|

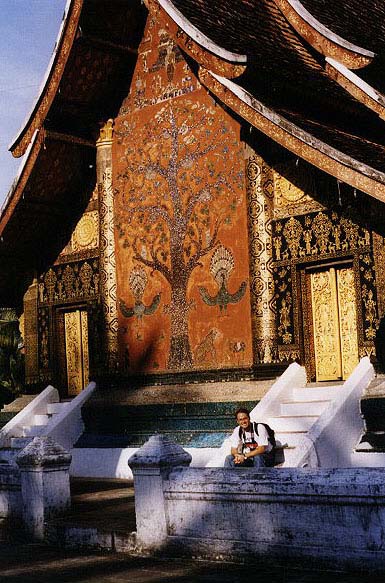

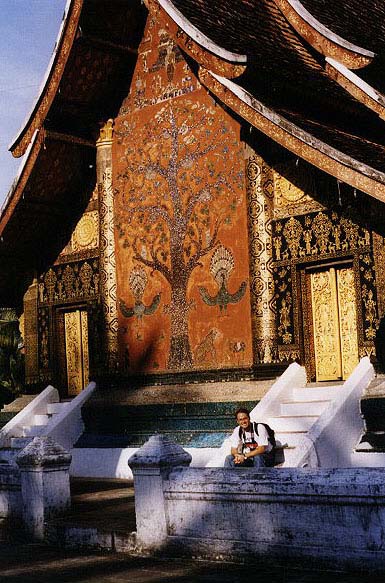

| Andy at Wat Xieng Thong, Luang Prabang |

Thursday, November 13

Luang Prabang Pilgrimage

After grabbing a baguette at the Scandinavian bakery down the road, we checked out of the Lao Paris Hotel and caught a jumbo to Wattay Airport, about 15 minutes away. Wattay reminded me of a small community airport that had been closed for a few years and then reopened without warning. It was in bad need of a shave. After some searching we found a check-in counter: a wooden table with a sign above saying Luang Prabang. I gave an official our tickets, but after a few minutes of him fondling the papers, he told me they were only good for the 11am flight. So for four hours we waited, observing a Swedish tour group munching on crackers and Lao women hoisting carry-ons of live chickens and eels in wicker baskets, slithering around like Jim Henson animatronic swamp creatures.

to Wattay Airport, about 15 minutes away. Wattay reminded me of a small community airport that had been closed for a few years and then reopened without warning. It was in bad need of a shave. After some searching we found a check-in counter: a wooden table with a sign above saying Luang Prabang. I gave an official our tickets, but after a few minutes of him fondling the papers, he told me they were only good for the 11am flight. So for four hours we waited, observing a Swedish tour group munching on crackers and Lao women hoisting carry-ons of live chickens and eels in wicker baskets, slithering around like Jim Henson animatronic swamp creatures.

At 11:15 we boarded a rickety Soviet-era Tupelov prop plane that read "Lao Aviation" in stencil block letters on the side. There was barely enough room for a dwarf's legs to fit behind each seat and the only in-flight reading was a blank air sickness bag. The plane managed to get off the ground without falling to pieces, and soon we were on our way to northern Laos and the city of Luang Prabang, the former royal capital and the spiritual center of Lao Buddhism. Susanne dozed most of the flight as I stared out the window, observing the Lao landscape as it transformed from Florida flatland to Scottish moor country to karst mountains from a Chinese watercolor scene. The texture of the land was stunning, with shards of rock and forested hillocks rising farther and farther upward. We then descended through the hills - we must be near Luang Prabang, I thought. The plane touched down with a violent certainty and I was ecstatic to get off of that Cold War antique. We paused briefly for immigration - all foreigners must register with the local police every city they visit - and then hired a jumbo to take us to the Hotel Phousi, an affordable three-star in the middle of town.

We crossed a quaint old wooden bridge wide enough only for one-way traffic and curved through the local market area, busy with more shoppers and vendors than one might expect in a town of only 16,000 residents. We soon reached our hotel, a turn-of-the-century villa that served as the French secretariat during colonial times. The jumbo drove through a wrought iron gate and past a tranquil garden cafe until we reached the hotel doors. A French family ate sandwiches in the teakwood verandah as we entered and checked into our room. The Hotel Phousi certainly seemed like a fine place to relax for a few days.

|

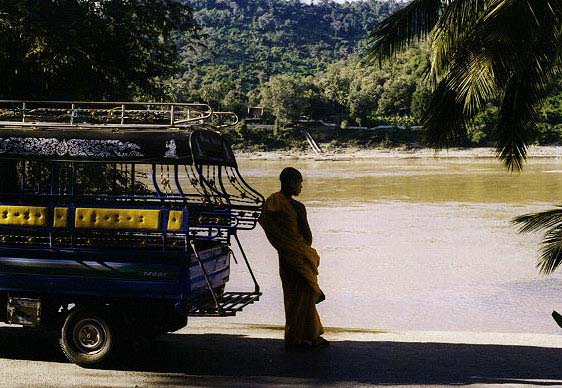

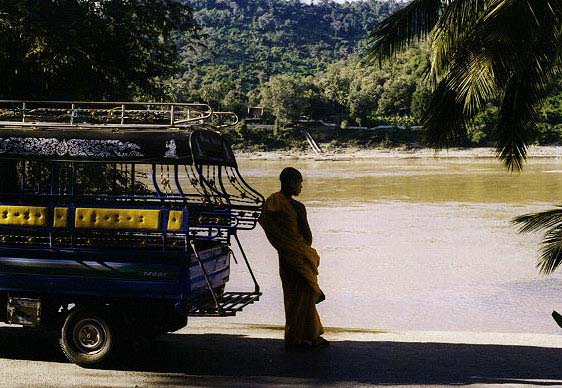

| A monk leans against a songthaew by the Mekong |

Luang Prabang is known mainly for its royal heritage and its many monasteries - over 30 wats , at least 20 of them maintained since pre-colonial times. Every street, every alley seemed to possess an intangibly regal and old-world character. Older children bicycled to and fro while younger kids played tag along the side of the road. Street vendors sold soup and noodles to passing customers (probably their neighbors). Everything had a small town feel to it; people would smile and say "Sabai dee" to us when we walked by. It was early afternoon and the sun had just passed its peak - I'd guess it was about 90 degrees outside. But that didn't deter us as we strolled the boulevard along the Mekong for the first time. About 15 feet to our left, just off the edge of the street, the earth took a steep 100 foot drop down to the river valley floor. Along the beach families tended crops in small, neatly aligned vegetable gardens as boatman plied the shoreline in their motorized sampans.

, at least 20 of them maintained since pre-colonial times. Every street, every alley seemed to possess an intangibly regal and old-world character. Older children bicycled to and fro while younger kids played tag along the side of the road. Street vendors sold soup and noodles to passing customers (probably their neighbors). Everything had a small town feel to it; people would smile and say "Sabai dee" to us when we walked by. It was early afternoon and the sun had just passed its peak - I'd guess it was about 90 degrees outside. But that didn't deter us as we strolled the boulevard along the Mekong for the first time. About 15 feet to our left, just off the edge of the street, the earth took a steep 100 foot drop down to the river valley floor. Along the beach families tended crops in small, neatly aligned vegetable gardens as boatman plied the shoreline in their motorized sampans.

The historic part of Luang Prabang is a thin peninsula surrounded on three sides by water: the Mekong and the Nam Khan (a minor tributary) cover the city's left and right banks respectively, meeting at a promontory point at the northeastern tip of the city. The Nam Khan side of the peninsula is lined mostly with farm plots, but here along the Mekong side there are small riverside cafes and intimate guesthouses with flower-covered terraces. There's a silversmith shop with its doors wide open - a handful of apprentices delicately pound out their precious crafts. I later read in the Lonely Planet book that the shop's owner was once the royal silversmith, but with the abolition of the monarchy, he's had to find new patronage with the royal family in Thailand.

Despite the outward friendliness and laid back atmosphere, I still sensed a sadness here - a residual sadness left over from the destruction of the royal family 22 years ago. For over 600 years this city was associated with the Lao monarchy, from the early days of the Luang Prabang fiefdom to the unified Laos of French colonial times. Even through most of this century, the Lao monarchy received strong public support. But soon after the Pathet Lao's consolidation of power in 1975 the communists abolished the royal court, despite promises to keep the new Lao People's Democratic Republic as a constitutional monarchy. The royal family was labeled as traitors and eventually assigned to "re-education camps" near the Plaines des Jarres along the border with Vietnam. It is believed that the king and queen died some time in the mid 1980s of starvation, malnutrition and neglect, banished to a damp cave for their final years. No one knows exactly what happened to them - they just evaporated from official public memory, without any outcry or questioning from the international community. So now some two decades after the death of the monarchy, Luang Prabang remains a town of prosperity and vitality, yet with an essential piece of its soul left for dead in some unknown northern cave.

Despite this tragic, unspoken history, Luang Prabang certainly overcomes the past by putting its best foot forward. We turned right - away from the Mekong - and found Wat Nong Sikhonmeuang glistening gold in the sunlight. It's a minor wat by Luang Prabang standards, not to mention a young one - originally built in 1729, rebuilt in 1804 after being sacked by the Thais in 1774. But it's our first wat here and the sun reflecting so powerfully off of the west side of the sim made this small wat seem so grand.

As we continued past Wat Nong Sikhonmeuang I noticed a group of kids playing in the open doorway of a house. I quietly approached them, trying to get a candid photograph. But one of the boys looked up at me and blew my cover, causing the girls to giggle and scurry behind the door, peeking their heads out from behind the teak wood frame as if to tease me and my camera. I playfully charged them, holding my camera to my face. Again they laughed and let out a giggling scream, running behind a wooden pole. The boys taunted the girls for not being brave enough to mug for the camera; eventually, some of the girls relented. An older man, perhaps one of their grandfathers, stood inside a garage just across the street, smoking his pipe and laughing while gesturing at the kids to pose for a picture. I got a few decent shots and thanked the kids: "Khop Jai, lai lai," thank you very much. "Sabai dee," they shouted back. I figured we had stumbled onto an unusually gregarious bunch of Lao children, but as we walked the streets of Luang Prabang Susanne and I concluded that outgoingness and joie de vivre was par for the course for the people of this lovely town. I could tell I was going to fall in love with this place.

As we continued past Wat Nong Sikhonmeuang I noticed a group of kids playing in the open doorway of a house. I quietly approached them, trying to get a candid photograph. But one of the boys looked up at me and blew my cover, causing the girls to giggle and scurry behind the door, peeking their heads out from behind the teak wood frame as if to tease me and my camera. I playfully charged them, holding my camera to my face. Again they laughed and let out a giggling scream, running behind a wooden pole. The boys taunted the girls for not being brave enough to mug for the camera; eventually, some of the girls relented. An older man, perhaps one of their grandfathers, stood inside a garage just across the street, smoking his pipe and laughing while gesturing at the kids to pose for a picture. I got a few decent shots and thanked the kids: "Khop Jai, lai lai," thank you very much. "Sabai dee," they shouted back. I figured we had stumbled onto an unusually gregarious bunch of Lao children, but as we walked the streets of Luang Prabang Susanne and I concluded that outgoingness and joie de vivre was par for the course for the people of this lovely town. I could tell I was going to fall in love with this place.

|

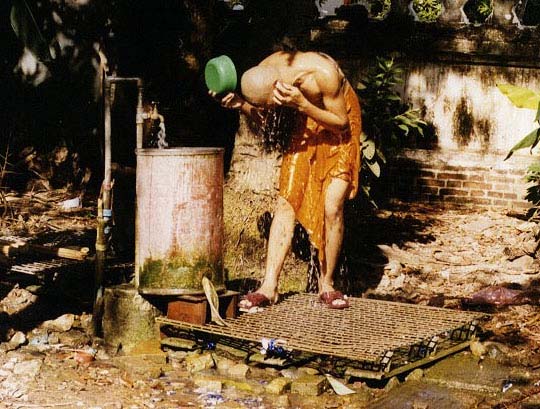

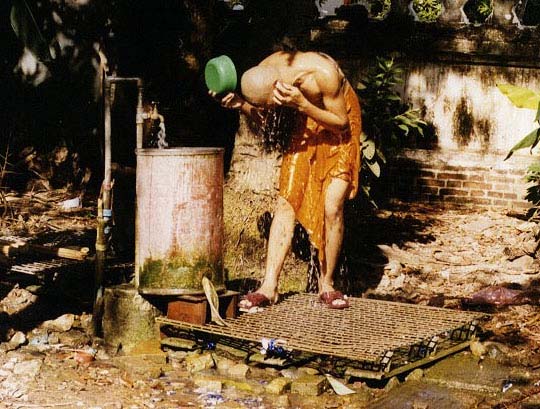

| A novice shaves his head, Wat Saen |

A block up the road we reached Wat Saen, the 100,000 Wat, so named for the 100,000 kip endowment that helped found it in 1718. Wat Saen had been refurbished in the late 1950s so it felt quite contemporary, with its many small sims looking freshly gilded, each sporting fine bronze Buddha statues inside. Behind an open-air boat house, two young novice monks at a water pump washed themselves in the warmth of the afternoon sun. Their heads appeared freshly shaven. Susanne approached them slowly - clearly this was a private moment for them, but oh, what a photo op. Then one of the novices noticed her, smiled and said, "Shiny hair" - a reference to Susanne's blondeness or their baldness, who's to say. Susanne smiled back and soon they were introducing themselves to each other. I had stood back for much of the conversation - I wasn't as bold of a photojournalist as she was - but when I saw them talking, I joined in the conversation and introduced myself. We talked for a bit and then left them to their washing. They, like many of the other young novices of Luang Prabang, were eager to practice their English. We didn't get beyond the basic smalltalk with these two but they could say more in English than I could ever say in Lao, so I was quite impressed.

Near the end of the peninsula we found the southeast gate to Wat Xieng Thong, the most venerated wat in Luang Prabang. Built around 1560 by King Saisetthathirat, Xieng Thong remained under royal patronage for the next 415 years. Its main sim is also one of the finest examples of the Luang Prabang style of architecture. Unlike the sims of Vientiane, which tend to be built tall and thin, Luang Prabang's sims are low to the ground, with two layers of sweeping tiled roofs on each side, giving it the shape of a stubby triangle from the front. The Luang Prabang style is one of the only living remnants of Laos' golden age kingdom of Lane Xang - the Land of One Million Elephants - that reigned proudly from the 16th to 18th centuries. Unlike other wats we had seen, which tended to be centered around the sim, Wat Xieng Thong was an ensemble of 12 minor stupas

of Vientiane, which tend to be built tall and thin, Luang Prabang's sims are low to the ground, with two layers of sweeping tiled roofs on each side, giving it the shape of a stubby triangle from the front. The Luang Prabang style is one of the only living remnants of Laos' golden age kingdom of Lane Xang - the Land of One Million Elephants - that reigned proudly from the 16th to 18th centuries. Unlike other wats we had seen, which tended to be centered around the sim, Wat Xieng Thong was an ensemble of 12 minor stupas , small temples, the sim itself, and a carriage house that held the processional carts used for royal funerals. While other wats crowded many buildings in whatever space was available, Xieng Thong had room to spread out and fall into place naturally like a Japanese garden, with ample space left to accentuate each building.

, small temples, the sim itself, and a carriage house that held the processional carts used for royal funerals. While other wats crowded many buildings in whatever space was available, Xieng Thong had room to spread out and fall into place naturally like a Japanese garden, with ample space left to accentuate each building.

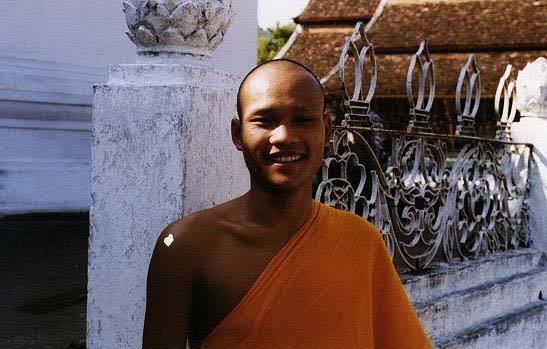

The main sim of Xieng Thong shone with the light of a thousand little suns as small tiles of colored mirrors enveloped the western wall, forming a mural of a large tree, two peacocks and numerous mystical figures. We stood around in the heat marveling the wat and its mural when a novice leaned out of the window across from the sim and said hello. He asked us where we were from and how long we had been in Laos. He introduced himself as well, but with his accent I had a hard time telling what his name was. Bu-Wong of Bu-Zhuong, perhaps. I felt bad, but didn't want to pester him to repeat it so many times.

|

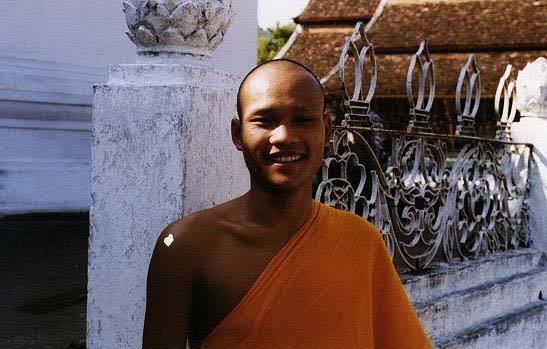

| Our new friend at Wat Xieng Thong |

He was 17 years old and from northern Sanyabuli province. "Not far from China," he said. Despite his thick Lao accent - he couldn't pronounce Susanne's name very well- his English vocabulary and grammar were quite good. He said he had only studied English for a few months, which I found shocking, but I guess that a bright young guy could pick up a lot in two or three months of intensive study. He then invited us to a concert at Wat That Luang that night, which caught us off guard, but we eagerly accepted, despite having no idea what the concert would be like or about. He told us to meet him in front of the monastery at 8pm, which I thought would work well since I wanted to try a particular Lao restaurant not far from there. We talked a little while longer and then said goodbye, looking forward to see him at the concert that night.

|

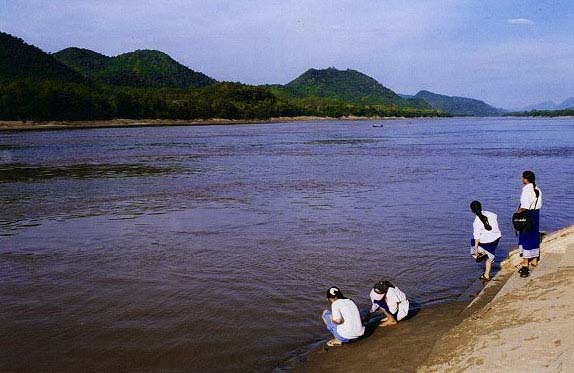

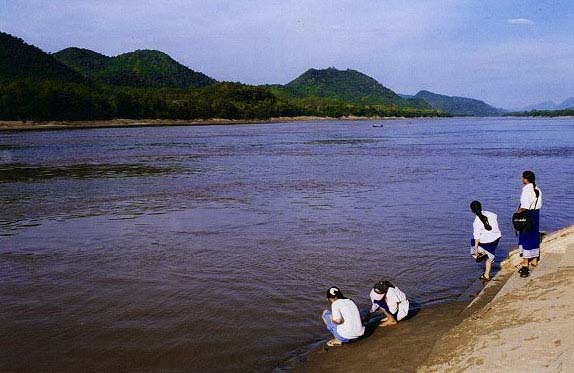

| Schoolgirls playing along the Mekong |

On the northern side of Xieng Thong we found a high row of stone steps leading down to the Mekong river. I walked down to the shore, where a group of four teenage girls in blue school uniforms sat on a sand bar and tossed rocks into the water. One of them turned and saw me. She quickly pulled her friends into a huddle and started to whisper and giggle. One of them started to talk rather loudly, saying "mon cheri, je t'aime," and then "Oh yes, I love you, yes," while the others laughed hysterically. They looked back at me to see if I was embarrassed. I blew them a kiss instead. They screamed in surprise and started to laugh even more. A minute or two later some boys pulled up on a large sampan. The entire group then climbed up to the road and headed into town.

Back up top I found Susanne, who was sitting on a marble banister admiring the view. A thin, middle aged Lao man approached us and asked me in perfect French, "Parlez-vous Francais, monsieur?" "Un peu," I responded, "mais je prefere Anglais. "If you prefer English, that's fine," he said, switching languages with ease. "Would you like to go to Pak Ou caves? 25,000 kip." That was about 15 dollars, not an unreasonable price. Younger boatmen had pestered us before about visiting these famous Buddhist shrines 25 miles upriver, but I liked this man's laid back nature, so we accepted his offer. 9am Saturday sounded good at the time, so we planned to meet him then.

Back along the boulevard along the Mekong we stopped at a small wooden cafe for a short rest. We ordered some Cokes and enjoyed the view over the river, watching sampans going by and naked children joyously prancing at the water's edge as the sun sank lower in the southwestern sky. One of the waitresses was having a few drinks with two men. The three of them had already put away six one-liter bottles of BeerLao, the national drink, and they seemed deeply engrossed in discussing the day's gossip. I stepped down to the balcony to admire the view over the river. Every time I looked back at the table, I caught sight of one of the two Lao men in the corner of my eye. He was smiling brightly at me, as if to say "I'm so glad you're enjoying my home town." In all of my travels I'd never felt that kind of genuinely welcoming presence before, and it made me feel all the more comfortable in this distant, unknown land.

After polishing off our Cokes we returned to the hotel for a much needed shower and change of clothes. Everything we had to wear smelled terribly so we committed to doing laundry the next day, no matter the inconvenience of having to buy some t-shirts just so we'd have some clean clothes to wear. We then caught a jumbo to Malee Lao Food, a friendly Lao restaurant just southwest of the old town. Even though it was an open air restaurant, the tables and walls were free of pests, not including the ever present geckos that we always regarded as signs of good luck. In the back corner of the restaurant Malee's children huddled around a television watching a Chinese import soap opera Kung Fu adventure flick. I felt like we were eating in Malee's Living Room, but that was okay.

Susanne and I split a large bottle of BeerLao - surprisingly tasty and refreshing, we thought - as we snacked on a couple of small bananas while waiting for the main course. For dinner we had a plate of ginger chicken, thick chunks of ginger and bony dark meat chicken that was flavorful but somewhat disappointing; chicken laab, a Lao specialty of ground meat, watercress and mint, lightly sauteed but practically raw- very good but risky from a gastrointestinal point of view; and sticky rice, the ever present, super glutinous Lao rice served in steam baskets. I noshed on the laab and peeled off fingerfuls of rice, rolling it into a ball with one hand and dipping it into the entrees, as is the Lao custom, while Susanne pragmatically used her fork with much more success. We also ordered a backup of tam yam gai, spicy chicken soup with lemongrass that's usually a safe bet. This time the soup contained a pasta-like substance that fanned out in the shape of a poppy flower - I couldn't tell if it was a plant, a piece of chicken skin, or what - but it was really delicious.

After dinner we walked down the road to the That Luang monastery to find Bo-Wong or whatever his name was - boy, I really felt bad about not knowing his name. Maybe I'd find a polite way to ask him again or even write it down for us. It was dark and the monastery was hidden deep behind a large field which we approached cautiously. As we navigated the compound I felt my left foot sink deep into the ground - I had stepped into a swamp- and my hiking boots, socks and my only pair of clean trousers were enveloped in thick, warm, gooey mud. "Jesus Christ!" I hissed, almost ready to throw my camera into the ground. I saw a monk rinsing his plastic sandals and feet under a water pump. He looked at me and gave me a classic Asian giggle of embarrassment, shaking his head back and forth. In that singular moment of clarity, I understood the wisdom of wearing sandals instead of Nikes. The monk continued to smile in humorous disappointment. I could feel my socks drip with warm dampness - there was no way I could handle a concert in this condition.

Upset over my troubles, we caught a jumbo back to the hotel. I washed off my shoes and trousers in the shower, hoping that the brave hotel laundry staff could repair the damage done. And I hoped that our young monk friend would forgive us for standing him up, if we could only find him the next day. And if I could only remember his name...

to Wattay Airport, about 15 minutes away. Wattay reminded me of a small community airport that had been closed for a few years and then reopened without warning. It was in bad need of a shave. After some searching we found a check-in counter: a wooden table with a sign above saying Luang Prabang. I gave an official our tickets, but after a few minutes of him fondling the papers, he told me they were only good for the 11am flight. So for four hours we waited, observing a Swedish tour group munching on crackers and Lao women hoisting carry-ons of live chickens and eels in wicker baskets, slithering around like Jim Henson animatronic swamp creatures.

to Wattay Airport, about 15 minutes away. Wattay reminded me of a small community airport that had been closed for a few years and then reopened without warning. It was in bad need of a shave. After some searching we found a check-in counter: a wooden table with a sign above saying Luang Prabang. I gave an official our tickets, but after a few minutes of him fondling the papers, he told me they were only good for the 11am flight. So for four hours we waited, observing a Swedish tour group munching on crackers and Lao women hoisting carry-ons of live chickens and eels in wicker baskets, slithering around like Jim Henson animatronic swamp creatures.

, at least 20 of them maintained since pre-colonial times. Every street, every alley seemed to possess an intangibly regal and old-world character. Older children bicycled to and fro while younger kids played tag along the side of the road. Street vendors sold soup and noodles to passing customers (probably their neighbors). Everything had a small town feel to it; people would smile and say "Sabai dee" to us when we walked by. It was early afternoon and the sun had just passed its peak - I'd guess it was about 90 degrees outside. But that didn't deter us as we strolled the boulevard along the Mekong for the first time. About 15 feet to our left, just off the edge of the street, the earth took a steep 100 foot drop down to the river valley floor. Along the beach families tended crops in small, neatly aligned vegetable gardens as boatman plied the shoreline in their motorized sampans.

, at least 20 of them maintained since pre-colonial times. Every street, every alley seemed to possess an intangibly regal and old-world character. Older children bicycled to and fro while younger kids played tag along the side of the road. Street vendors sold soup and noodles to passing customers (probably their neighbors). Everything had a small town feel to it; people would smile and say "Sabai dee" to us when we walked by. It was early afternoon and the sun had just passed its peak - I'd guess it was about 90 degrees outside. But that didn't deter us as we strolled the boulevard along the Mekong for the first time. About 15 feet to our left, just off the edge of the street, the earth took a steep 100 foot drop down to the river valley floor. Along the beach families tended crops in small, neatly aligned vegetable gardens as boatman plied the shoreline in their motorized sampans.

As we continued past Wat Nong Sikhonmeuang I noticed a group of kids playing in the open doorway of a house. I quietly approached them, trying to get a candid photograph. But one of the boys looked up at me and blew my cover, causing the girls to giggle and scurry behind the door, peeking their heads out from behind the teak wood frame as if to tease me and my camera. I playfully charged them, holding my camera to my face. Again they laughed and let out a giggling scream, running behind a wooden pole. The boys taunted the girls for not being brave enough to mug for the camera; eventually, some of the girls relented. An older man, perhaps one of their grandfathers, stood inside a garage just across the street, smoking his pipe and laughing while gesturing at the kids to pose for a picture. I got a few decent shots and thanked the kids: "Khop Jai, lai lai," thank you very much. "Sabai dee," they shouted back. I figured we had stumbled onto an unusually gregarious bunch of Lao children, but as we walked the streets of Luang Prabang Susanne and I concluded that outgoingness and joie de vivre was par for the course for the people of this lovely town. I could tell I was going to fall in love with this place.

As we continued past Wat Nong Sikhonmeuang I noticed a group of kids playing in the open doorway of a house. I quietly approached them, trying to get a candid photograph. But one of the boys looked up at me and blew my cover, causing the girls to giggle and scurry behind the door, peeking their heads out from behind the teak wood frame as if to tease me and my camera. I playfully charged them, holding my camera to my face. Again they laughed and let out a giggling scream, running behind a wooden pole. The boys taunted the girls for not being brave enough to mug for the camera; eventually, some of the girls relented. An older man, perhaps one of their grandfathers, stood inside a garage just across the street, smoking his pipe and laughing while gesturing at the kids to pose for a picture. I got a few decent shots and thanked the kids: "Khop Jai, lai lai," thank you very much. "Sabai dee," they shouted back. I figured we had stumbled onto an unusually gregarious bunch of Lao children, but as we walked the streets of Luang Prabang Susanne and I concluded that outgoingness and joie de vivre was par for the course for the people of this lovely town. I could tell I was going to fall in love with this place.