|

| Cha'lla ceremonies, Copacabana |

Percy the Miner (to Butch and Sundance):

"You've got to get used to Bolivian ways... You got to go easy... (patooiee! Damn it...) like I do. Course you probably think I'm crazy, but I'm not... (patooiee! Bingo!) I'm colorful... That's what happens when you live ten years alone in Bolivia - you get colorful..."

I looked out our bay window just after 7am. The remnants of last night's squall were long past and Lake Titicaca had returned to its peaceful blue self. While Susanne snoozed a few extra minutes I headed outside to the Cúpula's restaurant for some breakfast. Like much of the Cúpula the walls of the restaurant were made of large panes of glass. The morning sun shined brightly over my left shoulder as I wrote in my journal, sipping a café con leche. I hadn't had a decent cup of café con leche since we arrived in South America because the local milk was unpasteurized (and therefore not reliably safe.) The Cúpula restaurant, which prided itself on its hyper-hygienic conditions, served boiling hot coffee with pasteurized condensed milk. The syrupy milk quickly transformed the weak Bolivian coffee into a hot mocha milkshake.

Susanne joined me as our waiter brought out some fresh wheat bread and my fried egg. Susanne ordered a bowl of meusli, yogurt and fruit, something I probably wouldn't have dared ordered in any other restaurant on Lake Titicaca. The stereo system played a variety of folk guitar songs. I noticed one particular duet performed by two men that reminded me of a Simon and Garfunkel song - this must be Bolivia's answer to Peru's "El Condor Pasa," I thought. Perhaps I would hear 101 versions of it as well.

Susanne and I had both brought our journals and intended to write for a while after finishing breakfast. Not long after our waiter took away Susanne's empty meusli bowl I felt an acidic itch in my eyes.

"Do you feel that?" Susanne said simultaneously. "I think they burned something in the kitchen.

"Onions," I replied. "Onions and garlic. This is really getting uncomfortable." The morning chill made opening the windows a poor option so we packed up our things and returned to the room to sort out our plans for the day. Since we hoped to visit Isla del Sol tomorrow, today was our only full day to explore Copacabana. As it was we had already seen much of the town so we decided to start our morning with a climb of Cerro Calvario, the large hill immediately behind our hotel.

The two largest hills within Copacabana, Cerro Calvario (Calvary Hill) and Niño Calvario (Little Calvary), are strategically located just east of the town center. Both hills serve as an important pilgrimage site for the local faithful and offer an excellent vantage point of Lake Titicaca and the surroundings. Cerro Calvario in particular is home to a re-creation of the 14 stations of the cross recounting Jesus' last procession through Jerusalem. The current stations were added to the hill in the mid 1940s. Little Calvary, in contrast, plays host to much more ancient stations - stone monoliths erected by the Inca for astronomical observation. While Cusco and the Sacred Valley in Peru may have been the home of the Inca at the empire's peak, the Quechua creation myth traces the origin of the people to here along Lake Titicaca and Isla del Sol, just off the shore from the Copacabana peninsula. The ruins atop Little Cavalry are some of Bolivia's last tangible remnants to its Inca past.

Though most pilgrims and visitors climb the hills from their southern face, our hotel's location on the western slope gave us our own private base camp. Susanne and I began our hike by walking from the hotel along an unpaved road line by several small homes and sheep farms. An old man walking down the hill stopped just ahead of us, unlocking the gate to an adobe house. "Buenos días, señor," Susanne said to him. "Buenos días, mi señorita, buenos días," he replied. Soon after, two women in traditional Aymara dress passed us on the path. "Buenos días, señoras," I greeted them, but both campesinas looked straight and walked on without acknowledging my hello. "You know," I said to Susanne a moment or two later, "that's happened to me several times now. The older men of Copacabana are certainly friendly enough, but none of the women here would ever give us the time of day." "They're not comfortable with us," Susanne replied. "We're the ones intruding on their town, and they just aren't used to it." In all of our travels I had never encountered a place where the locals looked upon visitors with such icy disregard. I hoped we had simply crossed paths with just the wrong people - but what if all of Bolivia was like this?

dress passed us on the path. "Buenos días, señoras," I greeted them, but both campesinas looked straight and walked on without acknowledging my hello. "You know," I said to Susanne a moment or two later, "that's happened to me several times now. The older men of Copacabana are certainly friendly enough, but none of the women here would ever give us the time of day." "They're not comfortable with us," Susanne replied. "We're the ones intruding on their town, and they just aren't used to it." In all of our travels I had never encountered a place where the locals looked upon visitors with such icy disregard. I hoped we had simply crossed paths with just the wrong people - but what if all of Bolivia was like this?

Susanne and I made our way slowly up the side of the hill, taking regular breaks to catch our breath. "Think of this as cross-training for the hilly streets of La Paz," I said rather dryly. "And I thought we would have passed the worst of these hills at Machu Picchu," Susanne replied, gasping between words. Just ahead of us we could see the stony main path used by the pilgrims. We crossed over the dirt and loose stones in order to gain access to the path and the better traction it might offer. Four or five Bolivian families descended the path as we worked our way upward, with several others following not far behind us. I hadn't expected so many people climbing the hill today - perhaps Sunday mornings were an auspicious time to visit it.

After ten minutes of walking and pausing for air we reached a level platform that sat on a knoll between the two hills. The platform was a stone plaza, about 100 feet square, at the center of which stood a tall statue of Jesus. On the far side of the plaza, on the edge facing the lake, several families individually engaged in Aymara cha'lla rituals. Each family was attended by an old man serving as both priest and shaman. As is the case with many indigenous cultures of South America, the local Aymara indians adopted Spanish Catholicism and blended it with their own native traditions. On this particular occasion the cha'lla ceremonies appeared to serve multiple purposes, including the baptism of a baby, the confirmation of a young girl, and the blessing of a newlywed couple. On the far center of the plaza, the shaman placed a silver chalice of smoking incense on the ground, sprinkling ash into the four winds. He then lifted the chalice and held it to the foreheads of each member of the family, resting his other hand on the backs of their heads as the smoke enveloped them. The newlywed couple, meanwhile, held hands as the shaman shook a bottle of chicha and sprayed its contents onto the ground. Chicha, an indigenous Andean alcoholic homebrew, is now a popular carbonated beverage available in bottles; on many street corners in Copacabana I'd noticed families sitting around rusty cardtables consuming it, but this was the first time I had seen it used during a ritual.

rituals. Each family was attended by an old man serving as both priest and shaman. As is the case with many indigenous cultures of South America, the local Aymara indians adopted Spanish Catholicism and blended it with their own native traditions. On this particular occasion the cha'lla ceremonies appeared to serve multiple purposes, including the baptism of a baby, the confirmation of a young girl, and the blessing of a newlywed couple. On the far center of the plaza, the shaman placed a silver chalice of smoking incense on the ground, sprinkling ash into the four winds. He then lifted the chalice and held it to the foreheads of each member of the family, resting his other hand on the backs of their heads as the smoke enveloped them. The newlywed couple, meanwhile, held hands as the shaman shook a bottle of chicha and sprayed its contents onto the ground. Chicha, an indigenous Andean alcoholic homebrew, is now a popular carbonated beverage available in bottles; on many street corners in Copacabana I'd noticed families sitting around rusty cardtables consuming it, but this was the first time I had seen it used during a ritual.

Susanne and I paced the plaza, observing the ceremonies while doing our best not to intrude. Because of my telephoto lens I was able to snap some pictures without disturbing them, maintaining a respectable distance throughout our visit. On the far left of the plaza, just below Cerro Calvario's hillside, I spotted a pair of dark brown alpacas grazing in the grass. I took a quick picture with my telephoto before going over to investigate. An older gentleman with a large Polaroid camera sat behind the alpacas and smiled at us as we approached. "Cuanto cuesta para una photografa?" I asked. The man responded with an extended answer in Spanish which we both took as him explaining that he would photograph us with his camera if we wanted. I tried to explain to him we wanted to pay for pictures using our cameras, but he shook his head and raised his Polaroid. Meanwhile, Susanne petted the larger alpaca, stroking its thick brown hair. We could easily see the differences between alpacas and llamas now that we were up close. The alpacas were smaller with huge round eyes, almost like a cartoon character's, stubbier legs and thicker torso, not to mention its softer and longer wool. I again tried to offer the man money for a picture with our cameras but as I raised my camera at the alpaca he angrily spouted away in Spanish. Neither Susanne nor I had any interest in getting a Polaroid of us with the alpaca so we thanked him and retreated to the plaza, as he stared at us wondering why we wouldn't pay him to take our picture.

As we stepped away from the alpacas a thick spray of chicha splashed both of our jackets. A shaman had shaken a bottle for one of his ceremonies, spraying both of us in the process. I touched my finger to my jacket and tasted it - unfermented homebrew beer without the hops, I thought. Susanne turned to me and said "I think he did that on purpose." Perhaps she was right; we were the only gringos on the plaza, and for all we knew our welcome had worn thin. Neither of us wanted to make an issue of it so we decided to continue our climb up the big hill. We wound back and forth as we followed the steps to the top, passing the 12th and 13th stations of the cross. Visiting pilgrims had placed small stones on each station; the piles had grown so high I witnessed several landslides in miniature as people attempted to balance just one more stone on each monument.

|

Aymara campesina selling toys

for Cha'lla rituals |

As Susanne and I reached the top we could see the entire summit was paved with stone, both modern and ancient. A series of marble crosses peppered the length of the plateau, with groups of campesinas manning tableside shops along its left and right edges. At first the contents of each stall struck me as odd: toy trucks, doll houses, miniature plastic suitcases. Was this where locals would take their kids on the weekend to buy them toys? It then dawned on me that the toys were just props for cha'lla ceremonies: if you wanted to own a bigger house, you'd buy a plastic house and pray for it. If you wanted a new car, you could choose the miniature hatchback, pickup truck or sedan of your dreams. All the great material things in life were here for the asking.

Susanne and I walked to the far end of the summit. More stone steps descended to near the water's edge, but we sat down on the plateau and quietly observed the action around us. Another shaman attended to an elderly couple that had purchased a toy van. The shaman extinguished a candle and opened a large bottle of chicha, sharing its contents with the couple. The wife lifted her glass into the air, then spilled some chicha on the soil by her feet - an offering of the first sip to the earth goddess Pachamama. Susanne and I desperately wanted to take a picture of the ceremony and tried to think of a tasteful way to do it. We were too close, too obvious to get away with any photo without being extremely rude, so we kept our cameras at our side, choosing not to make a scene.

As we watched the ceremony and enjoyed the view of the lakeshore, a man in his late 40s came up to us and said "Buenos días amigos." I didn't know if he was just being friendly or trying to sell us something as he started to speak quickly in Spanish. He read the confusion on our faces and finally asked, "Habla Español?"

"Un poquito," Susanne and I replied, both self-conscious of our ignorance.

|

| Summit of Cerro Calvario, Copacabana |

"He wants to know if you know there are stairs going down the other side," we heard a young American voice speak. An Hispanic teenage girl in jeans and a t-shirt stood to our left, staring at us with a quintessentially teenage "Jeez, don't you know anything?" look on her face. Her parents and younger brother then appeared, having overheard what she said.

"Are you from the US?" the mother asked us in English.

"Yes, we're visiting from Washington DC."

"We're practically neighbors!" she replied. "We're visiting from Alexandria." Yet another small-world experience.

"Wow, I actually live in Arlington," I replied, "so we really are neighbors.

"Our son was born in Arlington, " she said, pointing to her obviously embarrassed boy. "Very small world."

"Do you know what they are doing?" the husband said to me quietly, pointing to the elderly couple with the shaman.

"It's some kind of cha'lla ceremony, right?" I responded.

"Yes, they're asking for the things they want to receive one year from now."

"I didn't realize the ceremony had a specific time frame attached to it," I replied, interested in his Bolivian-American perspective.

"Well, they're not asking for these things to appear out of nowhere next year," he explained. "It's more like setting a goal: over the next year I will work hard for something. This is what I want to work for."

The daughter and son then tugged at their mother's shirt, apparently wanting to explore the other side of the summit. "I hope you enjoy Bolivia," their parents said to us, smiling.

"See you on the Metro someday," I replied.

Susanne and I briefly posed for some photos before beginning our climb down the hill. A young girl appeared from behind one of the stations and smiled at us. I smiled back and pointed to my camera, hoping I could get her to agree to a picture. She giggled and darted behind the station. I slyly followed her and surprised her on the other side. Again she laughed and ran to the opposite end, biting a fingernail as she waited for me to catch up. Once I got back to the other side, though, she vanished. I guess I wasn't fast enough for her.

|

| Church minibus recently blessed during a cha'lla ceremony |

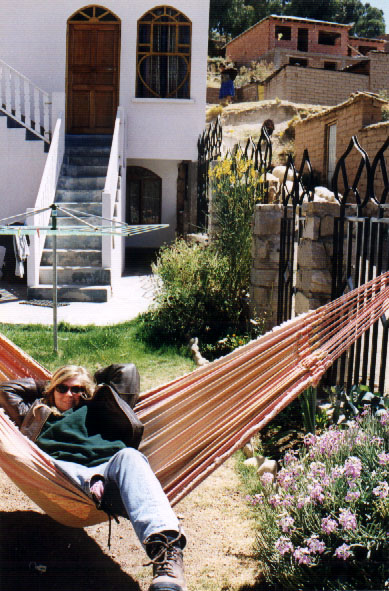

I was interested in climbing the other hill to visit the Incan monoliths but Susanne was eager to return to town, having had more then enough climbing for the day. At the bottom of the hill we passed a small chapel, deserted save a minibus decorated in flower garlands. I suddenly remembered there might be more cha'lla ceremonies going on by the cathedral. Saturday was usually the big day for locals to have their vehicles blessed, but I figured some might just as easily save it for Sunday as well. Susanne and I were both in need of a drink, though, so we stopped at the Solar Café for a coke and a mate. The small garden café was empty of patrons, so we asked a waiter if the restaurant was open. "Sí, por favor," he replied, pointing to an available table.

Susanne and I sat down, pulling our journals from our backpacks. I noticed the strong scent of fresh dill in the air; behind me a large dill plant swayed in the breeze. "Now if only they could put some of that dill on the local trout, then they'd have a big hit on their hands," I said to Susanne. The waiter quickly stepped out of the kitchen and dropped a small bowl of sourdough bread on our table. "Uno maté de coca y una Coca Cola, por favor," I asked. After disappearing in the kitchen for a few minutes, the waiter reappeared with two large bowls of steaming hot soup. Susanne and I looked at each other, perplexed. "No sopa, señor," I said. "Coca Cola y maté de coca solamente." The waiter stared at us for a moment, then shook his head in annoyance before walking back into the kitchen with the soups.

"Did he just assume we were ordering the set-menu lunch?" I asked.

"Looks like it," Susanne agreed.

Our drinks hadn't arrived yet and I was tempted for us to leave the restaurant. As it was, though, we had already started to munch on the sourdough bread - bread that was probably intended for the soup we never ordered. Susanne wasn't overly concerned about the incident and insisted we stay for our drinks, which arrived a few minutes later. "We at least have to pay for this bread," I said. "I think this guy is ticked off enough as it is."

We sat there in the garden and did our best to enjoy our drinks as if nothing had happened. Each time the waiter subsequently passed us he made an effort to not look over at us. "This is crazy," I said. "Let's just pay and get out of here. We can try again somewhere else."

"What's the big deal?" Susanne replied; she was intent on finishing her Coke. Our original plan had been to write in our journals for a while but the awkward tension with the waiter killed my concentration. I sat back and smelled the fresh dill, observing an eyelash floating in my mate.

About ten minutes later a group of eight German tourists sat down next to us, ordering the set-menu lunch and a round of Pacena beers. Our quiet garden transformed into a brauhaus as the Germans had a merry time drinking and reading aloud sections from their Lonely Planet Bolivia book. "Okay, I guess we can go now," Susanne said. I managed to request the check from another waiter who had missed the entire soup incident. But then the first waiter returned, bill in hand. There was no mention of the bread on the bill.

"El, pan, señor," I said. "Cuanto cuesta?"

"No, señor," he shook his head shyly, clearly embarrassed about the whole thing.

"Por favor," I insisted. "Cuanto cuesta?"

"Ok, uno boliviano," he responded - about 18 cents. I paid the bill and threw in an extra four bolivianos before exiting through the garden café gate.

A block south of the Café Solar we found another restaurant I believe was called the Inka Wasi. Its garden was crowded with diners so we found two seats on the inside, which was decorated with dark wood paneling and Aymara handicrafts. A waitress brought out two large bowls of sizzling soup and (thankfully) brought them to the table behind us. Perhaps the set-menu almuerzo wasn't a bad idea after all - and at 10 bolivianos for a soup, entree, fruit and coffee you couldn't beat it. Susanne ordered an omelette while I requested the almuerzo, despite having no idea what was included in the lunch. A waiter soon returned with my own bowl of hot soup - peanut soup with corn and quinoa. I had heard about Bolivian peanut soup but didn't know exactly what it would be like. I had expected it to be a thick, creamy soup - perhaps peanut butter sandwiches of yore clouded my expectations - but instead I received a light vegetable soup seasoned with ground nuts and grains. The soup was pleasantly refreshing, and it went especially well with the spongy squares of bread served on the side.

Not long after Susanne received her omelette the waiter unveiled my surprise main course, a cold potato salad with peanut sauce, sliced cheeses, olives and onions. I was a little hesitant at first to eat a cold salad in Bolivia but from the nature of the cooked potato and sauce I chose to assume that the meal was well heated before being thoroughly chilled. Just in case I swallowed four Pepto Bismol pills in order to coat my stomach with a pre-emptive strike of medicine. The salad itself was strange to my tastebuds: the cold, peeled potatoes were generously coated in a peanut sauce with a consistency a little thicker than Thai satay sauce. The cheeses, onions and olives were rather straightforward but the overall combination of flavors worked well. "It's pretty good," I said to Susanne. "Wanna taste it?"

"Forget it," she replied, digging into her omelette.

|

| Bolivians getting their truck blessed at Copacabana cathedral |

Having wrapped up lunch Susanne and I walked the two blocks uphill to reach the Copacabana Cathedral. As expected we found the plaza in front of the cathedral crowded with large groups of Bolivians

getting their cars blessed. On the far left of the cathedral a bus crowded with talkative travelers was anointed with flowers on its hood and around its front lights. A group of young men standing around a red pickup truck poured beer over its warm engine, causing jets of steam to rise in the air. Two girls and a boy remained impatiently in the bed of another truck as their parents waited for an old man to read prayers to them. Throughout the ceremonies other cars that had been previously blessed drove by slowly, honking their horns and waving like a bunch of fraternity brothers arriving at a campus tailgate party.

The whole scene around the cathedral had a festive atmosphere but there was a palpable tension between the traditionally dressed campesina women and the small groups of gringo tourists, including ourselves. The campesinas of Lake Titicaca are well known for their discomfort with visitors; many of the women refuse to be photographed while others demand large sums to have their pictures taken. Meanwhile, several tourists including myself had large zoom lens mounted on their cameras which allowed us to capture pictures at a greater distance. I took a handful of pictures early on in our visit but became much more uncomfortable with the situation after pausing to watch the events around me. A pair of European men with huge telephoto lens stood behind a telephone pole, sizing up their targets before shooting. Another man used the hit-and-run tactic, getting shots of angry campesinas up close and walking away swiftly, gambling that the women wouldn't go after him. His method gave "drive-by shooting" a whole new meaning.

dress passed us on the path. "Buenos días, señoras," I greeted them, but both campesinas looked straight and walked on without acknowledging my hello. "You know," I said to Susanne a moment or two later, "that's happened to me several times now. The older men of Copacabana are certainly friendly enough, but none of the women here would ever give us the time of day." "They're not comfortable with us," Susanne replied. "We're the ones intruding on their town, and they just aren't used to it." In all of our travels I had never encountered a place where the locals looked upon visitors with such icy disregard. I hoped we had simply crossed paths with just the wrong people - but what if all of Bolivia was like this?

dress passed us on the path. "Buenos días, señoras," I greeted them, but both campesinas looked straight and walked on without acknowledging my hello. "You know," I said to Susanne a moment or two later, "that's happened to me several times now. The older men of Copacabana are certainly friendly enough, but none of the women here would ever give us the time of day." "They're not comfortable with us," Susanne replied. "We're the ones intruding on their town, and they just aren't used to it." In all of our travels I had never encountered a place where the locals looked upon visitors with such icy disregard. I hoped we had simply crossed paths with just the wrong people - but what if all of Bolivia was like this? rituals. Each family was attended by an old man serving as both priest and shaman. As is the case with many indigenous cultures of South America, the local Aymara indians adopted Spanish Catholicism and blended it with their own native traditions. On this particular occasion the cha'lla ceremonies appeared to serve multiple purposes, including the baptism of a baby, the confirmation of a young girl, and the blessing of a newlywed couple. On the far center of the plaza, the shaman placed a silver chalice of smoking incense on the ground, sprinkling ash into the four winds. He then lifted the chalice and held it to the foreheads of each member of the family, resting his other hand on the backs of their heads as the smoke enveloped them. The newlywed couple, meanwhile, held hands as the shaman shook a bottle of chicha and sprayed its contents onto the ground. Chicha, an indigenous Andean alcoholic homebrew, is now a popular carbonated beverage available in bottles; on many street corners in Copacabana I'd noticed families sitting around rusty cardtables consuming it, but this was the first time I had seen it used during a ritual.

rituals. Each family was attended by an old man serving as both priest and shaman. As is the case with many indigenous cultures of South America, the local Aymara indians adopted Spanish Catholicism and blended it with their own native traditions. On this particular occasion the cha'lla ceremonies appeared to serve multiple purposes, including the baptism of a baby, the confirmation of a young girl, and the blessing of a newlywed couple. On the far center of the plaza, the shaman placed a silver chalice of smoking incense on the ground, sprinkling ash into the four winds. He then lifted the chalice and held it to the foreheads of each member of the family, resting his other hand on the backs of their heads as the smoke enveloped them. The newlywed couple, meanwhile, held hands as the shaman shook a bottle of chicha and sprayed its contents onto the ground. Chicha, an indigenous Andean alcoholic homebrew, is now a popular carbonated beverage available in bottles; on many street corners in Copacabana I'd noticed families sitting around rusty cardtables consuming it, but this was the first time I had seen it used during a ritual.