|

Andy posing along the Bolivian altiplano,

with Huayna Potosi looming in the distance |

Butch: Kid, the next time I say, "Let's go someplace like Bolivia," let's go someplace like Bolivia.

Sundance (looking over the cliff): Next time. Ready?

Though our alarm clock wasn't set to go off until 8:30am I woke with the sun a little before 7 o'clock. We really had no reason to get up very early; our bus for La Paz would depart at 1:30pm, giving us the entire morning to hang out at the hotel. I remembered seeing a sign at the Cúpula restaurant saying it was closed for cleaning on Tuesday mornings. Indeed, when I went to the restaurant for breakfast I was told the dining area was closed, though I could sit on the outside patio and have some coffee. The brisk wind chill coming off Lake Titicaca discouraged me from accepting their suggestion. I'd have to find breakfast in town instead.

Back in the room I left a note for Susanne, who was still asleep:

Sus- Going to town to find food and cash a traveler's cheque.

Restaurant upstairs is closed this morning. I'll be back around 9. -ac

Susanne was never much of a breakfast person so I figured she would mind me slipping out early for some grub. I walked down into town to Avenida 6th de Agosto, where I could find the greatest concentration of restaurants (though "concentration" might be too strong of a word for a town of this size). I soon wondered, though, if Tuesday morning cleaning was a tradition in Copacabana because most of the cafes were conspicuously closed. I eventually resorted to Snack 6th de Agosto - the one where we had lunch yesterday - and ordered their Desayuno Americano, a standard 10 boliviano plate of two eggs, toast, jam, butter, papaya juice and coffee. The papaya juice was especially good - thick as molasses. But just as I wrapped up my breakfast I was shooed away by the owners, who (surprise) were closing the restaurant for cleaning.

Before returning to the hostal I also needed to cash a traveler's cheque. Since we were checking out of our room we would have to pay the bill of 300 bolivianos, about $55, for three nights' stay. Susanne and I still had around 250 bolivianos on hand - plenty of money to get us settled in La Paz, but not enough to wrap things up at the Cúpula. The Lonely Planet book said there were only two reliable places to get cheques cashed in Copacabana - the Hotel Azul and the bank next door to it. The bank appeared boarded up and abandoned so I tried the Azul first. The man at the reception desk told me they didn't change money there, but a new casa de cambio had just opened up down the street. I went to the new bank and stood in line with two people as the bank manager swept the floor inside in preparation to open for business. Around 8:45 a guard allowed the first customer to come in; ten minutes later I was given the go-ahead to enter the door. Before I even reached the counter, though, a bank employee informed me that they would only exchange cash here. No traveler's cheques at a casa de cambio? I asked if there were any places in town that would take my cheque. "Hotel Azul, señor," he replied. I guess I'd have to pay our hotel bill with a credit card after all.

Susanne was getting up when I returned to the Cúpula around 9:15am.

"Did you see my note?" I asked as I entered.

"Yeah," she replied, "but I wasn't completely awake when I read it. I thought it said, 'Sus, I'm going into town to get drunk.'"

"Well, you know me," I responded, laughing. "Always in need of a few beers before breakfast."

While she got dressed I went to the man at the front desk to make sure I could pay with a credit card. "No problem," he said, taking the plastic from my hand. He then told me that there would be no credit surcharge for use of the card, as had been the case in Peru. I guess I'd just have to see about that when I got back to the US. (As it turned out he was right.)

Susanne and I packed up our bags and moved into the hotel's public room just after 10:30am. We could stay there as long as we wanted, so that gave us about two hours to make a fresh pot of maté de coca and write in our journals. We were joined by Scott, the longhaired American who had watched the movie with us the previous night. Scott was a Californian college student from Catalina Island who had been traveling around Brazil and Bolivia for the last month and was getting ready to catch a bus back to La Paz before flying home. Scott grabbed the Spanish guitar off the wall and began to play songs. "Here's a song I wrote for my mother," he said as he strummed his melody. He was pretty good and not at all shy about demonstrating his talents.

"I'm a big Pink Floyd and Led Zeppelin fan," he continued, playing a song from The Wall.

"Let me give a shot," I said, asking for the guitar. I re-tuned the guitar to open-G and started to play the song "Fearless."

"Old Floyd!" he smiled. "Very cool - Meddle is a great album."

We both fiddled around on the guitar for while, with Scott playing original tunes and me showing off my extended repertoire of Zeppelin and Rush songs. Before we realized it, 1pm was just around the corner. The three of us, joined by the Norwegian couple, descended into the city to catch our buses.

"Which bus are you on?" Scott asked.

"Vicuña Tours," I said. "What about you?"

"6th de Agosto Tours," he replied.

"Well," I said, "since it appears this is goodbye, you better tell us the name of your band so I can remember it when you make it big."

"And," he said, matter-of-factly.

"And," I nodded. "OK, I can remember that..."

As Scott and the Norwegians headed to one corner of the main plaza, Susanne and I walked to the bottom of Avenida 6th de Agosto, where we had originally been dropped off by the bus from Puno. There was no bus there yet, so I asked a local merchant where it was. "No bus aquí," he replied, looking at our ticket and pointing to a row of buses on the far end of the plaza. Susanne and I walked across the dusty, windswept plaza to a pair of buses, both sporting Puno-Copacabana-La Paz signs. No one had boarded either bus yet, so we waited around for a few minutes. A familiar face then leaned out of a hotel doorway: it was the red-bearded fellow from San Jose who had shared our minibus to the train station in Cusco. "Good to see you," he said in English with a noticeable Spanish accent. We talked for a while and discovered he was beginning a two-year round-the-world trip.

"Where are you from?" I asked.

"Costa Rica," he replied. Aha - the San Jose I saw on his luggage tag wasn't in California. It was the capital of Costa Rica. Never assume anything, I suppose.

Around 1pm passengers started to board the second bus. I showed our ticket to an old man and he instructed us to get on. I wasn't entirely convinced he had been paying attention to what was written on the ticket, so once we had settled onto the bus, I asked, "La Paz bus?" The dozen or so people on the bus all shook their heads no. "Puno bus." Susanne and I quickly tugged our backpacks off the storage racks and climbed aboard the second bus. As we waited a second ticket man inspected our receipt.

"Not this bus," he said. "Segundo bus."

"No, not segundo bus," I replied as he motioned for us to re-board the Puno-bound bus. Susanne and I were both rather annoyed with our predicament to say the least.

A young travel agent then came from out of her office and looked at our ticket. "You must take Vicuña Tours," she said. "Follow me." Once again we walked across the plaza to the place where I had originally asked the merchant where our bus was. Lo and behold, the same bus we had taken three days early was now sitting in front of his shop. "Vicuña Tours," the travel agent smiled as she escorted us onto the bus. Now we could get on our way.

Our bus departed around 1:40pm, half full with backpackers and a handful of Bolivian tourists. The bus turned away from the lake and drove past the cathedral. Less than 50 yards past the cathedral we were suddenly in farmland, freshly plowed and swarming with sheep, goats and piglets. "I had no idea this was back here," I said to Susanne. "I wish we'd gone for a walk." After submitting our names to the police departure checkpoint the bus weaved high up and around they Copacabana valley. We noticed a film crew shooting in a red clay canyon not far from the road.

"I wonder if Newman and Redford will ever shoot another film together," I pondered.

"Only if the script is right," Susanne replied.

I pictured Butch and Sundance racing up the red clay hillside, trying feverishly to get away from the posse of trackers. "We'll jump!..." "Like hell we will!..." I could hear them bantering all the way up.

|

| Lake Titicaca and the Cordillera Blanca |

As the bus drove higher up the valley an incredible site appeared before us: the hauntingly blue waters of Lake Titicaca flanked by a backdrop of the snowcapped peaks of the Cordillera Blanca. "Get a picture!" I barked enthusiastically. Susanne leaned out the window and snapped a photo. "People will think we used a blue filter for this," she said, staring at the mountains. The bus now descended quickly towards the lake. I could see a river-thin piece of the lake being crossed back and forth by ferries and barges. We had reached the Straits of Tiquina, which separates Lake Titicaca from its little sister, Lake Huinaymarca. Our bus would take a maritime shortcut across the straits between the towns of San Pablo and San Pedro in order to save time on our way to La Paz.

At the waterfront we were told to exit the bus and pay one and a half bolivianos to the Bolivian navy in order to cross the strait. "Bolivian navy?" I thought to myself, not wanting to argue with sea-faring officers from a landlocked nation. As our bus was loaded onto a barge, the dozen of us boarded a small launch. A pair of young Israeli women said across from us, one of them looking a little queasy. "I hate boats," she said. "I never wanted to take one again in Bolivia. No one told me we'd take a boat on this bus ride."

"It's a short trip," I promised, trying to talk her through the five-minute crossing. "Because we're crossing here we'll save at least two hours of driving time going around the widest part of the lake. So where in Israel are you from?..."

|

| Boarding the Bolivian navy transport boat as our bus is ferried across Lake Titicaca |

Before we knew it our sailing time on Lake Titicaca had come to an end, and the Israeli had managed not to throw up on any of us. Our bus arrived on the shore a few moments after our landing. It quickly drove off the barge and parked on the far end of a small plaza. While Susanne and the others walked to the bus I paused at a street vendor selling empanadas.

"Tiene empanadas con queso?" I asked.

"Sí," the shy campesina replied.

"Cuanto cuesta para una empanada?" I continued.

"Uno boliviano," she answered. I handed over a boliviano coin and received a bagful of four empanadas in return. Not what I expected, but it was more than enough food to keep us snacking for the next two or three hours to La Paz.

Susanne managed to doze off as the bus bid a final farewell to the shores of Lake Titicaca. The highway continued along the bleak Altiplano plateau as freshly plowed farmland stretched across the landscape, mile after mile. Around 3pm we encountered a barricade obstructing the highway: the road was under repair up ahead, so we'd have to drive on a dirt road parallel to the renovation work. Our bus slowed to a crawl, kicking up incredible amounts of dust and debris as it traversed miles of dirt, rubble and mud. Images of luggage and backpacks thrown skyward crisscrossed my mind as the bus heaved, crashed and twisted from the rocks and potholes below. And throughout the racket, Susanne slept like a cat. I envied her serenity as I held on for dear life.

The bus returned to the highway pavement and continued its eastward track to La Paz. How much further would we have to go? The owner of the Hostal Cúpula had commented that morning we should arrive in La Paz no later than 5:30 or 6pm, though if we were lucky we'd be in town by 5pm. According to those predictions we had at least an hour to go. But La Paz seemed so far away: apart from the glacial peaks of Huayna Potosi to our north and Nevado Illimani to our east, all I could see around me was more flat Altiplano farmland. Then again, I'm pretty sure that Nevado Illimani stands just east of La Paz - somewhere between here and that massive mountain was the Bolivian capital, below the horizon in a deep crater-like valley.

Susanne awoke as the bus driver played a game of cat-and-mouse with another bus, speeding up and passing it every time the rival bus passed us. As we made our third or fourth pass, a loud popping noise shook the bus. I realized we were all leaning down and to the left just as the smell of burnt rubber filled the cabin. Susanne and I looked at each other. "Flat tire," we said in unison. The bus limped to the side of the road and parked in the dirt. The driver opened the door and waved us to go outside. Donning our jackets and cameras, Susanne and I stepped out into this barren landscape. Apart from the sounds of a light breeze and the occasional passing bus, all was quiet along the Altiplano. Far to our right a farmer tended his land as his sheep grazed in a pasture. To our left was more barren farmland, with Huayna Potosi standing majestically in the background. And somewhere straight ahead - how far I could only guess - La Paz patiently waited for us. For now, though, we were stranded in the middle of nowhere.

As our driver removed an extra wheel from the right side of the back axle, Susanne and I climbed along an embankment along the road. "Despite all of our travels," I said, "we've never gotten a flat tire. I guess that streak had to come to an end. Might as well be in Bolivia, I guess."

"Oh, this shouldn't take to long," Susanne replied. "We might as well enjoy it."

|

| Susanne enjoys the diversion along the Altiplano as our bus driver changes the flat tire |

She was right: at the rate our driver was changing the tires we'd probably be on the road in less than half an hour. The flat offered us an added diversion, unexpected as it was, to take pictures and hang out in the countryside. Susanne and I snapped some photos of each other along the road and in front of Huayna Potosi. I squinted as my eyes adjusted to the powerful rays of the Altiplano sun, sinking lower to the northwest. I wondered if we would get to La Paz before sunset. Probably not.

By 4:20 we were on our way again, barely 20 minutes since the flat. Over the course of the next 10 minutes the deserted farmland transformed into streets increasingly crowded with buildings, pedestrians and traffic. I read a storefront sign to my left: "Bodega El Alto." El Alto? El Alto is the outlying area of La Paz, along the upper lip of the La Paz valley. The entire time our bus was incapacitated I had been convinced we were at least an hour from the closest city. In reality, we were probably no further than 30 minutes from downtown. But where was La Paz? There was still no sign of its famous, overcrowded lunar landscape.

The bus squeezed through traffic jams of minibus taxis and vegetable carts before reaching what appeared to be a tollway. A few moments after passing through the tollbooth the buildings to our right thinned out, revealing an immense, crater-like gash in the Altiplano extending for miles to the east. One thousand feet down into the center of this deep bowl we could see the crammed city of La Paz, a maze of skyscrapers and adobe-brown apartments coating the entire valleyside. Most of the people inside our bus rushed to the right side, staring out the windows in awe. I've heard of people describing this descent into La Paz as spectacular, but spectacular doesn't do this view justice. Having spent the last two hours crossing the flattest of barren countryside, the La Paz valley was a sudden tectonic jolt, as if the earth itself had opened up and revealed a fiery geode in its core. The cityscape was nothing short of stunning.

|

| The La Paz valley as seen from the altiplano plateau |

The bus descended clockwise into the valley, limping along at 30 miles per hour due to its paucity of tires. Several cars and buses honked at us as they tried to pass the bus, frustrated by our pace. Large billboards advertising everything from American Airlines to the Intel Pentium II Processor loomed over the highway. "Ahh, the big city," I thought to myself.

I didn't know what to expect from La Paz. I knew it was overcrowded and polluted; many people had warned me of "a lot of poverty" as well. Perhaps the most interesting first impression had come from Scott at the Hostal Cúpula. "Wherever you go you'll see a lot of protesters," he said, "and they'll be trailed by police in full riot gear: shields, helmets, tear gas launchers and all. But it's really no big deal..." I couldn't imagine the capital of Bolivia being a hotbed for political activism and freedom of assembly - Bolivia still boasts a record of one of the highest number of coups in the Western Hemisphere. But coups, Bolivians now hoped, were a thing of the past. The last several elections have gone smoothly, though the current president, General Hugo Banzer, was himself a former military strongman. Perhaps allowing freedom of protest was one of his affirmations of political legitimacy; perhaps we'd soon find out how legitimate it really was.

La Paz at rush hour was a shock to the system, especially after having spent the last several days in a lakeside village. The streets were teeming with activity. Businesspeople carried briefcases and chattered on cellphones while trying to hail a taxi. Street children with wooden shine boxes clamored to find a dusty pair of shoes they could clean for a couple of bolivianos. Campesinas sold American cigarettes and magazines, their infants wrapped tightly to their back in colorful blankets. La Paz was a city of both the Old World and New World, though I don't only mean in an architectural sense. Everywhere you looked you could see well-dressed urbanites and traditionally costumed campesinos competing for sidewalk space. I had only been in town for a few minutes, yet just through looking out my bus window I could see La Paz was a city divided, culturally, linguistically and socially.

Our bus squeezed through the tight colonial avenidas, just missing the thicket of telephone and electrical wires suspended over every intersection. For whatever reason I noticed the wires before anything else here; they hung over every street like turn-of-the-century cable car's power lines. Each time our bus turned a corner I expected our luggage strapped to the roof would be swiped away by a snapping cable, sending showers of sparks to the ground and setting our belongings on fire. But before such a conflagration could begin we pulled over along Calle Illimani: "I think our hotel is somewhere along here," I said to Susanne. Looking out of the left side of the bus I saw a painted white sign with the words "Hostal Republica." By some strange coincidence our hotel was the official downtown drop-off point for Vicuña Tours: door-to-door service free of charge. Once we were able to get our backpacks off the bus roof we only had to cross the street to settle in for the rest of the week.

Susanne and I dropped our bags in the reception room while I asked about our reservation at the front desk. When we called the hostal from Copacabana they told us we might have to take a room without a bathroom; fortunately a doble con bano privado was still available at $24 a night. A women working next to the front desk introduced herself as the resident tour agent. She showed me a list of prices for local tours, including a $15 day trip to the ancient ruins of Tiwanaku. Tiwanaku was high on my to-do list for La Paz so I told her I'd talk with her tomorrow morning about tour arrangements for either Thursday or Friday.

A young man brought us to our room on the far left corner of a beautiful open courtyard, decorated with checkered marble tiles and a wide staircase to the right. The turn-of-the-century Republica was once the private villa of a former Bolivian president, though for some time it's been maintained as one of the most charming colonial hotels in La Paz. Our room was long and thin, with two beds, large windows and a lovely view of the courtyard. The bathroom unfortunately smelled like rotten eggs. At first I thought it simply needed to be cleaned, but as I tested the sinks and the toilet I realized it was the sulfur-heavy water supply that was causing the mild stink. "We'll just have to keep that door closed," I said, wriggling my nose at Susanne.

By the time we had settled into the room I noticed the sun was getting ready to set. "Let's go for a walk," Susanne suggested. Plaza Murillo, La Paz's most picturesque public square, was only a few blocks away, so we grabbed our cameras and walked single file along the slim sidewalk. Even here along our modest avenida there was a continuous flow of taxis and businesspeople walking from work. One thing I did notice was the traffic lights: people here obey traffic lights! Susanne and I have been to so many cities like Cairo, Calcutta and Phnom Penh where absolutely no one pays attention to traffic lights, signs, or rights-of-way. La Paz, though, maintained a orderly, yet always high-strung, pattern of traffic congestion. The local cars would speed as fast as they could until they hit a red light, then slam on the brakes until they could again speed off at the next green signal.

Most streetcorners were occupied with campesinas and their meagre convenience stands selling bottled water, cough drops (Hall's Mentholyptus are eaten as candy here), chocolate, cigarettes and empanadas. La Paz has seen a steady influx of rural Aymaras and Quechuas coming to the city in the hopes of fleeing the poverty of the countryside. Many of them, sadly, have only found urban squalor. Most of the campesinas we saw in this part of town seemed to be making a decent living selling goods, but the adobe shantytowns stretching high up the El Alto hillside stood as a constant reminder of the delineation between the very rich and very poor that call La Paz home.

Four blocks west of the hotel we reached Plaza Murillo. Along with being the best place in town to feed pigeons, Plaza Murillo is the heart of Bolivian politics, with its grand cathedral serving as the presidential palace on one side and a bright yellow, Spanish colonial residencia serving as parliament on another side. In the center of the plaza stand towering statues and sculptures dedicated to the glory of Bolivia. Plaza Murillo, though, hasn't always been so noble a place - in fact its very name comes from the Bolivian patriot Don Pedro Domingo Murillo, who was lynched here in 1810. History repeated itself in 1946 when President Gualberto Villaroel was dragged from the palace and hung by a mob off a plaza lamp post. Bolivia has had a long history of shady politics and intrigue, from its revolt against Spain in the early 19th century to the coups of the 60s, 70s and early 1980s. But the 1990s have been a fairly stable and prosperous period for Bolivia: inflation has been cut from five digits to 10% a year and the last several presidential elections were smooth, despite the fact that president Banzer is a "reformed" former dictator himself.

|

| Plaza Murillo, La Paz |

Sunset at Plaza Murillo is an unforgettable experience. Thick beams of light provoked the yellow parliament building to glow in rich, warm hues. Huge flocks of pigeons flew overhead, first settling on the stone balcony of the cathedral, then swooping down to the plaza, then back the cathedral. Those pigeons that remained on the plaza feasted on the showers of corn kernels thrown by families gathered on benches. A little girl stared in fascination at the two frolicking puppies her parents had just purchased. Old men in bright yellow and white uniforms wheeled around carts of ice cream, calling out "Chocolato! Vainilla! Mango!" like peanut sellers at a Yankees game. Plaza Murillo was a tranquil place, perfect for a late afternoon respite.

|

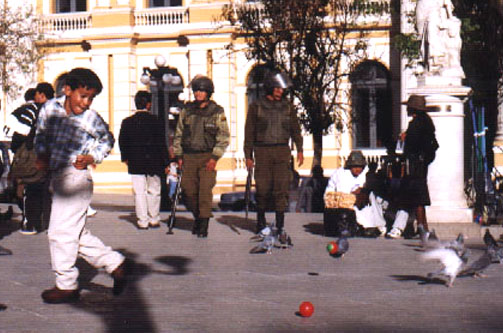

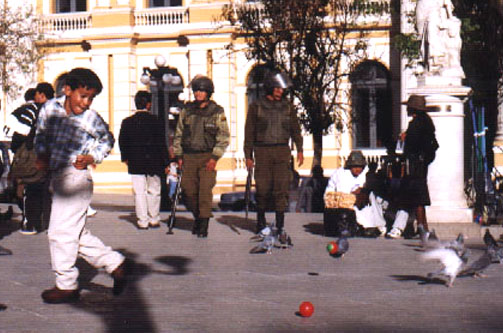

| Military police guarding Plaza Murillo, La Paz |

Yet interspersed among the crowds of grandmothers, young lovers, and schoolchildren were camouflaged policemen, heavily armed with shotguns, tear gas cannons and grenades. Plaza Murillo is Bolivia's White House and Capitol rolled into one, and the government here makes no bones about displaying a little public force. To Susanne and me the soldiers stuck out like sore thumbs, though the residents of La Paz were clearly used to their presence, paying no attention to them. Likewise, the soldiers seemed to spend their time loitering about, leaning against lamp posts and cracking jokes with their armed comrades. The soldiers were just another everyday aspect of life in La Paz, invisible to the denizens of Plaza Murillo - except for Susanne and me, who constantly noticed them lingering in the periphery.

|

| A boy plays kickball as soldiers guard Plaza Murillo |

About three blocks past Murillo we found Pollo Copacabana, a consummate standing-room-only fast food joint. One of first things Susanne and I noticed, though, was the fountain soda machine behind the counter. "Uh oh," I said. "No bottled drinks. Not a good idea." Assuming that we could find another place to eat somewhere around here, we turned the corner and found a much smaller chicken restaurant, the words "Pollo Dorado" emblazoned on a neon sign above. Looking inside I saw a long room with cafeteria seating and grumpy customers huddled over their food - not very appetizing.

"We passed a couple of restaurants by the hotel," I said. "Wanna check them out?"

"We're in no rush I guess," Susanne replied.

After walking the 15 minutes back to the Hostal Republica we found the Restaurant del Sol. Susanne and I entered its courtyard seating area and looked around. A rowdy group of young men occupied two tables pushed together, piling a dozen or so large bottles of Cerveza Pacena on a neighboring table. We stood around for a minute anticipating the inevitable arrival of a waiter but none ever came. The kitchen was located up a small staircase so I started to walk up to see if I could find anyone. As I reached the top of the stairs a waiter stepped outside, staring at me in wonder as to why I was going to the kitchen. Before I could ask for a menu he said, "No food tonight. No chef. Only beer tonight." Plenty of beer, I could tell from the sound of things. I looked at Susanne, a little frustrated. "Well," I said, "there's that other place a block towards the plaza."

The Restaurant Girosol was a mystery from the moment we entered. The front door led us to a high staircase; a large man with a cigar and a limp walked several steps ahead of us, sweating and gasping the whole way up. Inside we found two small rooms. The large man joined another man, also chomping on a cigar, and immediately began a heated game of backgammon over a shared bottle of cognac. A waiter stood behind the bar, leaning on the counter to read the newspaper. He briefly looked up as we entered, then chose to ignore us and read his paper instead. I motioned at him to get his attention for a menu. Again he looked up, staring at me as if I had interrupted him from a pivotal paragraph in the sports section. The waiter briefly left his post behind the bar, dropping a solitary menu on our table.

The Girosol offered typical Bolivian fare: roasted chicken, fried steak, trout, and pork. Susanne and I both ordered the chicken. As the waiter disappeared into the kitchen, Susanne and I looked at each other.

"I think we've stumbled into a mafia joint," I said.

"I know," she replied, "I was about to say the same thing..."

The waiter returned, handing me the menu yet again. "Solamente uno pollo," he said, shaking his head. Leaning outside the kitchen door I saw another cigar smoking overweight man, his white dress shirt covered with a greasy apron. The chef, I presume. I looked again at the menu and asked, "Tiene trucha?" If I couldn't have chicken, hopefully they'd at least have trout. The waiter looked to the kitchen to gauge the chef's reaction. The chef closed his eyes and shook his head. "No trucha," the chef mumbled. "No trucha y solamente uno pollo." Once again I looked at Susanne, looking for a way out. "I think we should go," she said.

We gathered our belongings and stood up, backing out to the steps as both the waiter and chef stared at us. "We had no business in that place," I said as we reached the street. "Let's just go to Pollo Copacabana and get this over with."

After walking by Plaza Murillo for the fourth or fifth time tonight we eventually returned to Pollo Copacabana, crowded as ever. A campesina was selling bottled sodas outside, so I purchased a Fanta and an agua sin gas in lieu of the soda fountain machines inside the restaurant. Susanne and I both order a plate of fried chicken accompanied by greasy french fries, mushy fried plantains shaped like tater tots, and a special sauce blended out of ketchup, mustard and salsa. Gourmet food it wasn't but it would do for tonight.

We walked upstairs in hopes of finding a free table but there was none to be found. Returning downstairs to the counter seating area I noticed two free stools, one being used as a foot rest and another supporting a woman's purse. As I turned to Susanne to figure out how we should ask for the stools in Spanish, the woman with the purse picked it up and put it on the counter, smiling brightly at Susanne as she offered her spare seat. Simultaneously a young man lifted his foot off the other stool, his girlfriend prodding him in the ribs as she smiled at me. The other diners at the counter automatically parted in two, leading us to an oasis of free space. No one would ever do that for me in Washington, I thought to myself. Susanne and I dived into our chicken platters, observing the passing crowds along Calle Comercio through a plate glass window in front of us. As we ate our dinner and talked I occasionally noticed the woman with the purse glancing at us with a big smile as her teenaged daughter pulling at her coat in hopes of going home soon.

After wrapping up dinner we strolled slowly along the mall, its crowds having increased significantly since we first arrived. "Did you see the way that woman smiled at us when she offered us the stool?" Susanne asked. "It's really amazing how one simple smile from a person can form your first impression of an entire city." I'd thought the same thing as well. Even though La Paz was Bolivia's answer to New York or London, almost all the people we encountered seemed gracious and happy to us. It was a marked change from the cold stares we received throughout Copacabana. I knew I was going to like this city a lot.

Back at the hotel, as we got ready for bed we heard the sounds of small explosions in the distance. I actually thought the first one or two bangs might be gunfire, but as they continued for several minutes I concluded they must be fireworks. "At least I think they're fireworks," I said, wondering aloud.

Susanne opened our window and leaned her head out into the courtyard. I heard her ask one of the hotel employees, "Que est la boom boom?" The woman answered her but I couldn't tell what she said.

"Que est la boom boom?" I asked, smiling.

"Well," Susanne replied, "at least I got an answer with it. She said they're fireworks from the campesinos." The local Aymara must be celebrating some kind of ceremony, we concluded. At least the boom booms weren't Boom Booms, so to speak. I climbed into bed, tucking myself under the many layers of alpaca wool blankets, and went to sleep with the echoes of fireworks exploding in the distance.