Sunday, November 17:

Sunday, November 17:

Patan and Bhaktapur

I had a pretty poor night's sleep thanks to a serious of unpleasant coughing fits. But a large pot of tea, a couple of hard boiled eggs (whites only) and a pancake for breakfast helped make up for it. Before getting started with our trips to Patan and Bhaktapur (both former city-states and the two largest cities in the valley after Kathmandu), I returned once again to the email parlor in Thamel. I had been short a few rupees the night before, so I settled my bill and sent another brief message home. We then hopped an autorickshaw for the 20-minute ride to Patan, just south of Kathmandu. The roads were congested and the exhaust was thick, so we promised ourselves to switch to taxis for a while just to give our lungs a breather, so to speak.

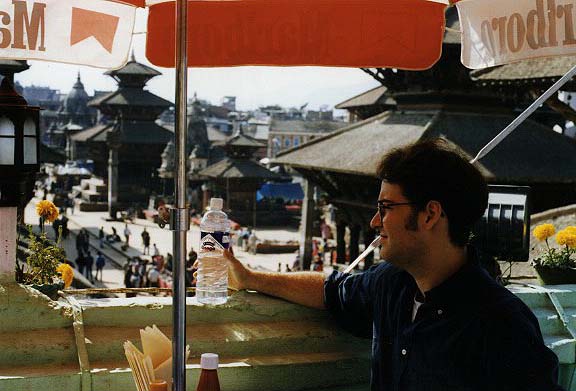

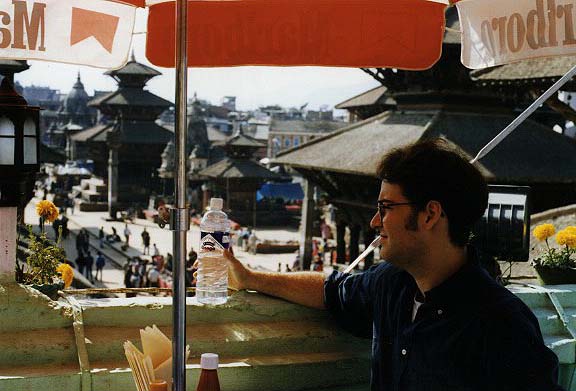

Patan's Durbar Square is similar to Kathmandu's, with its pagodas, shrines, and royal palace, all contained in a couple of acres. But the square itself was more spacious, thanks to a series of earthquakes that decimated numerous temples over the centuries. As tragic as these losses were, the eventual effect was to create a square that feels much less claustrophobic and crowded than Kathmandu Durbar Square. I can only imagine what Patan must have looked like before the tremors, even as recently as 1934, the time of the last major quake.  Neither Susanne nor I were feeling fully up to snuff this morning, so our stroll around the square was slow and tempered. Within an hour or so of exploring, we were in dire need of refreshment, so we climbed up to a restaurant terrace which afforded a splendid view of the square. It was perhaps one of the few spots one could actually capture much of Durbar Square in a single picture, so we took advantage of it, taking snapshots and enjoying the scenery.

Neither Susanne nor I were feeling fully up to snuff this morning, so our stroll around the square was slow and tempered. Within an hour or so of exploring, we were in dire need of refreshment, so we climbed up to a restaurant terrace which afforded a splendid view of the square. It was perhaps one of the few spots one could actually capture much of Durbar Square in a single picture, so we took advantage of it, taking snapshots and enjoying the scenery.

Three cups of tea later, I was ready to explore some more. Below the cafe were several art galleries that specialized in watercolors and thangkas, traditional Tibetan paintings of surreal Buddhist icons and mandalas. I was particularly taken in by one artist who worked in paint and ink to create thangkas with a modern twist - landscapes of Nepal dotted by dozens of small cartoon people, sort of like a Buddhist Where's Waldo poster. His pictures had a wonderfully touching feel to them, so I broke down and bought one for a little less than $30, signed by the artist. Well worth every penny, I thought.

We then spent a short amount of time at Patan's Golden Temple, just north of Durbar Square. It's hidden among modern buildings, which almost caused us to miss it completely. Yet inside the temple's courtyard we found gilded shrines surrounded by dozens of prayer wheels. It was quite a sight, but as is often the case, we had to keep a distance from the shrine itself, as the grounds of the inner courtyard were closed to non-Hindus (read: Westerners). Susanne and I then headed back to Durbar Square for one last look. It must have been early afternoon at this point, and I figured we had just enough time to get to the ancient city of Bhaktapur 10 kilometers east of us. Three or four hours there should be more than enough time for a nice walk around the city.

The cab ride to Bhaktapur was awful. Susanne nearly got carsick, so we had to sit outside the gates of the city just to be sure that everything was ok. Feeling a bit better, Susanne and I headed into Bhaktapur after paying the the whopping $5 entrance fee. The old city of Bhaktapur is completely sealed off from traffic, so it's one of the few large towns in Nepal that still maintains its mediaeval flavour. Through the gate, we were greeted by yet another Durbar Square. It is by far the most spacious of the Valley's three durbar squares, but not unlike Patan's square, this extra room was the unintended consequence of numerous earthquakes. I had read that many travelers consider Bhaktapur Durbar Square to be the best of the bunch, but by this point, I was feeling a little durbared out, kind of like the feeling you get after visiting one too many French cathedral or Egyptian mosque.

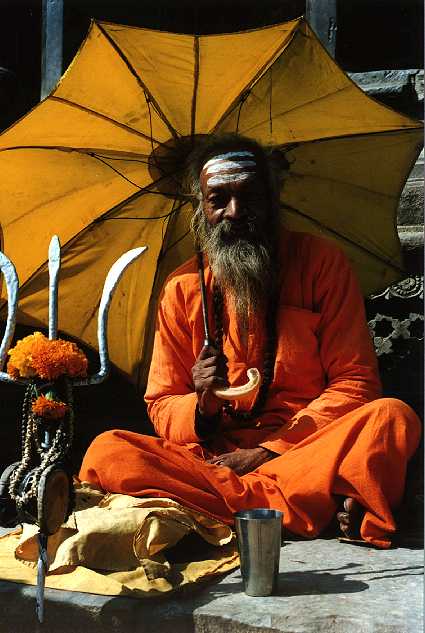

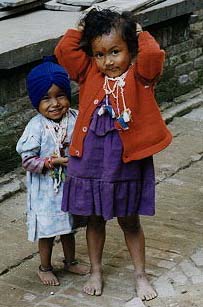

We decided to take a three hour walking tour of the inner bowls of Bhaktapur, following a well-tread route suggested by the LP guide. As soon as we began the walk, the presence of other westerners decreased abruptly. Now we were alone among the local Newari people as they went about their daily business - women sifting grain and drying out chilis in large piles; men hanging thousands of feet of freshly dyed wool; mothers nursing babies; old men giving pujas at the corner Ganesh shrine. We walked as slowly as possible trying to absorb every sight, sound and scent. At one point we climbed a hill to a small temple, where a woman sat and kept watch while talking with a young friend. We we explored the temple, I found a small pill of red tika powder by a lingam, so I put a splotch of it on Susanne's forehead. As we left the temple, the woman noticed Susanne's tika and began to laugh hysterically, giggling something in Newari. I took it as a sign of humorous approval. Susanne did not. She removed her tika.

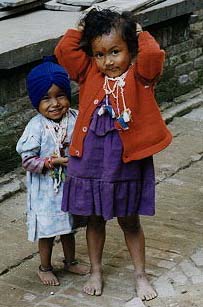

We climbed up another hill into a series of alleyways. Two women were weaving cloth while a boom box blasted some song that sounded distinctly like Motorhead. It was quite odd. As the music faded behind us we returned to a tranquil street setting, with more women sifting grain and drying chilis, while small children in blue school uniforms chased puppies and chickens around the square. (As an aside, the number of puppies in the Kathmandu Valley is astounding. Around every corner, more puppies. I'm convinced that Nepal must have more puppies per square foot than any other country.)

We climbed up another hill into a series of alleyways. Two women were weaving cloth while a boom box blasted some song that sounded distinctly like Motorhead. It was quite odd. As the music faded behind us we returned to a tranquil street setting, with more women sifting grain and drying chilis, while small children in blue school uniforms chased puppies and chickens around the square. (As an aside, the number of puppies in the Kathmandu Valley is astounding. Around every corner, more puppies. I'm convinced that Nepal must have more puppies per square foot than any other country.)

Around 2pm, we reached another square. There was a nice little restaurant with a good view, so we stopped for a light lunch of soup and buffalo milk yogurt - the local specialty. The restaurant had more than its fair share of Americans lounging about, and the amount of English being spoken made me feel claustrophobic. After lunch, we continued east and then south to a rural part of the city. The neighborhood appeared to be poorer than the previous ones we had seen in Bhaktapur, and there were significantly less people around. Clouds appeared overhead, shifting us into a somewhat somber mood. We pushed forward and crossed a river by some small ghats and a Ganesh shrine. Three children were playing on a tree swing above the ghats, so I took a picture with a high shutter speed to see if I could capture one of the kids as the swing reached upward:

We cut back over the river and made a feeble attempt at not getting lost. At one point, we couldn't decide whether to hang a left or a right in order to return to Durbar Square. Susanne said left, I said right. We tried left for a bit, then backtracked and went right. Suddenly, we were back at the small square we had just eaten an hour earlier. We should have gone left. At least now I was able to get my bearings on the map, and in about ten minutes, we were back where we started, among the pagodas and shrines of the square.

I hailed a cabby to take us back to Thamel. He wanted 350 rupees to take us back - seven dollars. I bargained down to 200 rupees, and we got in the car. We didn't get far, though, because the streets ahead of us became blocked by a procession of small children with red costumes and big sticks. Our driver said it would be a few minutes before we could get the taxi through the crowded street, so we got out and watched the parade. It was a Newari stick dance. Lined up in two parallel rows, the children would march and dance in unison, and then engage in ritual combat with their sticks, fencing with the kid in the row across from them. Behind the children, a crowd of cheerful adults played instruments and sang, while teenagers weaved in and out of the procession in large papier mache masks. Susanne and I had a field day with our cameras as the children fought with their sticks and parents smiled proudly at their youngsters' skills.

As the procession moved on, we hit the road again and made it back to Thamel in about 20 minutes. There was still a bit of sunlight left in the day, so I again opted for tea on the roof. A German woman came up top and said guten tag to me, to which I responded with a polite "tag." She then started to talk away in German until I was able to convey to her that I couldn't understand a word she said. Susanne and I wrote on the roof while waiting for dinner - I had ordered Gacok, a traditional Tibetan stew which takes several hours to steam, so we waited patiently and worked up an appetite. It was well worth the wait. The gacok was by far the best meal of the trip and in general, one of the most satisfying dinners I've ever had. The gacok was served in a metal steamer shaped like a goblet with a donut-shaped mold at the top. In the mold were cellophane noodles, meatballs, chicken, buffalo, vegetables, tofu, prawns, and other random Asian delicacies. Below the mold was a self-contained wood stove that had been smoldering for hours. In the center of the mold was a round hole full of boiling water, so when the mold was covered with a lid, the top of the food would steam while the bottom of the food was heated directly by the burning embers. The gacok was also served with fried rice, momos and noodles. An enormous feast for ten dollars. More expensive than any other meal on the trip, but worth every rupee.

As the procession moved on, we hit the road again and made it back to Thamel in about 20 minutes. There was still a bit of sunlight left in the day, so I again opted for tea on the roof. A German woman came up top and said guten tag to me, to which I responded with a polite "tag." She then started to talk away in German until I was able to convey to her that I couldn't understand a word she said. Susanne and I wrote on the roof while waiting for dinner - I had ordered Gacok, a traditional Tibetan stew which takes several hours to steam, so we waited patiently and worked up an appetite. It was well worth the wait. The gacok was by far the best meal of the trip and in general, one of the most satisfying dinners I've ever had. The gacok was served in a metal steamer shaped like a goblet with a donut-shaped mold at the top. In the mold were cellophane noodles, meatballs, chicken, buffalo, vegetables, tofu, prawns, and other random Asian delicacies. Below the mold was a self-contained wood stove that had been smoldering for hours. In the center of the mold was a round hole full of boiling water, so when the mold was covered with a lid, the top of the food would steam while the bottom of the food was heated directly by the burning embers. The gacok was also served with fried rice, momos and noodles. An enormous feast for ten dollars. More expensive than any other meal on the trip, but worth every rupee.

Good food leads to a solid night's sleep. Tomorrow's plan: the sacred ghats of Pashupatinath and the great stupa of Bodnath.

Next Entry: Pashupatinath and Bodnath

Take me back to the journal index.

Take me back to Andy's Waste of Bandwidth.

EdWeb: Exploring Technology and School Reform, by Andy Carvin. All rights reserved.

Neither Susanne nor I were feeling fully up to snuff this morning, so our stroll around the square was slow and tempered. Within an hour or so of exploring, we were in dire need of refreshment, so we climbed up to a restaurant terrace which afforded a splendid view of the square. It was perhaps one of the few spots one could actually capture much of Durbar Square in a single picture, so we took advantage of it, taking snapshots and enjoying the scenery.

Neither Susanne nor I were feeling fully up to snuff this morning, so our stroll around the square was slow and tempered. Within an hour or so of exploring, we were in dire need of refreshment, so we climbed up to a restaurant terrace which afforded a splendid view of the square. It was perhaps one of the few spots one could actually capture much of Durbar Square in a single picture, so we took advantage of it, taking snapshots and enjoying the scenery.  Sunday, November 17:

Sunday, November 17: We climbed up another hill into a series of alleyways. Two women were weaving cloth while a boom box blasted some song that sounded distinctly like Motorhead. It was quite odd. As the music faded behind us we returned to a tranquil street setting, with more women sifting grain and drying chilis, while small children in blue school uniforms chased puppies and chickens around the square. (As an aside, the number of puppies in the Kathmandu Valley is astounding. Around every corner, more puppies. I'm convinced that Nepal must have more puppies per square foot than any other country.)

We climbed up another hill into a series of alleyways. Two women were weaving cloth while a boom box blasted some song that sounded distinctly like Motorhead. It was quite odd. As the music faded behind us we returned to a tranquil street setting, with more women sifting grain and drying chilis, while small children in blue school uniforms chased puppies and chickens around the square. (As an aside, the number of puppies in the Kathmandu Valley is astounding. Around every corner, more puppies. I'm convinced that Nepal must have more puppies per square foot than any other country.)

As the procession moved on, we hit the road again and made it back to Thamel in about 20 minutes. There was still a bit of sunlight left in the day, so I again opted for tea on the roof. A German woman came up top and said guten tag to me, to which I responded with a polite "tag." She then started to talk away in German until I was able to convey to her that I couldn't understand a word she said. Susanne and I wrote on the roof while waiting for dinner - I had ordered Gacok, a traditional Tibetan stew which takes several hours to steam, so we waited patiently and worked up an appetite. It was well worth the wait. The gacok was by far the best meal of the trip and in general, one of the most satisfying dinners I've ever had. The gacok was served in a metal steamer shaped like a goblet with a donut-shaped mold at the top. In the mold were cellophane noodles, meatballs, chicken, buffalo, vegetables, tofu, prawns, and other random Asian delicacies. Below the mold was a self-contained wood stove that had been smoldering for hours. In the center of the mold was a round hole full of boiling water, so when the mold was covered with a lid, the top of the food would steam while the bottom of the food was heated directly by the burning embers. The gacok was also served with fried rice, momos and noodles. An enormous feast for ten dollars. More expensive than any other meal on the trip, but worth every rupee.

As the procession moved on, we hit the road again and made it back to Thamel in about 20 minutes. There was still a bit of sunlight left in the day, so I again opted for tea on the roof. A German woman came up top and said guten tag to me, to which I responded with a polite "tag." She then started to talk away in German until I was able to convey to her that I couldn't understand a word she said. Susanne and I wrote on the roof while waiting for dinner - I had ordered Gacok, a traditional Tibetan stew which takes several hours to steam, so we waited patiently and worked up an appetite. It was well worth the wait. The gacok was by far the best meal of the trip and in general, one of the most satisfying dinners I've ever had. The gacok was served in a metal steamer shaped like a goblet with a donut-shaped mold at the top. In the mold were cellophane noodles, meatballs, chicken, buffalo, vegetables, tofu, prawns, and other random Asian delicacies. Below the mold was a self-contained wood stove that had been smoldering for hours. In the center of the mold was a round hole full of boiling water, so when the mold was covered with a lid, the top of the food would steam while the bottom of the food was heated directly by the burning embers. The gacok was also served with fried rice, momos and noodles. An enormous feast for ten dollars. More expensive than any other meal on the trip, but worth every rupee.