Tuesday, November 19:

Tuesday, November 19:

A random walk in Kathmandu

Our alarm went off at 8am. I was feeling significantly better; unfortunately, Susanne appeared significantly worse. She wasn't able to keep down even the piece of dry toast she had for breakfast, while I successfully (and somewhat guiltily) scarfed down a full course meal. Because of Susanne's condition, it was pretty clear that she was in no shape to wander about just yet. So I agreed to head out on my own for a couple of hours and then check back in at 1pm to see how she was doing.

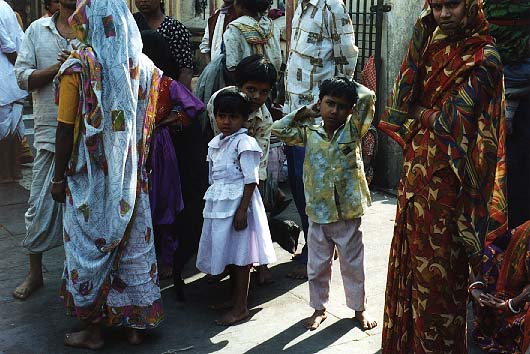

I spent a bit of time in Thamel browsing for potential souvenirs. Lots of ideas, but nothing stood out and screamed at me. I started to head south to Thahiti Tole, one of the many market squares between Thamel and Durbar Square, but instead of continuing down my usual route south to the palaces and pagodas, I hung a left and walked southeast into uncharted territory. The street and its alleyways were similar to the rest of Thamel - lots of trekking shops, t-shirt stalls, thankga galleries, and curious in every window. But after a couple of minutes of walking, the crass commerce died down and a more traditional Asian market atmosphere rolled in. Women sold huge bouquets of flowers (most of them real, of course, but I did spot a silk flower shop); stall after stall offered fine earthenware, brass and iron crockery. A man squatted under a thin doorway, hammering and polishing gold rings held on a wood rod between his feet. Small crowds gathered to watch two young teenagers playing a game of chess, cheering and passing money back and forth each time a player took one of his opponent's chess pieces, while just across the street, two old men played their own game, in full concentration and bothered by no one.

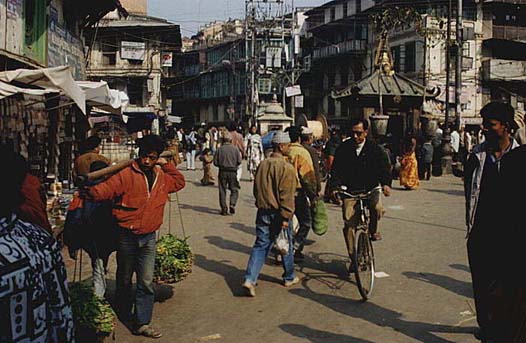

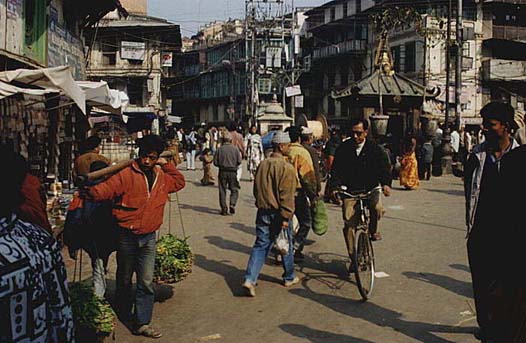

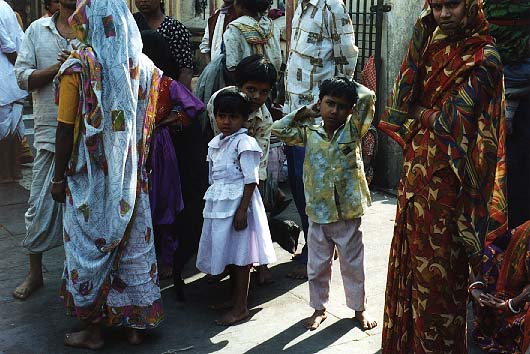

I slowly strolled the main road, talking it all in as I observed the crowds. The noise level increased steadily the deeper I went, until it peaked at a huge square and intersection. I had found Asan Tole, a major gathering place for commerce and religious ceremonies. Asan Tole is the crossroads for six major streets, always jammed with shoppers, merchants, and worshippers, no matter the time. Situated in the middle of the square was a temple to Annapurna, the goddess of prosperity and abundance. Whether Annapurna brought prosperity to Asan Tole, or Asan Tole brought in Annapurna to celebrate its prosperity, who's to say. There were also two other temples, both very small. I didn't recognize the god in one of them, but the other shrine's elephant-headed deity gave it away instantly as a Ganesh temple.

I slowly strolled the main road, talking it all in as I observed the crowds. The noise level increased steadily the deeper I went, until it peaked at a huge square and intersection. I had found Asan Tole, a major gathering place for commerce and religious ceremonies. Asan Tole is the crossroads for six major streets, always jammed with shoppers, merchants, and worshippers, no matter the time. Situated in the middle of the square was a temple to Annapurna, the goddess of prosperity and abundance. Whether Annapurna brought prosperity to Asan Tole, or Asan Tole brought in Annapurna to celebrate its prosperity, who's to say. There were also two other temples, both very small. I didn't recognize the god in one of them, but the other shrine's elephant-headed deity gave it away instantly as a Ganesh temple.

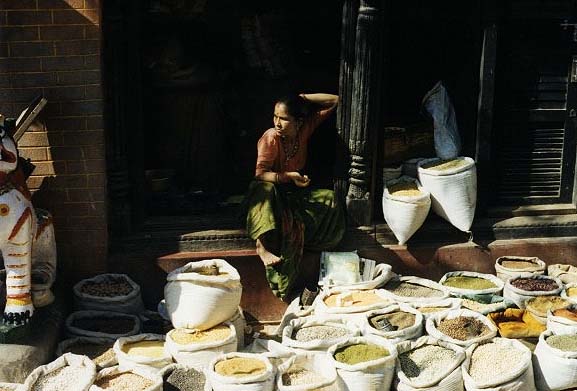

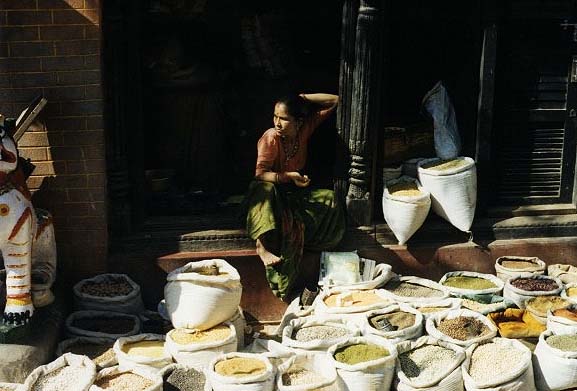

I stood awhile by a massive spice shop, inhaling the fumes of the essential oils as men used mortars and pestles to grind cumin, tamarind seeds, anise and coriander. Somehow I managed to get into a brief argument with a bicycle rickshaw-wallah who insisted that I had no business walking around on such a nice when I could instead be enjoying his services as my chauffeur for the day. Once he had moved on, I took advantage of the hustle and bustle of the square and took numerous pictures of people going about their business. Vegetable vendors were the easiest target, and only one of them asked for baksheesh in return.

I stood awhile by a massive spice shop, inhaling the fumes of the essential oils as men used mortars and pestles to grind cumin, tamarind seeds, anise and coriander. Somehow I managed to get into a brief argument with a bicycle rickshaw-wallah who insisted that I had no business walking around on such a nice when I could instead be enjoying his services as my chauffeur for the day. Once he had moved on, I took advantage of the hustle and bustle of the square and took numerous pictures of people going about their business. Vegetable vendors were the easiest target, and only one of them asked for baksheesh in return.

From Asan Tole I headed southwest to Kel Tole, a much smaller square that bustled with activity, despite its size. As I continued, I noticed a gate and a passageway to my right which appeared to lead to some kind of courtyard shrine. I walked in and there in front of me was a magnificently ornate, two-tiered pagoda, guarded by statues on pedestals and a collection of smaller chaitya shrines. A group of eight men were sitting in a semicircle among the pillars and shrines. They were performing a puja of some sort, throwing rice into a wood and charcoal fire. The men were sporting what appeared to be armor-like vests and crowns that distinctly looked like Burger King paper crowns. To the left, three women in saris chatted away while filling several hundred small pottery cups with rice and drops of tika powder. And just behind them, a huge flock of pigeons swooped and swarmed as local devotees through offerings of corn in their direction, which the pigeons would dive for with every handful.

From Asan Tole I headed southwest to Kel Tole, a much smaller square that bustled with activity, despite its size. As I continued, I noticed a gate and a passageway to my right which appeared to lead to some kind of courtyard shrine. I walked in and there in front of me was a magnificently ornate, two-tiered pagoda, guarded by statues on pedestals and a collection of smaller chaitya shrines. A group of eight men were sitting in a semicircle among the pillars and shrines. They were performing a puja of some sort, throwing rice into a wood and charcoal fire. The men were sporting what appeared to be armor-like vests and crowns that distinctly looked like Burger King paper crowns. To the left, three women in saris chatted away while filling several hundred small pottery cups with rice and drops of tika powder. And just behind them, a huge flock of pigeons swooped and swarmed as local devotees through offerings of corn in their direction, which the pigeons would dive for with every handful.

Where on earth was I? I hadn't read about this place in the LP. I pulled it out as I sat by the pigeons, whose collective wing flapping emanated a surprisingly strong draft. I flipped through LP's walking tours of Kathmandu and eventually found a map that seemed to coincide with the route I had just taken from Asan Tole. Aha - there on the map I saw a marking for a shrine. I was at the Sweta Machhendranath Temple, a shrine dating back to at least the 16th century, revered by both Buddhists and Hindus, who interpret the statue of a Buddha-like figure on the main pillar as Buddha himself or an incarnation of Shiva, depending on who you ask. I spent a good deal of time at this temple, walking around the shrines and observing the ongoing rituals. I was the only westerner around, and no one seemed to mind my presence. I was even encouraged to take pictures by some of the people there.

Eventually, though, I backtracked to Kel Tole and hung a left toward Kilgal Tole, a rather dull plaza that served as the entry point to a square that supposedly had several points of interest. I entered a large white courtyard, the Yitum Bahal. Compared to the rest of the neighborhoods adjacent to it, Yitum Bahal was deserted. At the far end of the square was a small stupa, on which three young kids were playing. Behind it, a woman sifted grain into large circles. Just to the right of the stupa, I found the entrance to Kichandra Bahal, a small, but ancient courtyard dating back to the early 14th century. There was a minor pagoda inside it, and on the right was a kindergarten where I could see several dozen kids playing and singing with their teachers. Just above the school were brass plaques of the demon Guru Mapa, including a rather hilarious frieze of Mapa eating a small child, literally seizing the kid's head by his teeth, while a rather surprised-looking mother stood by, helpless. I can only imagine if the teachers at the kindergarten take advantage of this 600-year-old image for reinforcing discipline among the students.

From Yitum Bahal, I took a couple of shortcuts to reach Durbar Square. I had planned to relax for a while here, but I felt some rather unusual rumblings in my stomach, so I figured I'd better high-tail it over to a restaurant with a bathroom, just in case disaster struck. There were no places to go on Durbar Square itself, so at the southern end, I headed east across Basantapur Square, with its flea market assembly of souvenir sellers, and then cut south on Jochne, more commonly referred to as Freak Street. In the 60s, Freak Street was the place for hippies to hang out, listen to western music, and smoke unimaginable amounts of hash. Nowadays it's a quiet neighborhood, with most westerners having adopted Thamel as their new place of choice for food and shelter (minus the hash shops, courtesy of a 15-year-old crackdown by the government). There are still a few old restaurants and guesthouses here, so I went into the Kumari Cafe to find that bathroom I thought I needed so desperately. But by the time I got there, the pains had subsided, so I sat down in the cafe for another pot of black tea. At first, the restaurant played classical Indian music, which was what attracted me into the place from outside. But just as my tea arrived, they changed the radio station and began to blast bad Nepalese pop music. For the first time in Kathmandu, I didn't finish my entire pot of tea. The music made me do it.

It was now around 1pm, so I returned to Jyatha at a brisk pace to check on Susanne at the hotel, stopping only for another roll of film and a few more pictures around Asan Tole (the lighting was irresistible). Back at the hotel, Susanne looked like hell. She tried to get dressed for lunch, but gave up and told me to leave and get lunch on my own. I ended up sticking around the hotel, having a bowl of Tibetan egg drop soup on the roof terrace. It was quite good, but I added a dash of Tibetan chili oil, which transformed my pleasant soup from the mildness of the Dalai Lama to the hot-tempered ruthlessness of the Gang of Four. A mistake made, a lesson learned -hot damn!

I returned to the room to give Sus another opportunity to head outside. We had wanted to return to Swayumbunath to be there for the 4pm Buddhist prayer service at the monastery next to the stupa. Susanne said no way and told me to go on my own, which I resisted at first. Again she insisted, so I agreed, shut off the lights once again, and began the trek through Chhetrapati and across the Vishnumati river to Swayumbunath. The climb to the top was much harder then I remembered. Perhaps it was because I was starting my trip up late in the day, with the sun bearing down on me. Anyway, I was popped by the time I reached the stupa at the summit, and I dropped myself by the railing to recover my breath. It was about 3:30pm, and I could hear the monks making a racket in the monastery. I entered the temple and stood in front of their large golden Buddha, who towered a good 10 feet above me. The chanting and music was emanating from behind the Buddha, so I assumed that the ceremony was in a private chamber. Then, about half a dozen Japanese tourists appeared from around the corner. I decided to go from where they came to see what I could find.

The monastery was certainly not designed for tour groups, I soon concluded. It was painfully obvious: around the corner was a long thin corridor, and at its centerpoint stood a door to the right, which led to the main prayer sanctuary. The monks were in the middle of a service there, and a huge group of tourists, mostly Asians, had jammed themselves around the doorway to get a view of the service. I decided it was hopelessly crowded, so I found a another corridor that ran parallel to the sanctuary and positioned myself by a window that opened up into the sanctuary at its midpoint. It would have been the perfect observation spot if it hadn't been for a thin curtain on the other side of the window that obscured the view. Nevertheless, I stayed for a while to listen and peer between the curtains to watch the monks perform their rites.

Then, I saw the entire tour group enter the sanctuary and walk through its center, taking pictures of the monks with flash cameras. It seemed rather rude, but the monks didn't even miss a beat. The good news was that the tourists' intrusion had opened up the space around the main doorway, so I made myself comfortable in the corridor and enjoyed the rest of the ceremony. The monks performed a cycle of activities, starting with a round of low-toned chanting, then a drink of butter tea from large bowls, a blast of horns and cymbals, and then back to more chanting. At one point, they broke out a pair of Tibetan alpine horns, which created tones so low that the floorboards rattled. There were also many young monks in training, probably around 10 years old or younger. Most of them were sitting off to one side, trying to keep up with the chanting. One boy served as a waiter, vigilantly refilling the monks' bowls with fresh butter tea. Another boy swept the floor, though instead of dragging the broom along the ground, he pushed it ahead, which seemed to make the task more difficult than it needed to be. Perhaps that was the whole point.

It was now well past 4pm. When I returned outside to the stupa, I could see dozens of rhesus monkeys, apparently reclaiming Swayumbunath from the tourists. Being territorial primates, they would screech at people who got too close to their space. At one point I wanted to walk between two chaityas, but when I tried, the monkey who stood guard on one of them showed me her teeth and leaned toward me. None shall pass, apparently. By 5pm, I was growing tired of playing Jane Goodall, so I began the 30-minute walk back to the hotel.

Susanne was half asleep when I arrived, so I sat downstairs for an hour, reading the International Herald Tribune and writing in my journal. When I returned to the room , she was awake and getting dressed, apparently feeling significantly better. Her fever had subsided and she was hungry, so we had dinner downstairs. I had more momo soup and some fried rice, while Susanne stuck with plain rice and lemon tea. I also had a Tibetan desert of hot rice pudding topped with cold custard and raisins. It was very good. The rest of the evening was spent reading, writing and talking about tomorrow's plans. Considering Susanne's earlier condition, I was glad to see that the next day was going to have a plan in the first place.

I slowly strolled the main road, talking it all in as I observed the crowds. The noise level increased steadily the deeper I went, until it peaked at a huge square and intersection. I had found Asan Tole, a major gathering place for commerce and religious ceremonies. Asan Tole is the crossroads for six major streets, always jammed with shoppers, merchants, and worshippers, no matter the time. Situated in the middle of the square was a temple to Annapurna, the goddess of prosperity and abundance. Whether Annapurna brought prosperity to Asan Tole, or Asan Tole brought in Annapurna to celebrate its prosperity, who's to say. There were also two other temples, both very small. I didn't recognize the god in one of them, but the other shrine's elephant-headed deity gave it away instantly as a Ganesh temple.

I slowly strolled the main road, talking it all in as I observed the crowds. The noise level increased steadily the deeper I went, until it peaked at a huge square and intersection. I had found Asan Tole, a major gathering place for commerce and religious ceremonies. Asan Tole is the crossroads for six major streets, always jammed with shoppers, merchants, and worshippers, no matter the time. Situated in the middle of the square was a temple to Annapurna, the goddess of prosperity and abundance. Whether Annapurna brought prosperity to Asan Tole, or Asan Tole brought in Annapurna to celebrate its prosperity, who's to say. There were also two other temples, both very small. I didn't recognize the god in one of them, but the other shrine's elephant-headed deity gave it away instantly as a Ganesh temple.  Tuesday, November 19:

Tuesday, November 19: I stood awhile by a massive spice shop, inhaling the fumes of the essential oils as men used mortars and pestles to grind cumin, tamarind seeds, anise and coriander. Somehow I managed to get into a brief argument with a bicycle rickshaw-wallah who insisted that I had no business walking around on such a nice when I could instead be enjoying his services as my chauffeur for the day. Once he had moved on, I took advantage of the hustle and bustle of the square and took numerous pictures of people going about their business. Vegetable vendors were the easiest target, and only one of them asked for baksheesh in return.

I stood awhile by a massive spice shop, inhaling the fumes of the essential oils as men used mortars and pestles to grind cumin, tamarind seeds, anise and coriander. Somehow I managed to get into a brief argument with a bicycle rickshaw-wallah who insisted that I had no business walking around on such a nice when I could instead be enjoying his services as my chauffeur for the day. Once he had moved on, I took advantage of the hustle and bustle of the square and took numerous pictures of people going about their business. Vegetable vendors were the easiest target, and only one of them asked for baksheesh in return.  From Asan Tole I headed southwest to Kel Tole, a much smaller square that bustled with activity, despite its size. As I continued, I noticed a gate and a passageway to my right which appeared to lead to some kind of courtyard shrine. I walked in and there in front of me was a magnificently ornate, two-tiered pagoda, guarded by statues on pedestals and a collection of smaller chaitya shrines. A group of eight men were sitting in a semicircle among the pillars and shrines. They were performing a puja of some sort, throwing rice into a wood and charcoal fire. The men were sporting what appeared to be armor-like vests and crowns that distinctly looked like Burger King paper crowns. To the left, three women in saris chatted away while filling several hundred small pottery cups with rice and drops of tika powder. And just behind them, a huge flock of pigeons swooped and swarmed as local devotees through offerings of corn in their direction, which the pigeons would dive for with every handful.

From Asan Tole I headed southwest to Kel Tole, a much smaller square that bustled with activity, despite its size. As I continued, I noticed a gate and a passageway to my right which appeared to lead to some kind of courtyard shrine. I walked in and there in front of me was a magnificently ornate, two-tiered pagoda, guarded by statues on pedestals and a collection of smaller chaitya shrines. A group of eight men were sitting in a semicircle among the pillars and shrines. They were performing a puja of some sort, throwing rice into a wood and charcoal fire. The men were sporting what appeared to be armor-like vests and crowns that distinctly looked like Burger King paper crowns. To the left, three women in saris chatted away while filling several hundred small pottery cups with rice and drops of tika powder. And just behind them, a huge flock of pigeons swooped and swarmed as local devotees through offerings of corn in their direction, which the pigeons would dive for with every handful.