|

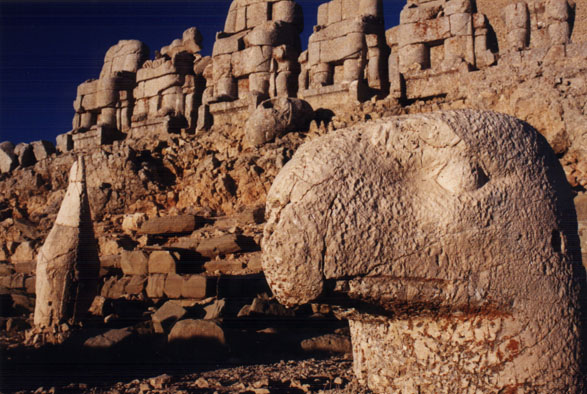

| Giant stone head of Zeus atop the mysterious Nemrut Dagi |

"Andy! Susanne! It's 2:45am... We are leaving in 15 minutes."

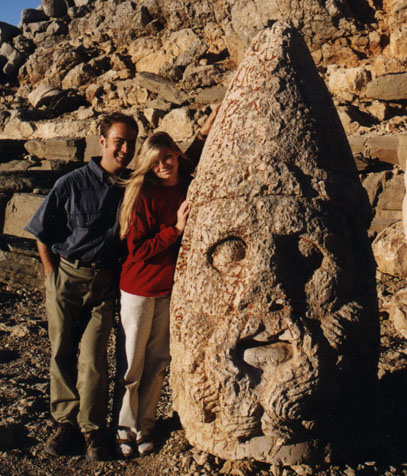

At first I didn't process Özcan's words as he knocked on our door. Rarely have I ever had to wake up so early, but Susanne and I managed to shake away our sleepiness long enough for us to get dressed and join Maggie and Mike for our pre-dawn climb to the top of Nemrut Dagi.

To all of our credit, the entire group met in the lobby precisely at 3am. Özcan, Arkin and the elderly owner of the hotel placed a stack of thick blankets in the van while the rest of us checked our daypacks to make sure we hadn't forgotten anything. We climbed into the bus and began the 90-minute ride to Nemrut's base camp.

Susanne, Özcan and Maggie fell asleep quickly while Mike and I gazed out the windows into the darkness. The first half hour went by quickly as Arkin drove us down a paved road towards Nemrut. We then began the slow 2000m ascent, winding up a crumbling, one-lane gravel road. As we passed a wooden sign marked "Nemrut Mountain Park" in English, Arkin turned on the radio and quietly played a cassette of some of the most hauntingly beautiful music I've ever heard. A blend of vocals, saz and other traditional instruments, the music added another layer to my excitement, which had built up to the point that there was no chance of me sleeping in the van.

Susanne had first introduced me to the idea of visiting Nemrut Dagi nine months earlier when she brought home an enormous coffee table book from the National Geographic library entitled Peoples and Places of the Past. Long out of print, Peoples and Places was a crowning achievement in chronicling the history of human civilization, from the Inca of South America to the Khmer kingdom of Angkor in Cambodia. Of all the wonderful locations and stunning photographs National Geographic could have chosen to put on the cover of this book, they selected an image of gargantuan marble heads propped up on a desolate landscape at sunrise. Based on the design of the heads I had assumed they were of Persian origin, perhaps ruins from Persepolis or Pasargadae. Talking with Susanne later that spring, she insisted the heads were actually from somewhere in Turkey. Eventually we were able to purchase our own personal copies of the book, at which time she proved that the photo had indeed been taken on an obscure, remote mountainside in Turkey. The ancient stone faces of Nemrut Dagi were Anatolia's answer to the giant heads of Easter Island. Susanne and I both agreed that if we ever went to Turkey, we would go out of our way to find this amazing place.

In less than two hours I would finally see these shadowy figures. This was no time to sleep.

Archaeologists have done a fair job piecing together Nemrut Dagi's unlikely history. When Alexander the Great died in 323 BCE, he left behind the largest empire the world had ever been seen, spanning from the Balkans to the Indus Valley. After more than a decade of squabbling, two of Alexander's aging generals began to reclaim much of the Macedonian's empire for themselves. Ptolemy the First consolidated a hellenic kingdom in Egypt while his ally Seleucus I Nicator annexed Anatolia, Syria and ancient Persia, laying the foundation for his new Seleucid Empire. The Seleucids dominated the region for over 100 years, though its power waned as the Romans ascended in the Aegean while the nomadic Parthians reclaimed Persia in 163 BCE. It was in this atmosphere that the strategic, yet obscure Syrian province of Commagene declared its independence from the rest of the Seleucid kingdom in 162 BCE. A mountainous kingdom straddling the frontiers of Parthian Persia and the dwindling Seleucid empire, hellenic Commagene grew wealthy and became an attractive prize to political upstarts and veterans alike.

In 80 BCE a Roman ally named Mithridates I Callinicus successfully positioned himself as the new king of independent Commagene. Like many kings of his time, Mithridates boasted of a glorious ancestral lineage and used it to reinforce his claim to the throne. In his case, Mithridates asserted to be a direct descendant of both Seleucus and the Persian king Darius the Great. By identifying himself with both the legendary Macedonian general and the ancient Persian Achaemenid dynasty, Mithridates advanced his political agenda as the predestined ruler of Commagene.

Mithridates' son, King Antiochus I Epiphanes, displayed an even greater obsession regarding his mythic lineage. Convinced that only a god could be so fortunate to rule a wealthy kingdom and keep cordial relations with both Romans and Persians at the same time, Antiochus saw himself as a god on par with the immortal denizens of Olympus.

The Commagene kingdom lasted another five decades after Antiochus' death in 34 BCE, as it was absorbed into the Roman province of Syria in 17 AD. Over the centuries, long after the Commagene kingdom was forgotten by the rest of the world, a series of earthquakes rocked the giant statues until their heads plummeted to the base of the mausoleum plaza. There they rested in utter obscurity until an Ottoman archeologist stumbled upon them in 1881. In the 1950s, the site became a permanent archeological preservation project. Since then, a steady stream of dedicated travelers has come to pay their respects to the fallen memorial and the eccentric king who built it.

I was somewhat glad that the early morning darkness prevented me from seeing much of the outside scenery, for I could tell that our minibus was swerving along a rocky precipice, with each hairpin turn momentarily revealing what I imagined to be an infinite drop to the valley below. As we neared the top, Özcan woke up and increased the volume of Arkin's haunting music.

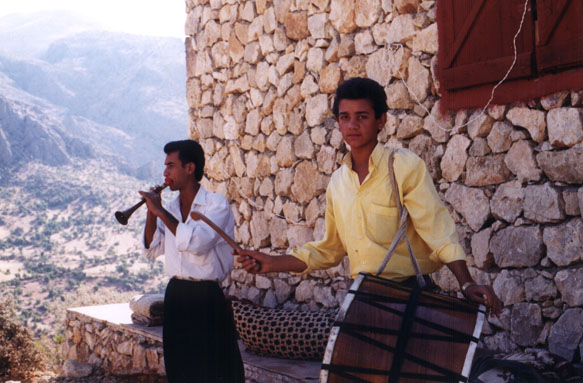

"What are we listening to?" I asked.

"It is Kurdish music," Özcan replied. "Arkin likes to drive to it."

"Is he Kurdish?" I inquired.

"Of course."

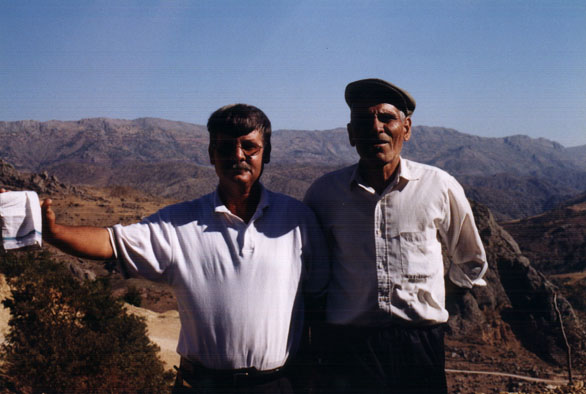

Technically, we had entered the region known as Kurdistan when we passed through the city of Kahramanmaras the previous afternoon. Stretching from eastern Turkey into Iran and down through northern Iraq and Syria, Kurdistan was the realm of the Kurds, a tribal people who speak a family of Indo-European languages distantly related to Persian. Kurds have been in the region since ancient times; in the second century BCE, chroniclers described a group known as the Cyrtii who served as mercenary stone slingers in both the Seleucid and Parthian armies. Two thousand years later, as Ottoman and Persian empires waged war on each other during the 18th and 19th centuries, the Kurdish tribes were caught between the two powers. The Kurds leveraged their skills as warriors with both sides, collaborating with either imperial army whenever it was in their best interest. By the end of World War I, the victorious allies promised the Kurds a nation of their own. the Treaty of Sevres sliced up Anatolia into numerous principalities, with the Kurds receiving the eastern remnants of the Ottoman Empire. But the Turks valiantly resisted the terms of the humiliating treaty and a subsequent Greek invasion, reclaiming the whole of Anatolia under the military leadership of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, hero of the Battle of Gallipoli. Atatürk successfully galvanized the Turkish people and went on to found the republic of Turkey. In the process of forging this modern state, the dream of an independent Kurdistan was shattered, leaving over 20 million Kurds as the largest ethnic group on the planet without their own nation.

It was just after 4am, though, and it was no time to talk politics. I wondered if we would have a chance to chat with Arkin about Kurdish culture, but I imagined we would not come to a time when it would seem appropriate. Our Kurdish education would probably have to wait until we arrived at Lake Van, in the heart of Turkish Kurdistan.

The interior of the concrete structure was far more pleasant. Part teahouse and part opium den, the room was decorated top to bottom in Turkish carpets and giant throw pillows. Several groups of old men sat inside, whispering conversations to each other as they warmed themselves with hot çay. I felt like we were retreating from a fierce winter storm into the cozy confines of a Turkestani yurt. Michael, Maggie, Susanne and I huddled along a wood bench as Özcan ordered us a round of tea and instant Nescafe. Arkin walked over to our table and handed us several guide books about Nemrut Dagi, though most of them were in German or French. Susanne and I thumbed through the books, enjoying the pictures and occasionally attempting to translate the French. On the back of one book I saw a list of other titles available from the same publisher, including one called "101 Humorous Anecdotes by Nasreddin Hodja."

After warming ourselves up, we again wrapped ourselves in blankets and prepared to make the ascent to the summit. Susanne stopped briefly in the bathroom while I played with my camera, attempting to get a long exposure shot of the summit by steadying the camera on a boulder. At 5:15am Özcan gathered us to begin our walk uphill. We stepped over shattered rocks and slippery mounds of gravel, following a steep path that lead to the summit. My blanket was wrapped over my shoulders and around my head -- I imagined I must have looked like Moses ascending Sinai. We walked slowly, stepping 10 or 20 feet before pausing to catch our breath. The cold air stung my lungs as they tried to keep up with my body's need for extra oxygen at this high altitude.

The sky was turning a dark blue by the time we reached a large stone platform near the summit. The platform faced due east, high above the lakes of Atatürk Dam and the surrounding peaks of the Anti-Taurus Mountains. To the west of the platform we found King Antiochus' tumulus burial mound -- a pile of gravel reaching 150 feet into the air. Along the base of the burial mound were the remains of Nemrut's eastern temple, with its famous stone heads propped just below a plaza of decapitated statues.

Being a god, of course, required proper adoration. Just as Ramses the Great had done in Egypt, Antiochus dedicated himself to erecting monuments in honor of his self-styled deity status. Antiochus achieved his own warped form of immortality by commissioning a mausoleum to himself on the summit of Mount Nemrut, (Nemrut Dagi in Turkish), not far from his capital at Arsameia. The tomb itself was a tumulus burial -- an enormous mound of crushed stones that was so high it quite literally raised the summit of the mountain by over 200 feet. Along the perimeter of this tumulus mound, Antiochus installed giant marble statues of himself and his immortal colleagues, including Zeus and Hercules.

Around 4:30am our minibus reached a gravel-cloaked plateau several hundred feet below the summit. Susanne and Maggie awoke from the bone chilling air that rushed into the bus as Özcan and the driver opened their doors. We gathered our blankets, wrapping them over our shoulders as we walked towards what appeared to be a concrete bomb shelter. Just outside the entrance we passed two slumbering backpackers cocooned in high-tech sleeping bags; I couldn't imagine spending the night in such a desolate, frigid place.