|

| Opium poppy in Hmong village garden |

Friday through Sunday,

November 21-23

Doi Suthep and the Hmong Village "Poppy Field";

Wasting Away in Chiang Mai;

Bangkok Transit Stop

We had another day and a half to kill in Chiang Mai and we planned to spend most of that time relaxing at cafes, doing absolutely nothing at all. We were quite successful much of the time but we did manage to spend a few hours visiting Doi Suthep, a mountain to the west of town. Doi Suthep is best known for a large wat that sits on its eastern slopes. It's one of the holiest shrines in northern Thailand, attracting large crowds for both the temple and the view of Chiang Mai from the top of the mountain.

that sits on its eastern slopes. It's one of the holiest shrines in northern Thailand, attracting large crowds for both the temple and the view of Chiang Mai from the top of the mountain.

A few steps outside of our guesthouse we hired a cheery songthaew driver to take us for the 45-minute trip up the mountain and back. As we reached the outskirts of Chiang Mai the road climbed slowly into a series of hairpin turns. Our driver was in no rush; we ambled all the way. Though Doi Suthep is only 1676 meters high the number of winding turns stretches the actual drive uphill to over six miles from the base of the mountain. A continuous stream of touring buses and minivans passed us in both directions. I guess it'd be a bit crowded up top. Our driver dropped us near the steps leading to the temple and told us to meet him down the street when we were ready to go back to Chiang Mai. I asked him if we could also go to a Hmong village on the far side of the mountain but he said no, for he wasn't allowed to drive past the Doi Suthep temple checkpoint. We'd have to hire a second taxi - only a handful of them were allowed to proceed. "Nothing I can do," he said. " It's mafia. Taxi mafia. They control who goes where." Wonderful. I guess we'd worry about visiting the Hmong village later.

driver to take us for the 45-minute trip up the mountain and back. As we reached the outskirts of Chiang Mai the road climbed slowly into a series of hairpin turns. Our driver was in no rush; we ambled all the way. Though Doi Suthep is only 1676 meters high the number of winding turns stretches the actual drive uphill to over six miles from the base of the mountain. A continuous stream of touring buses and minivans passed us in both directions. I guess it'd be a bit crowded up top. Our driver dropped us near the steps leading to the temple and told us to meet him down the street when we were ready to go back to Chiang Mai. I asked him if we could also go to a Hmong village on the far side of the mountain but he said no, for he wasn't allowed to drive past the Doi Suthep temple checkpoint. We'd have to hire a second taxi - only a handful of them were allowed to proceed. "Nothing I can do," he said. " It's mafia. Taxi mafia. They control who goes where." Wonderful. I guess we'd worry about visiting the Hmong village later.

|

| Doi Suthep temple |

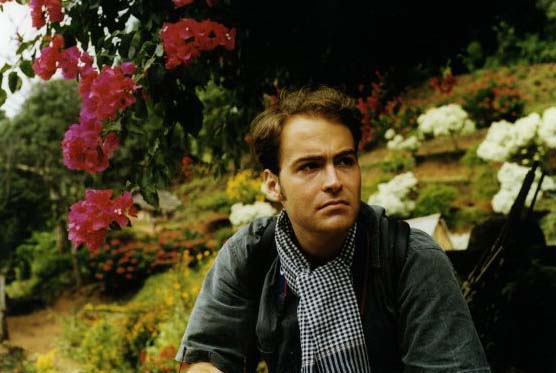

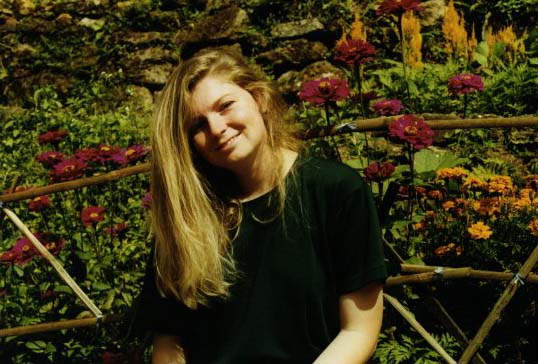

The marble steps of Doi Suthep teemed with tour groups, school children and devout pilgrims - certainly more people than we had seen at any other site in Thailand, save the Royal Palace in Bangkok. We walked up the steps, marveling at the glimmering stone and mirrored tile serpents that slithered down each side of the steps. Susanne tried to get a picture of me near the top of the steps, but a continuous stream of tourists kept getting in the way of the shot. At the summit we reached a large marble platform with a golden temple at its center. I had a brief flashback to the Swayumbunath stupa in Kathmandu - the long climb, the incense, the crowds - yet here I didn't feel that same sense of mystic awe I had felt in Nepal. Doi Suthep, as beautiful a temple it is, is also one large souvenir shop; the Coke signs and enormous amounts of tourist paraphernalia detracted from the supposed sacrality of the temple. Fortunately, inside the temple itself you could get away from the crass capitalism, so as long as you retreat within this marble and gold sanctuary there is fleeting peace. Many visitors lit candles and incense at shrines in the four corners of the temple. A frisky little kitten mounted surprise attacks on peoples' socks as they walked by - I occupied its attention for several minutes by dangling my camera strap above it, which it playful stalked with feverish abandon.

Outside the main temple crowds admired the view of Chiang Mai. Susanne and I paused for a moment and looked. No temples, no rolling hill country - only urban sprawl and distant billboards for Johnny Walker and Pizza Hut. Chiang Mai from above, Chiang Mai from below, it all felt so disappointingly familiar.

We took a brief tram ride down to the bottom of the temple steps, where we hired another songthaew to take us around to the Hmong village and back for 200 baht. We were getting ripped off for sure, but apart from a five mile walk in each direction, this was the only way we'd get to the other side of the mountain. The air was chilly as we drove further up Doi Suthep. We descended after a reaching the summit, winding slowly to the western slope and eventually to the Hmong village, which occupied a prime spot in a valley 4000 feet above Chiang Mai.

|

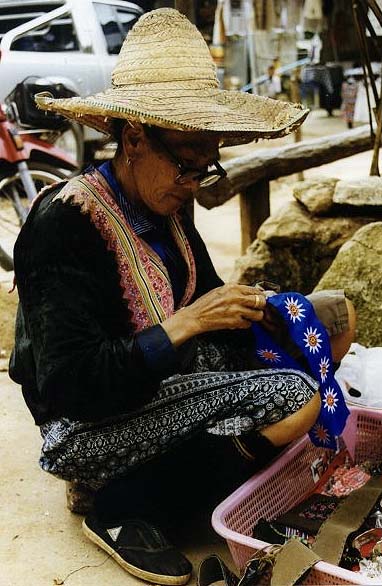

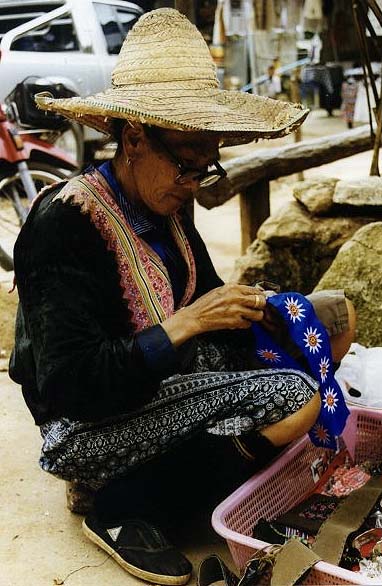

| Hmong woman, Doi Suthep |

I had no illusions about this particular village; there may have been a time when one would have found a pristine Hmong community, untouched by modernity, but now this small town was a thriving spot on the Chiang Mai tourist trail. The songthaew deposited us in front of the village in a large, unpaved parking lot full of motorbikes, minibuses and pickup trucks. I expected to see hordes of Western tourists inside, but there weren't too many people around; perhaps some of those trucks in the parking lot were owned by the Hmong themselves. The village itself occupied a series of rolling hills, with several small streets extending to a steep valley that served as the community's growing fields. It was a lazy afternoon market, with shops selling Hmong clothes, musical instruments, blankets and medicinal herbs as their keeps napped in the corner while listening to Thai pop music.

As we wound through the village I noticed a cardboard sign with the message "Hmong opium" and an arrow pointing to the left, back towards the hill-sloped gardens. Hmm. The Hmong, like other Thai hilltribes, are allowed by law to cultivate a small amount of opium poppies for their own use, but it was technically illegal to sell it to the outside world. What on earth could they be advertising here? We decided to investigate. A man sat under a shaded gate with a roll of ticket stubs and a small metal box. He pointed to a sign that said "ten baht entry," so we paid him the small sum to enter the gardens. We really had no idea if they were growing opium openly, but assuming they were, it made great sense to charge admission. I guess if you can't legally sell the stuff, you can make some money allowing westerners to gawk at it, growing out of the ground like any other weed. Whether or not these Hmong knew of the current heroin chic in America made no difference, I guess; as long as hippy trekkers came to town asking about poppy fields, why not make them pay 10 baht to see it? Besides, it's safer than allowing a bunch of stoners trek through the backcountry of the Golden Triangle, looking for it themselves. Burmese bandits or Karen rebels would probably blow them to kingdom come before they ever even saw their first poppy.

The fact that there were opium poppies to be found in this enormous garden made little difference to us, though, for the setting was lush and picturesque. A burst of colors, the valley was both a flower garden as well as a functional farm featuring fruit trees, corn, marijuana and soybeans. The fields sloped down the valley as a series of steps, with each earthen platform featuring a different combination of crops. We followed crescent-shaped footpaths through the gardens, winding back and forth along each tier. A large wooden waterwheel turned near the bottom of the gardens, spinning ever so slowly from the trickle of a mountain stream that cut through the heart of the valley. The tribe had their own little piece of paradise on the side of this mountain.

The air was thick with a syrupy sweet scent from the thousands of flowers blooming along the terraces. Yet we hadn't seen any poppy plants. We descended further into the garden until we reached the bottom, just above a tool shed. Here, I noticed three or four lonely long-stemmed flowers with bulbous heads and beautiful purple petals. Opium poppies. These delicate, humble blooms were the scourge of millions of addicts around the world. They just didn't seem to fit the job description very well. I took a couple of pictures of the flowers and managed to save a pair of petals pressed in my Lonely Planet book.

|

| Hmong carpet maker, Doi Suthep |

We eventually made our way out of the village to the other side of the mountain, where our ever smiling songthaew driving was waiting for us. Back at the hotel, we relaxed for the rest of the afternoon before spending our final evening at the Chiang Mai night market. On this particular evening I showed up with a particular goal in mind - I hadn't purchased any souvenirs in Thailand and was determined to find something acceptable in this vast bazaar. But as had been the case in previous visits here, I didn't see anything that struck my fancy; there was a lot of flea market junk, a lot of cheap clothing, but nothing that stood out and screamed "Thailand!" in my face.

Dejected, I suggested we return to the hotel. As we cut through the back of the market we stumbled upon an artist's cooperative made up of hilltribe families. I noticed a Lisu woman had several sets of placemats for sale, each embroidered in the tribe's distinct style of concentric oval loops. They appeared to be a great value but I didn't care for the colors she had available that night. When she said she didn't have any in green, a woman at an adjacent table said "Come here! Come here!" as her young daughter pulled out a huge cardboard box full of placemats of different colors. I quickly found four matching mats and negotiated a price of 125 baht, about three dollars, for the set. As I began to search for spare change, the woman who had displayed the first set of placemats came by with another set of four green mats. Apparently she had just found the set and now wanted me to buy from her instead of the little girl. The girl looked at me, wondering what I would do next. It seemed so petty to make them compete over a measly few bucks, so I apologized as politely as possible to the first woman and completed my transaction with the girl and her mother.

Elsewhere in the co-op, an Akha woman displayed a fine selection of wooden goods, including a four-stringed Thai banjo. It wasn't of professional quality - I'm sure there's no way the instrument would ever stay in tune - but it was the first item at the market to get my attention. I asked the woman how much she wanted for it and she said 700 baht. 17 dollars wasn't bad, but I'd have to lug this thing around for the rest of the week. I initially declined the offer, but she then began to pester me, saying "Very good, I need money, buy yes buy yes...." I started to think that if she just shut up for a minute I'd consider buying it. Eventually I said I'd take it for 200 baht. To my surprise, she then said 250 - six dollars. Having cut the price by two thirds, it suddenly seemed like a fine deal. The Akha woman wrapped it in several layers of newspaper, tying knots around its neck to hold the paper in place. It wasn't exactly a stellar packing job, but it would have to do for the moment. I now had my prize.

The next day was a total write-off as we waited for the 4pm overnight express train to take us back to Bangkok. Susanne and I bought postcards and hung out in a bakery by the eastern gate of the city. Before grabbing our bags at the hotel, we said goodbye to its two resident mascots, the old blind mastiff and his curly haired poodle mutt friend. They barely acknowledged us, for nap time was too precious in the heat of the afternoon. At the train station I purchased a bag of buns and a bottle of water. Hopefully this would be enough food to keep us full for the trip, since I had heard that Thai train food was expensive and dull. Unfortunately, because I couldn't read Thai I neglected to notice that I had purchased pork buns accidentally. I tried to eat one but the sight of the pork filling was enough to make me a vegetarian for life. We ended up ordering a mediocre meal of fried rice and pineapple slices for the bargain price of seven dollars. We should have slept on empty stomachs instead.

Back in Bangkok, we had another day to kill before heading out the next morning to Hong Kong. We checked into the Reno Hotel, a Vietnam War-era establishment that catered to low-end business travelers. It left much to be desired, but then again, so did Bangkok. I had really enjoyed my first day in Bangkok, with the temples, the palace, and especially the Thai boxing. But apart from these isolated highlights, Bangkok was a city without a soul. There was little for us to do apart from waste away a local shopping mall, where an ever growing mass of teenagers in designer jeans and sunglasses shopped for platform shoes. Our authentic Thai experience was not to be - at least not today - so we went hog wild with our western crassness, hanging out at the local Hard Rock Cafe before hitting a movie theatre for a showing of Air Force One. (The film, at least, had one unusual moment when the entire audience stood up in honor of the king while the theatre played a brief montage of royal photographs, all to the tune of the royal anthem which the king composed himself.) Watching Harrison Ford bash the hell out of Gary Oldman and his commie thugs gave us the craving for meat, so we ate at McDonalds before crashing at the Reno for the night. Apparently Bangkok had taken its toll on our sense of adventure.

that sits on its eastern slopes. It's one of the holiest shrines in northern Thailand, attracting large crowds for both the temple and the view of Chiang Mai from the top of the mountain.

that sits on its eastern slopes. It's one of the holiest shrines in northern Thailand, attracting large crowds for both the temple and the view of Chiang Mai from the top of the mountain.  driver to take us for the 45-minute trip up the mountain and back. As we reached the outskirts of Chiang Mai the road climbed slowly into a series of hairpin turns. Our driver was in no rush; we ambled all the way. Though Doi Suthep is only 1676 meters high the number of winding turns stretches the actual drive uphill to over six miles from the base of the mountain. A continuous stream of touring buses and minivans passed us in both directions. I guess it'd be a bit crowded up top. Our driver dropped us near the steps leading to the temple and told us to meet him down the street when we were ready to go back to Chiang Mai. I asked him if we could also go to a Hmong village on the far side of the mountain but he said no, for he wasn't allowed to drive past the Doi Suthep temple checkpoint. We'd have to hire a second taxi - only a handful of them were allowed to proceed. "Nothing I can do," he said. " It's mafia. Taxi mafia. They control who goes where." Wonderful. I guess we'd worry about visiting the Hmong village later.

driver to take us for the 45-minute trip up the mountain and back. As we reached the outskirts of Chiang Mai the road climbed slowly into a series of hairpin turns. Our driver was in no rush; we ambled all the way. Though Doi Suthep is only 1676 meters high the number of winding turns stretches the actual drive uphill to over six miles from the base of the mountain. A continuous stream of touring buses and minivans passed us in both directions. I guess it'd be a bit crowded up top. Our driver dropped us near the steps leading to the temple and told us to meet him down the street when we were ready to go back to Chiang Mai. I asked him if we could also go to a Hmong village on the far side of the mountain but he said no, for he wasn't allowed to drive past the Doi Suthep temple checkpoint. We'd have to hire a second taxi - only a handful of them were allowed to proceed. "Nothing I can do," he said. " It's mafia. Taxi mafia. They control who goes where." Wonderful. I guess we'd worry about visiting the Hmong village later.