|

| Boy with bicycle, Wat Aham, Luang Prabang |

Friday, November 14

A Bicycle Tour;

Dinner Fit for a Princess

Today was Wat Day in Luang Prabang - not that anyone had declared it as such, of course. As I mentioned earlier, Susanne had worried at Angkor that she wouldn't see enough monks. Luang Prabang, with its 32 monasteries, I assured her, would essentially be One Big Monk. And today was the day we would go out in search of that Monk.

in Luang Prabang - not that anyone had declared it as such, of course. As I mentioned earlier, Susanne had worried at Angkor that she wouldn't see enough monks. Luang Prabang, with its 32 monasteries, I assured her, would essentially be One Big Monk. And today was the day we would go out in search of that Monk.

Breakfast at the hotel wasn't very satisfying - the sliced baguettes were so stale they scratched the roof of my mouth. At 8:30am a heavy fog hung over Luang Prabang, with only the river valley visible in full. Until the sun situation improved, picture taking would be a questionable task. I suggested we visit the royal palace, which was open precisely from 8:30am to 10:30am each day - two hours the Lao government would allow its people a peak into its glorious, yet all-too-recent monarchical past.

|

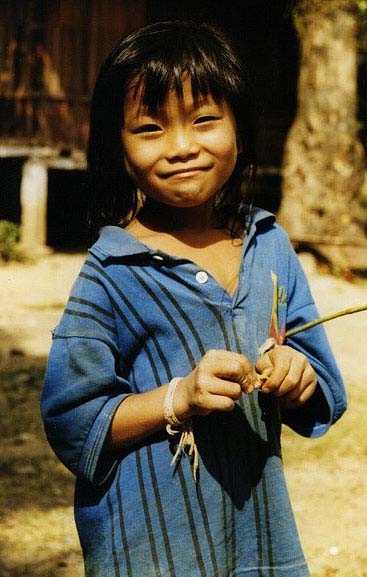

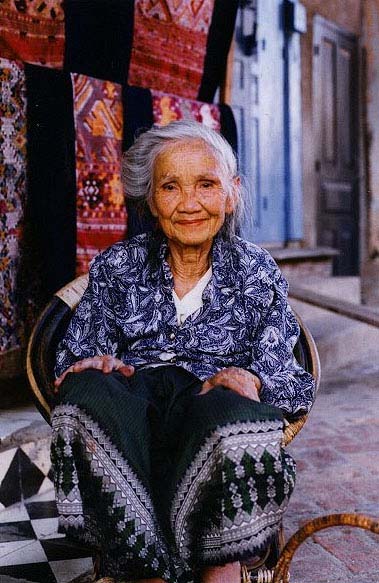

| Hmong woman, Luang Prabang |

I received a permission slip from the hotel for 1000 kip; without it, we wouldn't be allowed into the palace. We then walked down the street to the palace, past a row of Hmong women selling patches of woven fabric. From the side the palace looked like a flat, one-story college campus building. But as we crossed to the front of the palace, it began to show off the regal splendour that I had expected. A wat-like spire reached upward from its center as marbled steps led way to the entrance, where we were requested payment of another 1000 kip each, the stowage of our bags and cameras, and the removal our shoes.

Before actually going through the front door of the palace, we were ushered off to the far right side, where we could see a collection of royal Buddha images through an iron gate. Among these relics sat the Pha Bang, the 83 centimeter solid gold Buddha that gives Luang Prabang its name: the City of the Great Pha Bang. According to legend, the Pha Bang is almost 2000 years old, having made its way over the centuries from its birthplace in Sri Lanka to Laos, where it was given to Fa Ngum, the Lao warrior who used his connections in the Khmer empire to wrestle northern Laos from the Thai kingdom of La Na (Lanna). With the Pha Bang is his possession, Fa Ngum declared himself the first king of Lane Xang Hom Khao, A Million Elephants and a White Parasol. Along with the famed Emerald Buddha, the Pha Bang served as the legitimator of Lao sovereignty. Over the years, though, the Thai empire managed to capture both the Emerald Buddha and the Pha Bang. Though Siam kept the Emerald Buddha for themselves, King Rama IV returned the Pha Bang to Luang Prabang in the 1860s, where it has remained ever since.

Or has it? Many Lao believe that the Pha Bang on display is actually a gold plated replica, while the original statue is kept in Vientiane or (even worse) Moscow. Lao officials deny this, of course. The Great Pha Bang was truly a marvelous statue, but in all honesty, if I hadn't known the history behind it, I might have easily overlooked it. The Pha Bang's unusual display on the outside right of the museum and its lack of fanfare was a far cry from the near-idolatrous homage paid to the Emerald Buddha in Bangkok, or even the simple dignity of the Gold and Emerald Buddhas in Phnom Penh's Silver Pagoda. This Buddha inspired no holy awe. I wondered if that's exactly what the current communist government intended.

Susanne and I entered the royal audience chamber, with its splendid tile murals and grand throne. The other rooms of the house, equally regal in their arrangement, were more scaled back, at times seeming utilitarian. The King's and Queen's bedrooms appeared as they were left in 1975 - empty rooms apart from basic sets of teak beds, chairs, and tables. A small dining room was decorated in a 1950s art deco style - more tasteful than Graceland, but a distance Asian cousin nonetheless. The final rooms displayed gifts from other nations to the Lao PDR, including a moon rock given by President Nixon. According to the Lonely Planet guide, gifts were labeled as being either from socialist or capitalist nations, but since all of these labels were in Lao I couldn't tell the difference.

We stepped outside and put our shoes on. The sky was opening up, the fog beginning to clear. Susanne and I were both a bit hungry due to our poor breakfast, so we walked to a bakery on Luang Prabang's main road. It was crowded with farangs eating muesli and baguettes, so we got comfortable and enjoyed an order of banana bread and coffee. We talked about renting motor scooters that day, but next door the asking price was $20 a bike, much more than we wanted to spend. On the other side of the bakery a bicycle shop rented bikes at 2000 kip a day - about $1.20. We rented two of them and went on our merry way.

We didn't have a particular itinerary for our bicycle tour so we started by heading up to the tip of the peninsula and then to the left along the quiet boulevard along the Mekong. There was a slight decline in the road so we coasted along as other bicyclists and the occasional motor scooter rider passed us in the other direction. The road curved away from the Mekong eventually, so our view was no longer as pleasant. Upon reaching the perimeter of town we cut left, past the town's lone Shell station and the Malee Lao Food restaurant where we had eaten the night before.

There wasn't much of interest in this part of town, so we took another left and soon reached the quaint wooden bridge over the Nam Khan that we had crossed yesterday. Because it was a single lane bridge, we waited for a stoplight to signal our turn to cross the river. I looked to the right as we rode over the bridge and saw a wat perched over a hill beyond the river. We parked our bikes on the far side of the bridge and doubled back by foot to get a better view. If it weren't for the wat I could have pictured this bridge, stream and valley scene to be at home in New Hampshire rather than Lao PDR.

We returned to our bikes after pausing to say hello to some more children who were on their way to school. Then we headed back down the dirt path, over the main road and onward down another semi-paved road where more wats awaited us. After 200 yards or so we reached a fork in the road by a small wat. Our Lonely Planet map didn't show a fork at this particular point, so we took a guess and went right. Numerous schoolchildren passed us on foot, yelling "Hello!" in English. There was a very small wat at the end of the street, but we figured we had gone in the wrong direction, so we turned around and continued past the earlier fork in the road.

There was a residential neighborhood with houses ranging from small shacks to shiny teak cottages with fresh flowers on every window sill. Scores of butterflies hovered over rows of rose bushes. So many butterflies in this country, I thought; I had never seen anything like this before. Land of one million elephants? Land of one million butterflies seemed much more appropriate.

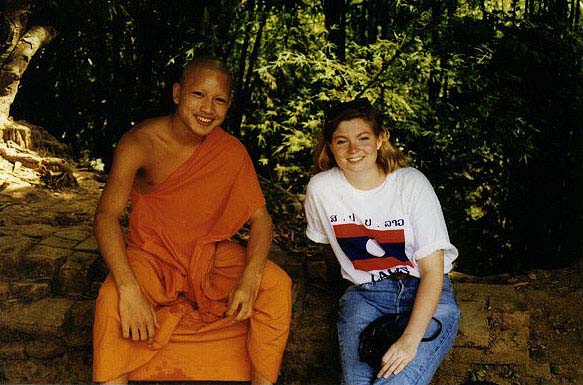

Just beyond another wooden bridge we found Wat Sa-At, a minor monastery with a beautiful view of Luang Prabang and the Nam Khan river. Three old monks sat in a wooden hut, apparently in the midst of a reading, but they paused to smile at us and say hello. I sat for a while on a bench near the river, contemplating the serenity of the scene before me. It was now around 12:30pm and the heat of the mid day would soon be upon us, so we decided to return to the center of town. But a young novice approached us and said hello, then asked if we spoke any Lao. Naively, I responded with "Phom phoot phasaah Thai nitnoi, khap" - "I know a little Thai." The young novice grinned and called out something in Lao to a friend, but I knew exactly he was saying: "Hey, come over here! This farang says he speaks Thai!" His friend, another novice, approached us and said to me, "Sawatdee khap, khun phoot phasaah Thai, chai mai khap?" I timidly responded, "Phoot Phasaah nitnoi, mai mahk, khap" - "I speak a little, not very well, though." We then began a difficult dialogue (difficult for both of us, I imagine):

says he speaks Thai!" His friend, another novice, approached us and said to me, "Sawatdee khap, khun phoot phasaah Thai, chai mai khap?" I timidly responded, "Phoot Phasaah nitnoi, mai mahk, khap" - "I speak a little, not very well, though." We then began a difficult dialogue (difficult for both of us, I imagine):

"Khun cheu arai khap?"

"Phom cheu Andy, khap."

"Khun Andy, khun maa chaak tee nai khap?"

"Maa chaak Washington DC, khap. Pen khon American."

"Khun chohp PahtLao, chai mai?"

"Huh?"

"PahtLao. Khun.. Chohp... PahtLao... chai mai?"

I was stumped by this one, and responding "huh?" again and again probably didn't give him the answer he wanted. The novice repeated it one more time, smiling patiently and gesturing to the air around him with his hand. "Oh!" I exclaimed. "Do I like Laos?" Woops, I should have expected that question. "Chohp khap! Phom chohp Pathet Lao mahk mahk!" Both he and the other novice understood my response and grinned, nodding their heads approvingly. With each new question, though, my comprehension got worse. I knew he was asking me how long we had been in Laos, when we planned to leave and the like, but I didn't know how to say the answers in Thai, apart from throwing out a few numbers. So I started to spew out a laundry list of simple Thai sentences, just enough to cover any potential questions he might still want to ask. He smiled as I talked, nodding in comprehension with each comment. Eventually we said goodbye ("Shohk dee!"), as I gave a quiet sigh of relief that I had survived my first real dialogue in Thai - a chat with a nice young Lao who didn't speak a word of English. I just wondered if I'd ever get a similar opportunity in Thailand. Perhaps I should have studied Lao instead.

|

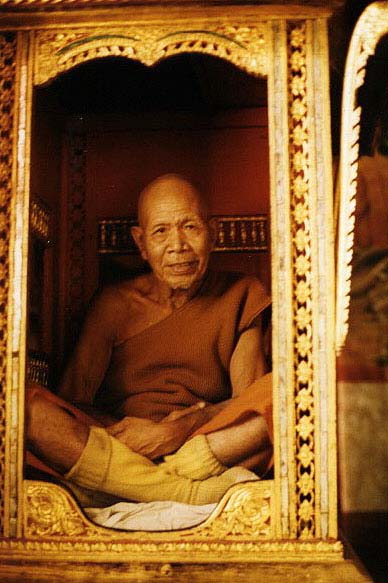

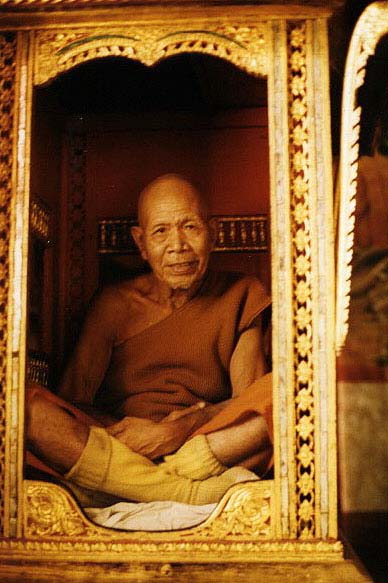

| A Monk in his prayer chamber, Wat Aham |

Susanne and I returned to our bikes and crossed back over the wooden bridge to the Luang Prabang peninsula. We caught some shade at another minor wat and then continued right to Wat Wisunalat, locally known as Thaat Makmo - the Watermelon Stupa. Originally constructed in the early 1500s, Thaat Makmo was one of the oldest wats in Luang Prabang. Though its sim is nothing unusual, Wisunalat is best known for the large stupa in front of it, a hemispherical structure built in 1513 that looks like a half of a watermelon jutting out of a white stone base. Just next to the stupa was Wat Aham, a quiet monastery best known for two large Bodhi trees and its former role as the residence of the Sangkhalat, the Supreme Patriarch of Lao Buddhism. Outside of the sim an old monk showed us around and into the sim, where he offered to sell us "wats in a bottle" - glass bottles with wooden sims inside, not unlike a ship in a bottle. He then sat in a small gilded booth, barely bigger than he was, and invited us to take pictures. We smiled, took some shots and thanked him, eventually leaving the sim as he remained quite comfortably inside his booth. As we crossed through the compound, a group of boys played with a bicycle. They laughed and mugged for pictures enthusiastically.

Originally constructed in the early 1500s, Thaat Makmo was one of the oldest wats in Luang Prabang. Though its sim is nothing unusual, Wisunalat is best known for the large stupa in front of it, a hemispherical structure built in 1513 that looks like a half of a watermelon jutting out of a white stone base. Just next to the stupa was Wat Aham, a quiet monastery best known for two large Bodhi trees and its former role as the residence of the Sangkhalat, the Supreme Patriarch of Lao Buddhism. Outside of the sim an old monk showed us around and into the sim, where he offered to sell us "wats in a bottle" - glass bottles with wooden sims inside, not unlike a ship in a bottle. He then sat in a small gilded booth, barely bigger than he was, and invited us to take pictures. We smiled, took some shots and thanked him, eventually leaving the sim as he remained quite comfortably inside his booth. As we crossed through the compound, a group of boys played with a bicycle. They laughed and mugged for pictures enthusiastically.

Back at our own bikes, I looked up the road and saw a splendid view of Phu Si, the 100 meter hill that sits at the center of the Luang Prabang peninsula. At its summit I could see Thaat Chomsi, the 80 foot stupa that dates back to the early 1800s. I had a momentary flashback to the stupa of Swayumbunath near Kathmandu, its mystical eyes peering out in four directions from its hilltop perch. There were no eyes looking down at me from the top of Phu Si, but yet I felt the same serenity here that I had last felt in the Kathmandu Valley. Luang Prabang was truly a special place.

Back at our own bikes, I looked up the road and saw a splendid view of Phu Si, the 100 meter hill that sits at the center of the Luang Prabang peninsula. At its summit I could see Thaat Chomsi, the 80 foot stupa that dates back to the early 1800s. I had a momentary flashback to the stupa of Swayumbunath near Kathmandu, its mystical eyes peering out in four directions from its hilltop perch. There were no eyes looking down at me from the top of Phu Si, but yet I felt the same serenity here that I had last felt in the Kathmandu Valley. Luang Prabang was truly a special place.

We dropped off the bicycles at the shop around 1pm and grabbed some more banana bread at the bakery. There were two Americans inside - a man from New York and a woman who happened to be from DC - as well as a tall, mysterious Englishwoman. The man was on a round-the-world meditative trek, while the American woman had taken six months off from the World Bank to travel across Asia. I'm not exactly sure what the Brit's itinerary was, though she did talk about how she thought bald men were very attractive. Susanne and I finished our snack, so we retreated to our air-conditioned room at the Hotel Phousi for a couple of hours - we were sweaty and in dire need of showers at this point.

|

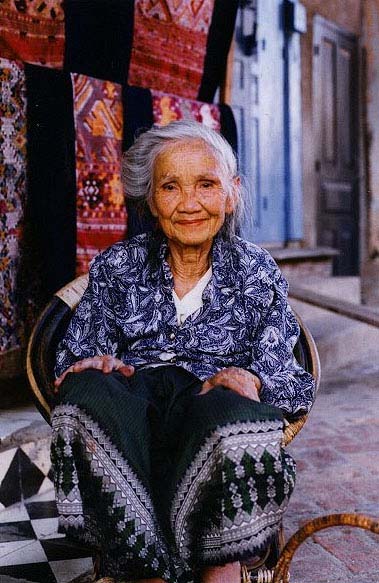

| Lao cloth seller, Luang Prabang |

By mid afternoon we decided to visit the two wats just behind the hotel, Wat Ho Siang and Wat That. A group of novices horsed around near Wat That's drum house, tossing a ball at each other and occasionally banging on some large cymbals. Susanne was looking a bit tuckered out - she had been suffering from insomnia for a few nights - so we decided to take it easy for the rest of the afternoon and focus our efforts on souvenir hunting. Most of the shops carried similar items - carved teak, cymbals and gongs, opium scales, and above all, a wide selection of beautifully embroidered textiles, a specialty of many of the local hilltribes. The workmanship was both complex and delicate, yet most pieces sold for less than 10,000 kip - about seven dollars. Susanne wanted to buy some cloth even though we couldn't figured out what to do with linen shaped in a 2"x7" rectangle. Hang it, I guess. At one shop run by a severely hunched over old woman, Susanne found a gorgeous red woven cloth for 6000 kip - four dollars. The old woman even appeared ready to settle for 5000 kip until her husband arrived, at which point she steadfastly stuck to 6000 kip. Either way it was a great bargain, so Susanne bought the cloth.

Down the road we could hear drumming from Wat Mai, one of the largest wats in town. Novice monks were hammering out a fast rhythm in the drum house, using the main drum, two gongs and some large cymbals. Some tourists crowded around the drum house trying to get pictures, and the monks managed to ignore them. We eventually joined in the intrusion and got some nice pictures up close. We then headed further down the street in search of my own souvenirs. I settled on a piece of carved varnished teak - a profile of a menacing Lao demon.

Down the road we could hear drumming from Wat Mai, one of the largest wats in town. Novice monks were hammering out a fast rhythm in the drum house, using the main drum, two gongs and some large cymbals. Some tourists crowded around the drum house trying to get pictures, and the monks managed to ignore them. We eventually joined in the intrusion and got some nice pictures up close. We then headed further down the street in search of my own souvenirs. I settled on a piece of carved varnished teak - a profile of a menacing Lao demon.

At 5pm we opted for an early dinner at the Villa Santi, commonly known as the Villa de la Princesse. This 120-year-old colonial mansion was the home of Crown Princess Khampa, the highest ranking member of the Lao royal family to survive the Pathet Lao takeover in 1975. The villa was confiscated in 1976 but returned to the princess in the early 1990s. She has since renovated the place into a luxury inn and Lao-French restaurant, whose chef is the daughter of the last King's private chef. The inside of the villa glistened with varnished teak, but we opted to sit on the balcony overlooking the town.

Susanne and I decided to splurge that night, ordering our meal course by course. We started with bowls of soup - a buttery vegetable soup called Soupe de la Princesse, which was too oily for my taste, and a marvelous onion and wild mushroom soup. The mushrooms, I realized, were those delicate pasta-like fans I had enjoyed the night before in my soup at Malee's restaurant. Next, we ordered a plate of seven small spring rolls, each packed with cellophane noodles and ground meat. The soup and spring rolls could have been a meal in itself but we continued with entrees of a lemongrass stuffed chicken baked in banana leaves - white meat, finally! - and traditional Lao sausage which tasted not unlike a hearty German sausage, though I dared not ponder its ingredients. Steaming hot rice complimented the entrees - the waiter would scoop fresh heaps of the stuff each time we came close to cleaning the plate. Feeling as if we would burst, we arrogantly pushed forth, ordering a dessert of fresh pineapple and papaya and the best creme caramel I've ever had. Fully engorged, we slumped over in satisfaction, smiling in earnest. It was the most expensive meal of our trip - a little over 20,000 kip total, around 12 dollars. We promised ourselves we'd be back tomorrow.

We enjoyed a slow walk back to the hotel, passing the many wats and streetside shops we had come to know so well. Out in front of the old woman's shop where Susanne had purchased her cloth, her two grandchildren played with one of the neighbor's children. We had seen these two kids before - a two-year-old boy and a three-year-old girl - in our previous walks, and even managed to get some pictures of them. This time, though, upon seeing us they charged along side, putting their hands together in a prayer-like wai and said "Sabai dee!" in a quick and cute way that only a small child could. I greeted them back and they repeated the gesture. "Sabai dee!" they yelled. This went back and forth as the boy explored my camera and even gave me a small vanilla cookie, about the size of a dime.

I then jokingly held out my hand, palm up, and said "Gimme five," to which Susanne responded by slapping her hand onto mine. I did the same to her and we repeated the process as the two kids gazed in wondrous fascination. I then put out my hand to the boy and said "gimme five" to him. He stared back blankly for a second, but his sister, apparently a quick study, slapped down her hand into mine. Getting her to turn her hand over in reciprocation took some coaxing but she soon got the hang of it. Eventually the little boy caught on and slapped my hand while letting out a joyful "Gaa!" noise. The kids now had their first taste of inane American culture. Within a few minutes, the little girl had graduated to doing both hands at once, while the boy did his best to keep up. Their mother and grandmother sat by and laughed as we played together, but I could see it was getting well past their bedtime - ours too, for that matter. So we waved bye-bye to them, and the little boy gave us a valedictory "Sabai dee" as we parted.

Not far from the hotel, three monks walked past us from behind. They all said "sabai dee" and "excuse me," but one of them, a tall, headshaven young man with a huge orange knit cap sitting on the top of his head, said "Excuse me for yesterday" as he walked on by. At first I attributed his comment to developing English skills but I then wondered if he could be the novice who had invited us to the concert. There was no way I would have recognized him in the orange cap and freshly shaven head. I hoped he had simply misspoken.

Another group of novices caught up with us from behind. One of them, a lanky fellow with a confident smile and an easygoing gait, strode right next to us and said, "So where are you going?" which is a common form of hello in Thai and Lao (not unlike "How's it going?"). "Hotel Phousi," I said. "Long day." "We're going to a concert. All the local monks will be there," he replied proudly, as if he were in charge of community events himself. We chatted with him and eventually asked if we could go to the concert, but he pointedly said "No." He paused for a moment and then continued, "Village people only. Special religious festival." It was a Buddhist full moon event and it probably would have been inappropriate for nonbelievers to stroll in with cameras in hand. That's OK. We talked about his shaved head for a while. "Shaved today, for the full moon," he said. Apparently the novices would shave their heads again for each full moon. The tall novice had a street-wise air to him that I hadn't noticed in any of the other young Lao men we had met. Clearly this kid was the leader of the pack. We parted company across the road, just by the hotel gate. "Good luck," he said to us, smiling. "Shohk dee," I replied, translating it back into Lao. "Shohk dee!" he laughed. "Very good, very good..." He waved goodbye and walked down the road, his band of younger novices trailing by several footsteps.

Susanne and I returned to the hotel and got ready for bed. As I shut off the lights, I thought of the little boy and his sister shouting "Sabai dee" to us. I went to sleep with a smile on my face.

in Luang Prabang - not that anyone had declared it as such, of course. As I mentioned earlier, Susanne had worried at Angkor that she wouldn't see enough monks. Luang Prabang, with its 32 monasteries, I assured her, would essentially be One Big Monk. And today was the day we would go out in search of that Monk.

in Luang Prabang - not that anyone had declared it as such, of course. As I mentioned earlier, Susanne had worried at Angkor that she wouldn't see enough monks. Luang Prabang, with its 32 monasteries, I assured her, would essentially be One Big Monk. And today was the day we would go out in search of that Monk.