|

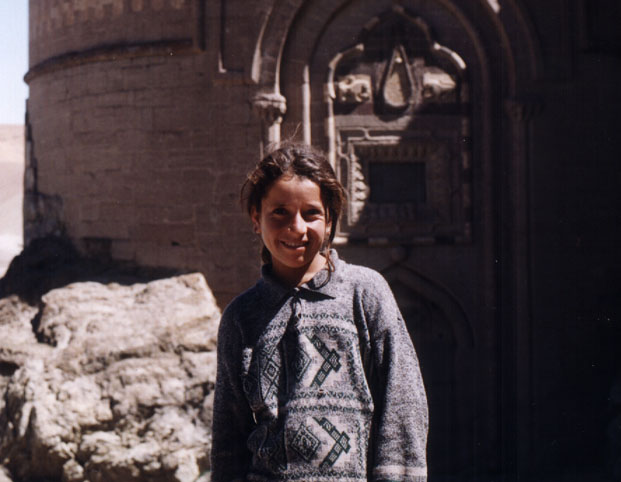

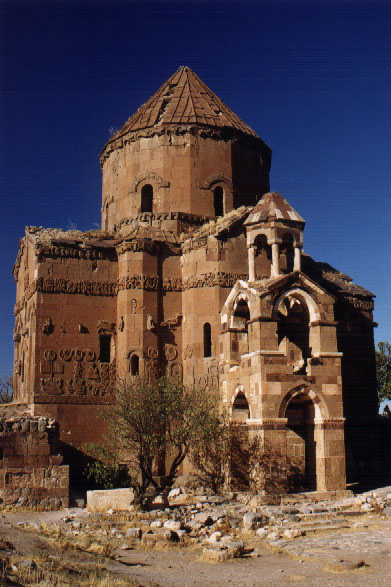

| 10th century Armenian Church, on Lake Van's Akdamar Island |

I may or may not have slept for a couple of hours -- I was too groggy to know the difference. The rising sun was still hidden behind a range of jagged, graphite-gray mountains to the east, though the sky had brightened to a crisp morning blue. Most of the other passengers of the bus, including Susanne, were still asleep save a thin Kurdish man in his thirties who was vomiting in a thick plastic bag dutifully provided by the yardimci.

The bus entered a sizable town steeped in the bottom of a jagged gorge. Men on motorscooters steered around us as we pulled over to a Best Van office. High above on the left side, the ruins of a Seljuk

As our bus drove northeast beyond the gorge, the terrain transformed into a wide valley, revealing gravel-colored hills on all sides, with more mountains further afield. Descending the far side of a pass I saw an expanse of blue trailing far off towards the north, a mountain perched along its western shore. We had finally reached Van Gölu -- Lake Van. The first thought that entered my mind was an image of the approach to Copacabana, a Bolivian town along the edge of Lake Titicaca which Susanne and had visited precisely one year before.

As my sleep-deprived mind continued to clear, I remembered we were far, far away from that Andean lake. Yet as we approached the shore I could see that Lake Van shared Titicaca's mysterious, deep blue hue, with only the reflections of passing clouds blurring its near-perfect complexion. Along with its gorgeous color, Lake Van is perhaps best known for a rare quality it shares with another great body of water, the Dead Sea: extreme salinity. Millions of years ago, an enormous eruption from the volcano known as Nemrut Dagi (not to be confused with the other Nemrut Dagi we visited two days earlier) blocked the outflow of Lake Van's only river, causing the lake to bloat up with mineral-rich water from the mountains. With no river to release its waters, Van maintains its size through evaporation, leaving the lake saturated with unusual amounts of minerals and natural sodas. The lake is so rich with minerals that its waters are extremely buoyant, causing swimmers to float uncontrollably -- not unlike the waters of the Dead Sea. This mineral saturation also allows the local Kurds to wash their clothes without the need of soap. The lake's chemical content works just as well as any detergent.

We soon passed through the town of Tatvan, 100 kilometers from our destination. Until recently, Tatvan was a booming port whose ferries carried cargo and train cars across the lake to Van before continuing onward into Iran and Iraq. But Turkey's undeclared war on Kurdish separatists dried up the local transport business, leaving many of Tatvan's residents wondering what to do next. The bus dropped off a couple of passengers before continuing towards Van along a two-lane road hugging the shoreline. Susanne began to stir a few minutes later.

"Where are we?" she asked, removing her sleeping blinds from her eyes.

"Along Lake Van," I replied. "Probably another hour or so to go."

The road briefly steered away from the shore, cutting through another mountain pass. As the bus returned to the coast 15 minutes later I noticed a small island several kilometers off the shoreline, shaped like an immense shark fin.

"Arrrrrgh, Shark Fin Island," I joked. "We must be nearing pirate waters, matey...."

As we returned to the water's edge I noticed what appeared to be a rectangular structure with a low, conical roof sitting near the right side of the island. The closer we got the more I recognized it as Lake Van's most famous landmark.

"It's Akdamar Island!," I said to Susanne, tapping her with one hand while grabbing my Lonely Planet with the other. "That has to be Akdamar's Armenian church."

One thousand years ago, centuries before the Ottoman Turks ruled the land, Lake Van was Armenian territory, and Akdamar Island was its spiritual center. At various times over the past 1600 years, Akdamar Island served as the home of the Armenian Orthodox patriarch, the Katholicos. Though most of the island's buildings are gone, its church remains brilliantly intact, perhaps the best preserved medieval Armenian religious structure outside of modern-day Armenia. It was the experience of seeing photos of Akdamar Island that first attracted me to Lake Van; despite my exhaustion I was thrilled to see it with my own eyes, even at a teasing distance. At some point in the coming days we would certainly make our way back to this spot and hopefully charter a boat to the island.

Leaving Akdamar Island behind us, the bus passed through the town of Gevas, best known for a well-preserved Seljuk cemetery. The road once again veered away from the shore, heading several kilometers inland towards Van's outer city limits. Surrounded by an increasing number of apartment blocks and small factories, we soon pulled over at what appeared to be a police checkpoint. A plain-clothes official boarded the bus from the front as several armed soldiers stood guard outside. Row by row, the official checked the identification cards of everyone on board, occasionally referring to a collection of papers kept in his khaki safari vest.

"Pasaportunuz, lütfen,"

"Iyi günler,

He leafed through our passports one page at a time, occasionally looking up at us. After scrutinizing them to his satisfaction he returned the passports to me, nodding his head as he handed them over. Within a few minutes the official departed the bus, allowing us to enter the city and proceed to the otogar.

The bus made its way through the morning traffic, passing a large white statue of a Van cat, a prized local feline famous for its eyes: one is colored yellow while the other is green. I wasn't sure if we would get a chance to see a Van cat during our stay -- the animals have become so valuable that residents are forced to keep them secured inside their homes to avoid potential catnapping, so to speak.

On the north side of town, the bus arrived at the otogar,

Susanne and I didn't have hotel reservations in Van, but various sources on the Internet had recommended the Ipek Yolu Hotel, near the center of town. Once at the hotel, we were encouraged to ask for Mr. Berzan Dersimi if we needed any help in arranging tours of the area. With Turkey's military crackdown on Kurdish terrorists, Van's tourism industry had collapsed almost completely, wiping out any chance of us latching on to a regularly scheduled minibus tour like the ones so prevalent in Cappadokia. Since we both wanted to visit a number of Kurdistan's off-the-beaten-track historical sites, Susanne and I probably would have no choice but to hire a private guide. Assuming the remaining travel agencies couldn't arrange one for us, hopefully Mr. Dersimi could.

The taxi made its way into downtown Van, weaving through a traffic sprawl of cars, motorscooters and horsecarts laden with fresh produce from the countryside. The Ipek Yolu Hotel was right around the corner from the main road, across the street from the Kebapistan restaurant and several banks. Our Lonely Planet guide also mentioned that the tourist information center was a few blocks to the south, assuming it was still in business -- I didn't notice it as we exited the taxi. To our cabbie's chagrin, we didn't have exact change for the fare. The ride had cost just over three million lira (around seven dollars), but the taxi driver was unable to break the five million lira note I had. He said something to himself in Kurdish before motioning for us to follow him into the hotel where he could get some change.

The Ipek Yolu Hotel was a comfortable two-star hotel with 44 rooms, three elevators and a restaurant/bar -- several steps up from some of our previous accommodations.

"Good morning," a tall man at the front desk greeted us in English.

"Merhaba,"

"Of course," he answered, signaling to another man to take our backpacks upstairs. "Follow him upstairs to the third floor. Hos geldiniz."

While I suspected that any attempt of mine to say hello in Turkish would have been accepted kindly even by Kurds, I felt awkward using it here in Van. I didn't know a word of Kurdish, nor did I know what the local etiquette was. Since the public use of the Kurdish language can be construed as a political statement in itself, would I break any taboos if I learned any Kurdish? For the time being, I would smile and hopefully learn through observation, yet it made me wonder just what it would be like to live in a place where even your choice of language could have profound personal consequences.

After settling into the room and cleaning up from our grueling overnight bus trip, Susanne and I hit the streets of Van to find some breakfast and exchange some travelers cheques. Just off Cumhurriyet Caddesi we found a pleasant pastane

"Kahvalti dahil?,"

"Evet,

As Van's main thoroughfare, Cumhurriyet Caddesi was an energetic artery of Kurdish city life. We veered around oncoming pedestrian traffic of all makes and models: businessmen talking on cellphones, teenage boys hawking snackfood and lottery tickets, old men in skull caps strolling to a local çayhane for some tea. Compared to other cities we had visited in Turkey, we sensed a difference in style here we hadn't seen since Selçuk. Most younger women were casually dressed in jeans or fashionable dresses, while older women wore colorful Kurdish costumes, hiding their faces with intricate lace head scarves. A surprising number of young men wore the knit skull caps that we had only seen on elderly men in other cities. In fact, my initial reaction to one particular man in his twenties was that he was wearing a large Jewish yarmulke rather than an Islamic skull cap. I also noticed a significant number of disabled people in Van, including several beggars whose tattered traditional dress suggested they had come to the big city in the hopes of a better chance. Life has been hard and often violent in rural Kurdistan for a long time; the vibrancy of Van has attracted more than its share of villagers hoping to escape the ravages of poverty and insurrection.

Though Cumhurriyet Caddesi had at least half a dozen major banks along it, none of them seemed willing to exchange money. Several blocks up the road we discovered two exchange offices but neither of them accepted travelers cheques, so we had no choice but to dip into our cash reserves. Susanne exchanged $100 in one office at a rate of 442,000 lira per dollar. We then returned to the Ayça Patisserie, where Susanne ordered a puff pastry and some cookies while I enjoyed my usual Turkish breakfast, along with some coffee and peach juice for both of us. Initially the pastane played Turkish music, but as a young man behind the counter brought over our drinks someone switched the radio station to low-grade American pop. As has been true in so many places we've traveled -- Egypt, India, Thailand, Bolivia -- people seemed eager to supply us with Western music rather than the local variety, whether we liked it or not. At least there were no more swarms of bees trying to steal sips of our peach juice.

After breakfast we passed several tour agencies, each of which advertised bus travel to Iran but not much else. We walked several blocks south of the hotel in search of the Van Tourist Information Center, which was supposedly four or five blocks from where we were staying. I couldn't find any obvious entrance so I assumed it was out of business -- not a surprise considering the indefinite state of emergency here.

Just as we were heading back to our hotel a man stopped us and asked in English, "Where are you going?"

"We're going back to our hotel,", I replied, assuming he worked for the carpet shop on the corner.

"If you need to find the tourist office it's right here," he answered, pointing to a door directly across the street. Somehow I had completely missed it despite the fact it was right in front of our faces. A little embarrassed because of my mistake, I thanked the man before we crossed the street and entered the tourism office.

The Tourist Information Center was a hollow shell of an office, totally barren except for a few posters and a dusty desk counter. Two men were sitting behind the counter, both looking as if no one had visited them in weeks.

I approached the counter, hoping one of them spoke English. "Ingilizce konusuyormusunuz?,"

"Yok,"

Struggling to find out if there were organized minibuses to the local sights I asked in Turkish, "Turist dolmusler var mi?"

Susanne and I approached the front desk to get our room key. "Uç yüz dokuz, lütfen," I said, requesting our key by our room number.

"Good morning," replied the man behind the desk. "Are you interested in tours in Kurdistan?"

"Actually, yes," I answered. "Can you help us arrange a guide?"

"Of course," he said, reaching for a thick folder of tour information. "We can talk in the lounge." Susanne and I followed him towards a couch near the restaurant bar. The man was tall and thin, probably in his late 30s or early 40s, and he had unusually green eyes. His sideburns and bushy mustache showed signs of premature graying.

"Would you like some çay,

"Coffee please," Susanne answered. We could have certainly used the caffeine infusion after the previous night's sleepless bus ride.

"By the way," I added, "my name is Andy, and this is Susanne. What's you're name?"

"My name is Berzan," he replied. It appeared that we had found Berzan Dersimi, the travel agent-turned-hotelier who had been recommended to us.

As our Nescafe arrived a small white cat darted between our sofas. Berzan reached down and picked it up. "This is my new cat," he said. "Have you heard of the Van cat? Its eyes are both green and yellow." Indeed, as the kitten peered up at us it became readily apparent that each eye had a distinct color, as if an eccentric cat lover had purchased contrasting contact lenses for it.

"This is my third Van cat," Berzan continued. "A tourist took my first cat last summer. I was out of Van guiding a tour and someone staying at the hotel took it. The second cat disappeared this spring. They are very valuable outside of Turkey, you know." Susanne and I both tried petting the kitten but its interests must have been elsewhere, for it quickly vanished under the window curtains.

"There is much to see here in eastern Turkey," Berzan explained as he opened a large map on the table. "How much time do you have here?"

"We fly back to Istanbul on Thursday morning," I replied. "That gives us the rest of today, as well as Tuesday and Wednesday."

"You can fit a lot into three days if you get started soon," Berzan said. "Around Van, you could visit Akdamar Island, Hosap Castle, the ruins of Çavustepe and the Rock of Van before the end of the day."

"We have a few priorities," Susanne noted. "We really want to visit the Kurdish palace at Dogubeyazit above everything else, with Akdamar Island second and Hosap castle third. Can we do Dogubeyazit as a day trip or will we have to stay there overnight?"

"Yes, Dogubeyazit can be done in less than a day," he answered. "Two hours each way, it's no problem. And the road from Van to Dogubeyazit doesn't close at night so you can drive back late in the afternoon. You could even visit Ani one day and then visit Dogubeyazit the next day on the way back."

Berzan's last comment caught both of our attentions. The 10th century Armenian capital of Ani was initially high on my list of places to visit in Turkey, but its remoteness along the Turkish-Armenian border far to the northeast made it seem a relatively unlikely place for us to visit before our time was up.

"Is it really possible for us to visit Ani as well?" I asked, both surprised and a little skeptical.

"Yes, it's not difficult," Berzan explained. "If we start now -- within the hour -- we can visit all the ruins around Van today and spend the night here before driving north tomorrow morning. If we leave by 8am we can get to Kars by noon, complete the paperwork for Ani, and visit the ruins in the afternoon. We then spend the night in Kars before driving back to Van the next day, visiting Dogubeyazit and Mount Ararat along the way. With a private car you could do it."

The temptation to include Ani during our three days in Kurdistan was all too enticing. Without a private car, it would take six to eight hours to get to Kars, the city closest to Ani, then another hour to go through the Soviet-style bureaucracy to receive permission to visit the ruins. Ani stands in a no-man's-land between Turkey and Armenia, so potential visitors must jump through all the proper hoops in order to visit it. On top of all this, there is no regularly scheduled transport between Kars and Ani, adding more time and stress to the visit. If we were going to visit Ani at all, we would have to do it with a driver who could take care of all the hassles for us.

"How much would it cost to hire a driver and guide for three days?" I asked, bracing for Berzan's answer.

"Three hundred and sixty dollars," he replied. "That includes driver and all other costs, including hotels and food."

His offer weighed heavily on our minds. If we accepted his offer we'd be blowing a lot more money than we had planned, but Susanne and I both knew this would be the only way we could visit all the major sites of Kurdistan.

"Can we talk it over for a few minutes?" I asked.

"Of course," he replied, lighting a fresh cigarette. "I will be at the reception desk. I could also lower the price some, say to $300, but that is my best offer."

Susanne and I waited a moment until he stepped out of earshot. "We've got to do this," Susanne said, partially to my surprise. "I know it's a lot of money but let's be honest -- do we actually think we'll ever be in this area again?"

"I don't know," I replied, "but I think you're right. At best we might be able to do Akdamar Island and Dogubeyazit on our own. Hosap Castle would be difficult since there's no direct transportation from Van, and Ani would be totally out of the question."

"And I know how much you wanted to go to Ani," Susanne continued. "I think we should do it, as long as we can pay with a credit card and if Berzan will be the one going with us. I really like him."

"Me too," I said. "Let me talk to him and find out." I walked around the corner to the reception desk, where I found Berzan flipping through an appointment calendar.

"If we accepted your offer, could we pay with credit cards?"

"Of course."

"And would you be our driver and guide?"

"Of course."

"Okay.... Let's do it."

"Very good," he said, stamping out his cigarette butt. "We must get started soon. Meet me here in 15 minutes." Susanne and I quickly went upstairs and gathered our cameras and film. It was just before 11am and we had a lot of ground to cover that day.

Susanne and I returned to the front desk several minutes early, where we found Berzan waiting with his car parked outside the hotel. I bought a 1.5 liter bottle of water at the hotel restaurant and met Susanne and Berzan at the car. He drove a Turkish model four-door with a dark green exterior. Out of habit I offered Susanne the front seat, though as she got inside I wondered if we were breaking any taboos by doing this -- normally an unmarried woman would not be allowed to sit next to a man who wasn't closely related to her. But Berzan didn't flinch at our choice of seating arrangements, so I climbed into the rear and manouvered back and forth to figure out which side would have less Anatolian sun pouring in on it. I noticed the seat covers below me were decorated with colorful pictures of Hawaiian beaches, as if Berzan were a chauffeur for surfers and Japanese tourists in his spare time.

Driving south for 10 minutes we soon reached the checkpoint our bus had passed several hours earlier. I noticed that the same plainclothes officer as before was still on duty.

"I will need your passports," Berzan said as he rolled down his window. The official reached inside for our identification and began to speak to Berzan in Turkish. "Paperz Pleez," I imagined a Colonel Klink-like character from Hogan's Heroes demanding of us. Apparently the official recognized our passports for he returned them to Berzan quickly and nodded his head at me. Berzan muttered something to himself in Kurdish as he rolled up his window and turned on the radio. At best these checkpoints must be a daily annoyance to the Kurds. At worst -- well, at worst I could only dare guess.

As we drove beyond the city limits to the rocky countryside east of Lake Van, Berzan reached below his radio and pulled out an unlabeled cassette tape, plugging it into his stereo. An exotic blend of violins and traditional string instruments reached my ears as a muezzin-like

"This is Kurdish music," Berzan said. "I hope you like it."

"Very much," Susanne replied. A pause.

"So are you Kurdish?," I asked, realizing it was a dumb question as soon as it came out of my mouth.

"Yes, I am Kurdish. Most of Van is Kurdish -- 90, 95 percent. The Turkish government says we are but 10 percent of the total population but the truth is much higher -- around 20 percent. There are also many Kurds still in Iraq, in Iran, Syria, even in Armenia..."

"Have you been to Iran?" Susanne asked.

"Yes, to Iranian Kurdistan," Berzan replied. "It is very easy for us to go. We could have lunch there if you want."

"I wish it were that easy for us," I sighed. "It's very difficult for Americans to get visas for Iran. We're allowed to go there, but it's still very difficult. There is still a lot of anger between their government and ours. I really wish we could settle our differences."

As our car drove uphill along the edge of a small dam, Berzan slowed down for a second checkpoint. This time the police were dressed in camouflage and were armed with automatic rifles -- they were jendarma, or paramilitary commandos. Though this was at least our fourth checkpoint since we entered Kurdistan last night, the sight of the jendarma sent an icy chill up my spine. Again I imagined the words "Papers please," but this time the soldier in question wasn't so affable as Colonel Klink. Without thinking I automatically handed Berzan our passports. I then pictured Pavlov ringing his little bell and grimaced to myself. We would be repeating this conditioning experiment a lot over the coming days.

A soldier inspected our passports and Berzan's identification while questioning him on our itinerary. Though he was speaking too quickly for me to understand the entire conversation, I could hear Berzan mention Hosap Kalesi and Çavustepe, our first destinations along the road ahead of us. If we chose to continue past Hosap we would soon find ourselves near Hakkari, the last major town before the Iraqi border. Hakkari has been off-limits for outsiders for many years, and these soldiers clearly intended to send a message that we should proceed no further than Hosap.

Just beyond the checkpoint we began to descend into a valley. Far ahead of us I could see a rocky outcrop jutting from the valley floor, with the ruins of red-brick castle worthy of A Thousand and One Arabian Nights sitting gracefully atop it. We had arrived at the great Kurdish castle, Hosap Kalesi.

In retrospect I believe his retching had actually jarred me back into consciousness -- not a auspicious way to inaugurate our arrival in distant Kurdistan.

In retrospect I believe his retching had actually jarred me back into consciousness -- not a auspicious way to inaugurate our arrival in distant Kurdistan.  castle stood guard over the city. As far as I could tell we probably were not yet in the city of Van since it had a large otogar terminal, not to mention a 100km-wide lake that should have appeared to my immediate left. In fact, I hadn't seen any sign of Lake Van that morning. After groggily staring at my map of southeast Anatolia I surmised we were passing through the town of Bitlis. This meant that we must have been at least two hours away from Van, which would put us at our destination no sooner than 8:30am, a full five hours past our scheduled arrival time.

castle stood guard over the city. As far as I could tell we probably were not yet in the city of Van since it had a large otogar terminal, not to mention a 100km-wide lake that should have appeared to my immediate left. In fact, I hadn't seen any sign of Lake Van that morning. After groggily staring at my map of southeast Anatolia I surmised we were passing through the town of Bitlis. This meant that we must have been at least two hours away from Van, which would put us at our destination no sooner than 8:30am, a full five hours past our scheduled arrival time.  he said to us as he reached our seats.

he said to us as he reached our seats.  Memur Bey,"

Memur Bey," I said as I pulled out our passports from my front pocket.

I said as I pulled out our passports from my front pocket.  pulling into the far side of the terminal's parking lot. Susanne and I exited the bus and quickly walked to the luggage compartment on the other side, eager to confirm that our backpacks hadn't vanished during the many stops throughout the night. To our relief both our backpacks were safe and sound, allowing us to hail a taxi on the other end of the parking lot in order to ride to the city center.

pulling into the far side of the terminal's parking lot. Susanne and I exited the bus and quickly walked to the luggage compartment on the other side, eager to confirm that our backpacks hadn't vanished during the many stops throughout the night. To our relief both our backpacks were safe and sound, allowing us to hail a taxi on the other end of the parking lot in order to ride to the city center.  I replied. "Do you have a double room available?"

I replied. "Do you have a double room available?"

Susanne and I entered the small elevator, fitting rather snugly along with the man carrying our bags. "Merhaba," Susanne said to him, to which he smiled shyly and nodded his head. As always I was eager to carry on the pleasantries -- a polite exchange of "Merhaba, nasilsiniz?" and so on always seemed to be appreciated by Turks when initiated by us. But now we were in Kurdistan, where well over 90% of the population were ethnic Kurds and native speakers of Kurmanji

and so on always seemed to be appreciated by Turks when initiated by us. But now we were in Kurdistan, where well over 90% of the population were ethnic Kurds and native speakers of Kurmanji Kurdish, not Turkish. Turkish, by law, is the public language of exchange in this country, so Kurds can only speak their native tongue discreetly among themselves.

Kurdish, not Turkish. Turkish, by law, is the public language of exchange in this country, so Kurds can only speak their native tongue discreetly among themselves.  shop, the Ayça Patisserie, which appeared to still be serving breakfast.

shop, the Ayça Patisserie, which appeared to still be serving breakfast.  I asked, inquiring about the availability of breakfast to the man behind the counter.

I asked, inquiring about the availability of breakfast to the man behind the counter. kahvalti var,"

kahvalti var," he replied, placing a sheet of fresh baklava behind the glass counter. We were desperately short on cash, though, so we decided to continue up Cumhurriyet Caddesi

he replied, placing a sheet of fresh baklava behind the glass counter. We were desperately short on cash, though, so we decided to continue up Cumhurriyet Caddesi to find a bank and perhaps some other options for breakfast.

to find a bank and perhaps some other options for breakfast.  I inquired.

I inquired. they both replied, raising their eyebrows and clicking their tongues.

they both replied, raising their eyebrows and clicking their tongues.  One of the men pointed to a large map taped to the counter. For reasons beyond my comprehension the map was oriented with east at the top rather than north, so the men and I had a terrible time of referencing points on their map with points on my guidebook's map. After several minutes of frustration I did my best to pretend I had gained some knowledge from our discussion, then thanked them before heading back to the Ipek Yolu Hotel.

One of the men pointed to a large map taped to the counter. For reasons beyond my comprehension the map was oriented with east at the top rather than north, so the men and I had a terrible time of referencing points on their map with points on my guidebook's map. After several minutes of frustration I did my best to pretend I had gained some knowledge from our discussion, then thanked them before heading back to the Ipek Yolu Hotel. perhaps?" he asked. "Apple tea? Coffee?"

perhaps?" he asked. "Apple tea? Coffee?" tenor began to sing.

tenor began to sing.