|

| Susanne walks along the Ilhara Valley, Cappadokia |

Wednesday, September 1.

Service was slow at the Vegemite Cafe this morning. The owner appeared to have gotten a late start, so when we arrived for breakfast just after 8am he was just sweeping off the sidewalk and warming the ovens. Susanne and I occupied ourselves by playing with the cafe's two resident puppies, who were both more than happy to keep us company. My Turkish breakfast arrived piece by piece -- a slice of bread here, a hard boiled egg there, some honey in between -- while Susanne's pancake appeared even later. Nevertheless the food was good, and the puppies made for fine in-house entertainment.

After finishing breakfast we walked to the otogar, where we found the Hiro Tours minibus waiting for us just outside their offices. Though we arrived 15 minutes before the scheduled 9:30am departure time, Susanne and I were the last in a group of 12 people to board the bus. We were a fairly young group, ranging from college age to early 30s. Our driver, Kadir (pronounced Kadeersh), was a friendly man with a rotund pot belly, fine black hair and a chipped front tooth that gave him a bit of a lisp. He wore a tight Cappadoc@fe cybercafe t-shirt that accentuated his belly, and had a habit of pulling up his baggy blue jeans.

where we found the Hiro Tours minibus waiting for us just outside their offices. Though we arrived 15 minutes before the scheduled 9:30am departure time, Susanne and I were the last in a group of 12 people to board the bus. We were a fairly young group, ranging from college age to early 30s. Our driver, Kadir (pronounced Kadeersh), was a friendly man with a rotund pot belly, fine black hair and a chipped front tooth that gave him a bit of a lisp. He wore a tight Cappadoc@fe cybercafe t-shirt that accentuated his belly, and had a habit of pulling up his baggy blue jeans.

The minibus brought us out of the Göreme Valley towards the neighboring town of Uçhisar, less than ten minutes away. Uçhisar is dominated by a massive tufa formation known as the Uçhisar Kalesi, or Uçhisar Castle. We drove counter-clockwise around the kale,

formation known as the Uçhisar Kalesi, or Uçhisar Castle. We drove counter-clockwise around the kale, parking by a deep gorge on the outskirts of town.

parking by a deep gorge on the outskirts of town.

|

| The city of Uçhisar |

"Behind you is Uçhisar Castle," Kadir explained to us as we stood along the edge of the gorge among rows of grape vines. "The castle, as you may know, is made of tufa, a soft rock made of hardened volcanic ash. Ten to fifteen million years ago, three volcanoes around Cappadokia erupted, leaving thick layers of ash across the valleys. The ash hardened into a rock we call tufa, which is very soft. Over time much of the ash has been worn away, but in certain places the ash has been protected by boulders and debris. The surviving tufa can be seen all over Cappadokia in the form of natural castles like here at Uçhisar, and in the fairy chimneys as well."

"The gorge below is the Pigeon Valley," Kadir continued. "Along the valley you can see what look like little windows carved into the tufa cliffs. These have been carved by villagers for generations. Pigeons are attracted to the holes in the cliffs. They seek protection inside and often lay their eggs there. The people then collect the pigeon droppings, which are very valuable as fuel and fertilizer."

Kadir gave us about 20 minutes to explore the cliffside, taking pictures of Uçhisar Kalesi and the Pigeon Valley below. One of our fellow tour members, a tall German man with sandy hair and glasses, asked Kadir a lot of questions regarding the thickness of the local ash layers and the patterns of past volcanic eruptions. He then picked up small pieces of tufa and told the group that had congregated around him about the natural processes that harden ash into stone.

"Are you a geologist?" Kadir asked.

"No, I am geographer," the German replied, "but I love volcanoes." He continued to point out ash layers in the cliffside, postulating their age and geological circumstance. I made eye contact with a young backpacker with bleached blonde hair and a goatee. He shrugged his head at the geographer and smiled broadly.

|

| Grape vines, Uçhisar |

Susanne, meanwhile, had wandered off to the far end of the cliff, apparently taking pictures of the castle. I took a few minutes to investigate the grapes that seemed to be growing in all directions.

"You can eat them, of course," Kadir said to me. "They should be ripe now."

I pulled a small bunch of bright green grapes off the vine. Though the smaller grapes were a little sour, the larger ones were sweet and juicy.

"Grapes grow very well in Cappadokia," I said to Kadir. "I know there are wineries in Ürgüp. Does Uçhisar have a winery as well?"

"No, not here," Kadir replied. "In Uçhisar and Göreme they grow grapes for other things. White grapes are used in jams, and red grapes are dried into raisins. The people of Cappadokia are still very traditional Muslims, so wine drinking isn't very common. In Ürgüp there are two families who run private wineries. Cappadokia's wines come from their vineyards."

Back on the bus Kadir told us we would next visit one of Cappadokia's famous underground cities. "Usually we take our tour to either Kaymakli or Derinkuyu. Kaymakli is more popular with visitors because you can visit more rooms and go deeper underground. Derinkuyu has less tourists but it is also much smaller: only two underground floors are open. Which would you rather visit?"

Susanne and I had both leaned towards Derinkuyu, since our guidebook had suggested that you were less likely to get caught in a claustrophobic traffic jam of visitors. The rest of the group, though, preferred to visit the site with the more tiers to explore. Neither Susanne nor I felt very strongly about it, so we agreed to visit Kaymakli next.

|

| old Greek houses, Kaymakli |

After driving past several miles of fertile wheat fields we reached the modern town of Kaymakli. The bus dropped us in front of two old houses that had large Greek letters carved just below the roof. "Until the turn of the century, Kaymakli was a Greek town," Kadir explained. "After the First World War, Greece invaded Turkey at Izmir and tried to capture Anatolia. But Atatürk fought back and saved the country. While all of this was happening, many Greeks lived in Turkey and many Turks lived in parts of Greece. The local Greeks fled Cappadokia and the rest of Turkey while Turks in Greece came to Anatolia. Today there are no Greek families in Cappadokia, but some of their houses remain."

We walked past the houses and a row of carpet shops in order to make our way into the underground city of Kaymakli. Kadir led us down a flight of metal steps and brought us into a man-made cave with a tufa doorway leading even further downward.

"This underground city is very old -- over 3500 years old," Kadir explained. The caves were first constructed by the Hatti, an ancient Indo-European people. They built the caves so they could hide when other people invaded their land. Later the Hittites came and expanded the underground cities so they could hold thousands of people. Like today, Cappadokia was a fertile land, and many invaders wanted it for themselves. The Persians came because they also wanted to capture the local horses. Do you know what Cappadokia means? It is Persian for "beautiful horses." Katpatuka, they called this place. The room we are now in is the horse stable. It was difficult to bring horses deep into the caves, and they wanted to keep them near the cave exit if they needed to leave quickly."

Kadir brought us down a passageway into a network of rooms, all lit by rows of lightbulbs. We all had to crouch tightly as we walked down the passages, for there was not enough room to stand up straight. If invaders ever successfully entered the complex, they would have had a difficult time rushing into the heart of the underground city. We paused briefly in a room just off the passageway. Long rectangular holes had been cut into the cave floor.

"This was the local morgue," Kadir said. "As we go deeper into the cave, you will see it gets warmer and warmer. Because of this you had to keep the dead near the top of the underground city, or the bodies would decay very quickly."

|

| Interior of Kaymakli cave room, Cappadokia |

We followed Kadir deeper and deeper into the underground city, visiting kitchens, bedrooms and wine cellars. Between many of the rooms we spotted large wheel-like stones propped near the doorways. "The stone was used as a door," Kadir explained. "From the inside you could roll the stone into place and close the door. From the outside you could not roll the stone back, so it was a good way to block invaders." Perhaps the Flintstones weren't as fictional as we thought.

Six floors down, we reached as deep as we could go into Kaymakli. Kadir pointed out a water well which was used by the city's residents when they wanted to reconnoiter above ground. Spies could sneak in and out of Kaymakli through the wells, which were carefully disguised from above so that invaders would not suspect them as entrances to the hidden city.

In one of the kitchens I noticed large soot stains on the ceiling. "What did they do about the smoke?" I asked Kadir. "It seems dangerous to make fires when you are sealed 100 feet below ground."

"It was okay because of the tufa," Kadir replied. "When you light a fire here, the tufa absorbs the smoke like a filter. It is spread within the rocks, so you can still breath underground. The tufa even prevented the smoke from appearing above ground, so the fires would not give away your location. And with fire you could cook, so you could survive underground for many months. People would not live here all the time, but when they had to, they could be safe here."

The last room we visited before climbing upwards was the town nursery. It was a large, round room, with deep stone pens carved around its edges. "This is where they would take care of the children," Kadir said. "Kids would play here and go to school. When kids were bad they could be put in the stone play pens to keep them away from the others."

I tried leaning into the pen but was not able to reach my hand to the floor. It must have been at least four feet deep -- certainly too deep for any toddler to climb out of. "Tough love, I guess," I joked.

Kadir gave us some time to explore the caves on our own before meeting up top by the bus. I returned to the surface fairly quickly, eager for some fresh air, while Susanne took advantage of the opportunity and wandered underground before meeting me near the entrance. We both wandered around the neighborhood, looking for photo ops while waiting for the rest of the group to reassemble. We each took a picture of an old man separating a bale of hay, just behind the Greek houses we had seen earlier. I tried to take a picture of a group of kids playing, but they weren't very eager to pose for me.

We spent 45 minutes on the bus driving towards our main stop for the day -- the Ilhara Gorge. I really didn't know much about the gorge apart from the fact that it had several Byzantine-era caves and was a beautiful place to go hiking. The bus brought us through the heart of rural Cappadokia, where old women picking cotton with their bare hands would work just a few acres away from high-tech harvesting equipment. Like so much of Turkey, Cappadokia was caught between two worlds -- one traditional and timeless, another at the cutting edge of change.

|

| Ilhara Gorge, Cappadokia |

The minibus pulled off the road not far from Göllü Dagi, one of the three volcanoes that had formed the tufa-dominated topography of Cappadokia. Just to our right the flat earth was ripped open into an 800-foot gorge that gouged the countryside for miles into the distance. Kadir gave us several minutes to take pictures and enjoy the view before starting our descent into the gorge. We drove downward towards the town of Ilhara, winding along a snake-like road. We parked near a restaurant about halfway into the gorge, where we were offered our last bathroom break and a chance to stock up on snacks. Someone bought a large bag of trail mix and generously passed it around, letting each of us take a handful or two.

"We will now walk to the bottom of the gorge," Kadir explained. "It will take about 15 minutes to descend the rest of the way. Before beginning our hike we will visit a small church cave. We will then walk for about an hour, depending on how fast you wish to walk. At the end of the hike we will eat lunch and then drive out of the gorge. Do not worry -- you will not have to climb out."

A sloping path had been cut into the side of the gorge, allowing us an easy descent. I could almost feel the humidity double with every hundred feet downward. Below us I saw a thick forest of trees along the banks of a stream. The stream got louder and louder as we approached. It no longer felt like we were in Cappadokia. Despite being extraordinarily fertile, Cappadokia seemed dry and barren, a distant cousin to the Dakota Badlands. But now were in a lush paradise of greenery and temperate breezes.

Kadir brought us inside a Byzantine-era church at the base of the gorge cliff. Compared to the tufa monasteries of the Göreme Open Air Museum, this particular church wasn't very impressive. The humidity had taken its toll on the church's frescoes, as had generations of bats and other small animals that had called the cave home over the centuries. I was anxious to begin our hike; after breathing the dusty environs of Ephesus and Göreme, a stroll by a stream would certainly be a refreshing experience.

We followed a sandy path from the cave to the stream. Even though we were at the bottom of an 800-foot gorge, a surprising amount of light reached the stream and refracted into fluid patterns of sunbeams along the rocks. A grove of trees extended along both sides of the stream, including what appeared to be several types of fruit trees. As we passed one particular tree, Kadir tore off a small branch covered in pink seedpods.

"Do you know what these are?" Kadir asked. "It's a pistachio tree -- fistik in Turkish."

"Are they ripe enough to eat?" I asked.

"I don't know," he replied. "Try one and find out."

I took a seedpod and bit into it, hoping to expose the pistachio flesh. A bitter syrup squirted into my mouth and on my hands, causing me to spit out the seed. "Definitely not ready," I said. The syrup stuck like glue onto my hands. I tried using water from the stream and a wet wipe to clean my fingers, but they remained as sticky as masking tape.

"We can take as much time as you want here," Kadir said. "You can walk at your own pace and we can meet in about 30 minutes when we reach the spot where there is a large circle of grass and several paths going from it. From there we will have another 20 minutes of walking."

The dozen of us soon separated into several groups, each going at different paces and exploring different spots along the stream. Susanne and I walked along with a young Australian, several Germans and an Indian man with a limp. There wasn't a straight path going along the stream -- we had to climb over and under boulders, jump over minor tributaries and walk on stepping stones in the hopes of not getting our feet drenched. Someone in the group noticed a patch of blackberries just off the stream. I grabbed a small handful and tasted them, hoping that even unripe blackberries would be better than the bitter pistachios that haunted my tastebuds. The larger blackberries, like the grapes in Uçhisar, were absolutely delicious. Several more patches of blackberries dotted the stream bank as we walked, allowing us to pick fresh snacks along the way.

|

Turkish Pronunciation

Interested in learning how to pronounce the Turkish words mentioned in this journal? Check out my Turkish pronunication guide!

|

About a kilometer upstream we met a local family that had been collecting fresh water from the stream. The grandmother led a pair of donkeys while the father and daughter carried water jugs; a mother carried a young boy on one shoulder.

"Merhaba, merhaba," several of us said to them.

several of us said to them.

"Iyi günler," the mother and grandmother replied as they smiled back at us.

the mother and grandmother replied as they smiled back at us.

"Merhaba, nasilsiniz?" I said to the young girl.

I said to the young girl.

"Iyiyim," she replied quietly. "Siz nasilsiniz?"

"Çok iyiyim," I answered. "Ismim Andy. Isminizne?"

"Aysel."

Aysel was a little shy, but she continued to walk by my side for a couple of minutes. Once again I was able to use my meagre repertoire of Turkish to introduce myself and learn more about her.

"Nerelesiniz, Aysel?" I asked.

Aysel?" I asked.

"Belisirma'dan," she replied.

"Amerikaliyim," I continued. "Washington'dun. Yirmisikiz yasindayim. Kaç yasindasiniz?"

"On bes yasindayim."

Aysel's father gave me a big smile, apparently not displeased at our group's intrusion into his family's walk. We soon reached the spot where Kadir had asked us to wait up for the rest of the group, so we bade farewell to Aysel and her family as they headed off to the village.

"Hosça kalin," I said to them.

I said to them.

"Güle güle," the mother and grandmother replied, waving. Aysel waved at us as well but didn't say anything else.

the mother and grandmother replied, waving. Aysel waved at us as well but didn't say anything else.

"That's pretty cool you could carry on a conversation with them," said Franz, the brown-haired Australian.

"Yeah, I've learned just enough to introduce myself, but after about three minutes I run out of things to say," I said.

"So what did you talk about?" Franz asked.

"Well, I said my name was Andy, that I was 28 years old and from the US. She said her name was Aysel, and she was from Belisirma, just upstream from here. She also said she was 15 years old, which seemed older than I expected."

"And you just picked this up while you've been in Turkey?" he continued.

"I got some books on Turkish grammar, then memorized a couple hundred words and some key phrases. But talking with people has really helped me a lot. It's one thing to read about a language, but it's a whole other thing to actually speak it, even if you're terrible at it."

Kadir reappeared along with the rest of our group, so we continued our walk for the last two kilometers. We followed the left bank of the stream as the forest thinned out to a grassy hillside covered in a cascade of boulders that had tumbled from the cliffs above. High up the cliffs you could see dozens of large caves. My mind wandered as I imagined an adventure exploring each cave. Who knows what was hidden high up the cliff side.

Susanne and I walked along the stream, pacing Kadir much of the way. As Susanne and Kadir chatted I noticed an old woman standing inside a large cavern on the other side of the stream. She appeared to be separating wheat from chaff as she beat a carpet of wheat with a broom. Despite our distance from each other we managed to make eye contact.

"Merhaba!" I yelled over to her. "Nasilsiniz?"

"Merhaba," she replied. "Iyiyim."

"Fotograf çekebilirmiyim?" I asked, pointing to my camera.

I asked, pointing to my camera.

"Yok!" she yelled, making a slicing gesture with her right hand. Apparently she had no interest in having her picture taken.

she yelled, making a slicing gesture with her right hand. Apparently she had no interest in having her picture taken.

As we walked further upstream Kadir pointed to a small rock on the ground. Just behind it we could see a black snake taking a nap.

"Look out where you step," he said.

"Do you know if it's poisonous?" Susanne asked.

"I don't think so," Kadir replied. "Let's not wake it up and find out."

We eventually reached our lunchtime stop, an outdoor restaurant adjacent to a small bridge spanning the stream. The group sat down at a long table and ate a selection of chicken and meat dishes. Susanne had some chicken and rice while I ate a plate of köfte kebap. We chatted with the rest of the group, learning about their travels across Turkey and other parts of the world. Franz was spending several months backpacking Europe, while a group of Americans and a Canadian were visiting Turkey after a week in Greece. I talked with Shiv, the Indian man, who was interested in the trip Susanne and I took to India in 1996. As we boarded the bus Susanne spotted another puppy, who welcomed a brief visit from her.

The bus next made a brief stop at Yaprakhisar, a small village known for its fabulous tufa formations in the surrounding hillside. The visit was largely noteworthy because the scenery was used as establishing shots on the planet Tatooine in the first Star Wars movie. As we stood outside and admired the view, a young girl with a severe burn scar across her arm came uphill to visit the group. The Turkish girlfriend of the German geographer struck up a conversation with her. I didn't pay attention to the conversation but the Turkish woman laughed and translated into English, "She said she played the Princess in Star Wars."

We returned to the bus for a brief ride to a far corner of the valley, near the town of Selime. "There are some wonderful tufa caves on the hills above us," Kadir said. "You can explore here for the next hour or so, then meet us back on the bus."

As the rest of the group headed for the hillside I noticed a small Ottoman graveyard on the opposite side of the road. With its beautiful gazebo and unique Turkish gravestones, the cemetery was well worth a quick photograph. I then charged up the stone hillside to find Susanne and the rest of the group, who were now scattered in a network of artificial nooks and crannies reaching hundreds of feet into the air.

|

| Ottoman graveyard near Selime, Cappadokia |

Climbing around wasn't as difficult as it had looked from the ground below. Steps had been carved into the stone paths so it was easier to get a foothold. Long stone tunnels with no obvious destination made exploring even more of an adventure -- you just never knew where you would end up next. Many of the caverns and rooms had at least one side completely exposed to the elements, offering a vertigo-inducing view of the precipitous drop to the valley below. At the next level above me I spotted Chris, the goateed Canadian backpacker, as well as a young Japanese man. By the time I climbed up to the same level, Chris had somehow managed to go up even higher. As fast as any of the rest of us went, he managed to be king of the hill for the afternoon.

Though the man-made caverns of Selime lacked the Byzantine decorations of Göreme, its dazzling geological setting made it a particular highlight for me. Selime was a ancient maze on three axis points, with innumerable places to explore, get lost and find your way out again. I had a difficult time keeping track of Susanne, who appeared to be having a grand time exploring the upper extremes of the complex. Considering that I didn't even know that this place had been on our itinerary for the day, Selime came as a noteworthy surprise.

|

| The graceful rock scenery of Selime, Cappadokia |

By 3pm or so we drove to our next stop, the 13th century Agzi Karahan caravansarai. Though not many others seemed excited about the visit, I was absolutely thrilled. For years I had wanted to travel the great Silk Road caravan route from Turkey to China, and over the last year Susanne and I had even put together a plan for a Silk Road virtual fieldtrip. Though we hadn't been able to get the project funded, we still longed to travel the Silk Road. Until we could work it out, though, we could at least take advantage of being in Turkey to have some preliminary exposure to the great caravan routes of old. The Agzi Karahan caravansarai was our first real taste of the Silk Road, a 700-year-old inn once used by spice traders and gem merchants.

Though not many others seemed excited about the visit, I was absolutely thrilled. For years I had wanted to travel the great Silk Road caravan route from Turkey to China, and over the last year Susanne and I had even put together a plan for a Silk Road virtual fieldtrip. Though we hadn't been able to get the project funded, we still longed to travel the Silk Road. Until we could work it out, though, we could at least take advantage of being in Turkey to have some preliminary exposure to the great caravan routes of old. The Agzi Karahan caravansarai was our first real taste of the Silk Road, a 700-year-old inn once used by spice traders and gem merchants.

We entered the main gate of the caravansarai, which appeared from the outside to be a stout Central Asian fortress. Through the gate we reached a great courtyard, the ruins of a small mosque in its center.

"By the 13th century, the Silk Road was coming to an end," Kadir explained. "But there were still caravans making the trip from Persia and Central Asia to Europe. The Seljuk Turks, who ruled Cappadokia at the time, wanted to guarantee the merchants' safety since they were getting rich taxing the caravans. Every 50 miles, the caravan would reach a caravansarai, a place where they could rest, buy food and even find doctors. Travelers could stay three days at these inns for free as long as they were bringing along trade goods. Keeping the traders happy was good business for the Seljuks."

Turks, who ruled Cappadokia at the time, wanted to guarantee the merchants' safety since they were getting rich taxing the caravans. Every 50 miles, the caravan would reach a caravansarai, a place where they could rest, buy food and even find doctors. Travelers could stay three days at these inns for free as long as they were bringing along trade goods. Keeping the traders happy was good business for the Seljuks."

We wandered around the courtyard, visiting the many rooms scattered around the perimeter. Though the sleeping quarters seemed a little claustrophobic, the animal stables were spectacular -- an imposing vaulted hallway that was more akin to the interior of a cathedral than a livery. On the Silk Road, people were expendable; camels and horses weren't.

As the rest of the group finished exploring the caravanserai, Susanne and I sat across the street at a worn-down cafe -- its chairs rusting away, its table umbrellas fraying at the edges. We drank tea while chatting with Franz about the history of the Silk Road. Undoubtedly he had no idea what he was getting into when he brought up the subject with us, since both Susanne and I had read extensively on the subject.

"So when did the Silk Road start?" Franz asked.

"It goes all the way back to before Roman times. Alexander the Great brought his army along much of this route all the way from Macedonia to Tajikistan and northwestern India. It gave the Mediterranean a real taste for the exotic goods that were found along the way. Later on, there was this Chinese explorer named -- Susanne, what was his name?"

"Chang Ch'ien."

"Right... Chang Ch'ien was sent into the heart of Central Asia by the Chinese emperor Wu-Ti in 138 BCE, but he was captured by Turkic tribes and held captive for over a decade. Eventually he was released and allowed to return to China. Upon his return he told emperor Wu-Ti about the great war horses the Turks used for battle -- the Fergana horses. The emperor was so determined to get some of these horses for himself he sent a series of expeditionary forces into Central Asia. After sieging the city of Fergana, the emperor got his precious horses, but the expedition also introduced the Chinese to the trading opportunities that could be established through Central Asia. So as Greeks and Romans went east to find new trade goods, the Chinese went west, and Central Asia became the conduit for a commercial network that reached from Venice to the Great Wall."

"But the Silk Road wasn't just about selling goods," I continued. "As the caravans plied the trade routes, travelers also passed along ideas -- religion, politics, culture. The Silk Road allowed information to travel thousands of miles between empires that previously weren't in regular contact with each other. In a real sense, the Silk Road was the world's first information superhighway."

"So what caused it to shut down?" Franz asked.

"Times changed," Susanne said. "For hundreds of years, the only way you could get from Europe to China was to follow the caravan routes, which left you at the mercy of bandits, mountains and deserts. It was a dangerous trip. As shipbuilding and navigation improved, it became a lot safer to travel the ocean routes instead of the land routes. The Silk Road eventually dried up, isolating many of the cultures that once thrived because of the caravans."

|

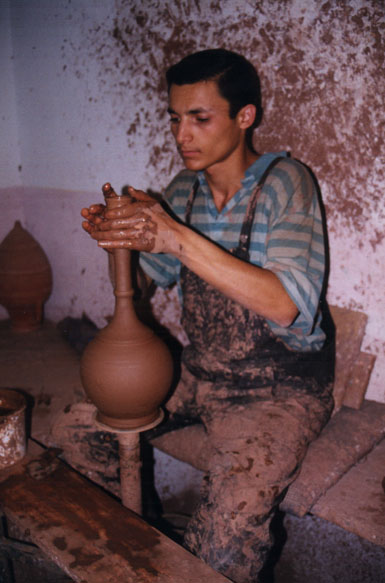

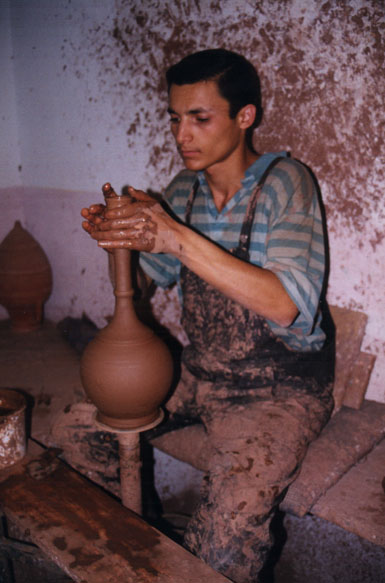

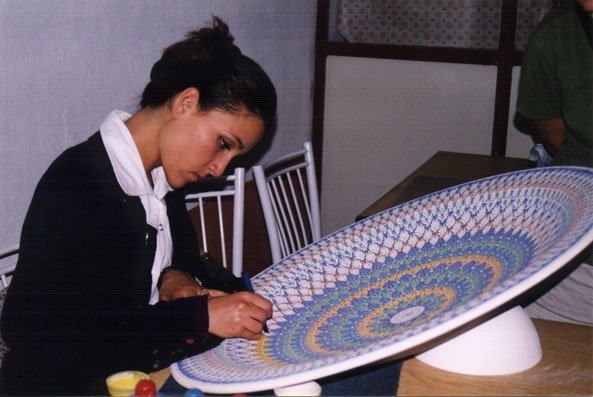

| Avanos pottery maker |

We continued our conversation on the minibus as we drove to Avanos, a small Cappadokian town known for its superb pottery and porcelain. Even though we were about to have a private tour of a pottery making shop, Susanne and I knew that our stop in Avanos was really about sales: a chance for the tour operator to drop a bunch of travelers into a shopping gallery and hope for some cut of the profits. It didn't really bother me as long as the shop wasn't playing the hard sell. Sometimes these mandatory shop visits are nothing more than a chance to browse the local handicrafts. Other times it's a sweaty merchant breathing down your neck, driving you crazy with his constant demands for your business. Hopefully this visit would not be the latter experience.

I had expected the tour to be of a traditional pottery business -- locals have been working the ruddy clay from the local Red River since Hittite times, so I pictured some elderly gent in baggy Turkish trousers spinning a stone pottery wheel by hand. The shop we visited was actually a modern pottery factory, a well-oiled machine in a warehouse tooled for producing tens of thousands of pieces. As we discovered, though, the molding was still done by hand. Kadir introduced us to a young man as he crafted a vase on an electric pottery wheel. A lump of damp red clay spun around at varying speeds as the man used his hands and metal carving tools to shape the damp earth into a piece of art. We also watched another man create a large bowl composed of white clay -- he pressed a handful of clay onto a spinning semi-circle and squeezed it between another semi-circle, not unlike a press or a waffle iron. After opening the contraption and allowing the wheel to spin down to a standstill, he popped out a perfectly formed plate, ready to sit dry before being cooked for three days in an industrial-sized kiln.

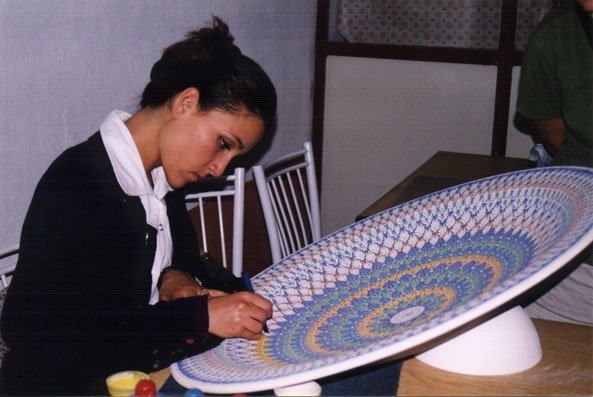

Our last stop along the pottery-making parade route was the design room, where skilled artisans painted intricate, yet delicate patterns onto freshly kilned plates and bowls. I watched one woman paint a complex flower design on a plate that was probably two feet in diameter. For centuries the Turks have been masters of decoration techniques. Islam's prohibition of depicting human forms in art led to a renaissance in abstract Ottoman art, which specialized in symmetrical patterns on pottery ranging from the red and white clay plates of Avanos to the legendary blue Iznik tiles from Western Anatolia.

|

| An artists paints fine details on a plate of Avanos pottery |

Not wanting to interrupt her, I asked one of the tour guides how long it would take to paint the entire pattern.

"It depends on the design and the size of the plate, of course," he said. "As for this plate, she will probably spend three months on it."

Our guide brought us to a table displaying a series of plates at different stages of development. "After the plate has come out of the kiln for the first time, an artist will trace a pattern on it. She will then spend many weeks painting it, following the stencil marks. The plate is allowed to dry completely, then it is coated with a white powder which turns into a clear glaze when cooked in the kiln."

"When it is all done," he concluded, "you end up with a beautiful plate that can sell for many hundreds of dollars." He picked up a fragile white plate that was decorated with a fine design of flowers and grape vines. Handing it to an American woman who was part of the group, the plate suddenly slipped out of his hand and started to plunge to the floor. The woman let out an audible gasp, fearing that she had just caused the destruction of a pricy showpiece. Instead the plate recoiled and then swung in the air on a clear plastic cord secretly wrapped around the tourguide's hand.

"I got you!" the guide exclaimed with glee.

At the conclusion of the tour the guide brought us to a large room lined with traditionally Ottoman seat pillows along the perimeter. We were invited to rest and drink apple tea while a master craftsman demonstrated a traditional pottery wheel, spun with one foot as his hands molded a lump of clay.

"This type of pottery making is very ancient," the tour guide explained. "Pottery wheels like this have been found in Mesopotamia, from thousands of years ago."

The pottery maker spun the clay for five minutes until he produced a small container with a removable lid. "Do any of you know what this is?" the guide asked, pointing to the container. "If you can guess you will get a prize." Our group began to call out a range of items, none of which seemed to hit the mark. I eventually offered my own guess: a sugar bowl.

"Correct!" the guide said. "Please come up and collect your prize."

I walked up to the front of the room and was handed what appeared to be a red clay ashtray with holes in it. "A Cappadokian soap dish," the guide said as he handed it to me.

Our tea still hadn't arrived yet, and the shop guide was running out of ways to keep us occupied. As I started to go and sit down, the guide said, "Why don't we all sing a song? Do you know any good songs?"

The entire group looked at him and me, perplexed. "I don't think that will work," I said, trying to find a way out for all of us. "We're from so many different places we probably don't all know the same song."

(Let's face it -- none of us really wanted to be stuck in this room waiting for tea. Kadir had probably gone off for a smoke break and had left us in the shop guide's care.)

"Okay, so how about if we have a volunteer to make some pottery?" he responded, not sure what to do next. The Turkish-German woman offered to give the pottery wheel a whirl, but ended up making what appeared to be a melted plastic mug that had been nuked for too long in a microwave. Our teas finally arrived, and most of us drank them quickly just so we could get out of this awkward situation. The guide told us that we had about 20 minutes to wander the galleries and look at their pottery -- and if we bought now, we'd receive a ten percent discount.

The group wandered the showrooms aimlessly, killing time until Kadir could get us out of there. There were beautiful museum-quality pieces that were available for purchase, but the salespeople didn't seem to grasp that they were dealing mostly with a cash-strapped backpacker crowd. Eventually, Kadir appeared from his cigarette break and said we could return to the bus. Most of us headed outside quickly, eager to move on to our last stop. While we waited for a few stragglers to join us, Susanne and I played with a litter of four hyperactive puppies that resided next to a small guard post.

"I just don't get it," Susanne said as the small dogs climbed all over us. "There are more puppies per square mile in Turkey than any other country we've visited."

The sun was going to set in just over an hour so we drove onward to our final stop, the Valley of the Fairy Chimneys near the village of Zelve. The minibus deposited us inside an asphalt parking lot lined with a row of souvenir stalls. Kadir said we would have 45 minutes to explore the valley before regrouping atop a hill in order to watch the sunset. Our group scattered in several directions, wandering off to marvel at Zelve's famous fairy chimneys, one of the most photographed collections of classical tufa formations in Cappadokia. While other fairy chimneys often varied in shape and size, Zelve's chimneys were all equally enormous, equally beautiful, and -- well, let's be honest -- equally phallic. Embarrassingly phallic, in fact. It was hard not to giggle when looking upwards at these rosy-hued pillars, but after a few minutes the bawdy novelty wore off and the fairy chimneys returned to being just impressive natural rock formations.

|

| The fairy chimneys of the Rose Valley, Cappadokia |

Susanne headed off down a path towards a boy who was offering camel rides while I took a detour through several acres of grape vines. Hundreds of bushels of grapes had been picked that week and were now drying into raisins on dozens of plastic tarps. The grapes were shriveling yet still juicy, giving off a distinct fermentation smell that reminded me of past visits to Sonoma Valley vineyards. One or two acres of grapes had yet to be picked. I discreetly reached down and pulled of a few for myself, plopping the plump red fruit into my mouth one at a time.

|

| A camel lounges around the Rose Valley, Cappadokia |

I met Susanne over by the camel and followed her up a stony embankment that led to several ancient tufa churches tucked neatly in the back of the valley. The churches were only reachable by a pair of rickety wooden ladders. We both climbed up carefully and visited the interior of the main church. There was little to see up there except the view, since the interior of the cave had faded away long ago.

I was eager to climb down the ladder to get both feet back on the ground, but halfway down my descent Susanne observed, "The light is really good at the top. Go back so I can take a picture." Holding on for dear life I climbed back up, then allowed the Turkish-German couple to head back down the ladder. Susanne snapped the picture and then encouraged a Japanese man to go up so she could take a picture of him with his camera.

Again passing the boy with the camel, Susanne and I crossed the valley and climbed the hill for sunset. The hill was a hemispherical mound of tufa about 100 feet high. Though it wasn't very steep, the fact that the hill was constantly crumbling fine bits of tufa made every step slippery and potentially dangerous. I settled myself atop the hill while Susanne continued onward, walking up and down a thin pass that connected several other hills. While I fiddled with my zoom lens and some of Susanne's optical filters I shared a bottle of Cappadokian wine with an American couple who had brought along a small picnic for sunset.

Susanne returned to my spot on the hill just after sunset, giving us enough time to pack up our cameras before returning to the minibus. Kadir appeared and told us it was time to go, leaving me and the two other Americans with a full glass of wine to bring back to the bus. We offered a glass to Kadir. "No thank you," he said. "I am not very religious but I still do not drink."

The bus dropped us off back in Göreme in front of the otogar. Several members of our group were going to eat at the Orient for dinner. Having dined there just the night before, Susanne and I declined and opted for the Sultan Restaurant across the street. We both ordered Turkish pizzas while I had a cool glass of Efes Pilsner. A trio of chainsmoking Japanese women sat next to us, along with a suave young Turkish man. I had assumed they all knew each other but just as their food arrived I heard one of the women ask him, "So what is your name?" Neither Susanne nor I could figure out why they were dining with him. Later we struck up a conversation with them and discovered that one of the women had learned her English in New York, giving her a humorously thick Long Island accent.

Several members of our group were going to eat at the Orient for dinner. Having dined there just the night before, Susanne and I declined and opted for the Sultan Restaurant across the street. We both ordered Turkish pizzas while I had a cool glass of Efes Pilsner. A trio of chainsmoking Japanese women sat next to us, along with a suave young Turkish man. I had assumed they all knew each other but just as their food arrived I heard one of the women ask him, "So what is your name?" Neither Susanne nor I could figure out why they were dining with him. Later we struck up a conversation with them and discovered that one of the women had learned her English in New York, giving her a humorously thick Long Island accent.

Back at the Ufuk hotel I had hoped to get some journal writing done. Susanne and I were both pretty beat from the long day, and we both fell asleep soon after settling in for the night.

where we found the Hiro Tours minibus waiting for us just outside their offices. Though we arrived 15 minutes before the scheduled 9:30am departure time, Susanne and I were the last in a group of 12 people to board the bus. We were a fairly young group, ranging from college age to early 30s. Our driver, Kadir (pronounced Kadeersh), was a friendly man with a rotund pot belly, fine black hair and a chipped front tooth that gave him a bit of a lisp. He wore a tight Cappadoc@fe cybercafe t-shirt that accentuated his belly, and had a habit of pulling up his baggy blue jeans.

where we found the Hiro Tours minibus waiting for us just outside their offices. Though we arrived 15 minutes before the scheduled 9:30am departure time, Susanne and I were the last in a group of 12 people to board the bus. We were a fairly young group, ranging from college age to early 30s. Our driver, Kadir (pronounced Kadeersh), was a friendly man with a rotund pot belly, fine black hair and a chipped front tooth that gave him a bit of a lisp. He wore a tight Cappadoc@fe cybercafe t-shirt that accentuated his belly, and had a habit of pulling up his baggy blue jeans.  formation known as the Uçhisar Kalesi, or Uçhisar Castle. We drove counter-clockwise around the kale,

formation known as the Uçhisar Kalesi, or Uçhisar Castle. We drove counter-clockwise around the kale, parking by a deep gorge on the outskirts of town.

parking by a deep gorge on the outskirts of town.