8am, Bangkok's Don Muang International Airport, departure gate 41. I'm sitting at the only gate that has free seats available. To my right an anxious crowd gets ready to board a flight to Singapore. Just beyond them it's mayhem as people vie for standby tickets to Ho Chi Minh City. But here at Gate 41, I've got all the stretching room I need, because through the doors just ahead of me sits a Royal Air Cambodge ATR 72 bound for Phnom Penh. I wonder if we'd be the only people on this flight. Perhaps we were indeed crazy for even wanting to go in the first place.

But this was a trip I had to make. Ever since seeing the film 'The Killing Fields' years back I've struggled with answering the difficult question of how on earth an entire nation could literally commit suicide. Suicide. Our world is full of countless histories of atrocity, where one culture vents its wrath on another culture. This century alone, we've witnessed Jews, Armenians, Roma, Bosnians, Tutsis, just to name a few, led to their deaths for reasons no more logical than hate or fear itself. Yet in Cambodia, there was no dominant ethnic group oppressing a minority, no country wiping out its neighbor in the name of nationalism. In Cambodia, Khmers killed other Khmers, first over political struggle, then over social ideology, and finally over bloodlust and paranoia as ends in themselves. This small Asian nation not much larger than the state of Missouri exterminated as many as two million of its own brothers and sisters. Two out of seven Khmers starved or murdered in less than 45 months: April 17, 1975 to January, 1979.

As a Jew I've always struggled with the legacy of the Holocaust, and over time I've begun to understand just how Germany could have committed such an egregious crime against humanity. As abhorrent as the Holocaust was, from a strictly historical and disinterested perspective I can understand the chain of events that led to it. Same thing in Bosnia and Rwanda - terrible events, though not entirely unpredictable. But Cambodia made no sense to me. How any country could perpetrate in my lifetime a crime so hideous as to have 11-year-old boys literally executing their own parents with a blow of a shovel to the back of their heads, all for the "capitalist" crimes of speaking French, wearing glasses, being a teacher, was beyond my scope of understanding. I had to experience Cambodia as a nation, as a people, as a culture, just to begin to understand it.

Right now, I'm flying at 15,000 feet over western Cambodia, on our way to Phnom Penh. It's a beautiful day, and I can see dense forests below. I thought I'd be uneasy at this particular moment, but I'm actually quite excited. Back in Bangkok, our travel agent had made arrangements for a guide to pick us up at the airport and take us around for the day, so we'd never have to worry about being alone. There are about 30 people on our flight - Thais, Khmers, Japanese, Indians, even a few Americans. I had been nervous we'd be on a deserted flight. Why the hell would anyone come to Cambodia unless they had to? Well, it looks like we're not alone. Cambodia possesses one of the most unique cultures and histories in Asia, and to experience this nation, it would seem I'm willing to put my faith in humanity ahead of the obvious risks. I will be on guard for these four days in Cambodia, but I will enjoy it. Damn it, I will enjoy it.

It's 10:30am, and our plane is descending into Phnom Penh. I've filled out my visa application and customs form. There's no turning back now. Like it or not, within the hour I'll be on the ground in Cambodia.

The plane completes a rather bumpy landing in near-perfect weather - 80 degrees, crisp and dry, sunny. Thank goodness for the end of the southeast monsoons earlier this week. Pochentong International Airport is no larger than an American municipal airport. The arrival lounge is clean and orderly, a surprise considering that artillery shells decimated the control tower and radar system four months ago. Inside the terminal we queued through a line of immigration officers who sternly examined our visa applications and passports. At the end of the queue, a young female officer looked up at me and gave me a beautiful Khmer smile, a singular gesture that cut through so much of the residual doubt and weariness in my head.

Having paid the $20 dollars cash required for the visa stamp, Susanne and I completed immigration, breezed through customs and made reservations at the tourism desk for a downtown Phnom Penh hotel. The Hawaii Hotel was a three-star located near the Central Market, and at $42 a night it was well above our usual hotel budget. But Cambodia was still near the top of the U.S. State Department Traveler Advisory List: kidnapping and murder of Westerners was not unheard of here, so we decided to ere on the side of caution. First, though, we needed to meet our guide for the day, whom we had hired through the MK Ways travel agency in Bangkok. We were expecting a man to greet us with our names on a placard, but outside we could only find a horde of young and eager taxi drivers, all of whom shouted for our attention. We remained inside the terminal, away from all of the ravenous touts, and waited. After 10 minutes of mild concern, we saw a smiling young man holding a sign bearing our names - it was welcome relief. We introduced ourselves to the guide; his name was Rith (pronounced like the word 'writ') and he was 29 years old - a bit of a shock for he didn't look a day over 21. We informed Rith of our reservations at the Hawaii Hotel, so he gathered our car and driver for the short drive to downtown Phnom Penh.

|

| Susanne crosses the street towards the Central Market |

Phnom Penh is alive with people. A city of around one million residents, yet I doubt there are any buildings in town that are over four or five stories tall. Motorcycles and scooters whiz by in packs like bicyclists in Beijing. There are so many cars and people moving about, yet I wouldn't go so far as to describe it as traffic, especially after having experienced the hellish gridlock of Bangkok. The moldy whitewash buildings look warn and tired, yet still possess an eerie French Colonial ambiance. A ghost town repopulated, quite literally. I wondered if the streets of Port au Prince or Dakar ever felt like this. Many of the streets are potholed or unpaved, and there are no working traffic lights, yet nearly every car I see is a Toyota Camry, a Honda Accord, or a new model Nissan pickup truck. Here was a city a hair's width away from anarchy, yet its assortment of automobiles were more akin to American suburbia. A first of many paradoxes, undoubtedly.

But beyond the dustiness of the streets and the peeling white paint, Phnom Penh was bright and vivacious as sunbeams shone off turn-of-the-century villas along treelined boulevards. The people here went about their daily business in a cheerful way, despite the decades of suffering and despair. A bicycling boy in a school uniform rides by, ringing the bell on his handlebar to compete amongst the motorscooters. Well dressed teenage girls sharing a cyclo taxi covertly point and giggle at young men while waiting to turn at an intersection. Men talk on cellular phones and scoop heaping spoonfuls of curry and rice into their mouths at a streetside cafe. This is not the Phnom Penh I expected.

Rith dropped us at the hotel and we agreed to regroup in two hours, around 2pm. This would give us time to freshen up and eat lunch, but we hadn't anticipated being out of our guide's protective reach for any length of time that day. At first we contemplated holing up at the hotel, but Susanne and I agreed that it was certainly safe enough to visit the Central Market as long as we looked out for each other and used some common sense. We locked up our valuables in the room and with only our cameras in hand, we walked outside and strolled to the market.

|

| Cyclo taxis, Phnom Penh |

The sky was bright and blue as men approached us on three-wheeled cyclos, motioning to see if we wanted to hire them for a ride. I'd motion back to say no, and in most cases, they would pedal away, with only one or two of them pestering us for patronage. We had to dodge the traffic to cross 53rd street - no stoplights in town makes this an adventure every time - in order to reach the outer stalls of the Central Market. Rows of fresh flowers and vegetables greeted us on our right, while to the left women squatted over small charcoal fires to tend to roasting peanuts and chestnuts. Many of the stalls were devoted solely to touristy items like t-shirts ("I survived Phnom Penh", "Tintin in Cambodia," "Danger: Landmines"), Angkor paperweights and small Buddha statues, so considering the current dearth of visitors to Phnom Penh, I wasn't at all surprised by the continuous calls in French and English beckoning us to visit their shops. I paused at one stall where a lovely girl, perhaps 10 years old, was selling kramas, those ubiquitous checkered cotton scarves you see Khmers wearing in all types of weather. I was interested in buying a krama, so I asked how much they were. One dollar each for the big ones, three for two dollars for the smaller ones, she said (Cambodia is largely a U.S. cash-only economy thanks to consistent inflation that has brought the Cambodian riel down to 3600 riels per dollar). I wasn't ready to buy anything just yet, so I made a mental note to return here on my way out and told her I'd be back. I guessed from the look on her face that she heard that a lot from Westerners.

At the center of the stalls is a large orange building with a roof of concentric circles thinning out into a pyramid. "An art deco ziggurat," in the words of the Lonely Planet guide. We entered the building and were amazed to find a brilliantly lit arcade of gem sellers, wristwatch dealers, makeup counters and perfume shops. Cambodia's answer to Macy's. But as we wandered awestruck through the aisles, the sobering reality of Cambodia set itself upon us. A young boy, perhaps 12 or 14, ragged, half blind and with a noticeable limp, began to follow us around with his arms outstretched. "Papa, monsieur. Mama, madame. Papa..." he chanted, his blank, sunken eyes staring at us. I tried to ignore him, for I knew that giving alms in such a public place would take the finger out of the dike and release a flood of needy street urchins upon us. So we began a sad, sad game of cat and mouse as we tried to lose him in the maze of stalls. But it was to no avail for he would keep up with every turn, arms outward, "Mama, Papa..." Susanne noticed that he would back off when we neared the policemen sitting around the market entrance. So I visited the counter closest to the police, feigning interest in some jewelry. The poor wretch darted away, fearing retribution from the cops. Meanwhile, I pointed at a piece of ivory sitting in the gem case, asking the saleswoman what it was. She handed it to me as I realized it was a tiger's canine. "Very cheap, monsieur," she said. "You buy, yes?" Embarrassed and a bit saddened that I hadn't recognized what it was, I handed it back to her and declined politely.

Susanne and I returned to the young girl with the collection of kramas. I selected two scarves: a black and white and a red plaid with yellow threads. As I removed two dollars from my pocket, another wave of beggars surrounded us, most of them amputees from landmines. They were the first of many amputees I'd see in my short stay in Cambodia, a country where one out of every 250 people had been maimed by landmine explosions. I handed the two dollars to the girl and thanked her - "Aw kohn," the only Khmer I knew at this point. The beggars got very close to me and pressed at my arms and shoulders. "Monsieur, monsieur," they said in unison. I thought to myself: even if I did give them the couple of dollars in my pocket, it wouldn't change anything. I couldn't save these poor souls even if I tried, so I closed my eyes, swallowed hard and walked away, not looking back. We crossed the road back to the hotel, with me left feeling a little blank and unsure.

|

| The Silver Pagoda, Phnom Penh |

Rith and our driver met us downstairs at 2pm. Our first destination was the Silver Pagoda. The Pagoda was part of the King's palace compound, but the rest of the palace has remained closed to the public ever since King Sihanouk returned to the throne a few years back. Through the compound gates we found a glorious courtyard bedecked with stone stupas and golden pagodas of all shapes and sizes. This was Phnom Penh at its proudest. The pagoda was built in 1892 by King Norodom, Sihanouk's great grandfather, as the eternal residence of Cambodia's Emerald Buddha, a Baccarat crystal statue modeled after the Emerald Buddha at Wat Phra Kaew in Bangkok. The pagoda's main courtyard is used for the interment of royal ashes under its stupas. We circled the Silver Pagoda, marveling at its size and glistening panels. Inside, Rith noted that the floor was constructed entirely of solid silver tiles, over 5000 of them, each weighing more than a kilogram. At the center of the temple was a golden shrine for the Emerald Buddha. In front of it, though, stood a sight even more impressive - a solid gold, life-sized Buddha statue weighing nearly 200 pounds. Beyond my initial shock over its mere existence, I was puzzled as to how on earth this treasure could have survived the destruction of the Khmer Rouge.

returned to the throne a few years back. Through the compound gates we found a glorious courtyard bedecked with stone stupas and golden pagodas of all shapes and sizes. This was Phnom Penh at its proudest. The pagoda was built in 1892 by King Norodom, Sihanouk's great grandfather, as the eternal residence of Cambodia's Emerald Buddha, a Baccarat crystal statue modeled after the Emerald Buddha at Wat Phra Kaew in Bangkok. The pagoda's main courtyard is used for the interment of royal ashes under its stupas. We circled the Silver Pagoda, marveling at its size and glistening panels. Inside, Rith noted that the floor was constructed entirely of solid silver tiles, over 5000 of them, each weighing more than a kilogram. At the center of the temple was a golden shrine for the Emerald Buddha. In front of it, though, stood a sight even more impressive - a solid gold, life-sized Buddha statue weighing nearly 200 pounds. Beyond my initial shock over its mere existence, I was puzzled as to how on earth this treasure could have survived the destruction of the Khmer Rouge. As Rith explained, the answer was quite simple. The Khmer Rouge had a public image to protect among the international community, despite its attempts to isolate Cambodia from the rest of the world. So they kept the Silver Pagoda as a token conservation effort, just in case foreign dignitaries might want to visit it. Nevertheless, the gold and crystal Buddhas were still quite lucky, for more than half of the other priceless relics kept at the Silver Pagoda were destroyed by the Khmer Rouge.

As Rith explained, the answer was quite simple. The Khmer Rouge had a public image to protect among the international community, despite its attempts to isolate Cambodia from the rest of the world. So they kept the Silver Pagoda as a token conservation effort, just in case foreign dignitaries might want to visit it. Nevertheless, the gold and crystal Buddhas were still quite lucky, for more than half of the other priceless relics kept at the Silver Pagoda were destroyed by the Khmer Rouge.

Rith led us to a tree-enshrouded hill, an earthly representation of the mythological Mt. Meru

Rith led us to a tree-enshrouded hill, an earthly representation of the mythological Mt. Meru (the nexus of time and space in Hinduism and Khmer Buddhism). A group of Khmer schoolchildren was playing there and we soon caught their attention. Next thing I knew, we were posing for pictures together, laughing over their bad English and our worse Khmer. Eventually it was time to move on so we returned to the car, were approached once again by an amputeed beggar in military fatigues. The car drove off before he could get very close, though, as he struggled across the road on one crutch.

(the nexus of time and space in Hinduism and Khmer Buddhism). A group of Khmer schoolchildren was playing there and we soon caught their attention. Next thing I knew, we were posing for pictures together, laughing over their bad English and our worse Khmer. Eventually it was time to move on so we returned to the car, were approached once again by an amputeed beggar in military fatigues. The car drove off before he could get very close, though, as he struggled across the road on one crutch.

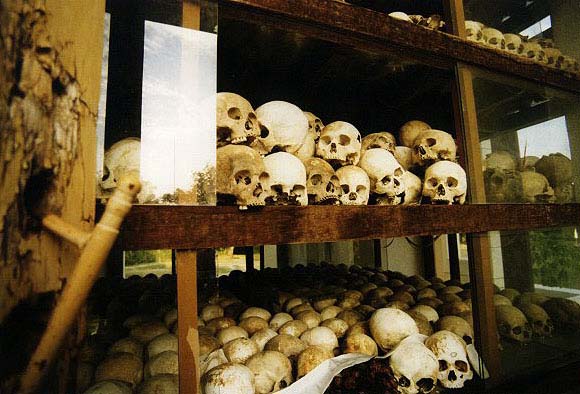

Our next stop was Tuol Sleng, the infamous S-21 interrogation center of the Khmer Rouge. Before 1975, Tuol Sleng was a typical Phnom Penh high school. From 1975 to 1979, though, it was without a doubt the most horrible place on earth. Within these walls, 17,000 prisoners, including entire families, were incarcerated, interrogated and tortured here, all for the soul purpose of extracting confessions from them before execution. Of the 17,000 inmates who entered Tuol Sleng, only seven people - seven - are known to have survived. The rest of them either died inside or met their fate in the killing fields of Choeung Ek, just outside of town.

|

Wooden gymnastic beams used by

Khmer Rouge for hanging and torture |

My first impression of Tuol Sleng was its familiarity - it reminded me quite vividly of my own high school in Florida, which was built in a similar outdoor courtyard style. As I looked around I saw my own high school draped in barbed wire, with the gasps, moans and screams of the damned emanating from inside. I was snapped out of this ghoulish daydream when Rith introduced us to Phalla (pronounced "Palla"), a Khmer woman who would be our guide. Phalla appeared to be in her mid 40s and she had a round and freckled complexion with almost Polynesian features. Immediately I wondered what had happened to her during the Khmer Rouge years - she would have been in her mid-twenties at the time, perhaps my age or younger. But I knew this wasn't the moment to ask such things; maybe she would tell us in the course of the tour.

On the far left end of the courtyard, Phalla showed us the graves of the last 14 victims of Tuol Sleng. They were all killed in the days and hours leading up to the successful occupation of Phnom Penh by the Vietnamese in early January of 1979. Condemned internationally as a ruthless invasion, no one in the West could have realized at the time that this occupation was tantamount to the liberation of the Nazi concentration camps by Russian forces during the waning days of World War II. Phalla brought us to a series of stark, grim rooms lit only by meager sunlight, each containing a rusty bed frame, a pair of leg shackles, plastic gas containers for urine and feces, and a large black and white photo of the victim found in that room. Cell by cell, Phalla told us in graphic detail the method of execution applied to these last victims of S-21, their throats slashed with rusty knives, their faces caved in with shovels. Each story seemed more hellish than the one preceding it. We visited five of these rooms, more than enough to visualize the horror that had taken place there. "You do not need to see them all, sir, ma'am," Phalla said to us. "I think you have seen much to understand.... Do you understand?" It wasn't a rhetorical question on her part - Phalla repeatedly asked us if we could understand her English, which was actually quite good. But each time she asked "Do you understand?" I could only hear the deeper question, "Do you see what happened here? Do you see what happened to us?" All I could do was nod my head and say "Yes," my eyes fixed on hers as if my soul depended on it.

|

| Tuol Sleng's Security Regulations |

We continued the tour by entering a complex of prison cells, cubical enclosures made of thin brick and mud plaster walls. Phalla pointed out that even a child would have the strength to knock down these walls - the plaster creaked as she pressed it with one hand - yet the prisoners of Tuol Sleng were so weak and exhausted from torture and malnutrition they rarely attempted a breakout. No will to escape. I squeezed between two of the walls to get a prisoner's perspective. I'd estimate the space was three feet wide and five feet long - not enough room to sleep flat on the floor. The air was thick and filled with dust, a million specks of dirt illuminated by horizontal rows of sunlight. Ten seconds in the cell was enough for me - claustrophobia set in as I squeezed through the wall to freedom.

The prison cells were followed by empty rooms that featured row after row of black and white portraits of prisoners. The Khmer Rouge photographed each inmate before sending them off to death by bludgeoning at Choeung Ek. The walls stared back at me: face after face of children, the elderly, mothers and babies, the beaten, the doomed. Many of them had thick metal shackles around their necks. Others had their heads propped upwards by sharp clamps, for they lacked the strength to sit up. But their faces spoke volumes. Some of them looked confused or frightened. A few even looked angry. But most of them, above all else, looked totally hopeless. Hopeless from having accepted the fact that they were the walking dead, with no chance of reprieve.

returned to the throne a few years back. Through the compound gates we found a glorious courtyard bedecked with stone stupas and golden pagodas of all shapes and sizes. This was Phnom Penh at its proudest. The pagoda was built in 1892 by King Norodom, Sihanouk's great grandfather, as the eternal residence of Cambodia's Emerald Buddha, a Baccarat crystal statue modeled after the Emerald Buddha at Wat Phra Kaew in Bangkok. The pagoda's main courtyard is used for the interment of royal ashes under its stupas. We circled the Silver Pagoda, marveling at its size and glistening panels. Inside, Rith noted that the floor was constructed entirely of solid silver tiles, over 5000 of them, each weighing more than a kilogram. At the center of the temple was a golden shrine for the Emerald Buddha. In front of it, though, stood a sight even more impressive - a solid gold, life-sized Buddha statue weighing nearly 200 pounds. Beyond my initial shock over its mere existence, I was puzzled as to how on earth this treasure could have survived the destruction of the Khmer Rouge.

returned to the throne a few years back. Through the compound gates we found a glorious courtyard bedecked with stone stupas and golden pagodas of all shapes and sizes. This was Phnom Penh at its proudest. The pagoda was built in 1892 by King Norodom, Sihanouk's great grandfather, as the eternal residence of Cambodia's Emerald Buddha, a Baccarat crystal statue modeled after the Emerald Buddha at Wat Phra Kaew in Bangkok. The pagoda's main courtyard is used for the interment of royal ashes under its stupas. We circled the Silver Pagoda, marveling at its size and glistening panels. Inside, Rith noted that the floor was constructed entirely of solid silver tiles, over 5000 of them, each weighing more than a kilogram. At the center of the temple was a golden shrine for the Emerald Buddha. In front of it, though, stood a sight even more impressive - a solid gold, life-sized Buddha statue weighing nearly 200 pounds. Beyond my initial shock over its mere existence, I was puzzled as to how on earth this treasure could have survived the destruction of the Khmer Rouge. As Rith explained, the answer was quite simple. The Khmer Rouge had a public image to protect among the international community, despite its attempts to isolate Cambodia from the rest of the world. So they kept the Silver Pagoda as a token conservation effort, just in case foreign dignitaries might want to visit it. Nevertheless, the gold and crystal Buddhas were still quite lucky, for more than half of the other priceless relics kept at the Silver Pagoda were destroyed by the Khmer Rouge.

As Rith explained, the answer was quite simple. The Khmer Rouge had a public image to protect among the international community, despite its attempts to isolate Cambodia from the rest of the world. So they kept the Silver Pagoda as a token conservation effort, just in case foreign dignitaries might want to visit it. Nevertheless, the gold and crystal Buddhas were still quite lucky, for more than half of the other priceless relics kept at the Silver Pagoda were destroyed by the Khmer Rouge.  Rith led us to a tree-enshrouded hill, an earthly representation of the mythological Mt. Meru

Rith led us to a tree-enshrouded hill, an earthly representation of the mythological Mt. Meru (the nexus of time and space in Hinduism and Khmer Buddhism). A group of Khmer schoolchildren was playing there and we soon caught their attention. Next thing I knew, we were posing for pictures together, laughing over their bad English and our worse Khmer. Eventually it was time to move on so we returned to the car, were approached once again by an amputeed beggar in military fatigues. The car drove off before he could get very close, though, as he struggled across the road on one crutch.

(the nexus of time and space in Hinduism and Khmer Buddhism). A group of Khmer schoolchildren was playing there and we soon caught their attention. Next thing I knew, we were posing for pictures together, laughing over their bad English and our worse Khmer. Eventually it was time to move on so we returned to the car, were approached once again by an amputeed beggar in military fatigues. The car drove off before he could get very close, though, as he struggled across the road on one crutch.