As we returned to the car Berzan pointed across the street to a short man with gray hair and a five o'clock shadow. "That's my friend Hasan," Berzan said. "He just got back from China."

Berzan called over to Hasan and got his attention. The plump man gave Berzan a broad grin and joined us for a walk through the town's Iranian bazaar. This small market specialized in commercial goods brought in from Iran, including radios, computer parts, light bulbs and coffee makers, as well as other household products. Berzan and Hasan chatted away in Kurdish as Susanne and I peered through the shops, examining their assortment of goods. As Berzan talked with a shop owner Hasan came over to me and talked about his recent trip. Over the course of 163 days he led a caravan from China to Turkey via Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Iran. It sounded like a wonderful, difficult journey.

Having completed a loop around the market, the three of us said goodbye to Hasan and returned to the car. As we stopped for gas, Susanne asked Berzan to tell us the tale by Turkish storyteller Nasreddin Hodja that he had eluded to yesterday after a military checkpoint.

"One day Hodja decided to sell his mule at the market," Berzan began. "There were many people interested in buying the mule that day, so they each got a chance to look at it. Each time a person went up to the mule, they checked its teeth to see how old it was, to see if it was healthy. One after another, people visit the mule, examine its teeth and leave. In the end no one buys it, and Hodja is stuck with a mule that smiles every time it sees someone. Sometimes I feel like Hodja's mule."

Sometimes I feel like Hodja's mule. With each checkpoint, Berzan did what was expected of him as the Turks examined his identification, his car, even his face. And with each checkpoint, we too had learned to react as had Hodja's mule -- retrieve our passports, smile, and hope nothing went amiss.

|

| A small twister meanders across a field |

Leaving the city limits of Dogubeyazit I noticed a swirl of dust in a farmer's field. The swirl grew higher and higher until it formed a small twister.

"Do you see the twister?" Berzan said, pointing out the window. "They are very common around here. It isn't strong enough to be a problem, though."

As we passed the twister Berzan increased the volume of his stereo. Soon afterwards the man singing on the tape began to speak in English as orchestrated Kurdish music dramatically coursed around him. He then switched his lyrics to Turkish, Arabic and Kurdish.

"Who is this?" I asked Berzan.

"It is Sivan Perwer," he replied. "He is Kurdish, but he lives in Germany. He is originally from Turkey though his family fled to Syria. Sivan Perwer is the greatest Kurdish singer. He can never come home because of what he sings. The Turks would arrest him."

We turned off the road and headed along the main highway to Van. After driving for a minute or two I noticed Berzan began to pull over the car to the side of the road. My first reaction was that he wanted us to get out and take a picture of Mount Ararat one last time, which would soon disappear in the distance. As the car slowed down along the shoulder of the road, I could hear the sound of sirens behind me. It appeared we were being pulled over by police -- were we driving too fast?

I reached into my pocket to pull out our passports, sure that we would need them. A small two-door police car pulled over to our left. A policeman was leaning out the passenger window with a large automatic rifle pointed up into the air.

"Get out of the car," I heard Berzan say quickly.

While turning to open the rear left door I felt someone's hand grab my arm and yank me out of the car. It was so fast I could barely process it, but I realized it was the police officer with his large automatic rifle in his other hand. The next thing I knew I was being thrown against the back of the car spread-eagle, the soldier screaming in my ear while another soldier was frisking Berzan near the front of the car as Berzan shouted at him. Susanne appeared to be standing alone, away from the car, but I couldn't really tell. Were there other cops? What did they want? What the hell had we done?

I then felt a sharp pain in the back of my right thigh, punctuated by yelling in my ear. Had I been kicked? Smacked with the rifle butt? Before I could process what was happening the soldier kicked the inside of my left foot, causing my legs to swing out into a an even more vulnerable spread-eagle position.

My mind went blank. I wasn't scared, nor did I feel angry. I wasn't sure why we had been pulled over or why they were doing this to us. All I knew was that our lives could be in a lot of trouble, and the only thing that might get us out of that trouble was in my left hand. I held onto our passports for dear life.

"Amerikaliyiz! Biz Amerikaliyiz! Bizim pasaportlar!" I yelled, holding up our passports while trying not to raise my hands off the back of the car. The second soldier came over to me from where Berzan was being frisked and took the passports out of my hand. He thumbed through them quickly and said something loudly to me in Turkish.

"Get back into the car," Berzan said, still spread-eagle on the front of the car. "Get in now."

Not sure if this was Berzan's translation or suggestion, I looked over at the second cop. He nodded his head and motioned to the back seat of the car as he allowed Berzan to stand up straight. Berzan and the first cop began to yell at each other as Susanne and I returned to the car. It appeared that our passports would grant us safe conduct, though Berzan's future was far from certain.

Once inside, I took a deep breath as soon as I closed the door. "Are you okay?" I asked Susanne.

"Yes -- they didn't touch me," she replied. "Are you okay?"

"I'm a little bruised, I think. I think I was kicked. I got hit by something in my left thigh before getting my foot kicked from under me. I don't know; maybe he hit me with the rifle."

"What are they going to do with him?" Susanne asked, looking over at Berzan.

A moment or two later Berzan was allowed to open the front door of the car in order to retrieve his keys. Apparently they wanted to search the trunk. Berzan leaned inside to pull out the keys and simultaneously handed Susanne the Sivan Perwer tape from the stereo.

"Put them in, in...." he said quickly, pointing to the glove box. Berzan closed the door and began arguing with the cops again as Susanne stashed his tape.

Ages seemed to pass as the argument continued, though in truth it may have been no more than 30 seconds. Berzan and the second policeman then called over to us, asking me and Susanne to get out of the car yet again. Unlike my first exit, this time I was allowed to step out on my own accord and walk towards them. As the first cop stared at me coldly, the second cop reached into the front seat of the police car and pulled out a two-liter bottle, holding it up towards me.

"No thanks," I said first in English. "Hayir, Memur Bey, tesekkürler."

The first cop began to speak to me in Turkish angrily, then pointed to Berzan, hollering out English, "Who is he?"

The second cop, now holding a liter of water, added, "How do you know this man?"

Turkish words raced through my head as I tried to organize a thought. How could I explain that Berzan was the manager of our hotel and had been recommended to us? Should I say we knew him well or not? What would get us out of this?

Berzan took the bottle out of the second cop's hand, giving it to me. "Drink this," he said, possibly stalling for time to give me a moment to think. "They want to know how you know me. They say I am taking you somewhere against your will. Tell them you know me."

"Friend!" Susanne said anxiously. "How do you say friend in Turkish?!?"

"Arkadas!" I blurted out, finally understanding what to say. "Berzan -- bizim arkadas! Bizim sofor bey! Oteli Ipek Yolu. Arkadas!" Susanne was joining in at this point, saying friend and Arkadas repeatedly.

"This man is a problem!" the angry first cop replied in broken English, his cold blue eyes staring right at me. "He is a problem, a Kurdish problem...." The policeman seemed intent on having us say something -- anything -- that would give them the excuse to drag Berzan away.

"Yok!" I said back to him indignantly. "No problem.... Dert degil! Bizim arkadas!"

"Why are you here today?" the second policeman asked.

"Dogubeyazit," I replied. "Ishak Pasa Sarayi. Berzan -- Berzan sofor bey. Oteli Ipek Yolu'dun! Arkadas!"

At this point the second policeman began to nod his head. "Okay, okay," he said.

Berzan then spoke up again. "They want you to get back in the car," he said. "Take the water with you."

Once again Susanne and I returned to the car, wondering what would happen next. From what we could tell the situation was beginning to simmer down. The cops knew they weren't going to get anything useful out of us. One of them got back into their car to turn it around while the other one continued to argue with Berzan. Once the car was facing the other direction, the second one returned to the car, leaving Berzan to lean into their window and continue the argument, almost as if he was the cop who had just pulled them over. They had let him go, though Berzan was doing his best to give them a piece of his mind before they departed. A moment or two later the police drove off, leaving Berzan near the side of the road.

Berzan returned to the car and slammed the door shut. A pause.

"Bastards!" he yelled, clearly shaken from the experience.

"Are you okay?" Susanne asked.

"They say I take you where you don't want to go," he replied, his English beginning to suffer from his anger. "They wanted to know if you know me. 'Of course they know me. We are together for three days -- friends!' They said we ran the road block. What road block? They said they saw two tourists with Kurdish man and it looked suspicious. They said they fired three shots above us and we didn't stop."

"I thought I heard a tire pop," Susanne responded, reviewing the events prior to being pulled over. "That must have been it. That popping sound."

"I also thought we had a flat," Berzan continued. "That's why I slowed down. Then I saw the police and the man hanging out the window with the gun."

"I honestly didn't know what the hell was going on," I said. "Driving with the windows open there's a lot of noise back here, so I couldn't hear anything. I had no idea there were police behind us until we almost made a complete stop."

"They wanted to take me away and leave you here," Berzan continued, now getting angrier. "Or maybe they would have taken you. They would say nice things to get you to go.... They take you away and 'play football' with you, you understand? They worry that journalists will come here and show what they really do to us..."

"I cannot tell you what they do, what they do to us," he trailed off. "The things they do, the electric... I cannot tell you." Susanne and I could only stare in silence.

"Every day it happens," Berzan continued. "Any day 10 or 15 Kurds are taken off the mountains and they are killed. Nobody knows, nobody knows. This is how we live...."

"I am so sorry," Susanne said, filling in the words that would not come to me.

"You are not used to this," Berzan replied, shaking his head. "They do this to me. They can take me and hit me but I would not let them leave you on the road. Maybe they would have let you drive to Van and maybe I would have to meet you later."

"We wouldn't have left you," Susanne promised him. "If they put you in their car we would have gone with you too."

"The police," Berzan continued, "when they let us go they said they would come by my hotel and would make me treat them well. Free drinks, free rooms, a good time. I said okay. But if they come I will pretend I don't know them. They can only come as civilians, so I will treat them as civilians."

"I'm so sorry," Susanne said. "I wish you could get on a plane with us."

"So this has never happened to you before," Berzan joked as he began to calm down.

"Nope," I replied. "I can't say that it has."

"Now you have," Berzan said, a smirk forming on his face. "It's good for you..."

We sat quietly until nearing the next military checkpoint. As we pulled into the checkpoint, Berzan cranked up his Sivan Perwer tape for one last moment, then turned it off. Berzan continued to sing the Kurdish anthem until rolling down the window to speak with the soldier. The soldier examined our passports courteously and soon waved us through.

"So how are you?" Berzan asked, checking in on us.

"Fine," Susanne replied. "And you?"

"No problem... No problem...."

|

| Muradiye Falls, Turkish Kurdistan |

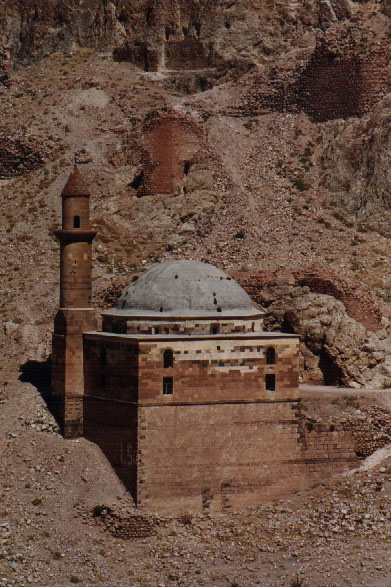

Around 3pm we arrived a Muradiye Falls, a picturesque waterfall just northeast of Lake Van. Just across from the falls was a small cafe which could only be reached by crossing a hanging wood bridge suspended over the Muradiye River. I walked over the bridge slowly, knowing that every step I took made the entire bridge oscillate. Susanne and Berzan, just behind me, took the opposite approach, stepping as powerfully as possible in order to get the length of the bridge bouncing up and down.

"Now we walk like drunks," Berzan smiled, hobbling across the bridge.

The cafe sat on a steep hill just across from the falls. A large group of soldiers were finishing their drinks at one of the tables. As soon as I saw them I felt a shock in the back of my head, as if I had just been startled. It was almost as if I thought one of these young soldiers having a drink was going to come up to me and continue the harassment we had encountered near Mount Ararat. Of course nothing happened; I don't think any of them even noticed me. But I still felt their secret gaze over me. It didn't matter that we had been harassed by civilian police, for in my mind they were all the same -- they were the men with guns. I could only recall two images from that whole encounter: the blue eyes of the policeman who pulled me out of the car, and his gun. Those policemen were probably 80 kilometers north of us now, having a cigarette by the side of the road, but I felt their presence here in the form of these off-duty privates. I might never look at a soldier the same way again.

Berzan sat down at a table with the cafe owner while Susanne and I descended the hillside in order to get the best view of the falls. Because we were visiting in the dry season we weren't treated to the full waterfall experience. Nonetheless the sight of the water gracefully drifting over the cliffs was quite beautiful. It felt strange being surrounded suddenly by such serenity after having gone through such a scary experience with the police less than an hour before.

"Are you okay?" Susanne asked me, staring towards the falls.

"I'm okay," I replied, "Just a little pissed off. I'm just wondering when the shock of all of this will hit me...."

I climbed back up towards the cafe, where Berzan continued to sit at a table having a cigarette with the cafe owner. We did our best to relax over a couple of Cokes while Berzan and his friend chatted and swapped stories in Kurdish. As I finished my soda the soldiers paid their bill and left the cafe, walking over the foot bridge. The irrational side of me felt a palpable relief as they departed -- another encounter averted. The rational side of me smiled as I watched one soldier make his way across the swaying bridge, holding on for dear life as if his next step would be his last.

Berzan put out his cigarette and said goodbye to his friend. We returned to the car and finished our drive to Van in about 45 minutes. Berzan rolled down his window, playing a Ciwan Haco tape as we entered town.

"We would love to bring home some Kurdish music with us," Susanne said. "Are we allowed to buy it legally?"

"Yes, it's legal now," Berzan replied. "Before you leave for Istanbul we will stop at a store and find you some good Kurdish tapes."

Back at the hotel we relaxed on a couch over tea, comparing Berzan's license with our passports. Berzan looked like such a boy in the photograph -- he actually looked his age. In real life, Berzan seemed so much older. No wonder, considering what we had just experienced today -- imagine having to live under the yoke of another people, always under suspicion, always assumed guilty? Kurdistan makes for shorter childhoods, I suppose.

After resting in our rooms for a couple hours we decided to take Berzan to dinner at Merkezi Et Lokantasi. We met him in his office downstairs, which was decorated with photographs of Kurdish children. Behind his desk I noticed a long stringed instrument -- a saz.

"I will play it for you after dinner, if you would like," Berzan offered.

Never in a rush to proceed anywhere without first drinking tea, we sat for a while in his office, watching the evening news in Turkish.

"Is there Kurdish language television here?" I asked.

"Not legally," he replied. "We watch Kurdish TV on satellite. It is called Medya TV. It is illegal in Turkey but everyone watches it on their satellite dishes. I think it is based in Britain, maybe Germany. It has to change names and locations sometimes to keep the Turks from shutting it down."

Berzan shut off the TV as we got ready to depart for dinner. I commented on how difficult it must be to have only the Turkish perspective on television and in the news. "In America we hear very little about what's going on in Kurdistan. We read about it when Turkey goes after PKK fighters in Iraq, but that's about it. We don't hear much otherwise, except when the Turkish government is doing something."

"No one knows what we go through here," Berzan replied. "You only hear about the Kurds as terrorists, the Kurds as killers.... But we have no human rights -- there is no human rights in Kurdistan. You, you can go where you want. I cannot leave Turkey. I cannot leave Van without permission."

"They say Ocalan is only a terrorist," he said, putting out his cigarette. "They don't understand. To the people, his is more real than God."

We arrived at Merkezi Et Lokantasi just after 8:30pm. It wasn't as crowded as it had been two nights earlier, which made for a quieter dinner. Susanne and I both ordered chicken sis kebap and lamb çop sis kebap. Berzan ordered a large plate of lamb kebap as well as several plates of shepherd's salad, cacik and spicy tomato puree. We also received a plate of çig köfte, the raw meatballs that had shocked us during our first meal here. Always willing to make the same mistake twice, I scooped up a meatball and ate it. Susanne was more upfront about it: "You know," she said, "I don't think our stomachs will be able to handle this twice."

"We will have to hide them," Berzan joked. "We would not want them to think we don't like them."

The three of us stuffed ourselves as we spent the evening talking about crime and punishment. Berzan had read about the recent school shootings in America and was interested in how common they were. This led to the interesting topic of blood vendettas.

"In Kurdistan if you kill someone, the dead man's family will want justice," he explained. "They will then kill someone in your family, which will mean your family will want to kill someone again. It is all very bad. Does this happen in America?"

"Not often anymore," I replied. "There are legends of some families going to war with other families long ago, like the Hatfields and McCoys, but now the government punishes people for killing people."

"Does your government always execute killers?" Berzan asked.

"No, not always," I explained. "For example, if I killed someone in Washington DC, I would go to jail for life but not be executed. But if I killed someone in Virginia, just across from DC, I could be sentenced to death. It depends on which state you are in. Whatever you do, though, don't kill anyone in Texas."

After finishing our meals and paying the bill -- $12 for everything -- we returned to the hotel to listen to Berzan play his saz. He brought us to what he called a "traditional Kurdish room," which was decorated with carpets and oversize cushions. As we sipped another round of tea, Berzan asked us questions about American music and what styles were popular regionally. Berzan played several songs on his saz, which he had been studying for about a year. The saz was very unusual to the ears, tuned in such a way that made everything sound extremely dissonant and out-of-tune. Berzan passed the saz over to me, allowing me to play with it.

"Are you sure this thing is tuned right?" I asked jokingly.

"It is tuned right," he replied. "It sounds very good, doesn't it?"

Putting my guitar-playing skills to use I managed to figure out the basics of the instrument but had a difficult time in making anything good come out of it. Unlike the guitar, which is tuned to a 12-tone scale, Berzan's saz was tuned to a seven-tone scale, with some of the frets aligned to be purposely sharp or flat. Using my empty tea glass as a slide, I laid the saz in my lap and played a couple of Led Zeppelin tunes before making a feeble attempt at the Doors song "The End." Berzan showed me how to play a Kurdish song by tapping his fingers over the frets, allowing me to follow each tap.

After returning the saz to Berzan, our conversation shifted back towards politics. "It's very bad what's going on here," he lamented. "Everyone thinks we're terrorists. Everyone is afraid to talk...."

I was surprised by Berzan's openness -- only two days earlier I couldn't even get him to talk about using Kurdish in public. Perhaps our altercation with the police earlier today had been the test that graduated us to a new level of honesty. We had experienced the absurdity of modern Kurdistan for ourselves, so now we could talk about it.

"It's very bad how they treat us," Berzan continued. "We have no rights. They treat us like animals."

"I wish you could come to America with us," Susanne replied.

"It would be a dream," Berzan said quietly, stirring his tea.

The room went silent for a few moments. A grin then appeared on Berzan's face. "Bashka!" he proclaimed.

"What does that mean?" Susanne asked.

"It is Turkish.... You say it when there is a pause in conversation and you don't know what to say. In Kurdish we can also say eysha."

"I don't think we have a word for that in English," I replied.

"You could say 'Well!'," Susanne suggested. "Or 'So!'"

"Bashka!" I said, practicing aloud.

I glanced at my watch and noticed it was well past one in the morning. Berzan's bashka couldn't have come at a better time, for I was becoming extremely tired. But I was quite glad his invitation to hear him play his saz had turned into a long evening over tea.

"Despite what happened today," Susanne said as we were going to bed, "I'm so glad we spent the last three days with Berzan. There's no way we would have been able to hang out with someone like that if we had joined a tour."

"There's a lot we wouldn't have experienced in Kurdistan if we had gone on a tour," I replied.

"I can't believe we're going back to Istanbul tomorrow," Susanne said, shutting out the light.

Bashka, I thought to myself.

The next morning, Berzan brought us to the Van airport for our flight back to Istanbul. We spent three final days in the city, revisiting our favorite sites, lounging in cafes and even experiencing a traditional Turkish bath. But emotionally, our trip to Turkey had concluded in Van. We had crossed the length of this beautiful, enticing country by land in two weeks. Our Anatolian fortnight had come to an end.

checkpoint about two minutes after leaving the accident scene. Berzan rolled down his window and began speaking rather authoritatively to a young soldier while Susanne and I each tried to piece together what had happened. My first impression was that the old man was carrying cattle in his truck and it had overturned, but now that I had time to think about it I wasn't really sure. Meanwhile, the soldier waved us through without asking questions as he got on his walkie talkie to radio for assistance. A great smuggling strategy, I thought to myself cynically. Tell the soldiers there's been an accident and speed through the checkpoint while they're preoccupied.

checkpoint about two minutes after leaving the accident scene. Berzan rolled down his window and began speaking rather authoritatively to a young soldier while Susanne and I each tried to piece together what had happened. My first impression was that the old man was carrying cattle in his truck and it had overturned, but now that I had time to think about it I wasn't really sure. Meanwhile, the soldier waved us through without asking questions as he got on his walkie talkie to radio for assistance. A great smuggling strategy, I thought to myself cynically. Tell the soldiers there's been an accident and speed through the checkpoint while they're preoccupied. where we drank tea and ate scones as classic Hanna Barbera cartoons played on a TV in the corner. Not far above our heads we noticed an ink-drawn caricature of Gary Coleman.

where we drank tea and ate scones as classic Hanna Barbera cartoons played on a TV in the corner. Not far above our heads we noticed an ink-drawn caricature of Gary Coleman.