|

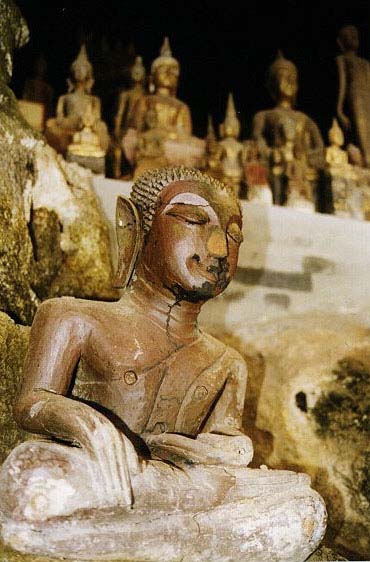

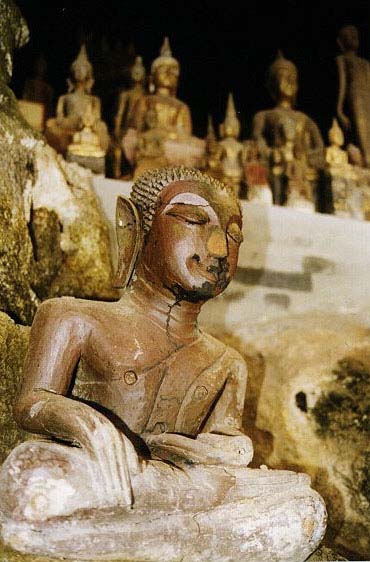

| Buddha statues, Pak Ou Caves |

Saturday, November 15

The Pak Ou Caves; Finding our Missing Monk Friend

Susanne and I had a 9am rendezvous this morning with the middle aged boatman we met during our first visit to Wat Xieng Thong. Destination: the Pak Ou caves. We got up early enough to pause at the bakery for our morning breakfast before meeting him just before 9 o'clock.

We climbed down the stone steps to the river bank where he and his wife maneuvered their 12-seat, 30 foot sampan into position with their oars gliding them through the muddy water. We stepped into the boat and headed north, cruising through the waters as a heavy fog loitered over the surrounding mountains. I loved the fresh breeze hitting my face but the rush of cruising peacefully up the Mekong faded as I realized I was not padded with sufficient layers of clothes to keep warm. Susanne, ever more practical than I am, pulled her pocket anorak and sweater out of her backpack and enjoyed a comfortable ride upriver. Meanwhile, I shivered and hoped for the sun to break through the clouds and warm my chilled bones.

into position with their oars gliding them through the muddy water. We stepped into the boat and headed north, cruising through the waters as a heavy fog loitered over the surrounding mountains. I loved the fresh breeze hitting my face but the rush of cruising peacefully up the Mekong faded as I realized I was not padded with sufficient layers of clothes to keep warm. Susanne, ever more practical than I am, pulled her pocket anorak and sweater out of her backpack and enjoyed a comfortable ride upriver. Meanwhile, I shivered and hoped for the sun to break through the clouds and warm my chilled bones.

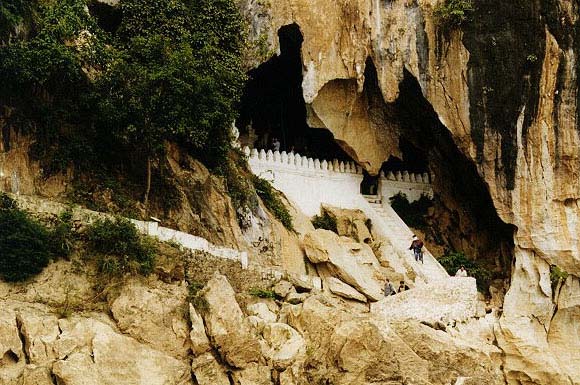

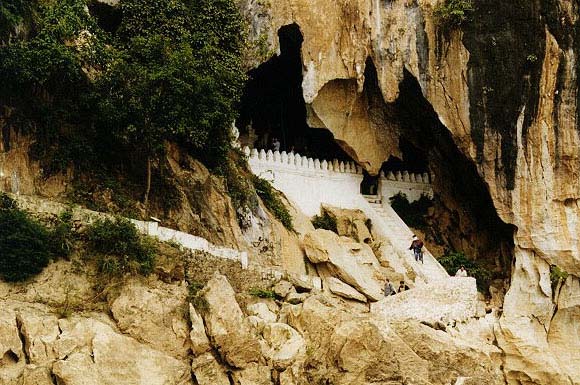

We motored through the morning waters for over 90 minutes when I noticed a large sheer cliff hanging ahead of us. As we got closer the cliff got higher and higher, probably upwards of 1000 feet. But before we reached the base of the cliff the boatman slowed the motor, for I had neglected to notice the mouth of the Pak Ou caves on the left bank of the Mekong. From the boat I could now see the gaping entrance of the limestone cave, with polished white steps leading up from the riverbank. Inside the cave were shadowy, almost alien figures, staring out at me from the distance. These faces were but a few of the many Buddha statues that made Pak Ou famous.

|

| Entrance to the Pak Ou Caves |

For centuries, the Pak Ou caves - the lower Tham Ting cave and the upper Tham Phum cave - were sacred sites to local animist tribes. But when northern Laos converted to Buddhism by the 14th century, the caves too were converted, and by the mid 1600s the kings of Lane Xang were making pilgrimages here to pay respect to the thousands of Buddha images inside. These royal pilgrimages continued each year until 1975. Despite the loss of royal patronage, Tham Ting and Tham Phum remain an important sacred shrine in Lao Buddhism.

|

| Buddha statue, Pak Ou Caves |

We jumped out of the boat on to a floating bamboo platform that allowed us to step to dry land. We then paid the resident attendant the 500 kip entrance fee and climbed the stairs to Tham Ting. The caved echoed with the sounds of swallows that made their home deep inside, far away from where we'd be allowed to enter. Buddha statues of all shapes and sizes occupied the cavern, many covered in candle wax, facing the open mouth of the cave. It was an unusual blend of the geological and the mystical - an eons-old cave with its primeval timelessness, the eternal gaze of the Buddhas contemplating the universe and all of its complexities - I could see how a monk could spend months here if he wanted to.

There was a long climb of steps to reach the Tham Phum cave. Though not as visually stunning as Tham Ting, Tham Phum is more subtle, more surreal. An old teak gate welcomed us at the cave's entrance. Once inside, all was dark save a few small candles scattered about the cave. As we walked the 200 feet into the cave, we soon needed the aid of the small flashlight I had packed. First time in three trips I had actually used it, actually. From the light of my torch we could see several hundred Buddha images ranging from just a few inches tall to more than life size. Each Buddha was a surprise lurking in the darkness, popping into view like a ghoul in a haunted house. There was nothing particularly ghoulish about the statues themselves, but their shadows danced on the high cave walls, the rhythm of their motion determined by the baton movements of my flashlight. Shadows from a single Buddha statue multiplied when other visitors targeted their lights at it, causing random afterimages on the wall - a ghost of a ghost of a Buddha, if you will. The cave conjured images of Halloweens past - not exactly what I had expected from such a holy Buddhist shrine. Perhaps some of this was meant to show that even the Buddha could have had a sense of humor. Who knows.

We paused for a Coke and a rest room stop before returning to the boat. Our boatman steered the craft closer to the cliff on the eastern shore. Beyond the cliff was the mouth of the Nam Ou river, which joins the Mekong at this intersection. I imagined trekkers from Colorado scaling the face of the cliff as part of some REI-sponsored expedition - perish the thought. The boat then doubled back south down the Mekong. Our final scheduled stop was a Lao village known as Ban Xiang Hai, the Jar Maker Village. For generations, villagers here created the jars used for storing Lao-Lao, a popular, semi-illicit moonshine made with fermented rice. Archaeologists apparently have found shards of jars dating back nearly 2000 years, suggesting that these folks really knew what they were doing when it came to jars. Lately, though, the locals have started to buy ready-made jars from elsewhere and focused on brewing and bottling Lao-Lao instead.

|

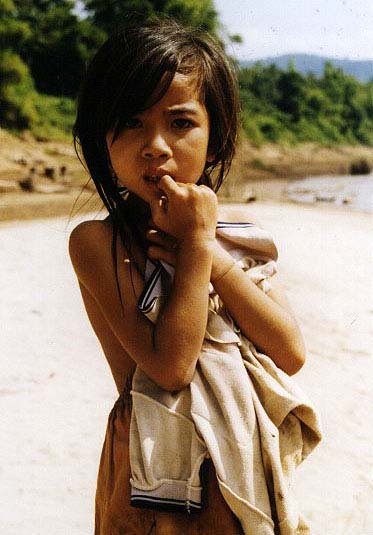

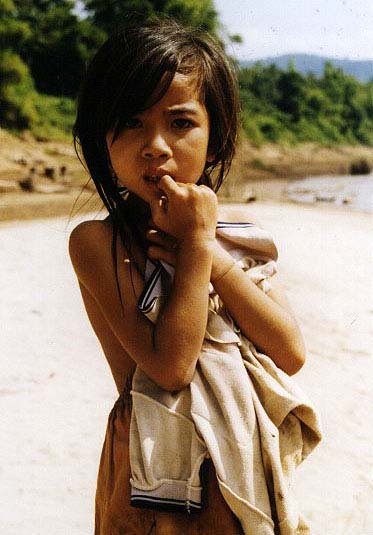

| Lao Girl, Jar Maker's Village |

We were met on the beach by eight or nine young children, all eager to pose for pictures for the right amount of kip. They were the only children we encountered in all of Laos who demanded tips for their cuteness. When we realized they wanted money, we stopped taking pictures because we didn't think it was appropriate for kids to be touting for a quick kip in this manner. Above the beach and in the village we found numerous stilt houses opened up and selling souvenirs of all types. A large group of French tourists were herded around like cattle, many of them handing out 1000 kip notes to the kids for no apparent reason. This is how it all begins, I thought. It starts as a village that opens itself up to visitors to help sell some goods, but it ends up becoming just another tourist trap fully dependent on farang visitors with handouts.

I steered around the tour group and followed our boatman, who brought me to a friend's hut that offered free samples of Lao-Lao. He handed me a shot glass of the clear liquid and said in French it was "le distillant de riz blanc fermentee." I swallowed the moonshine, let out a resonant, tubercular cough and replied, "Le distillant de petrol, peutetre!" He laughed and offered me a second shot, which I declined politely as my eyes glazed over. The boatman then handed me another glass, this one containing a syrupy red liquid with the consistency of cough medicine. "Fermentee riz noir et sucre," he explained. I struggled to remember the name of the traditional rice wine popular in northern Laos. "Lao khao... Lao khao...," I started to say. "Oui, Lao khao kam," he replied. "Dee lai lai!" I swallowed the shot and immediately thought of cough syrup again. Actually, it wasn't that bad, but the wine left a stale rice aftertaste that almost had me longing for another shot of Lao-Lao. The boatman's friend offered me a bottle, which I could take home for only 2000 kip. Tempting, but I decided to cherish the memory instead.

I paced through the village with the boatman, watching all of the French tourists crowd around one souvenir stall after another. "Beaucoup Farangset," I said to him in a weird French/Lao melange that for the moment came naturally to me in his presence. "Mai dee lai." "Not good for you, peutetre," he said back in Franglais, "mais tres bon pour les villages." This was an argument I knew I didn't want to get into, especially with a man who spoke at least three languages better than I spoke one. "D'accord, okay," I replied, and left it at that.

Once the French had cleared out, I stopped at a stall run by two teenage Lao girls. They were selling a variety of knick-knacks including small wooden statues of Pu No, one of the pre-Buddhist pagan spirits associated with the founding of Luang Prabang. Pu No had a big, round cartoon face with a huge mane of rope dreadlocks that covered its entire body - sort of an animist Lao Oscar the Grouch. One of the girls asked for 7,000 kip, and I soon got her down to 5,000 for one of them. I bet it would look good on my desk at work.

|

| Our boatman on the Mekong |

As we returned to the boat, I asked our guide if he knew what it would cost to catch a speedboat for the 300km ride up the Mekong to Huay Xai, at the Lao-Thai border. He didn't know the answer offhand but he agreed to take us to the speedboat landing north of town to find out how much it would cost. Twenty minutes or so into our ride we pulled along side the speedboat docks. I expected he would let me climb out of the boat and up the earthen steps to talk with the speedboat drivers atop the cliff. Instead he yelled out to them in Lao and had a brief exchange with several other boatmen at the top of the cliff. "When do you want to go?" he asked me. "Tomorrow," I said. "Meueun," he yelled up to the boatmen. They shouted back and forth for a few moments until he turned to us and said, "OK, tomorrow I take you here at 8am, you pay 30,000 kip per person, you go to Huay Xai in six hours. OK?" That was less than $18 each - fair enough. We agreed to be there at 8am the next day, and the boatman would give us a ride back to the speedboat pier.

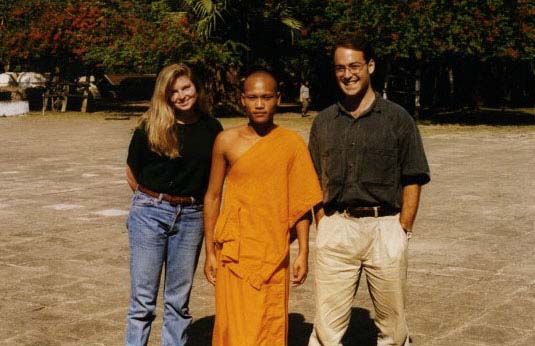

Back at the docks by Wat Xieng Thong, we disembarked and paid the boatman 30,000 kip for the tour - 25,000 for the ride plus a 5,000 kip tip. He thanked us and returned to his boat, reminding us to be there the next morning. I figured we'd get some lunch soon but first we decided to visit the wat to see if we could find our young monk friend. Before we got halfway across the wat, he reappeared from a small building with a big smile on his face. "I'm sorry for the other night," he said. "I was not feeling well so I did not go to the concert." So he had stood us up, just as we had thought we had done the same to him. I felt a lot better. We told him my story of sinking into the mud that night, and we all laughed about how none of us had bothered to show up at the concert. "Did you see me last night?" he then asked. "I tried to say I was sorry then but you did not understand me." Apparently he was the monk in the orange hat. Again, we embarrassingly covered ourselves by saying, quite honestly, that we didn't recognize him with the hat and his freshly shaven head. He seemed to be sympathetic to our excuse.

|

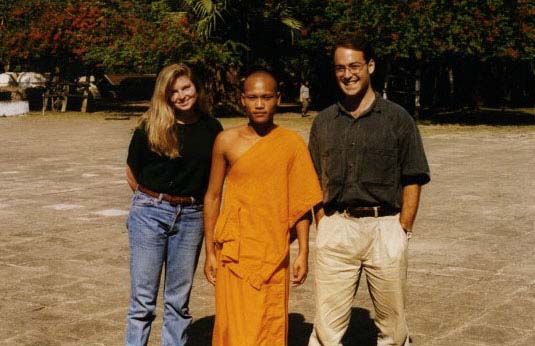

| Group Portrait: Susanne, Boua Geun and Andy |

We sat with him for 30 minutes or so, talking about America and his life at the wat. He had a brother and sister, but he doubted his brother would become a novice as well. In two years he planned to go to university in Vientiane to study law and Buddhism. He also wanted to study abroad, so he asked us if we had any English books he could read. Apart from our travel guides we weren't carrying any other books, so I offered to send him an English grammar book and some conversation tapes from America. He gave me his address - finally, a chance to see his name on paper:

Novice Boua Geun, Wat Xieng Thong. Luang Prabang, Lao PDR.

How we got Wong out of Boua Geun I have no idea. But at least we now knew his name.

Our stomachs were growling so we bid Boua Geun goodbye, promising to drop by at least once before leaving Luang Prabang. Next stop, the bakery. During this particular visit, I discovered the simple pleasures of homemade muesli with yogurt, fresh coconut shavings, pineapple, papaya and banana. I wanted to kick myself for all of those days wasted on banana bread.

We promised ourselves a lazy afternoon so we chilled out at the hotel for a couple of hours. We returned briefly to Wat Xieng Thong in a feeble attempt to sketch pictures of the main sim, but we found the architecture too complex and the sun's heat too ruthless. Boua Geun reappeared and applauded us for the effort. He soon returned to his studies, so we decided to head off and get dinner.

Another evening at the Villa Santi. It began on a clumsy note as I knocked a salt shaker and a box of toothpicks off the table and down from the balcony to the grass below. No injuries. For dinner, we again ordered spring rolls and the mushroom soup, and split an entree of minced chicken with basil for our main course - the first boneless white meat chicken of our entire trip. We bumped into Keith, the 45-year-old New Yorker we had met at the bakery yesterday. We invited him to join us, and we spent the better part of the evening listening to him tell tales of go-go bars and Thai boxing shows in Chiang Mai, smoking bad opium with hill tribes, and why American marijuana was better than its southeast Asian counterparts. Clearly here was a man with a mission in Laos, a man who had taken us as fellow pharmacological aficionados. Maybe not, but his stories were still quite funny.

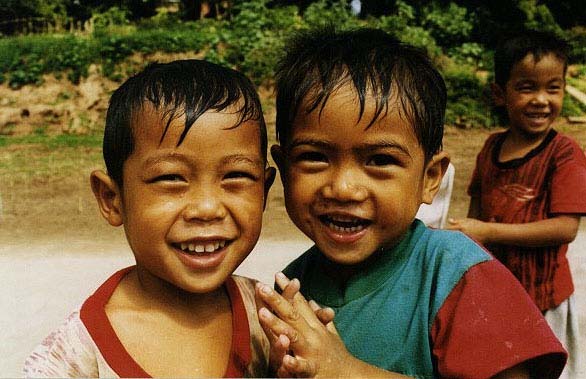

After dinner we decided to walk back to the hotel, hoping to say goodbye to those two cute kids we had played with the night before. Like clockwork, we found them resting on a small table in front of grandma's shop, half asleep. The little girl was pretty groggy and kept drifting back to sleep, but the boy got up and gave my leg a big hug, slapping my hands when I held my palms out. I tried it again, and this time he fell forward, putting his entire weight on my hands, closing his eyes. Definitely nappy time for this little one. Grandma smiled and told him to wave bye-bye as we left. "Bye-bye!" he said in English, "Bye-bye!" A fitting farewell for a city of children we had gotten to know so well.

into position with their oars gliding them through the muddy water. We stepped into the boat and headed north, cruising through the waters as a heavy fog loitered over the surrounding mountains. I loved the fresh breeze hitting my face but the rush of cruising peacefully up the Mekong faded as I realized I was not padded with sufficient layers of clothes to keep warm. Susanne, ever more practical than I am, pulled her pocket anorak and sweater out of her backpack and enjoyed a comfortable ride upriver. Meanwhile, I shivered and hoped for the sun to break through the clouds and warm my chilled bones.

into position with their oars gliding them through the muddy water. We stepped into the boat and headed north, cruising through the waters as a heavy fog loitered over the surrounding mountains. I loved the fresh breeze hitting my face but the rush of cruising peacefully up the Mekong faded as I realized I was not padded with sufficient layers of clothes to keep warm. Susanne, ever more practical than I am, pulled her pocket anorak and sweater out of her backpack and enjoyed a comfortable ride upriver. Meanwhile, I shivered and hoped for the sun to break through the clouds and warm my chilled bones.