Thursday, November 20

Hilltribe Trek

Our first trek. We had been longing to go on a walking expedition ever since visiting Nepal last year. We had set aside three days for hillwalking through Nepali villages but Susanne got a bad stomach bug, so we spent the time in the proximity of Kathmandu instead. Our trek would have to wait for Northern Thailand. Most trekkers walk over a three to five day period, which sounds really nice in theory, but in practice I have a feeling we'd get bored or exhausted before it was over. So today we'd compromise with a full day trek: about four hours of walking interspersed with stops at five hilltribe villages.

Most of the local hilltribes (also known as Montagnards in former French Indochina colonies) migrated here from Yunnan province in China or the steppes of Tibet in the last several hundred years. Those tribes from Tibet (Lisu, Karen, etc.) speak Tibeto-Burman languages while those from Yunnan (Hmong, Yao, etc.) speak Tai languages, for the Thai and Lao peoples also originated in the area around southern Yunnan and northern Vietnam. Unlike the Thai, Lao and Shan Burmese peoples, though, the hilltribes have never fully adapted into the modern world. They rarely recognize national borders, speak distinct languages and have different social mores, including polygamy. Some might draw a parallel between the hilltribes and the Roma (gypsies) of Eastern Europe - nomads of a foreign past, fiercely proud of their heritage, poorly integrated into society.

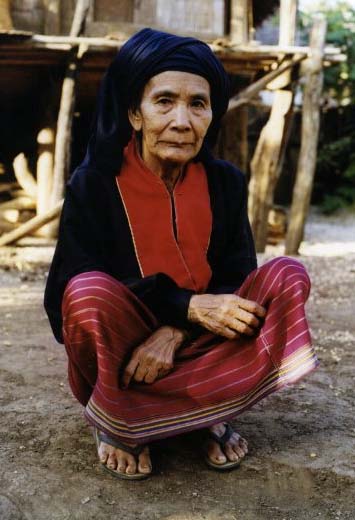

|

| Palong villager |

In Thailand, sadly, hilltribes are not granted status as Thai citizens. They cannot go to Thai schools and must pay for their own basic education, which many cannot afford. Their systemic lack of education keeps Thailand's montagnards at the bottom of the education scale, causing their economic and social status to suffer accordingly. Yet the hilltribes survive, maintaining their ancient cultures on subsistence agriculture and craftmaking. Over the last 20 years, the outside world's fascination with the hilltribes' "primitive" customs has created a cottage industry of treks and tours, where westerners visit the tribes to meet the community members, take pictures and buy souvenirs. It's a double-edged sword - treks give tribes a source of hard currency revenue yet expose them to the habits of western culture, from television to drug addiction. And in some cases, the tribes learn to rely on trekking revenue to the point of abandoning traditional sources of income. What will happen when the trekking fad dies down? It's hard to say. I find myself somewhere in the middle of the argument. I hate to see cultures threatened, yet I too wish to take part in this ethnic voyeurism, visiting tribes and taking pictures before returning to the comfort of my hotel. The only folks who seem like the real winners are the trek operators, who reel in the cash all over northern Thailand - certainly more cash than any of the tribes could ever get without them.

Today though I'd put my doubts aside and enjoy the trip. I didn't want to judge the experience before I began it. At 8:30 in the morning a songthaew picked us up at the hotel. We were the first two trekkers in a group of seven, a rather modest-sized group. It would be at least an hour before we had assembled the entire group, but after a brief stop at the trekking agency we headed out of Chiang Mai for the two hour drive to Phrae. Joining us on the trek were Ann and Raymond, a Hong Kong couple living in New York; Mary and Peter, a recently retired pair of English doctors; and Moreno, a prematurely greying Italian, always quiet yet always with a mysterious smirk on his face. Leading our group was Sam, a 30-year-old Lisu raised and educated by American missionaries. His English was good and his knowledge of Lisu an other hilltribe languages made him an appropriate guide for our short journey.

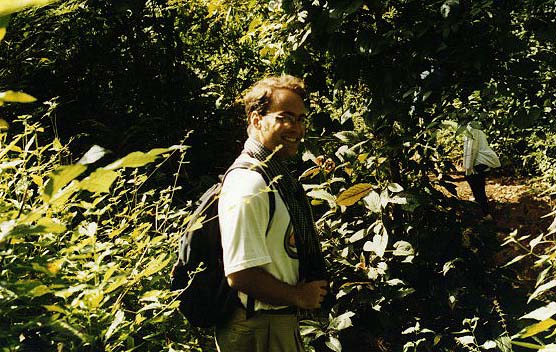

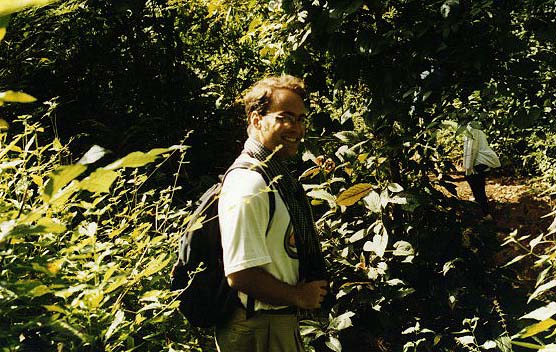

|

| Andy walks the Thai forest |

The songthaew dropped us at the end of a paved road. We were supposed to take the Nissan pickup truck another two kilometers along a dirt path to the first village, but recent rains had made much of the path unnavigable by vehicle. So for half an hour we walked through the mud to reach the official starting point of the trek, a small Lahu village. The dirt road had the consistency of hard, wet clay - not much traction and a bit rough on the feet. But we managed just fine with Sam leading the group over the rolling dirt path. Sam was very talkative, always asking us questions about what we did for a living, how long we were traveling, and so forth. He made a point of using your name whenever he addressed you: "So Andy, have you ever gone on a trek before?" "And Susanne, what do you do in America?" I could tell he wanted to cover as many topics as possible, undoubtedly to practice his English vocabulary, but at times I felt like I was being interviewed for a job. "Were you here for the monsoon?" "Are you glad you came to Thailand, with the recent drop in the Thai baht?" At least it passed the time well. And I actually got to remember the names of the people in a group, all because of Sam's incessant questioning.

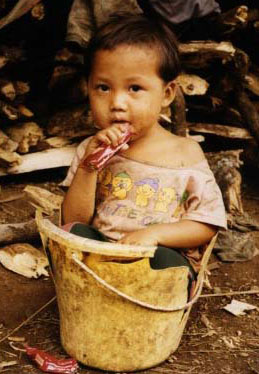

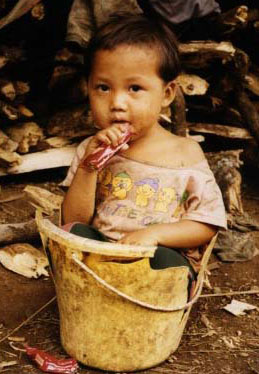

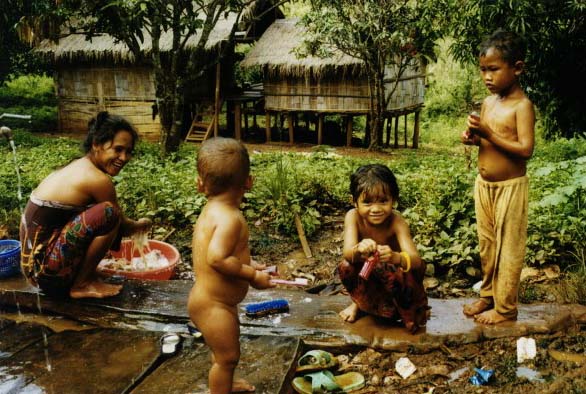

The dense damp forest opened up as we curved around the side of a steep hill. We could see a valley just ahead, its upper edges decorated with crops of soy, corn and what appeared from a distance to be marijuana. Smoke rose from the bottom of the valley - the Lahu village must be straight ahead. Five or six thatched roof stilt houses encircled a large vertical water tank, the only water source for this poor farming village that lacked plumbing and electricity. A Lahu woman, naked from the waist up, washed her children under a flowing water pump. When she noticed our arrival she politely yet quickly raised the cloth of her skirt to cover her chest, as if she didn't want to shock or embarrass us. Sam passed out chocolate bars to the women in our group. "Give them to the children. They don't see Westerners very often so they might get scared. They'll accept chocolate from women, but not men." I asked Sam whether it was expected of us to give the children a couple of baht for taking their pictures. "No. Absolutely not. It will spoil them. A child who gets money for nothing but their smile will then expect everything for nothing. They will all become thieves." Fine, I thought, we'll then destroy their teeth with chocolate instead. Susanne and Mary approached two of the older children, perhaps six or seven years old, and offered them chocolate, which they accepted rather shyly but stuffed their faces once they got the wrappers open. I wondered if every one of our pictures would feature chocolate-smeared kids with wrappers stuck in their chubby little hands.

An older woman sat on the porch of one of the stilt houses, a young child nestled between her legs and a large pile of yellow corn cobs next to her. She sat on the porch, observing us as we observed the rest of the village. I made eye contact with her and smiled; she didn't smile back, though she nodded her head in polite acknowledgment, allowing me to take her picture. What did she think of all of this, this group of farangs in heavy leather hiking boots, with their little cameras snapping off in every direction? I became very self-aware at this moment, causing me to once again question our right to be there in the first place. Before I could dwell on it for long, though, Sam called out to me - lunch was being served in a small gazebo just above the village. We all had fried rice (I was stuck with pork fried rice, for the chicken had run out sooner than expected) and a bowl of bananas and fresh pineapple. I always feared eating fruit on these trips of ours, but peeled fruit is fairly safe, so I relished each bite of the decadently sweet pineapple and the small, tart bananas that grew all over Southeast Asia. Sam was tossing a small round fruit in the air, one that I hadn't seen before. I asked him what it was and he said, "This is a mangosteen," and proceeded to cut it open to reveal a small citrus-like fruit at its center. He popped the fruit out and let me taste it - tangy, somewhere between a green apple and a tangerine. Wish we had more than the one he was carrying.

An older woman sat on the porch of one of the stilt houses, a young child nestled between her legs and a large pile of yellow corn cobs next to her. She sat on the porch, observing us as we observed the rest of the village. I made eye contact with her and smiled; she didn't smile back, though she nodded her head in polite acknowledgment, allowing me to take her picture. What did she think of all of this, this group of farangs in heavy leather hiking boots, with their little cameras snapping off in every direction? I became very self-aware at this moment, causing me to once again question our right to be there in the first place. Before I could dwell on it for long, though, Sam called out to me - lunch was being served in a small gazebo just above the village. We all had fried rice (I was stuck with pork fried rice, for the chicken had run out sooner than expected) and a bowl of bananas and fresh pineapple. I always feared eating fruit on these trips of ours, but peeled fruit is fairly safe, so I relished each bite of the decadently sweet pineapple and the small, tart bananas that grew all over Southeast Asia. Sam was tossing a small round fruit in the air, one that I hadn't seen before. I asked him what it was and he said, "This is a mangosteen," and proceeded to cut it open to reveal a small citrus-like fruit at its center. He popped the fruit out and let me taste it - tangy, somewhere between a green apple and a tangerine. Wish we had more than the one he was carrying.

As soon as we had finished eating we packed up our trash and began the two hour hike to a White Karen village. We climbed out of the valley along the slope of a hill dotted with corn stalks, rice, wheat and papaya trees. Sam pointed out some bright red wild ginger growing just off to the left of the path, behind which stood a large marijuana plant. I asked him if the Lahu planted marijuana as a crop. "Sometimes, yes," he said, "but if they didn't it would still grow everywhere. It's a weed, you know." The hill leveled off for about 100 yards but then climbed steeply through a bamboo covered path. The shade of the bamboo was small comfort compared to our huffing and puffing from the height of the ascent. Still, Sam ventured well ahead of the group, never pausing to catch his breath. It bothered me that he was always surging 50 feet in front of the rest of us - clearly we were novices at this stuff and I could sense some frustration among the group as we climbed further up. Some of us would catch up for a time but would soon fall back and be replaced by someone else. This was also problematic for Sam would often point out plants and crops to those who could keep up with him, but the rest of the group, much further behind, wouldn't hear a thing. Several times I made a point to say to him, "Could you repeat that back here?" and after awhile he got better at addressing us as a group.

For well over two hours we marched through rolling hill country, up and down, up and down. I began to hate the uphill climb - I was sweaty enough just going along the flatland - but as I acclimated to the pace I decided that downhill was actually worse, its steep drops and wet clay causing a swift and uncertain descent. Our investment in heavy-tread hiking boots paid off greatly during these stretches, though I still had to save myself from a few close-call slides down some nasty rocks. Poor Mary and Peter - they were shlepping full-size backpacks, and as retirees, they were much older than the rest of us, yet they often set the pace with Sam up front. Man, they made me feel out of shape; I bet they loved every minute of it, watching all of us young folks huffing and puffing. Either way, it was more pressure to keep up.

Despite my exhaustion, the forest was beautiful - dense and lush, the wetness from the week's rains accent its jungle qualities. Sometimes between the thicket of trees you could see granite cliffs in the distance - I pictured undisturbed hilltribe villages settled below them, tending their crops with the sounds of cattle bells echoing off the rock face. Would any of the villages look like this? The Lahu village was so poor, almost needy - could any village look otherwise now? Perhaps I would find out.

We paused for a five-minute water break at the edge of yet another hill. Susanne and I had run out of water at this point - no problem, since Sam carried four extra bottles for the group. As he finished his own bottle, Sam threw it beyond the path into the woods. Jesus! Of all people, I figured that Sam, as a professional guide, a group leader and as a local villager, would make a concerted effort to encourage eco-friendly trekking. Instead the path was his garbage dump. The bottle was far out of my reach, though if it had been, I wondered how he would have reacted if I angrily picked up his trash. I guess there wasn't much I could do except set a better example and carry my rubbish for the length of the trip. I shook out our empty bottle, crushed it and put it in my backpack.

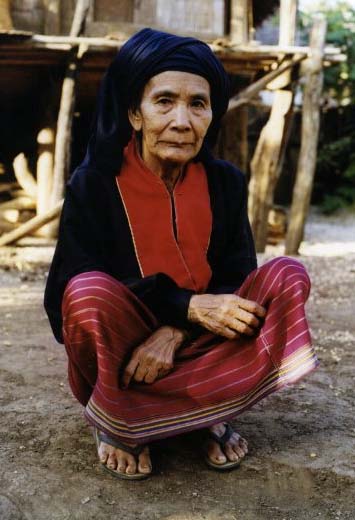

|

| White Karen villager |

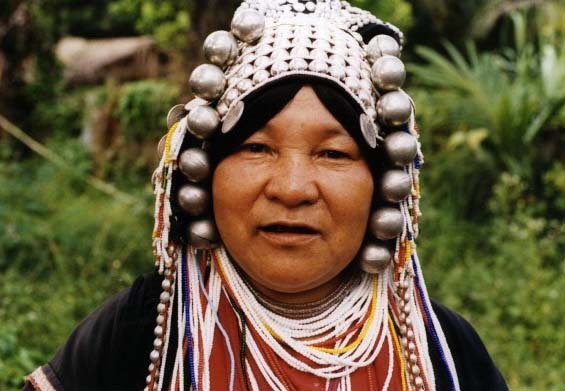

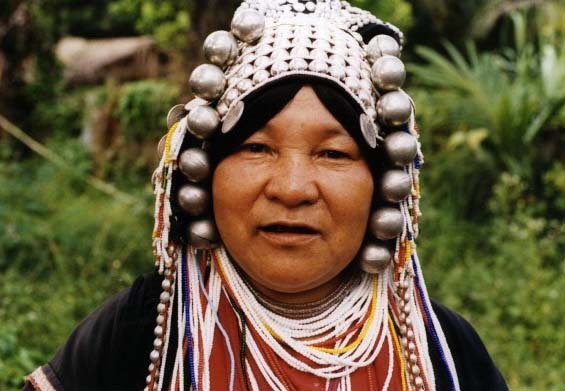

"How much further to the next village?" someone asked. "Thirty minutes," Sam said, the same answer he'd given us for the last hour. We all laughed, but inwardly I thought that a few people were starting to get annoyed with him. This time, though, he wasn't far off the mark, for half an hour later the hills leveled off as we reached a series of rice paddies below a sheer cliff. Two water buffalo stood by a stream, tied to wooden fences. Perhaps this was the village I had envisioned after all. The settlement, populated by White Karen tribespeople from Burma, was significantly larger than the Lahu village and appeared to be wealthier as well, with sturdy stilt houses and a white stone school house topped by a satellite dish. A group of children, some young women and an older man sat under a tree, weaving baskets out of palm fronds and straw. They smiled as we approached and nodded with approval when we motioned to our cameras. Ann and Mary handed our more chocolates to another group of kids. Yes, my premonition of every child smeared with chocolate was fated to be true. Five or six stout women in full tribal headgear followed us around, shoving trinkets in our faces. "Buy this, good silver, look pretty," they said as I politely declined. But I was admittedly confused, for their costumes suggested they were Akha and Lisu, not White Karen. What were they doing here? "They're all my relatives," Sam laughed. I guess they had come down the road from their village to corner us before anyone else got the chance.

|

| Akha woman in traditional costume |

|

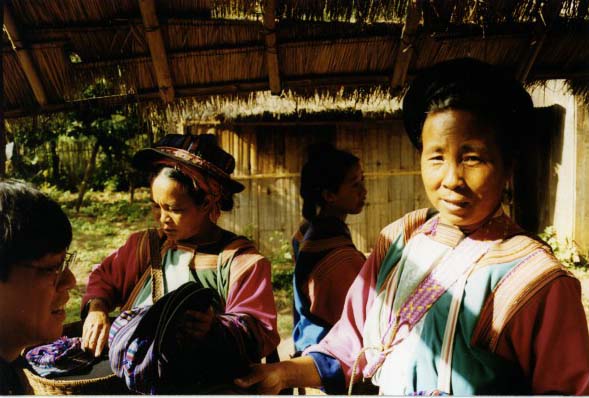

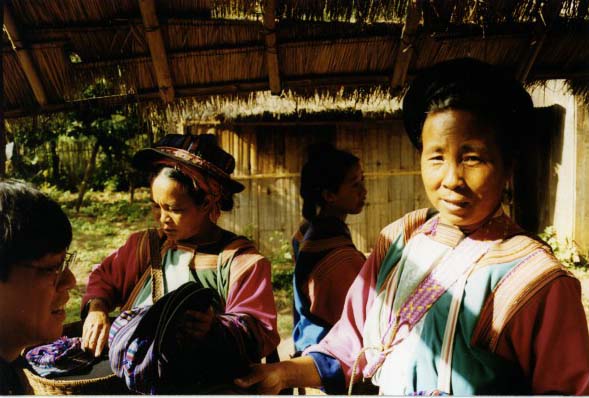

| Lisu women selling handicrafts |

The Karen tribespeople, though, attempted no sales pitches. There were daily chores to be done and we were more like strangers passing through rather than potential customers. The Lisu and Akha women followed us around the village. Raymond noticed some of them had black teeth and he asked one of them in Cantonese to open their mouths - she understood him and smiled broadly. Raymond was the director of East-West medicine at New York's Cornell Medical Center so he was very interested in tribal medical practices. The other women pointed to pouches full of white powder and green leaves - betel nut was the culprit. People all over Asia from India to Taiwan chew betel nut for its intense buzz. Unfortunately habitual betel chewing causes teeth to blacken and rot, and can eventually cause mouth cancer. A younger Lisu woman smiled and showed off her perfect pearly white teeth. "Do you chew betel nut?" Raymond asked. She laughed and shook her head no. One of the older women gave her a little push on the shoulder, smiling and laughing, her teeth black as coal.

|

| Lisu child sitting in a bucket |

We spent another ten minutes with the Karen villagers and their Lisu and Akha neighbors before regrouping for the brief 15 minute walk up to the next village. Down the path, Lisu and Akha lived next to each other and it was difficult to tell where one village ended and the other began. There were more children around here - school was out for the afternoon. These children seemed much more accustomed to having westerners around, for they would wave and say hello to us, sometimes over and over. Some of them, though, walked around with their hands out, aggressively demanding "Thai baht" as the toll for passing through their village, picture or no picture. Sam said something to them in Lisu and they grimaced and moaned something back to him in Lisu - "you adults are all alike" seemed to be the general tone of it. An older woman egged them on, waving her hand at us, saying "Pay baht, pay baht," but a younger woman near her laughed and motioned her hands as if to tell us to ignore her. Clearly this village had seen visitors with loose change before and the damage was done, at least until they got the message enough times from Sam and other Lisu villagers who lament the slippery slope of alms begging.

At the far end of the Lisu village I could see the Nissan songthaew that had brought us from Chiang Mai. We'd need to drive to the last village, which was too far away to visit on foot. First, though, an older Lisu man brought out two large bunches of tiny, dark skinned bananas, each no more than four or five inches long. They had just ripened and had a pleasant tart taste, rather different from their larger western cousins. We ate them enthusiastically; the old Lisu looked pleased. I asked Sam if we should pay something for the fruit. "You are his guest. Do not even offer or you may insult him. Eat more." So I smiled at the man, grabbing another banana while saying in Thai, "Aroi mahk mahk," - very tasty. "Aroi mahk," he said back, laughing in approval. I just wish I knew how to say it in Lisu as well.

|

| Lisu woman weaving traditional cloth |

On the other side of the dirt road I noticed a small church with a cross on top. American missionaries successfully converted several Lisu tribes before World War II and some of them, including this one, practiced a blend of Christianity and Tibeto-Burman animism. The missionaries also gave the Lisu their first written language, about 60 years ago. On the front of the church I saw strange writing; it was Latin script, though many of the letters were upside down or backwards: "VISU 7ADER U30NG." I asked Sam why the missionaries had chosen to invert the letters. "So it will look like our own language," he said. The French had forced the Vietnamese to Latinize their script and attempted to do the same in Cambodia as well. It wasn't a very popular move. Perhaps the missionaries concluded that changing the letters to be different from how westerners used them would be a fair compromise: a whole new script, though oddly familiar and dyslexic. I also imagined it would be easier to fit printing presses with this new script, since there was no need to design new type faces - flipping them upside down our reversing them would do the job. Personally I was interested in discussing this further, but the rest of the group was all too happy occupying their mouths with more bananas.

|

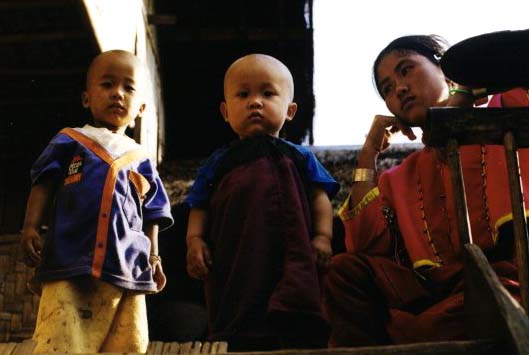

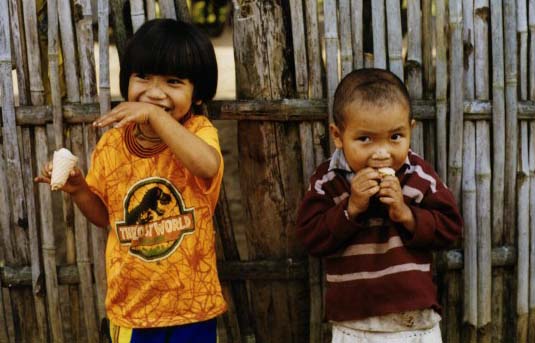

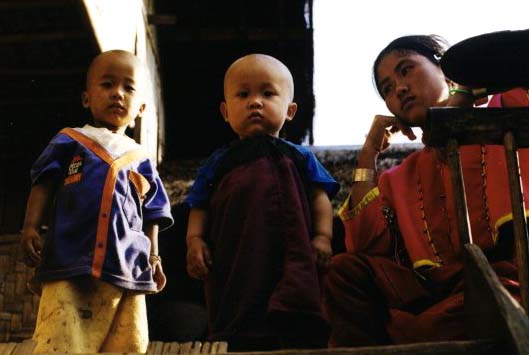

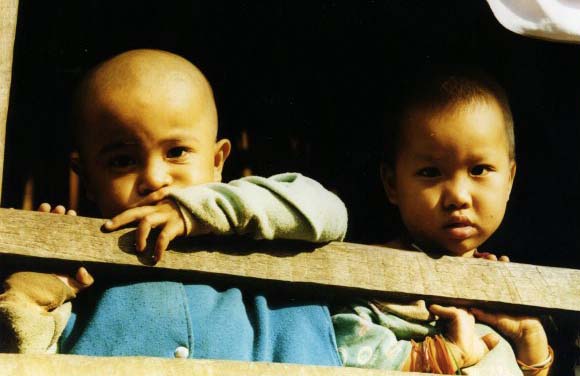

| Palong children standing in a stilt house |

We piled back into the truck and drove for about 20 minutes down some very rough unpaved roads to our last stop, a Palong village. Not much is known about these recent immigrants to Thailand, except they are from Burma and speak a Mon language, which means they are distantly related to the Khmers of Cambodia. The women of the village wore black costumes highlighted with bright red and blue. The outfits looked familiar, but I was in no position to guess where (or whether) I'd seen them previously. I didn't see any men here - women were taking care of the children, working in the fields, pumping water from the wells. A young Palong woman sat with four boys, ages two to 10 perhaps, the youngest of which seemed quite fascinated by us. Another woman and her son pounded rice using a wooden hammer attached to a long lever, six or seven feet long. The woman stood over the far end of the lever, pressing all of her weight on her right foot. As she started, her foot pressed down the lever, raising the hammer over the rice. When she shifted her weight to her other foot, the hammer fell hard on the rice, breaking the bran from the white meat of the rice. She repeated the process at a regular, yet casual pace, hammering every four seconds or so. I had tried to press one of these rice hammers back in the Karen village and found it difficult to raise and lower the mallet with any control - each time the hammer crashed down and Sam would cringe, fearing I'd break the wooden bowl below. I couldn't imagine doing this for hours at a time.

On a small tree behind one of the houses I saw a large, gourd-like fruit, about 18 inches across and ten inches wide. Some kind of melon tree?, I wondered. "Jackfruit," Sam said as he approached me and the tree. "It's kind of like a durian except it doesn't smell or taste like rotten onion." I had heard many stories about the durian, the smelliest fruit on earth, but hadn't seen one yet. I'm pretty sure they're out of season. I suppose if I'm really desperate I could find one in a Chinese market back in the States. Until then, I'd have to imagine just how awful it would taste.

|

| Young Palong woman |

Not far from the truck Susanne and I took pictures of several cute children who seemed to enjoy the attention. Another young Palong woman - I couldn't tell if she was their mother or older sister - smiled and encouraged the youngest child to say "hello" and "bye bye."

|

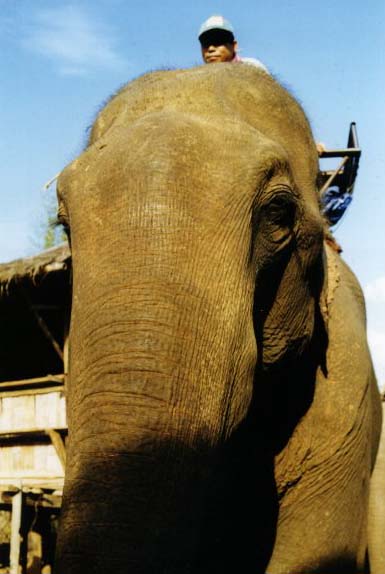

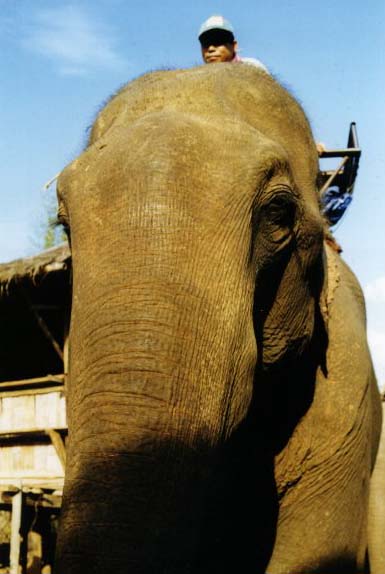

| Close encounter with an elephant |

Then from down the street I could see an elephant lumbering towards us with two westerners on top of it. There were at least two other elephants behind it. "Here's your elephant parade," I said to Susanne. As the first elephant approached us it took interest in a tall papaya tree growing next to the roadside. The elephant started to rip off some of its leaves and eat them. They must have been yummy, for the elephant proceeded to rip the entire tree out of the ground, breaking off the trunk down at the roots. It brought the enormous log to its mouth and bit down, shattering the wood into numerous pieces with a loud, piercing crunch. The mahout that was guiding the elephant whacked its ear - "Bad girl! Bad girl!" - while the German couple atop its back looked shocked and embarrassed. Those of us on the roadside laughed hysterically and watched with significant awe as the beast literally ate the tree trunk, leaving 50-pound chunks as scraps. The elephants who was next in line each noshed on the leftovers, repeatedly shattering the remains of the log into smaller and smaller pieces. The Germans on Elephant #3, perhaps too far back to witness the initial pachydermal carnage, looked down at the leaves, branches and wood below them. "Oh... Papaya," one of them said, causing even more hysterics among those of us watching from below. We gave them a wide berth as they passed, not wanting to be dessert for any of these magnificent beasts.

The sun was getting low in the sky so we returned to the truck for the 90 minute ride back to Chiang Mai. Mary and Peter stayed behind - they'd spend the night at the Palong village and trek one more day. The seemed eager for more walking. More power to them. The rest of us seemed eager to sit in the songthaew with the cool wind blowing by as we drove back to town. I noticed many of the locals burning piles of trash in front of their houses along the way. Though Chiang Mai had good public sanitation and waste removal, out here in the country burning your trash insured faster disposal than waiting for someone to pick it up for you. It also contributed to Thailand's notorious pollution. At least things aren't as bad here as they are in Indonesia.

Another dinner at Pizza Hut. I know there's something of a wasted opportunity in our choice of pizza again, but I rationalized it by noting how long and hard a day it had been for us. Pizza was great recovery food and I was too tired to deal with another plate of grisly chicken bone at some awful Thai restaurant. Besides, in Chiang Mai, practically every restaurant is American, Italian, Chinese, Mexican - anything but Thai food - so it's a chore in itself finding good Thai food. I couldn't decide how I felt about the trek, though - I suppose I enjoyed the experience. Yes, I did enjoy it. The whole affair wasn't the exploitative invasion of hilltribe privacy as I had feared. Yet I am still uncomfortable with our visits today. We were prying eyes, watching families go about their daily business, trying to capture "quaint" and "exotic" native moments. I know I'll be debating this in my head for a long while. I wonder if my opinions will change when I get the pictures developed; if they come out well, obviously I'll be pleased, but I worry that good photos will make me feel all the more guilty about intruding. Perhaps it would be best if I leave it at that for now and wait and see.

After wrapping up our Italian-American feast we crossed the road into the Chiang Mai night market. No rain tonight, so none of the vendors were scurrying around to cover their goods. Too bad - it was kind of funny, in a cruel sort of way. Tonight it was dry, so the market overflowed with tourists shopping for souvenirs and other junk. The bazaar atmosphere was entertaining for a while but it had been a long, long day. I was so happy to take off my shoes that night.

An older woman sat on the porch of one of the stilt houses, a young child nestled between her legs and a large pile of yellow corn cobs next to her. She sat on the porch, observing us as we observed the rest of the village. I made eye contact with her and smiled; she didn't smile back, though she nodded her head in polite acknowledgment, allowing me to take her picture. What did she think of all of this, this group of farangs in heavy leather hiking boots, with their little cameras snapping off in every direction? I became very self-aware at this moment, causing me to once again question our right to be there in the first place. Before I could dwell on it for long, though, Sam called out to me - lunch was being served in a small gazebo just above the village. We all had fried rice (I was stuck with pork fried rice, for the chicken had run out sooner than expected) and a bowl of bananas and fresh pineapple. I always feared eating fruit on these trips of ours, but peeled fruit is fairly safe, so I relished each bite of the decadently sweet pineapple and the small, tart bananas that grew all over Southeast Asia. Sam was tossing a small round fruit in the air, one that I hadn't seen before. I asked him what it was and he said, "This is a mangosteen," and proceeded to cut it open to reveal a small citrus-like fruit at its center. He popped the fruit out and let me taste it - tangy, somewhere between a green apple and a tangerine. Wish we had more than the one he was carrying.

An older woman sat on the porch of one of the stilt houses, a young child nestled between her legs and a large pile of yellow corn cobs next to her. She sat on the porch, observing us as we observed the rest of the village. I made eye contact with her and smiled; she didn't smile back, though she nodded her head in polite acknowledgment, allowing me to take her picture. What did she think of all of this, this group of farangs in heavy leather hiking boots, with their little cameras snapping off in every direction? I became very self-aware at this moment, causing me to once again question our right to be there in the first place. Before I could dwell on it for long, though, Sam called out to me - lunch was being served in a small gazebo just above the village. We all had fried rice (I was stuck with pork fried rice, for the chicken had run out sooner than expected) and a bowl of bananas and fresh pineapple. I always feared eating fruit on these trips of ours, but peeled fruit is fairly safe, so I relished each bite of the decadently sweet pineapple and the small, tart bananas that grew all over Southeast Asia. Sam was tossing a small round fruit in the air, one that I hadn't seen before. I asked him what it was and he said, "This is a mangosteen," and proceeded to cut it open to reveal a small citrus-like fruit at its center. He popped the fruit out and let me taste it - tangy, somewhere between a green apple and a tangerine. Wish we had more than the one he was carrying.