Sunday, November 10:

Sunday, November 10:We got up to the sound of street traffic around 9:30am. I felt I had had a good night's sleep, but Susanne argued otherwise - apparently I had awoken in the night, completely startled and confused, and then began to talk about the FBI in my sleep. She guessed that it had something to do with watching "The Rock" during the flight. I surmised it was some kind of X-Files thing.

Susanne didn't have much of an appetite yet, but I insisted on getting something to nosh on, so we stopped at Nirula's sweet shop. I got a "cheese biscuit," which I soon discovered was a biscuit of cheese-flavored dough and hot chilis. Not exactly what I was used to for breakfast. We walked around Connaught Circus to the Indian tourist bureau, where a nice Punjabi man gave us suggestions for purchasing train tickets to Agra and Varanasi, as well as what reasonable taxi fares around Delhi should be. He also confirmed a rumour I had read somewhere on the Net - the Taj Mahal was closed on Mondays for renovations. This now meant we'd have to go to Agra on Tuesday with our backpacks, store them somewhere, and then catch an overnight train to Varanasi. I wasn't looking forward to figuring out the logistics for that.

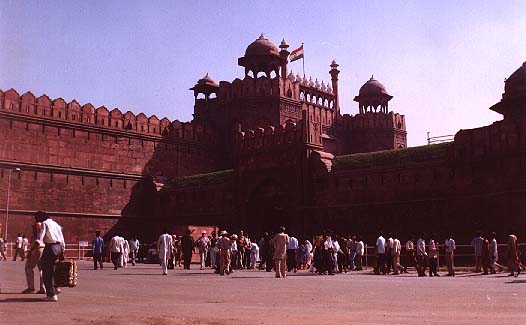

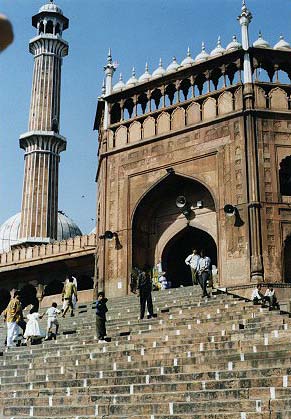

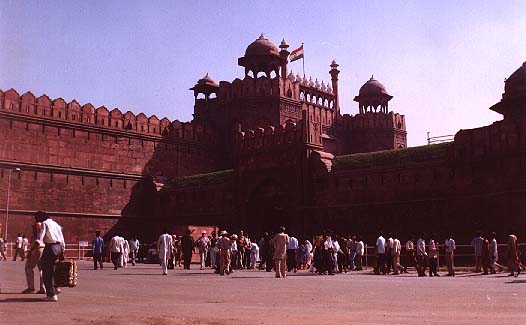

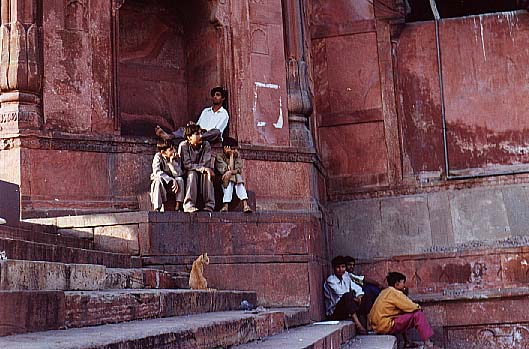

We left the tourist office and had a couple of delicious masala dosas for brunch at the Kovil restaurant. From Connaught Circus, we hailed an autorickshaw and headed north to Old Delhi to visit the city's Jama Masjid ("Friday Mosque"), the enormous 17th century Mosque of Shah Jehan, the Mughal emperor best known for building the Taj Mahal. Our timing was quite poor, though - noon prayers had just begun, and the mosque would be closed for the next hour. We decided to hike down and across the crowded streets of Old Delhi, through the maidan (Delhi's equivalent of a Central Park) to Lal Qila, the Red Fort. The fort is an immense red Agra sandstone complex built by Shah Jehan just before 1650. It took us 20 minutes just to walk alongside the fort's western wall and moat to reach the main entrance. While Susanne stopped to tie her shoes, we were accosted by two women in saris who pinned flags of India on our shirts and demanded a donation for their "school." Just to get them to go away, I handed them two rupees, about six cents, to which they responded by saying "Americans must pay paper money," which I ignored as we walked towards the ticket office.

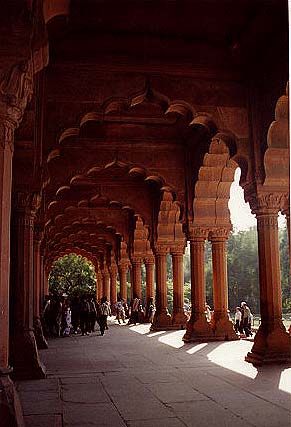

I was beginning to wonder when this would get interesting, but finally we found ourselves exiting the structure and entering an elongated grassy courtyard, at the end of which was the Diwan-I-Am, the emperor's hall of public audiences. In its prime, the Diwan and the Naqqar Khana were connected by an ornate covered hall, but the centuries had taken their toll and at that was left was the walkway and the greenery which graced both sides of it. We admired the Mughal architecture of the Diwan, a hypostyle hall nine bays wide and three bays deep. The emperor would use the hall as the place where citizens of the empire could come to redress for grievances and settle disputes. The Mughals prided themselves on their sense of justice, so they would always maintain a Diwan-I-Am at each of their palaces. Eventually, we made our way round to the back of it, where we found acres of grass and gardens, dotted by several white sandstone complexes. The gardens were in the Persian-influenced charbagh style - square grids of grass bisected by marble irrigation channels. It was a peaceful and relatively quite place to relax, so we lounged in the grass for awhile to take in the scenery. As we sat there, we noticed the echo of a feedback-riddled PA system that was emanating from a large circus tent on the northeast corner of the maidan. The effect of the sounds floating over the green pastures of the Fort and its gardens was quite surreal, but yet seemed totally normal for Delhi - a city of so many contradictions and oddities.

I was beginning to wonder when this would get interesting, but finally we found ourselves exiting the structure and entering an elongated grassy courtyard, at the end of which was the Diwan-I-Am, the emperor's hall of public audiences. In its prime, the Diwan and the Naqqar Khana were connected by an ornate covered hall, but the centuries had taken their toll and at that was left was the walkway and the greenery which graced both sides of it. We admired the Mughal architecture of the Diwan, a hypostyle hall nine bays wide and three bays deep. The emperor would use the hall as the place where citizens of the empire could come to redress for grievances and settle disputes. The Mughals prided themselves on their sense of justice, so they would always maintain a Diwan-I-Am at each of their palaces. Eventually, we made our way round to the back of it, where we found acres of grass and gardens, dotted by several white sandstone complexes. The gardens were in the Persian-influenced charbagh style - square grids of grass bisected by marble irrigation channels. It was a peaceful and relatively quite place to relax, so we lounged in the grass for awhile to take in the scenery. As we sat there, we noticed the echo of a feedback-riddled PA system that was emanating from a large circus tent on the northeast corner of the maidan. The effect of the sounds floating over the green pastures of the Fort and its gardens was quite surreal, but yet seemed totally normal for Delhi - a city of so many contradictions and oddities.

Susanne and I spent about 45 minutes wandering from hall to hall in the gardens. At the far end of the fort was the Diwan-I-Khas, the hall of private audiences, where Shah Jehan would sit on his legendary Peacock Throne- that is, until it was hustled away to Tehran by invading Persians in the 18th century. As its name would suggest, the Diwan-I-Khas was where the emperor would meet privately with his ministers and members of his court. The interior of the Diwan was covered with complex pietra dura inlaid engravings of bejeweled flowers. And along the edges of the walls read the famous Mughal exclamation:

"If there be a paradise on earth, it is here, it is here, it is here."A paradise it must have been, but even today it is an insular one, for just behind the Diwan and beyond the moat we could see an enormous open-air bazaar crowded with thousands of Delhi-wallahs. We could tell from our view next to the throne platform that this bazaar wasn't the type hoarded by throngs of tourists; instead, it was a true-to-life south Asian flea market where everything from carpets to camels could be hocked for the right amount of rupees.

After a brief visit to a dark and dank museum of Mughal art, we paused for a couple of cokes at a refreshment stand. We relaxed for about 20 minutes, which was time well spent for people-watching. The vast majority of visitors going by were Indian tourists, apart from the occasional westerner, who could easily be spotted with a copy of the Lonely Planet guide in hand and that damn paper Indian flag pinned to their chests (as an aside, I should probably point out here that Sus and I had earlier removed our flags, for we concluded they were the equivalent of us wearing badges that announced to Delhi's many touts, "We are tourists, please take advantage of us.")

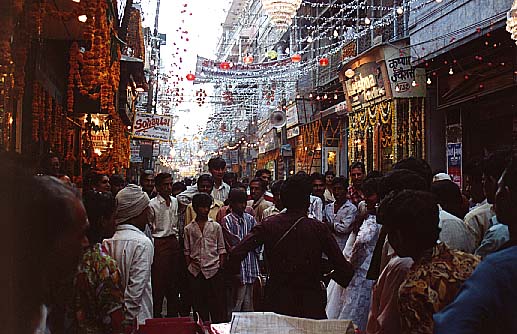

We headed out of the Red Fort and crossed the road to Chandni Chowk, the largest bazaar in Old Delhi. The Chowk ran east-west for about a mile, with dozens of tributary bazaars radiating down its many alleyways. In Shah Jehan's day, Chandni Chowk was the central commercial thoroughfare of Shahjehanabad, the vast capital city he built after abandoning his other great capital, Agra. Today it is still just as alive with activity, hopelessly congested with buyers, hawkers, and gawkers, though it appeared that most of the items being sold were day-to-day things like shoes, mops, even TV sets. Susanne and I had planned to work our way west and then southeast back to the Jama Masjid, but first we took a side trip down one of the many alleyways extending south of the Chowk. The alley was alive with people preparing for tonight's Diwali festivities, lighting candles, stringing garlands of orange carnations onto strings. A woman began to sing and dance as a man drummed a tabla. A crowd soon formed. It seemed like such a timeless moment, reminiscent of the winding alleyways of Cairo's Khan-al-Khalili or some other eastern market.

We headed out of the Red Fort and crossed the road to Chandni Chowk, the largest bazaar in Old Delhi. The Chowk ran east-west for about a mile, with dozens of tributary bazaars radiating down its many alleyways. In Shah Jehan's day, Chandni Chowk was the central commercial thoroughfare of Shahjehanabad, the vast capital city he built after abandoning his other great capital, Agra. Today it is still just as alive with activity, hopelessly congested with buyers, hawkers, and gawkers, though it appeared that most of the items being sold were day-to-day things like shoes, mops, even TV sets. Susanne and I had planned to work our way west and then southeast back to the Jama Masjid, but first we took a side trip down one of the many alleyways extending south of the Chowk. The alley was alive with people preparing for tonight's Diwali festivities, lighting candles, stringing garlands of orange carnations onto strings. A woman began to sing and dance as a man drummed a tabla. A crowd soon formed. It seemed like such a timeless moment, reminiscent of the winding alleyways of Cairo's Khan-al-Khalili or some other eastern market.

As we returned to Chandni Chowk and hung a left towards the road to Jama Masjid, I started to develop what I soon realized was a caffeine withdrawal headache. It became worse with each rickshaw horn blast and with each cry of the chai-wallahs passing by - a tortuous cacophony that was devoid of any potential relief. After ten minutes or so of this, I noticed that my aches were affecting my concentration, and that we were becoming somewhat lost. I felt like we were heading in the right direction, but the distance we needed to travel was much further than I had imagined. Our solution to our dilemma literally ran over my foot - a bicycle rickshaw. We hopped on board, sitting on a thin rubber pad that clung precariously to the bicycle. As we rode along, I could tell that my concerns were justified, for the trip to Jama Masjid took 15 minutes, even by bike.

At the mosque, we climbed the steps once again and started to walk in when we were reminded to take off our shoes. As fate would have it, by the time we bared our feet, the muezzin called out to announce the beginning of late afternoon prayers. Once again, we had been beaten by the tenets of Islam. Before a mullah was able to tell us to leave, we got a brief look at the immense courtyard inside the mosque, which easily held over 25,000 people in prayer. If we had time, we'd try again tomorrow.

At the mosque, we climbed the steps once again and started to walk in when we were reminded to take off our shoes. As fate would have it, by the time we bared our feet, the muezzin called out to announce the beginning of late afternoon prayers. Once again, we had been beaten by the tenets of Islam. Before a mullah was able to tell us to leave, we got a brief look at the immense courtyard inside the mosque, which easily held over 25,000 people in prayer. If we had time, we'd try again tomorrow.

Now in an autorickshaw, we rode south into New Delhi and into Connaught Circus. With the passing of each kilometer, we could here more and more cherry bombs and firecrackers going off as the evening Diwali celebrations were warming up. Fireworks, candles and other incendiaries are an intregal part of Diwali, which in Sanskrit literally means 'a row of lights.' For Hindus, Diwali commemorates the mythical return home of Ramayana hero Rama with his wife, Sita. Rama had been long exiled in the forest by the trickery of his stepmother, Queen Kaikeyi - these were his wilderness years, or vanvaas. As a subplot during this exile, Sita was kidnapped by Ravana, the evil god-king of Lanka. After a fantastic battle, Ravana and his troops were destroyed - it was a pyrrhic victory for Rama. When he returned home with Sita to take their place as King and Queen of Ayodhya, the streets of the city were lined with candles and lamps - hence Diwali, a row of lights. Today, Diwali serves as a reminder of the event, as well as the beginning of the Hindu new year and a celebration of success and prosperity.

Back at the hotel, we decided to nap for a while and then head back out around 7pm to get some dinner. When the time came, our plan was to cross over Connaught Place to the southern side of the circus, where there was a string of cheap, yet well-recommended restaurants. Exiting the hotel, we were greeted with mouthful of sulphur as the smoke of dozens of firecrackers drifted down the street. Small explosions occurred all around us, but we didn't comprehend the extent of it until we reached the center ring of the circus. It was, in all honesty, like a war zone - continuous, indiscriminate concussions exploded in every direction. Very few fireworks could actually be seen in the sky; only the incessant thunder and the billowing clouds of smoke were present. It was like a big-city 4th of July celebration, yet without all the bombs bursting over a centralized point. It was festive anarchy.

All of Delhi, both Hindus and Muslims, were celebrating from the rooftops - and that turned out to be a small problem for us. After a full circle around Connaught, we couldn't find a single open restaurant. Apart from the occasional small crowd experimenting with a 50-foot string of cherry bombs, not a soul was in sights. We did, however, manage to pick up a new friend in the form of a thin black dog that followed our every step for 20 minutes. It was eventually scared off by a poodle that started to bark at me as it was being walked by a large family.

Having completed the circuit round Connaught, we found ourselves back at Nirula's whose four restaurants were open (Nirula's, it turns out, is sort of a weird Indian hybrid of Howard Johnson's hotel/restaurant chains, but with better accommodations). The smoky cafe of their main restaurant was filled with upper-middle class Indians, enjoying late night beers and dosas. I ate a mixed tandoori platter, while Susanne attempted to enjoy what had to be the worst French onion soup ever made. Her meal was saved with a nice piece of naan and some curried dal that had come with my dinner.

As we sat there, eating our dinner and observing the restaurant's other patrons, we both had simultaneous flashbacks to two-in-the-morning munchy runs at the local Village Inn or IHOP back in high school. Except at this IHOP, the locals munched on samosas and Zen pancakes (regular old pancakes, but made out of lentil flour, I think). The West had arrived with a vengeance in India, and it was beginning to give me heartburn. Time for a couple of Pepto Bismols and a good night sleep.

Take me back to the journal index.

Take me back to Andy's Waste of Bandwidth.