|

12th century Seljuk gate of the

Karatay Han Caravanserai, near Kayseri |

Friday, September 3.

After checking out of the Ufuk Hotel and eating a quick breakfast at the Sultan Restaurant, Susanne and I walked over to Ötüken Tours to meet our minibus. The agent we met at there yesterday introduced us to Özcan (pronounced Erzjen), who would serve as our guide for the next two days. Özcan was a small man in his late twenties with thick, black hair and a thin face. We were then joined by Michael and Maggie, a British couple in their thirties who had just been on holiday along the Turkish Aegean. The five of us introduced ourselves to each other in a big circle. When Özcan heard Susanne's name, he gave her a big smile and said, "Susanne is a Turkish name, you know. My sister is named Susanne, too."

Climbing into the minibus, Özcan introduced us to Ali, a broad-shouldered young man with a round face who would serve as our driver. Ali didn't speak much English but he had a confident smile on his face. Inside his van there were numerous air fresheners dangling from his rearview mirror, including a cartoon of Tweety Bird and a No Smoking sign with the words "except for driver" scribbled in pen across it. After getting settled in the van, the six of us soon drove out of Göreme, leaving behind the picturesque villages and mesmerizing fairy chimneys of Cappadokia we had gotten to know so well.

As we drove along the highway towards Kayseri, the largest and easternmost city in Cappadokia, Özcan explained our itinerary for the next two days. "We have a lot of driving today," he said in a soft voice, "but we will stop several times at interesting places along the way. In less than an hour we will visit the Karatay Han Caravanserai, one of the main stops along the Anatolian Silk Road. Soon after that we will have a tea break. In the afternoon we will have lunch, and around four o'clock, you will get to taste our famous Turkish ice cream. Do you know about Turkish ice cream?"

one of the main stops along the Anatolian Silk Road. Soon after that we will have a tea break. In the afternoon we will have lunch, and around four o'clock, you will get to taste our famous Turkish ice cream. Do you know about Turkish ice cream?"

"I hear it's very thick," I said. "Very gummy."

"Yes, it is thick, but I would not call it gummy," Özcan replied. "It is so thick you will need a fork and knife to eat it. The first time I tried it as a boy I remember sitting down at a table, and someone gave us a fork and knife. I said to the waiter, 'But I am having ice cream -- I will need a spoon.' The waiter replied, 'No, you will need a fork and knife.' When the ice cream came I could not believe it. The only way I could eat it was to cut it with the knife! But it is also very smooth -- the ice cream will melt in your mouth. I promise you will enjoy it."

"What makes it so thick?" I asked.

"It's a secret recipe from the town of Karahmanmaras," Özcan replied. "I do not know how they make it. But you will get to taste it in Karahmanmaras, in the restaurant that is most famous for serving it."

"What time will we arrive at Nemrut tonight?" Michael asked.

"Around sunset," Özcan answered. "We will stay in Kahta, the town that is closest to Nemrut Mountain. We will then get dinner along Atatürk Dam and go to bed early, since we will have to wake up before 3am in order to reach Nemrut for sunrise."

|

Anatolian Trivia

Kayseri, which in Roman times was known as Caeseria, was once the home of St. Gregory the Illuminator. Raised and educated in Caeseria during the second half of the 3rd century AD, St. Gregory brought Christianity to Armenia, becoming its first bishop and making it the first nation to adopt the faith as the state religion.

|

Not long after exiting Kayseri we arrived at the Karatay Han Caravanserai. ("Karatay Han" means "The Black Foal Inn" in Turkish.) Like the caravanserai we had visited two days earlier, Karatay Han was a 13th-century citadel that looked more like a fortress than an inn. Despite the fact that Karatay Han is one of the best preserved Seljuk caravanserais in Turkey, it isn't a major tourist attraction. After Ali parked our minibus, Özcan jumped out an went in search for the gatekeeper. The caravanserai was locked most of the day so we would need to find someone to let us inside.

caravanserais in Turkey, it isn't a major tourist attraction. After Ali parked our minibus, Özcan jumped out an went in search for the gatekeeper. The caravanserai was locked most of the day so we would need to find someone to let us inside.

Among a group of teenaged men hanging out in front we found the gatekeeper, who produced a long metal key that unlocked Karatay Han's massive wooden doors. The teenagers followed us inside as Ali smoked a cigarette by the minibus.

"Karatay Han was a very important stop along the Silk Road," Özcan explained as we entered the main courtyard. "When caravans stopped here, they could feed their horses, buy and sell goods, even visit a doctor. We know today that there was a doctor here because if you look on the wall you can see two serpents with wings, the symbol of physicians since Roman times. I do not remember what it is called in English, though."

"It's a caduceus," I said.

"Yes, the caduceus," Özcan replied. "You can also see the 12 signs of the zodiac on the wall. It was important to have a zodiac for travelers here, since many traders were superstitious."

Özcan led us into a small room in a dark corner of the courtyard. "Here is the hamam, the Turkish bath. Today it is dusty and dirty, but 600 years ago you would have seen a hamam that looks much like the hamams of today. A fire and boiling water was kept under the marble floor, which would heat up the room and make the bather sweat. They could then wash and cool off with colder water from a basin."

Back in the sunny courtyard we walked over to a hole in the ground covered with a metal grate. "This is the cistern," Özcan explained. "Enough water could be kept inside it to feed all the people and horses staying at the inn. The water was collected from the roof, and then would go down pipes into the cistern. They covered the top of the cistern several years ago after a tourist fell in and was hurt very badly. If you drop a rock inside you will hear that it is a very big drop."

|

| Inner courtyard of the Karatay Han caravanserai |

To the left of the courtyard we found the caravanserai's stables. Much like the last caravanserai we visited, Karatay Han's stable was a soaring vaulted space of tremendous echoes, with dozens of pigeons in the rafters. We then heard what sounded like a hissing sound from the back of the room. Özcan made a similar sound to see if he could figure out what was causing it. "I think it's a snake," he said. "Let's not bother it."

Just outside the stable I spotted a young boy sitting on a thin stone staircase leading to the roof. "Merhaba," I said to him, waving.

The boy didn't respond at first but his grandmother, who was sitting at the bottom of the steps, prodded him a bit to wave back.

"Merhaba," he replied.

he replied.

Neither Susanne nor I felt we had photographed enough children on this trip, so I asked the grandmother if it was okay to take a picture of him. "Fotograf çekebilirmiyim?" I asked.

I asked.

"Yok," the grandmother said firmly, raising her head up. Another Kodak moment lost to the djinns of the Silk Road.

the grandmother said firmly, raising her head up. Another Kodak moment lost to the djinns of the Silk Road.

As Özcan returned outside to share a smoke with Ali, the rest of us climbed up the stone staircase to the roof. From up top we had a good view of the small concrete homes in the surrounding neighborhood, with fields of evenly spaced poplar trees shading the land in the distance. A woman who was hanging close out to drying from another rooftop smiled and waved at us.

We walked along the roof, which was designed as a series of stout arches interlaced with rows of flat marble. From a distance it looked as if giant speed bumps had been placed precariously close together. I wasn't particularly sure of the reason for this architectural design, but Michael chimed in with a plausible theory.

"It looks like there are drains placed along the wall in certain places," he observed. "When it rains the water would collect atop the flat spots, pooling between the raised arches."

"I think you're right," I replied. "And depending on how high the drainage system was from the floor, they could regulate how much water went down in the cistern and how much water was stored up here. Amazing...."

|

| Roof of the Karatay Han caravanserai |

After descending the marble steps, Susanne and I both went outside to get a photo of the caravanserai. There was plenty of room for us to back up and get a shot of the whole structure but Ali had parked the minibus smack in front of the gate. We asked Özcan if there was a way we could move the bus. Özcan tapped Ali on the shoulder and explained our request in Turkish. Ali smiled and stomped out his cigarette before driving the bus across the parking lot.

After spending another hour on the highway, Özcan asked if we'd like to stop and get some tea. It was just before noon -- a little early for lunch in Turkey, but a perfect time for some çay and a bathroom break. Özcan brought us to a whitewashed restaurant with outside tables atop a raised arcade connected to an interior dining room. Michael, Maggie, Susanne and I all had apple teas and snacked on some breadsticks as we talked about our vacations and some of the places we'd visited in the last week.

|

Turkish Pronunciation

Interested in learning how to pronounce the Turkish words mentioned in this journal? Check out my Turkish pronunication guide!

|

At one point Susanne needed to use the restroom so she asked a waiter in Turkish: "Tuvalet var mi?" The waiter stared at her, completely puzzled. I tried repeating the question and got the same blank response.

Özcan overheard us and came over to our table. "What are you trying to ask?"

"Is there a toilet here?" I replied.

"Tuwalet!," Özcan laughed, pronouncing the V in tuvalet like a W. "No one in this part of Turkey says tuvalet with a V. And you need to have your voice go up when you ask the question. Try it again."

"Tuwalet var mi?" I said, making the "var mi" go up like I was asking a question in American English. The waiter and Özcan gave us a big grin and pointed downstairs. Susanne quickly got up and followed their directions.

"Orada, degil mi?" I asked, which essentially meant "Over there, is it?"

"Var," Özcan replied with a smile. "So you know more Turkish than 'Tuwalet var mi?'"

Özcan replied with a smile. "So you know more Turkish than 'Tuwalet var mi?'"

"Barely."

"At least you now know how to say what is most important," he joked.

After Susanne returned from the bathroom, Michael and I made a quick run to the men's room. Just outside the bathrooms was a large marble water fountain with half a dozen carp swimming in it. "In lieu of Abraham's Pool," I said to Michael, referring to the pilgrimage site we'd visit in Urfa that's known for its thousands of carp.

Back in the minibus we drove for another two hours. We killed time by getting to know Özcan, who we discovered through his taste in radio stations was a big fan of Whitney Houston ballads. (While I didn't want to be rude and complain, Ali made no bones about it and constantly tried changing the radio station to more traditional Turkish folk music, which I enjoyed immensely.)

"My family is from Trabzon, on the Black Sea," Özcan said. "I am Laz, you know. Do you know of the Laz people?"

"Not really," I said, to my embarrassment. I vaguely remembered reading about the Laz as an ethnic minority in northeast Anatolia but didn't know much beyond that.

"We live on the Black Sea and in the valleys near Georgia," Özcan explained. "We consider ourselves Turks, but some people like to make jokes about Laz. Even though I am Laz it doesn't bother me. Sometimes the jokes are very funny."

"Like what?" Susanne asked.

Özcan took out a piece a paper and drew a straight line. "What do you call this?" he asked.

"I don't know," Susanne said as I tried to anticipate the punch line.

"A Laz maze," Özcan replied dryly.

"That's terrible," I said, snickering at the same time.

"The jokes are all like that," Özcan said. "They all have to do with the Laz being stupid people. But they can still be funny. It doesn't bother me because I know it's not true."

As Özcan told more jokes, I looked in my Lonely Planet to see if that was where I had read about the Laz. I quickly found a page that summarized the ethnic minorities of the eastern Black Sea region.

"I found it," I said, skimming the paragraphs to summarize what the book said. "The Laz are closely related to ethnic Georgians and they converted from Christianity to Islam when they started to assimilate with Ottoman Turks in the 16th century. The Laz are recognized in Turkey as top-notch fighters, and were well known as the hand-picked body guards of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk."

"Were you in the army?" Maggie asked Özcan.

"Oh yes," he said proudly, without elaborating.

"How about you, Ali?" I asked. Özcan translated the question to him.

"Yes," Ali replied in his thick accent, smiling at me through the rear view mirror. "A good soldier."

Around 1:30pm, while driving along a beautiful green hillside, Ali pulled over the bus below a small building. "We are now in the village of Tekir," Özcan said. "We will stop here for lunch."

Stepping outside we climbed up a stone staircase to a picturesque lunchtime setting: wooden benches shaded under enormous trees, with a small herd of sheep just beyond the benches and a trickling stream running down hill.

"How pastoral, isn't it?" Michael joked.

"Simply bucolic," I replied.

We settled down on a long bench as a waiter came by to give us silverware and napkins. "Would like something to drink?" Özcan asked. "Coke? Beer?

"Cokes would be great," we replied.

"You can get either meat or fish," Özcan continued.

"What kinds?" Susanne asked.

Özcan pointed to the sheep on the hill, then to a cement water tank. "Meat, fish -- this is what they have," he said. Given the choice of mutton or fish that were caught immediately downstream from a herd of sheep, we selected the mutton.

Classic Recipe:

Çoban Salatasi

In order to prepare shepard's salad, you'll need a large cucumber, a bunch of parsley, a firm tomato, a small onion, a couple of lemons and some olive oil. Deseed the cucumber and tomato and chop them finely. Chop up the onion and the parsley. Combine them together in a bowl with a tablespoon of olive oil and the juice of one of the lemons. If you want it to be really tangy, add more juice from the second lemon -- or a few tablespoons of pomegranate juice if you can get it. Season with salt and pepper and toss well. If it seems too dry, you can add a dash of water or lemonade to moisten it. Best is served soon after preparation, but it'll stay good for a few days if refrigerated.

|

The waiter reappeared with our drinks and two large plates of salad which appeared to be made of finely diced tomatoes, onions, cucumbers and parsley. Because of our traditional avoidance of salads when traveling outside the US, Susanne and I initially didn't try the salad. Michael and Maggie, however, wasted no time in scooping some onto their plates.

"This is delicious," Maggie said.

"It's called çoban salatasi -- shepherd's salad," Özcan replied. "It is a very traditional salad. You can find it all over Turkey."

I began to worry I would give offense if I didn't taste it. Susanne and I both looked at each other for a moment then shrugged. I pulled out a bottle of Pepto Bismol and gave her a couple of tablets.

"When in Turkey, I guess," I said as I spooned some salad for myself. To my surprise it was very tasty, despite the fact that I'm not a fan of tabouleh, which was very similar to the salad. Susanne seemed to enjoy it as well.

Two large plates of mutton soon arrived, each hosting a stack of freshly barbecued meat garnished with grilled chili peppers and onions. Though it was sometimes hard to avoid eating gristle, the meat itself had a nice smoky flavor. As the six of us ate, Susanne, Michael and Maggie compared parachuting stories. Though I had never tried it, the three of them had gone on jumps.

"Is parachuting for sport popular in Turkey?" Maggie asked Özcan.

"Not really," he smiled, "But I have jumped over 600 times."

The four of us smiled back at him, but were a bit confused by his answer.

"Really?" Susanne asked.

"He's joking," I jumped in before Özcan could reply, assuming he was messing around with us.

Özcan smiled again and took off a gold ring on his right hand. "I was a helicopter pilot in the army for seven years," he explained, showing us the military academy seal on his ring. "We had to practice as paratroopers. I have made jumps all over Turkey."

I felt really bad that I had assumed Özcan had been joking, but now took serious interest in his experience. "Seven years?" I asked. "Were you an officer?"

"Yes," he replied. "I was in a military program when I was in school, then I entered the army academy. I wanted to be a helicopter pilot, but you couldn't learn to fly if you waited for your conscription. I made the army my career."

"Why did you leave the army?" Susanne asked.

"It was fun, but I wanted to try a new job," Özcan said. "A friend of mine was a tour guide and he helped me become certified. A certified guide can work anywhere in Turkey and make good money. It is also much less scary than jumping out of helicopters."

We finished our lunches with a round of tea. As the four of us sipped from our tulip-shaped glasses, Özcan walked over from inside the restaurant with a small slip of paper. "Mike and Maggie owe me one million lira for your drinks," he said. "Susanne and Andy -- you owe me 800,000 lira." After taking our money, Özcan walked down hill for another cigarette.

for your drinks," he said. "Susanne and Andy -- you owe me 800,000 lira." After taking our money, Özcan walked down hill for another cigarette.

"Weren't all drinks covered in the cost of the tour?" I asked quietly.

"I believe so," Michael responded.

I pulled out the tour pamphlet from my daypack. "Yep, it's right here," I said, mildly annoyed. "Cost includes all meals."

"Maybe meals includes tea and coffee but not sodas," Susanne said.

"It's no big deal if we have to pay," I continued. "But it would be nice to know ahead of time exactly what is included and what isn't. We've been screwed on tours before and I really don't want to get screwed again."

"He seems like a nice enough guy," Susanne responded. "Let's just see how it goes."

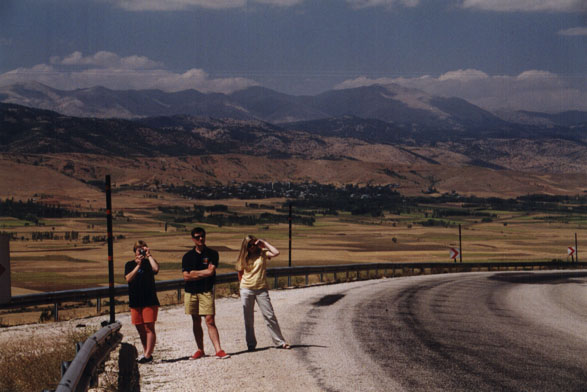

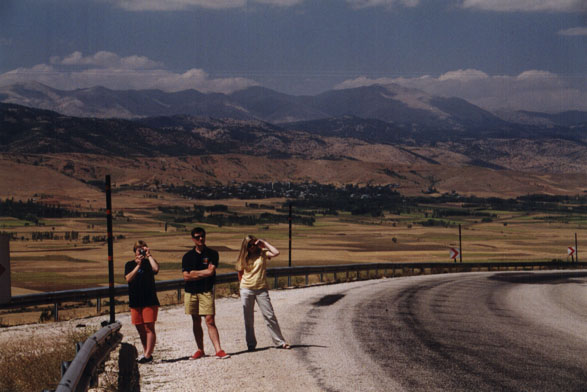

Returning to the minibus we drove for three hours towards Kahramanmaras. Along the way Özcan allowed us to stop briefly on a mountain pass in the Anti Taurus range.

"There are two major mountain ranges in Anatolia," Özcan explained as we stared over a green valley. "In the west you have the Taurus mountains, and here in the east you have the Anti Taurus. As we go east the landscape will change from mountains to flat plains. Tomorrow when we go south of Urfa to Harran, you will see no hills or mountains. We will be in the land of ancient Mesopotamia."

|

Maggie snaps a picture of me as Michael and Susanne hang out on a roadside.

The Anti Taurus mountain range can be seen in the distance. |

By 4pm we arrived at the outskirts of Kahramanmaras (pronounced Kah-rah-MAHN-mah-RAHSH), a city whose name rolls off the tongue like the briefest of Ottoman sonnets. A prosperous, modern city that traces its roots back to Hittite times, Kahramanmaras is notable for two curiosities: the colorful sidecar motorcycles that crowd its streets, and an ice cream so unique and unusual it must be tasted to be believed. As Özcan explained to us earlier, Kahramanmaras dövme dondurma (authentic Kahramanmaras ice cream) is so rich and creamy that it must be eaten with a fork and knife.

As we slowly navigated the congested streets of this mountainside city, I conjectured aloud how the ice cream was made. "I've heard it described as being almost gummy," I said. "I wouldn't be surprised if contains a natural tree gum or resin in it."

"No, no, that's not it at all," Özcan said from the front seat, shaking his head. "It is thick, but not like gum. I do not know how to explain it. You will see for yourself."

"But you don't know how they make it?" Susanne asked.

"No, I don't," he replied. "In the 1800s, when ice cream became popular in Europe, they tried to make it here but it always melted. Up in the caves along the side of the mountain people would make their ice cream; they hoped the caves would keep the ice cream cool for awhile. But it still melted. Only when they found their secret Kahramanmaras recipe did they make it in a way that it would last in the heat."

"I've read that the ice cream is so thick they hang it on meat hooks," I said.

"Yes, it is true," Özcan smiled, "but you would not be able to eat that much of it."

Ali pulled over the minibus along a busy thoroughfare, dropping us outside our destination. The Yasar Pastanesi is Turkey's answer to Ben & Jerry's when it comes to Kahramanmaras ice cream -- in fact, it was the founder of the restaurant who perfected the recipe over a century ago. Even now the restaurant is a relic from a more innocent age. Entering the shop we were quickly surrounded by a throng of waiters going to and fro, each decked out in crisp white uniforms that would have been at home in any 1950's diner. The dark wooden interior of the restaurant was decorated with eclectic fin de siecle Ottoman memorabilia -- a Turkish Bennigan's where the antiques were actually real.

We sat down at a wooden booth with a fine view of old German rifles and Ottoman swords along the wall, and a row of framed photographs of old men standing in front of those famous hunks of ice cream hanging on meat hooks.

"They are all famous Turkish politicians," Özcan said, pointing to the photographs. "Presidents, prime ministers -- they all come to Kahramanmaras for ice cream. It is a tradition."

None of us had to wait for long to sample this mythical mouthwatering treat. A young waiter appeared with a tray of dishes, each holding a square dollop of vanilla ice cream decorated with green pistachios shavings.

"Afiyet olsun!" Özcan said. "Bon appetit!"

|

A sunburnt Susanne relishes her

vanilla Kahramanmaras ice cream |

I picked up my fork and tested the ice cream by trying to cut into it. The fork struggled to slice through the thick dessert. It wasn't as if the ice cream was frozen solid -- it was more akin to a mysterious physical counterforce preventing me from separating a small sample from the vanilla cube. Finishing the job with my knife, as I had been instructed, I popped a sliver of ice cream into my mouth. I now understood why Özcan had struggled to explain this mysterious substance. Neither solid nor liquid, the legendary Kahramanmaras dövme dondurma was a unique physical state in its own right. The creamy vanilla melted in my mouth like white chocolate, yet I actually had to chew the ice cream to finish it off. As Özcan had insisted, the ice cream wasn't chewy; it was just indescribably thick. Unnaturally thick. Perplexingly thick. Yet thoroughly addictive. None of us knew how to explain the sensation of eating the Kahramanmaras ice cream except to say that we had never experienced anything like it.

"I can't believe this hasn't caught on in the US," Susanne said as she licked off some pistachio shavings from a forkful of ice cream.

"They have just opened a restaurant in London," Özcan replied, knowing that he had us hooked on the stuff. "If it is in London maybe it will soon be in New York as well."

I could only hope he was right. Granted, I imagined the ingredients that went into making this rich ice cream would make even Paul Prudhomme squirm with caloric embarrassment. Nonetheless, as I finished off my last sliver of Kahramanmaras heaven I wondered how long it would be before I could experience the same epicurean sensation at home in America.

After finishing our ice creams we waited a few minutes for Ali to get the minibus, which he had apparently parked illegally in a no-parking zone and was on the verge of getting a ticket. Ali reappeared the minibus, smiling as always, with a large bag of pistachios to share with us.

"Would you like some nuts?" Özcan offered as we left the city limits.

The four of us each took a small handful and began peeling the shells. Unlike the pistachios I had sampled during our Ilhara Gorge walk, these were perfectly ripe and ready for snacking, despite being unroasted. The green shells were a bit difficult to crack, but if you bit them at the right angle you could reveal the meaty pink pistachio flesh.

"In Turkish they are called fistik?" I asked.

"Yes, fistik," Özcan replied. "Turkey is famous around the world for pistachios, but the pistachios from the region between Kahramanmaras and Gaziantep are famous right here in Turkey. They are the very best."

We had less than a couple hours' drive to Kahta, the dreary oil town that would serve as our base for reaching Nemrut Dagi tomorrow morning. There was little worth noting as we crossed the rolling countryside except the endless groves of olive and fig trees. We did, however, pass an old man dressed like a crossing guard, imploring us to drive slowly as we made a sharp curve around a hillside.

"His entire family was killed here many years ago," Özcan explained. "He was driving too fast, and they all died in a crash. He was the only one who lived. He has since dedicated his life to standing in front of the curve, reminding drivers to slow down."

Just after sunset, our minibus arrived in Kahta. There was desperately little to see in this dusty town -- its one major street was lined with auto repair shops and the occasional motel. Anatolian paradise this wasn't, but Kahta was the most convenient spot from which to begin a trip up Mount Nimrod, better known as Nemrut Dagi. Nemrut was world famous for its mysterious giant stone heads, propped atop the mountain by a megalomaniac Greek king 2000 years ago. By the time we would see the sun again tomorrow, we would be standing atop this mountain, gazing at these legendary statues.

For now, though, we had to settle down for the night. Özcan brought us to the Otel Mezopotamya, which had been described in the Lonely Planet as a new hotel. While the building's incarnation as a hotel might be new, the structure itself was long past its prime. Creaking floor boards, peeling paint, hissing incandescent light bulbs -- these were the amenities of the "new" Otel Mezopotamya. Despite is shortcomings, the hotel seemed like a perfectly acceptable place to spend a short night.

Özcan gave us an hour to shower and rest before going out for dinner. Around 7pm Susanne and I returned to the Mezopotamya's modest lobby, where we found Michael and Maggie flipping through some local travel literature. Özcan and Ali were speaking Turkish with a man whose sandy hair, round face and thick mustache would have made him at home in Warsaw or Moscow.

"Hello again," Özcan said to Susanne and me as he saw us make our way down the stairs. "This is Arkin; he will drive for us tomorrow morning. Today was a long day for Ali so we will let him sleep in tomorrow."

"Long day, yes," Ali said, catching Özcan's words in English.

Arkin, the man with the Slavic features, stood up and shook my hand with a firm, vise-like grip that reminded me of my grandfather's.

"Merhaba, merhaba," he said, his intimidating, deep voice betrayed by his enormous smile.

he said, his intimidating, deep voice betrayed by his enormous smile.

"Merhaba," I replied. "Nasilsiniz?"

"Good, good," Arkin answered in English.

The seven of us piled back into the minibus and drove down Kahta's main road. Özcan pointed to a bright light, high in the distant sky. "Do you see the light on that telephone tower?" he asked. "That is on Mount Nemrut. Tomorrow you will be up there."

Ali drove us to the opposite end of town to the Akropolian, a popular restaurant known for its daytime views of the lake formed by Atatürk Dam. At night all we could see was a faint shimmer of light reflecting from beyond the restaurant. If the reflection hadn't been shimmering the whole area could have simply been an empty field for all I could tell.

We sat on a second floor patio and enjoyed a long dinner. Maggie and Mike both ordered adana kebap, which I too would have enjoyed if I hadn't worried so much about catching some terrifying Mesopotamian microbe. Having seen the stacks of raw meat sitting behind a glass counter as we entered the restaurant, my stomach had made up my mind for me. Susanne and I both ordered Turkish pizza. The meal also included a hefty portion of shepherd's salads, yogurt, and enormous pieces of tandoor flat bread that must have been about three feet long.

"This is traditional Turkish bread," Özcan said. "Today you rarely find it served like this in restaurants, but we still make large breads at home."

Before returning to the hotel, Özcan allowed us to stop at a small grocery store to pick up supplies for the next morning. We would be getting up at 3am yet wouldn't have breakfast until 9am; if we wanted any snacks for our ascent of Nemrut Dagi we needed to buy them beforehand. Along with several boxes of juice, Susanne and I purchased a banana, some wafers and a small piece of fruitcake.

Susanne also pointed out a green fly swatter shaped like a maple leaf. "I wish we'd had that in Cappadokia," I said.

"So let's buy it," she replied.

"Are you serious?" I asked.

"Why not?" she said. "We keep saying we wish we had a fly swatter, so let's buy one." After spending 700,000 lira, the two of us were well armed with rations and weapons for our early morning ascent.

the two of us were well armed with rations and weapons for our early morning ascent.

Back at the hotel, Özcan walked upstairs with us and explained our schedule for the next morning. "I will wake you up at 2:45am, and we will leave soon after 3am. That will give us time to climb to Mount Nemrut for sunrise. We will visit some Greek and Roman ruins on the way back to the hotel, get breakfast, and then drive south for Urfa. It will be a long day, so sleep well."

"Should we bring blankets for the climb?" I asked.

"We will bring blankets, but I will supply them," he replied. "Leave your blankets in your room."

"Sleep well," Özcan said as we reached our hotel room door. "See you in four hours."

one of the main stops along the Anatolian Silk Road. Soon after that we will have a tea break. In the afternoon we will have lunch, and around four o'clock, you will get to taste our famous Turkish ice cream. Do you know about Turkish ice cream?"

one of the main stops along the Anatolian Silk Road. Soon after that we will have a tea break. In the afternoon we will have lunch, and around four o'clock, you will get to taste our famous Turkish ice cream. Do you know about Turkish ice cream?" caravanserais in Turkey, it isn't a major tourist attraction. After Ali parked our minibus, Özcan jumped out an went in search for the gatekeeper. The caravanserai was locked most of the day so we would need to find someone to let us inside.

caravanserais in Turkey, it isn't a major tourist attraction. After Ali parked our minibus, Özcan jumped out an went in search for the gatekeeper. The caravanserai was locked most of the day so we would need to find someone to let us inside.