shell.

"They are very good," our waiter commented as he saw me pick it

up.

"What kind of nut is it?" I asked.

"Kestane," he replied. "I don't know the name in English, but

they are eaten roasted. You can buy them roasted all over

Istanbul."

"They must be chestnuts, then," Susanne said. "Someone was selling

them near the Egyptian Bazaar yesterday."

I cracked the nut on the table and revealed the inner flesh of what

was indeed a chestnut. I ripped off a piece and tasted it --

unpleasantly sour.

"I told you," the waiter admonished me, seeing the grimace on my

face. "You should roast them first..."

Around 2:30pm we returned to the guesthouse to pick up our

backpacks and catch a taxi to the airport. The six-million-lira taxi

ride took less than 20 minutes, giving us plenty of time to check in

for our flight and hang out at the airport restaurant, drinking

lemonade and splitting a piece of pecan pie. Our flight was delayed

by 20 minutes but we eventually were allowed to board a transport

bus which would take us to the plane. The bus rode around the

tarmac for what seemed to be an eternity. We drove from terminal

to terminal, passing what appeared to be entire fleet of Türk

Hava Yollari (Turkish Airlines). Each plane was christened with

the name of a different Turkish city. In the 15 minutes we spent

circling the tarmac we managed a grand tour of the country:

Kusadasi, Ankara, Trabzon, Van, Edirne. Just as it seemed the only

place left for us to go was back to the terminal gate, the bus pulled

up next to Gaziantep -- a THY Boeing 767. Finally we were on our

way to Izmir.

The 45-minute flight passed by quickly as we scribbled in our

journals and noshed on an airline snack of packaged fruit cake. A six-

foot blonde woman who looked like Turkey's answer to Pamela Lee

sat to our right, reading some kind of engineering journal. On the

whole it was pretty uneventful, though I was eager to get to Izmir in

order to figure out how we would reach Selçuk. Izmir's airport

is south of the city center, along the road to Selçuk, but the

Izmir bus station was north of the city. If we were to take the bus,

we'd first have to go north through Izmir, Turkey's third largest

metropolis and currently the host of an enormous international trade

fair. Assuming we could get through the city to the otogar, we'd have

to catch a second bus to Selçuk, backtracking through Izmir,

past the airport again, before arriving at our destination. It wasn't a

scenario I relished, especially since there was a possibility that we

wouldn't arrive at the Izmir otogar in time for the last evening bus to

Selçuk. Hopefully we wouldn't have a problem figuring out

Aydin's suggestion to catch a dolmus instead.

instead.

Once inside the Izmir arrival terminal we looked around for a travel

information desk. Unfortunately the terminal hosted only a trade fair

bureau desk and a currency exchange. Just outside the terminal I

approached a policeman to find out if there was by any chance a

direct bus to Selçuk.

"Pardon, Memur Bey -- Selçuk otobus var

mi?"

-- Selçuk otobus var

mi?" I asked.

I asked.

"Yok," the policeman

replied.

the policeman

replied.

"Dolmus var mi?"

"Yok," he said again, clicking his tongue.

It looked like we were stuck finding that dolmus station

somewhere beyond the airport. Susanne and I walked away from the

airport, down a deserted road towards a police checkpoint. Several

paramilitary jendarma stood guard outside the checkpoint. They

could tell we looked a little lost. One of them called out to us in

Turkish, though I couldn't understand what he said.

"Iyi aksamlar, Memur Bey," I said to him as

we approached. "Ingilizce

konüsüyormüsünüz?"

Memur Bey," I said to him as

we approached. "Ingilizce

konüsüyormüsünüz?"

"Ingilizce?," he replied. "Yok.... No Ingleesh." As he spoke I noticed he

had the brightest blue eyes I had ever seen.

I struggled to find the right words in Turkish to explain that we were

looking for a dolmus to Selçuk. "Uh.... Bizim... gidiz...

Selçuk. Dolmus nerede?"

"Ah, dolmus," he replied. That was all I could understand as

he spoke to me rapidly in Turkish.

"Uh, yavas, lütfen,"

lütfen," I requested, asking him to slow

down. The policeman nodded his head and spoke slower, but I could

still not understand a word he said. He did, however, point down the

road in the other direction. Hoping that he was telling us to go the

other way, we thanked him and backtracked towards the airport.

I requested, asking him to slow

down. The policeman nodded his head and spoke slower, but I could

still not understand a word he said. He did, however, point down the

road in the other direction. Hoping that he was telling us to go the

other way, we thanked him and backtracked towards the airport.

"That soldier had the most beautiful eyes I've ever seen," Susanne

said.

"Yeah, even I noticed them," I replied.

We walked around the perimeter of the airport along the edge of a

highway. I didn't feel great about our predicament. An old man with

a walking stick approached us from the other direction.

"Pardon, effendim," I said. "Selçuk

dolmus nerede?"

I said. "Selçuk

dolmus nerede?"

"Orada," he replied, pointing

far down the highway.

he replied, pointing

far down the highway.

"Kaç saat?" I continued, wanting to know

how far of a walk we had ahead of us. "On dakika?

I continued, wanting to know

how far of a walk we had ahead of us. "On dakika? Otuz dakika?"

Otuz dakika?"

"Anlamadim," he responded. "Otuz dakika." I

don't know -- 30 minutes...

he responded. "Otuz dakika." I

don't know -- 30 minutes...

His answer didn't boost my confidence, so I suggested we return to

the airport and ask a few more people what options we had. I was a

little surprised that no one here spoke a word of English, considering

we were at a major international airport, but there wasn't much we

could do about it.

Entering the airport parking lot we reached a small sentry post. A

parking attendant sat inside, eating his dinner from a styrofoam box.

"Pardon, Memur Bey," I said yet again, "Selçuk dolmus

var mi?"

"Yok dolmus," he replied. "Bir dakika, lütfen..."

lütfen..." He then picked up the phone

and placed a call, speaking to someone for about 30 seconds before

hanging up. The sentry pointed to the terminal and said,

"Selçuk -- on besdakika." It appeared that there was a

bus or some other vehicle going to Selçuk at six o'clock, 15

minutes from then.

He then picked up the phone

and placed a call, speaking to someone for about 30 seconds before

hanging up. The sentry pointed to the terminal and said,

"Selçuk -- on besdakika." It appeared that there was a

bus or some other vehicle going to Selçuk at six o'clock, 15

minutes from then.

"Alti saat Selçuk, degil mi?" I asked, confirming the time.

"Var," he replied, nodding

his head once.

he replied, nodding

his head once.

Susanne and I walked quickly towards the terminal, up a walkway

from the parking lot. As we ascended the walkway I realized we had

entered a small train station. A train! It never occurred to me there

was a train station at the airport. I rushed to the counter and asked a

woman in Turkish if there was indeed a train to Selçuk.

"Yes," she replied in English. "Ten minutes on Platform One."

I was quite pleased with myself as we stood on the platform. "I'm so

glad I learned some Turkish," I said happily. "Without it there's no

way we could have figured this out. Finally some language practice

pays off."

A few minutes later we saw a train approach the platform. For some

reason it stopped just short of the platform. An attendant climbed off

the train and waved his hand to have us walk down the platform to

the train. Just before we reached the engine car I noticed two

German backpackers getting off the train. They were drenched in

sweat, with one of them cursing to himself loudly. It wasn't a

positive sign. We climbed down the end of the platform into the

grass and were helped onto the train by some passengers. As we got

on board we realized we were in for a rough ride: standing room

only, dozens of people packed like sardines in 100-degree heat.

We immediately took off our backpacks and placed them by our feet,

knowing there was no room on board for us to wear them. I managed

to reach over two people in order to get my left hand wrapped

around a metal pipe for support. Susanne, in turn, grasped my

shoulder to stay balanced. We were the only people on the train who

weren't Turkish. Old men in caps and baggy trousers wiped sweat

from their brow as their headscarved wives stood behind them. A

group of teenage boys maintained a polite distance from Susanne,

careful not to give offense in some way. Even though there were 40

or 50 people squeezed into the car it was unusually quiet, save the

rolling clatter of the tracks passing below us.

Susanne had an enormous smile on her face. "What the hell," she

said, shrugging. "This is going to be an adventure."

About five minutes into the ride I could feel a moist film of sweat

forming on my forehead. I used the sleeve of my free arm to wipe

my face. An old man with a scruffy five o'clock shadow smiled at me,

wiping his forehead in turn.

"Çok sicak, çok sicak," I said to him, commenting on

how hot it was. Several people glanced up when they heard me

speak Turkish.

I said to him, commenting on

how hot it was. Several people glanced up when they heard me

speak Turkish.

"Allah Allah, çok sicak," the man

answered, a large smile forming on his face. "Nerede gidisiniz?"

çok sicak," the man

answered, a large smile forming on his face. "Nerede gidisiniz?" he then asked, wanting to know

our destination.

he then asked, wanting to know

our destination.

"Selçuk," I replied, eager to find out how far away the town

was. "Selçuk Kaç saat?"

"Kirk kilometer," he answered. "Altmis dakika." We had 60 minutes

to cover about 40 kilometers, apparently.

As we stood there, swaying with the crowd as we braved the intense

heat, Susanne looked at me and pointed to her backpack.

"I have Wet Wipes, you know," she said quietly to me.

"I was just thinking that," I replied. "I don't know if we can use them

if we don't have enough to share, though."

"I know," she agreed. "I think we have enough." Susanne pulled out a

packet of moist towelettes, opening it up and handing me one. As I

unfolded it she offered another packet to the old man and his wife.

"Tesekkürler, yok," he said, bowing his head and touching his

chest with his hand, politely declining the offer.

"Lütfen, effendim," I insisted, showing him my unfolded Wet

Wipe.

"Tamam, tamam," he replied, accepting my offer.

"Tesekkür ederiz."

he replied, accepting my offer.

"Tesekkür ederiz." He removed two towelettes,

using one and passing the other to his wife.

He removed two towelettes,

using one and passing the other to his wife.

Susanne continued to pass the towelettes around the crowded car: to

a young mother and her child, to the group of teenage boys in soccer

shirts. One by one they dabbed the lemon-fresh towelette on their

foreheads, enjoying the brief respite from the heat. For a few

moments we were the happiest car on the train.

The old man's wife leaned forward and offered me a small packet of

hazelnuts, a Turkish favorite. "Sag olun," I said, thanking her. I opened

the packet and tossed a couple of nuts in my mouth, offering them to

Susanne as well.

I said, thanking her. I opened

the packet and tossed a couple of nuts in my mouth, offering them to

Susanne as well.

"Cok güzel!" I exclaimed, which caused the

woman to laugh. I then offered the nuts to several people including

the woman who handed them to me. They all politely declined,

wanting me and Susanne to enjoy them ourselves. I unbuttoned my

shirt's front pocket and put the remaining nuts inside. A minute or

two later the old man tapped my chest to get my attention. He

motioned to his own shirt pocket and pretended to button it. I

assumed he was trying to tell me to keep it closed for safety. I

nodded my head and smiled, quickly buttoning the pocket.

I exclaimed, which caused the

woman to laugh. I then offered the nuts to several people including

the woman who handed them to me. They all politely declined,

wanting me and Susanne to enjoy them ourselves. I unbuttoned my

shirt's front pocket and put the remaining nuts inside. A minute or

two later the old man tapped my chest to get my attention. He

motioned to his own shirt pocket and pretended to button it. I

assumed he was trying to tell me to keep it closed for safety. I

nodded my head and smiled, quickly buttoning the pocket.

Despite the rotisserie oven conditions I thoroughly enjoyed the train

ride, though by the time we reached Selçuk I was more then

ready to disembark. As the trained pulled into town I looked over at

the old man to confirm our present location. "Selçuk!

Selçuk burada!" he said, shooing us off the train

in an endearing kind of way. We stepped onto the platform and were

greeted by a blast of cool, fresh air that made me realize just how

unpleasantly sweaty I had become.

he said, shooing us off the train

in an endearing kind of way. We stepped onto the platform and were

greeted by a blast of cool, fresh air that made me realize just how

unpleasantly sweaty I had become.

As we walked out of the station a pretty Turkish woman approach us

and asked in English, "Are you looking for a hotel?"

"No thanks," we replied. "We are staying at Hotel Kalehan."

"It is a little expensive," she replied. "I can take you somewhere nice,

but cheaper."

"That's okay, we're meeting friends," I lied, hoping to get out of the

situation.

|

| Ruins of a Roman

aqueduct, Selçuk |

"Okay," she replied, "Follow me and I'll show you where to go."

"No, that's all right," I said. "We can find it."

"Please," she insisted, heading out the exit. Since we had to go in that

direction anyway we followed her, though I wondered how much of

a tip she expected (on more than one occasion we've had scam artists

try to lure us from bus and train stations to an overpriced hotel). Just

outside the station we found ourselves standing under the remains of

a giant Roman aqueduct, its bridge-like stonework soaring high

above us. We walked through an open square with a war memorial

towards a tree-lined pedestrian street.

"Walk straight ahead until you reach the main road," she said. "Take

a right and you will find the Kalehan just below the castle. Have a

nice time in Selçuk...." Before I could even contemplate a tip

she waved at us and walked away. Apparently I had underestimated

her gesture. Unlike the people of so many other countries we had

visited in the past, every Turk we met seemed eager to be friendly

to us just for the sake of friendliness. It made me think to myself

how much I was enjoying this country.

Susanne and I walked along the street, passing a long row of garden

cafes where locals and tourists alike dined on kebaps and drank

bottles of Efes beer.

"This is really adorable," Susanne said.

"It's so much nicer than I expected," I replied. "I already wish we

had an extra day to hang out here."

the day before; as

massive as it was, Aya Sofya's scaffolding only disturbed one

particular section of the church. Here at Topkapi Sarayi

the day before; as

massive as it was, Aya Sofya's scaffolding only disturbed one

particular section of the church. Here at Topkapi Sarayi it felt like the entire palace was

a hard-hat zone. Having experienced the sublime beauty of palaces in

India, Thailand, Cambodia and elsewhere,

Susanne and I had expected Topkapi to be just as magnificent. We

were both rather disappointed.

it felt like the entire palace was

a hard-hat zone. Having experienced the sublime beauty of palaces in

India, Thailand, Cambodia and elsewhere,

Susanne and I had expected Topkapi to be just as magnificent. We

were both rather disappointed.