|

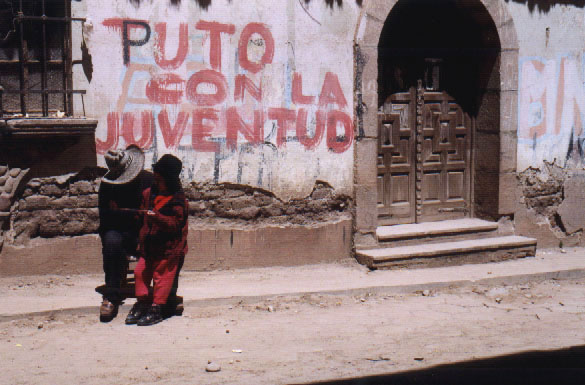

| A father and son sit outside their Copacabana shop |

Butch: Well, you know, it could be worse. You get a lot more for your money in Bolivia, I checked on it.

Sundance: What could they have here that you could possibly want to buy?

Butch: All Bolivia can't look like this.

Sundance: (infuriated) How do you know? This might be the garden spot of the whole country. People may travel hundreds of miles just to get to this spot where we're standing now. This might be the Atlantic City, New Jersey of all Bolivia, for all you know.

Butch: Look, I know a lot more about Bolivia than you know about Atlantic City, New Jersey, I can tell ya that.

Sundance: Ah-hah! You do, huh? I was born there. I was born in New Jersey, brought up there, so...

Butch: You're from the East? I didn't know that.

Sundance: The total tonnage of what you don't know....

Our original plan for today was to check out of the Hostal Cúpula and catch a boat to Isla del Sol, where we would spend the night before heading to La Paz tomorrow afternoon. But as we went to bed yesterday, shivering from yet another unforgiving Titicaca night, Susanne and I agreed that sleeping over on the island would probably be more cold than we could bear. "I can't wait to sleep under the stars of Titicaca" quickly changed to "I don't want to get any colder than I already am." Our new plan was to stay one last night at Hostal Cúpula and visit the island as a long daytrip.

After eating breakfast we headed into town down Avenida 6th de Agosto, where we stocked up on food supplies for the day: vanilla crackers, wafers, giant roasted peanuts and a bag of pasankalla, the local gargantuan variety of choclo popcorn coated with carmel. There shouldn't be a problem buying more food on the island, but neither of us wanted to be left totally high and dry just in case we weren't so lucky. Down at shore, though, I noticed things were particularly quiet - there were no boats waiting to be taken out, nor any tourists looking for transport to the islands.

We approached the ticket office that sold passes for the daily 9am tour of Isla del Sol. Several men stood inside a kiosk and shook their heads in frustration. "No boats," they said. No boats? The men spoke little English and neither of us had an complete grasp of what they were saying, but it appeared that all of the morning trips had been canceled due to high surf and winds.

"Nada hoy?" I asked.

"One o'clock, maybe," they replied, though with little confidence. We were now stuck in Copacabana with little left to do except kill time and wait. Today was going to be a long day.

Susanne and I briefly stopped by the cathedral, where we mulled around the plaza visiting souvenir carts. The cathedral was deserted compared to yesterday's circus, and as far as I could tell we were the only outsiders around. Yet once again we felt the icy stares of the local campesinas as we casually browsed from one souvenir cart to another. Even the women selling the trinkets didn't seem to care to have us hanging around - how on earth could they expect to stay in business like this? As hard as we tried to feel comfortable here, someone always seemed to make it clear to us we weren't very welcome.

Neither of us could come up with any good solution for wasting away the day, so we returned to the hotel to drop off the unused supplies for Isla del Sol and picked up our journals and sketchbooks. Perhaps we could whittle away the hours by writing - lord knows how far behind we've both gotten this week. I suggested we return to the Inka Wasi for a long lunch; the meal we'd had there yesterday was quite good and the atmosphere seemed suitable for writing. We walked along the road in an attempt to find the restaurant. At first I thought we were a block or two off course, for its gated garden was nowhere to be found. I then noticed a large wooden door that was bolted shut and sealed with a large padlock. The door was shaped like the restaurant gate - the Inka Wasi was closed today.

"If this place is closed, that means the only decent place to eat in town is back at our hotel," I said.

"What does Lonely Planet suggest?" Susanne asked.

Susanne and I sat in the garden, where we ordered chicken and egg sandwiches. As we waited for our food we watched three or four large groups of tourists walk down the avenida. Often lugging huge backpacks, sometimes wearing shorts and sneakers, the tourists were as conspicuous and numerous as ants at a picnic - and as unwelcome, at least in the eyes of many of the locals.

"We knew it would be like this," I said to Susanne, shaking my head as another group of backpackers walked by. "The Lonely Planet book even says that the Aymara

"Yes, I know," she replied. "It just bothers me that there are places like this where everyone there would have preferred it if we'd never come in the first place."

"I wonder how much of this is because of recent tourism and how much of this is inherent in the culture," I continued. "If we had come here five years ago, would the locals have minded so much? Would they see us as an annoyance or as a novelty? As it is, the Aymara don't always understand how we gringos can afford to leave our livelihoods and our families behind in order to waste our time traipsing around the world. And now that the tour books declare Bolivia as one of the last unmolested regions on earth, we're all suddenly drawn to it, and therefore wreck the pristine environment we've come to appreciate."

"But it's not always like that," Susanne responded. "Think of our visit to Laos. Five or ten years ago, no one visited Luang Prabang. When we went last year it had clearly been 'discovered' by tourists already, but the locals were the kindest, the friendliest people we ever met."

"And it's only going to get worse," Susanne noted. "Look at how many gringos are already in Copacabana. It's too beautiful a place for tourists not to visit it. I just hope the residents can make it work for themselves."

It's not often we've ever felt guilty about our travels over the years; visiting hilltribes in Thailand might be the only major exception. We found a similar pattern of events here: an ancient culture with a fascinating history and legendary handicrafts begins to attract pioneering visitors. The pioneering visitors bring hard currency, which cause some of the locals to change the environment enough to make it more welcoming to future visitors. With each new round of visitors, more services and amenities are added as more traditions fall by the wayside. In the end the local population is divided among those who wish to take advantage of the tourists and make money off of them, and those who steadfastly hold on to their old ways and insist their community would be better off without them. Tourism's Law of Cause and Effect. Who's right and who's wrong? They both are. We all are. Copacabana has developed the reputation for being a quaint little resort community, yet few too many people involved in promoting it ever bothered to ask permission of its residents. It's a tug-of-war between commerce and tradition and we're stuck smack in the middle of it, standing in the mud.

Neither of us were very satisfied with our sandwiches so we strolled up the street to the Inti Huayri café to relax over a couple of cokes. As we walked to the café I noticed several other restaurants were also named Snack 6th de Agosto. Suddenly everything made sense to me. Before travel books began writing about Copacabana there had probably been one Snack 6th de Agosto in town. Lonely Planet then published a glowing recommendation of the restaurant and explained you could find it along its namesake, Avenida 6th de Agosto. As soon as the book made its way to Copacabana, every other restaurant along the avenida changed its name to Snack 6th de Agosto. Who knows if we ate at the original Snack or at a mere poseur 6th de Agosto? Either way the confusion served as a simple example of our lingering theory: Tourism's Law of Cause and Effect.

Back at the hotel we caught an early dinner at the restaurant. Since tonight was to be our last in Copacabana, I splurged for an order of salmon trout broiled in lemon juice. We finished eating soon after 7pm and wondered what we would do for the rest of the evening. I remembered the hotel showed videos each night in the common room. Susanne asked someone at the front desk what was playing tonight and he replied with the linguistically ambiguous "The Mascara." After poking her head into the common room she realized the video in question was going to be "The Mask," with Jim Carrey. Neither of us had seen it before so we decided to watch it.

As we walked outside to our room we noticed that the skies were totally clear. Thousands of stars glittered above us. "Maybe now we can find the Southern Cross," Susanne said. Both Susanne and I were eager to spot the constellation at least once during our visit to South America, yet every other night in Copacabana had been cloudy. We then noticed a young Aymara man walking outside the hotel. Susanne quickly approached him and asked him to point out the constellation for us. "Dónde está le Cruz de Sud?" we asked, hoping Cruz de Sud would mean "Southern Cross" to him. "Está no aquí," he replied. "Onze, onze y media a noche." It sounded like it wouldn't rise in the sky until after 11pm, but he pointed north instead of south, which confused me. We'd have to try again later, I guess.

After securing our daypacks in the room we returned to the common room, where a Norwegian couple and a longhaired American in his early 20s already occupied the main couch. Susanne and I grabbed two chairs next to a tall Dutch man who was showing off the largest black cowboy hat I had ever seen. "I have a really big head," he said, "so I asked them for the largest hat in the shop." The movie began promptly at 7:30pm: English with subtitles in Spanish. I've never been a big Jim Carrey fan so at first I paid little attention to it, spending some time in the adjacent kitchen playing a Spanish guitar quietly while boiling a kettle of tap water. The water boiled for 30 minutes - plenty of time to kill any nasty germs, I hoped. I brought out matés de coca for both Susanne and the Dutchman, while I steeped a blend of maté de manzanilla (mint tea) and coca leaves. Despite the habit I developed in Cusco, I was never a real fan of the taste of maté de coca, so the mint helped soften some of the bitterness.

Watching the movie was a great way to wrap up the evening, especially after having such a disappointing day. I probably learned more Spanish from reading the subtitles than I had in the last nine days of traveling. Scott, the longhaired American, picked up the guitar after the film ended and played it as the group trickled off to their rooms. Susanne and I mentioned to the Dutchman we had been looking for the Southern Cross but hadn't found it yet. "I think I know where it is," he said, offering to give it a shot. We stepped outside in the frigid Altiplano air and looked around. "There," he said, pointing to the southeastern sky. High over the city valley I saw a large, bright constellation in the shape of a kite - the same constellation I had seen a week earlier on our bus ride out of the Sacred Valley. "I am pretty sure that is it," he said, tilting his cowboy hat. So we had found the Southern Cross already and just hadn't realized it.

We stared at the constellation for a few moments. "Well, we've seen the Southern Cross now," I said. "Where do we go now?"

"La Paz," Susanne replied.

Running out of options for this small town, we decided to visit Copacabana's market, a few blocks from the cathedral. Compared to other markets we've seen in South America, Copacabana's was rather restrained. On one side of Avenida Pando campesinos sold fruit, vegetables and fresh bread from wooden carts, while butchers and clothing stalls lined the other side. A middle-aged cobbler hammered sandals out of worn strips of tire rubber. Not many people actually seemed to be buying anything; instead people stood around their stalls, chatting away and chewing coca. Perhaps we had missed the action earlier this morning - or perhaps there was no action to be found at any time of day. The quiet morning market did little to alleviate our restlessness.

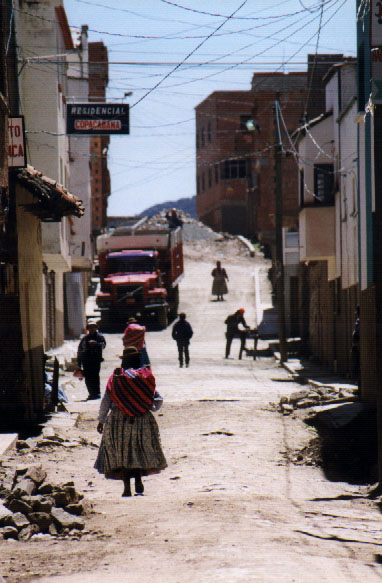

Aymara campesina, Copacabana

I pulled out our guidebook and looked for a restaurant. The book strongly recommended "Snack 6th de Agosto," which we had passed numerous times along the avenida. Snack 6th de Agosto was a typical Copacabana garden restaurant: ample outside seating and a few tables indoors as well. The menu, unfortunately, was typically Copacabana as well - fried chicken, fried meat, fried fish; chicken sandwich, egg sandwich, cheese sandwich. There were no culinary masterpieces to be found in Copacabana, at least not today in this part of town.

Avenida 6th de Agosto, Copacabana  of Titicaca are often known to be cold to outsiders."

of Titicaca are often known to be cold to outsiders."

"You're absolutely right," I answered, "but I wonder if that's partially because the people of Laos have always had contact with the other communities around them. We tourists were probably seen as just another group the Lao could get to know and do business with, so there's no hard feelings. Here around Titicaca, the first group to visit the Aymara were the invading Quechuas of the Inca empire. Not long after that, the Spanish came in and took over. No wonder they're suspicious of outsiders - what good things have outsiders ever done for the people here?"

Campesinas crossing the street, Copacabana

We had intended to journal inside the café but the tight quarters coupled by a loud conversation between the owners and some visiting friends changed our minds. We instead quietly sipped our Cokes, listening to Bolivian marching band music on the radio. Neither of us really wanted to waste the entire day without getting at least some amount of writing done, so we again departed in search of another setting, another café where we could spread out and work. Down the road, not far from the lake, Susanne and I discovered yet another Snack 6th de Agosto. This particular Snack had a large, deserted garden café with folk music playing over the speaker system. I sipped a bottle of Pacena beer - my first Bolivian beer, I think - and huddled over my journal, hoping the words would begin to flow. We managed to get a little writing done but our restlessness soon returned. "Perhaps this just isn't meant to be," I said to Susanne. We must have passed the time somehow, though, for it was now around 4:30pm. For a slow day it seemed to have gone by rather quickly.

A feeble attempt at writing on a cold Copacabana afternoon

|

|

|

|

|

|

|