|

| Copacabana and Lake Titicaca |

|

|

|

Sundance: What's your idea this time?

Butch: Bolivia.

Sundance: What's Bolivia?

Butch: Bolivia. That's a country, stupid.... In Central or South America, one or the other.

Sundance: Why don't we just go to Mexico instead?

Butch: 'Cause all they got in Mexico is sweat and there's too much of that here. Look, if we'd been in business during the California Gold Rush, where would we have gone? California - right?

Sundance: Right.

Butch: So when I say Bolivia, you just think California. You wouldn't

believe what they're finding in the ground down there. They're just fallin' into it. Silver mines, gold mines, tin mines, payrolls so heavy we'd strain ourselves stealin' 'em.

Sundance: (chuckling) You just keep thinkin', Butch - that's what you're good at.

Butch: Boy, I got vision, and the rest of the world wears bifocals....

With 11 hours of sleep under our belts, Susanne and I had a quick breakfast of maté de coca, rolls and jam in the Hostal Zurit dining room. We returned to our room just after 7:30am to make sure all of our belongings were packed up for the bus ride to Copacabana. We had only been in Peru for a week, but it was now time to go to Bolivia. When Susanne first suggested we visit Peru and Machu Picchu, I immediately replied that we should also spend a few days in Bolivia.

Granted, while Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid came to Bolivia with dreams of banks overflowing with gold and silver, our only motivation was a taste for some adventure. Bolivia is the most isolated country in South America, and also its highest - at over 4000m, the capital city of La Paz is the highest capital in the world (even Lhasa, Tibet is lower: 3650m). Bolivia is home to half of Lake Titicaca, as well as the ancient ruins of Tiwanaku and the Spanish colonial capital of La Paz. The days of Butch and Sundance robbing silver mines may be gone, but Bolivia still conveys a frontier-like mystique that continues to attract intrepid travelers from around the world. Why go to Bolivia? How could we not go to Bolivia when we're this close? (and besides, how often do you get a chance to say, "Let's go to Bolivia today?")

About 7:45am Zacharias showed up at our door, a little ahead of schedule. "Are you ready?" he asked. "Is it 8 o'clock yet?" I responded, shoving the last bits of clothes into my backpack. "Perhaps my watch is a little fast," he said. No matter, I'd rather have our guide be a little early than a little late. We hopped into his minibus for a quick ride to his tour agency, where we waited inside for the Puno to Copacabana bus to arrive. "Here is your ticket," Zacharias said as he handed me a flimsy pink slip not much thicker than toilet paper. "The ticket is good to La Paz," he continued, "so when you are ready to leave Copacabana, go to Vicuña tours and they will reserve a seat for you on the La Paz bus."

I was more than a little surprised when Zacharias said our tickets would be good beyond Copacabana. Our ten dollars would get us from Puno all the way to the Bolivian capital on a spacious tourist bus - not bad. A few minutes later a large bus pulled in front of the agency. "This is your bus," Zacharias pointed. "If you want, look for me at the Hotel 6th de Agosto. Have a good trip." With that, Zacharias shook my hand and returned to his office.

Susanne and I boarded the bus, which was already crowded with travelers. "Asientos tres y quatro," the bus agent said, pointed to a row of seats on the right side of the bus. We settled into our seats, Susanne's backpack crammed above her head, mine in between my legs. Most passengers stowed their luggage on the top of the bus, but such stowage has always made me uncomfortable, especially over poorly paved roads with lots of large bumps and potholes. By 8:30 the bus was on its way. The driver pulled out a small box of cassette tapes and plugged one of them into the stereo system. Loud Cuban salsa music filled the air - an old recording of "Bamboleo":

Bamboleo, bambolea,

Porque mi vida yo la prefiero vivir asi...

"Havana's greatest hits, 1957," I said to Susanne. "What could be better for a dusty bus ride to Bolivia?"

For the first few miles of the drive we paralleled the coast of Titicaca, the sun rising higher above the cobalt blue waters. By 9am, though, the bus veered inland, continuing along the paved highway to Yunguyo, the Peruvian border crossing to Bolivia. We drove quietly for the next 90 minutes, cruising through rocky hill country and farmland to the romantic sounds of "Guantanamera." Our bus needed a dance floor.

Just before 10am we pulled into Yunguyo and stopped in front of a casa de cambio. "Change your money here," the bus agent told us. We only had about $25 in Peruvian soles at this point, so I cashed these in for bolivianos while Susanne did the same with a traveler's cheque. "Is this rate good?" she asked me, handing me a calculator with the number "5.45" on it. "Pretty good," I said. "Just be sure to say 'No tiene sencillo?' if they give you too many bills larger than a twenty." Bolivia was notorious for its national obsession with small change - no one ever seems to have anything large than a 10- or 20 boliviano note (about two and four dollars) except to pay large bills. I dreaded the thought of not being able to buy food or water anywhere because no one would have change for a 50 boliviano note. Nevertheless, the woman behind the counter tried to give us our change back in 100 boliviano notes. "Sencillo, por favor," I asked. "Veinte, diez notas?" "I will give you 50 notes," she said in English. "You will have no problem with them." I guess we'd find out one way or another since she seemed to be in no mood to give up her small change either.

Back on the bus we drove for another five minutes before reaching a small hill. The road up the hill was surrounded on both sides by groups of campesinas peddling bags of peanuts, popcorn, sodas and small change Bolivianos. The 30 or so of us on the bus climbed outside and gathered behind a long queue of people extending from an immigration office. "Hopefully this entire process will take less than an hour on both sides," I said. Susanne looked at me skeptically. The group waited as the line slowly progressed. Some people took advantage of one sole shoeshines from local boys. Several of them pestered us for a shine, and I couldn't figure out how to explain to them that my hiking boots weren't leather. Susanne, on the other hand, had no good excuse - her Rockports were coated with dust from our days in Cusco and Machu Picchu. "I can wait a little longer. No, gracias," she'd say to the young entrepreneurs, no matter how hard they pressed.

We eventually made our way to near the front of the line. Susanne and I entered a small office where two immigration officers sat at their desks. The officer looked me over and flipped through my passport, trying to find the entry stamp I had received in Lima. With the press of a black stamp he closed out my stay in Peru and sent me outside. Susanne followed a moment or two later. We were well ahead of most of our fellow bus-goers, who were still in the queue. One of them, a lanky Spanish man with matted dreadlocks, stood in line with a smouldering cigarette in one hand and a liter bottle of Arequipeña beer in the other. "Now that's one hell of an exit," I said to Susanne, though I can't say I'd ever try it myself.

The bus agent was nowhere to be seen so I didn't have a solid idea what to do next. "I think we just walk across the border now," Susanne suggested. A Swiss woman from our bus was waiting for someone and we asked her what she thought we were supposed to do. "Go that way, I think," she said, pointed to the adobe gate on the top of the hill. "I guess we better go to Bolivia, then," I said.

|

| Crossing the border from Peru into Bolivia |

The Peru-Bolivian border was the most casual border I've ever crossed. There were no police or border guards at the gate; only more campesinas lining both sides of the crossing with their blankets stacked with peanuts and boliviano coins. There were no official signs saying "entrada," "salida" or even "Bienvenidos a Bolivia!" As far as we could tell we were simply passing under a vaulted gate. "I guess that was it," I said as we crossed through to the other side of the hill. Indeed, we were now in Kasani, Bolivia. Near the bottom of the hill we reached another building with yet another immigration office. As we stood in line we were handed some paperwork to fill out, which we completed by the time we reached an older man behind a large desk. He gave each of us a stern look, taking our passports and papers in one swipe. I pictured Michael Palin playing a stodgy old bureaucrat in some Monty Python border crossing skit: "Ohh... I'm sorry guv'nah, you can't come 'eere; You don't know tha bloody password..." The man looked at each line on our papers, giving each a large check mark of approval. Having completed the forms to his satisfaction, we were then pointed to another office where a sleepy official stamped our passports after counting the number of check marks on our paperwork. Susanne and I were now officially sanctioned to spend the next 30 days in Bolivia as we pleased, even though we actually had only a week available to us.

Our bus was now parked a few dozen yards from the Bolivian immigration office. No one was on board yet so I decided to visit a small market at the bottom of the hill. "Try to find some crackers or vanilla wafers," Susanne said. Crackers and wafers, it seemed, had become the staple of our diets along the Altiplano so I searched for a campesino selling roasted peanuts in order to give us some variety. Copacabana, apparently, is known for its giant peanuts, rivaling any nuts coming out of Jimmy Carter's farm in Georgia. I soon discovered, though, that most of the market stalls offered heartier sustenance: huge bowls of quinoa soup, loaves of bread, even skewered beef hearts grilling over charcoal pits. Eventually I found a campesina with a lofty heap of peanuts piled atop a red and black wool blanket. "Cuanto cuesta?" I asked, pointed at the shells. "Dos bolivianos," she replied. I wasn't sure how many peanuts 40 cents would get me, but she soon handed me a plastic bag with half a kilo of freshly roasted peanuts, more than enough to keep us busy for the rest of the ride.

After scrounging another bottle of agua sin gas and Susanne's cookies I returned to the bus, where Susanne was sitting outside. I started to get comfortable on a large rock, cracking open a few peanut shells, but the bus driver and his partner quickly returned, clapping their hands to get everyone back on the bus. Within a minute or two after boarding we then hit the road again. Numerous seats that were once filled with passengers were now empty. "I hope they're not leaving anyone behind," Susanne said.

As we continued onward the smell of the warm roasted peanuts began to drive me crazy. I didn't have a bag in which to put the spent shells so I improvised by cracking the window and tossing them outside. It was a futile effort; the wind blew the shells back into the bus each time. I then poured a small pile of nuts into my lap. "I guess we'll just have to use the peanut bag for the shells as well."

Just before noon our bus descended into a rocky valley, revealing Lake Titicaca once again to our left. As we entered Copacabana our bus was stopped by a man in a uniform who informed us in Spanish and English we each had to pay a one boliviano tax "for the upkeep and preservation of Copacabana." Our Lonely Planet book had warned us of this scam; basically we would be bribing the police to visit the city. There wasn't much we could do, though, since they weren't going to let us go anywhere without paying. I handed the man a five boliviano coin and said, "Dos personas." He handed us two slips of paper and two coins. Two bolivianos? We should be getting three back. Susanne and I both exclaimed, "Señor, tres bolivianos, por favor." Neither of us were very pleased. The man looked at the two coins in my hand and flipped them over. "Sí, tres bolivianos," he said before climbing off the bus. Apparently one of the one boliviano coins was actually a two boliviano coin, the only difference between the two being a zigzag edge on the inside ring of the two boliviano coin. Woops.

The bus pulled into the heart of Copacabana, along Avenida 6th de Agosto (every major street in Bolivia, I later concluded, is an auspicious occasion). The unpaved road sloped quickly down to Lake Titicaca, about 100 yards ahead of us. Going uphill was Copacabana's main square, and above that, its Moorish cathedral. Beyond that, there wasn't much else here. Copacabana is a small city by most standards, easily accessible on foot as long as you don't fall into its many potholes or open sewers.

We didn't have reservations in town but Zacharias had suggested we try the Hotel 6th de Agosto, which he promised was right along the heart of Avenida 6th de Agosto. To our surprise, though, none of the locals had ever heard of it. "Hotel 6th de Agosto?" they repeated. "No Hotel 6th de Agosto aquí." We were only a few blocks away from the highly recommended Hostal Prefectural, recently renovated and renamed the much more marketable Hotel Copacabana. The hotel was a massive orange building just above the lake, with a spacious foyer, lobby and café inside. Unfortunately, they were full booked for the weekend. Susanne took advantage of their restrooms while I asked the hotel manager for any suggestions. At first he said the Hotel Ambassador was nice, but the Lonely Planet described it as "the acting youth hostel in Copacabana," not exactly what we had in mind. I pulled out our map and showed it to the manager, hoping he might offer more suggestions. "Hotel Cúpula," he said, pointing to a spot on the map where there was no hotel listed. "Muy tranquilo." "Cuanto cuesta para un doble con bano privado?" I asked. "Setenta Bolivianos, cién, ciénto veinte bolivianos, muy bueno..." That was still less than $30 a night so we decided to check it out.

|

| Hotel Cúpula, Copacabana |

We hauled our packs down the road past Avenida 6th de Agosto and up an unpaved segment of Avenida 16th de Julio, sloping up a large hill. I was reminded just how high the local altitude was as we quickly lost our breath climbing each step up the hill. At a deserted intersection I saw a small blue sign with the words "Hostal Cúpula" above an arrow pointing left down Avenida Perez. We walked along the side of the hill, revealing a stunning view of Lake Titicaca and the city below. A man in a police uniform stood by a wrought iron gate and waved us in, smiling. The Hostal Cúpula, freshly whitewashed with gardens of blooming flowers, was a small Eden perched above Copacabana. Its roofs were decorated with large Moorish onion domes more at home along the Mediterranean than in chilly Bolivia. In its tiled courtyard a young man with long blond hair sat on a marble bench, strumming a guitar as two companions leaned back and listened. There had to be a mistake - what on earth was this place doing in Copacabana? (and perhaps more importantly, why wasn't it in any of the tour books?) I rang the bell at the front desk; a short Bolivian man descended a white staircase and welcomed us. "May I help you?" he said in English. "Tiene un doble con bano privado?" I asked. "Yes, yes," he said. "Cién bolivianos." 100 bolivianos was just under $20, just right for our budget and a welcomed break from the inflated prices of Cusco and Aguas Calientes. He brought us to a bright, sunny room with a view of a courtyard garden. There were three beds inside, a bathroom with hot water, a large desk with chairs and original oil paintings on the wall. Classy accommodations indeed.

We dropped our backpacks on the bed and immediately headed for the two vacant hammocks suspended in the garden. While the weather was chilly, the bright Altiplano sun warmed our spirits as we crashed into the canvas hammocks and sighed. "I think I can spend a few days here," I said. We in fact had only two nights in Copacabana; on Monday we planned to spend a night on Isla del Sol, a two-hour boat ride from town on Lake Titicaca. The next morning we would return to Copacabana and catch an early afternoon bus to La Paz. A day and a half should be more than enough time to see the local sights.

After relaxing in the hammock for a while Susanne and I grabbed our cameras and walked down into town. We needed to get something to snack on and tie us over until dinner, but first I suggested we visit the cathedral, Copacabana's main attraction. As we walked through town we were passed by several cars and trucks decorated with garlands of flowers. Each Saturday and Sunday morning, hundreds of people would gather in front of the cathedral to perform cha'lla ceremonies, ancient Aymara blessings that blended indigenous beliefs with Catholicism. If you bought a new car or were beginning a trip it was important to perform cha'lla on your car. It was now well into Saturday afternoon so by the time we reached the cathedral plaza things had returned to normal. Campesinas lined the sidewalk with souvenir stalls specializing in small reed boats, religious icons, weavings and stuffed seagulls.

blessings that blended indigenous beliefs with Catholicism. If you bought a new car or were beginning a trip it was important to perform cha'lla on your car. It was now well into Saturday afternoon so by the time we reached the cathedral plaza things had returned to normal. Campesinas lined the sidewalk with souvenir stalls specializing in small reed boats, religious icons, weavings and stuffed seagulls.

|

| Copacabana Cathedral |

|

| Blind violinist, Copacabana |

Inside the cathedral's grandiose white gates was another plaza dotted with beggars. As we walked the plaza towards the cathedral, old campesina women held out small empty bowls, chanting "Señor, por favor, por favor..." We had been told to expect a lot of beggars in Bolivia; fellow travelers always seemed to stress the poverty here. I was saddened to see the Aymara women begging but knew there was little I could do about it. Susanne noticed a blind man playing an old violin on the cathedral steps. I gave her two bolivianos to put in his cup. She dropped the coins in his cup and took a picture; the old man smiled and began to play.

The inside of the cathedral was small and modest, yet peaceful; we sat for a while as I quietly read my guidebook's history of the church. The cathedral was best known for a statue of Mary visited by thousands of pilgrims each year. The museum housing the statue wasn't open today so after a few minutes of solitude we returned to the outer plaza. I approached a campesina selling reed boats and motioned to my camera to see if I could take a picture. "Quatro bolivianos," she hissed at me. Four bolivianos? I must have looked shocked because she quickly reduced the price to two bolivianos, which I handed over to her. She sat there impatiently, staring over my shoulder as took my picture. "Muchos gracias, señora," I said, which she totally ignored, spitting some coca leaves to the ground. I had been warned that the people of Lake Titicaca were known for their abruptness but I was still taken aback by her chilly reception. Indeed, as we walked down Avenida 6th de Agosto towards the lake I noticed none of the local women would look at me as they passed by, even if I said "Buenos tardes." There was a tension in Copacabana I hadn't expected; hopefully it wouldn't permeate our entire visit.

About halfway down the avenida Susanne and I discovered a hole-in-the-wall café called Inti Huayri. The café seated no more than eight people: two pairs on small stools made of tree stumps, and three or four people on a broad reed boat that had been converted into a sofa. A young couple sat on the boat/sofa, whispering sweet nothings to each other as they drank their coffees. Susanne and I both ordered maté de cocas and some fresh bread, along with an empanada con queso for myself. A teenage girl brought us our snacks then returned to her spot behind the counter, where she fiddled with the radio into she found the right song. Susanne and I sipped our matés watching children play on the street outside. The winds had picked significantly since we sat down; the girl behind the counter twice had to step out and prop up the menu sign which kept blowing over in the gusts. Thick swirls of dust rolled down the avenida with each gust of air. Several groups of young men in uniforms walked by - military cadets, perhaps. In the other direction I spotted younger children wearing white lab coats, probably coming from school. "This town sure does have a lot of young pharmacists," Susanne said.

A tall young man with a thin goatee entered the café and sat across from the couple on the reed couch. He spoke quickly in Spanish though I noticed he occasionally threw in some French phrases. Susanne and I continued to snack until the goateed man pointed to Susanne and said, "You have my camera." I didn't know what he meant at first but then saw he was holding an old Canon AE-1, not unlike Susanne's. "They're great cameras, aren't they?" Susanne said. "Mine is over 18 years old and it's still great."

"I think my battery is dead," he replied. "The camera will not work. Do you know where the batteries are held? I have never replaced it before." Susanne and the man fidgeted with his camera until she found the battery compartment. "Six volts," she said as she looked at his dead battery. Poor guy, I thought. Where would he find a six volt camera battery for a 20-year-old camera in Copacabana?

"Actually, I saw a woman by the cathedral selling nothing but batteries," Susanne said. "You may want to go up the street and see what she has." "Sí, sí, sí, I think I will do that," he replied, his stuttering shyness overcome by a broad smile. "Are you from the United States?" he continued. "We are from France, but we live in Peru."

"Are you in school?" I asked.

"Sí, sí, in Lima," he replied. "We have come to Bolivia on, on..."

"Vacation," his friend jumped in. "We will also go to La Paz before returning to Lima."

"I think I'll go look for my battery," the goateed man continued. His two friends swallowed their last sips of coffee and grabbed their cameras. "I hope you enjoy Bolivia," he said. "Bonne chance," I replied, pointing to his camera as they stepped out the door into Copacabana's windblown streets.

|

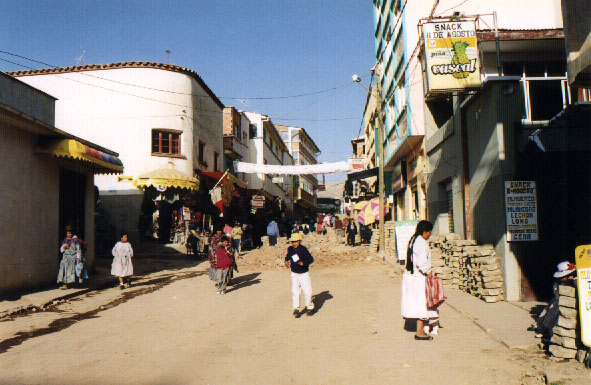

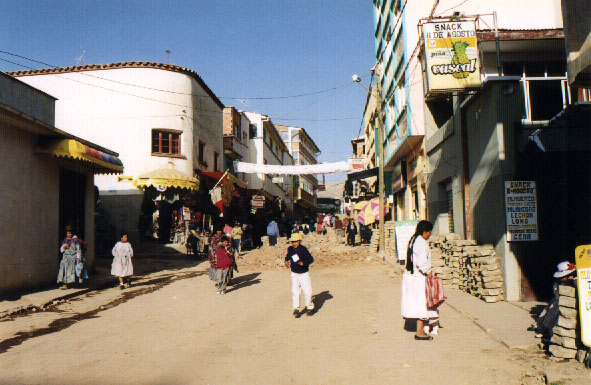

| Avenida 6th de Agosto, Copacabana |

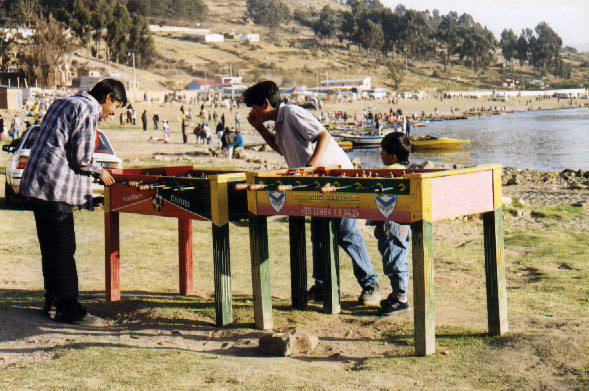

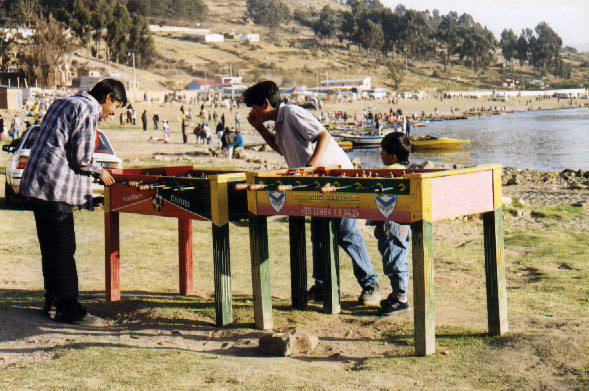

After a refill of matés, Susanne and I left the café and continued down 6th de Agosto towards the lake. Much of the avenida was a complete mess with open sewer lines and exposed pipes creating a continuous obstacle course. Earth-moving equipment sat idle beyond an intersection - I wondered if the streets were always like this or if the local workers had taken the weekend off. The avenida descended as we approached the lakefront. The local shops displayed a variety of junk food, snacks and drinks on tables outside their windows - last minute supplies for gringos trekking to Isla del Sol, I surmised. As we reached the lake Copacabana came to life, with hundreds of people gathered on the beach with their friends and families. On one stretch of sand were several rows of new cars draped in flowers, their owners standing around their hoods celebrating over large bottles of beer. Four boys monopolized two large foozball tables sitting in the middle of the beach while two younger kids horsed around in the sand, wrestling back and forth.

|

| Foozball players, Lake Titicaca |

About a dozen or so boats waited along the shore, their owners plying the beach for prospective customers. "Señor, señor," one of the boatman began to say to me as he motioned proudly to his motorless rowboat. "No gracias," we responded, continuing our stroll along the beach. I didn't spot many fellow gringos by the lake; most of the visitors appeared to be either locals or Bolivian tourists in town for a pleasant weekend. Further down the beach we found a small amusement park consisting of a carousel and pony rides. I didn't know what to expect before coming to Copacabana but I could now see how this small town had earned its reputation as a lazy beachside resort. There wasn't much to do here, and that's probably just the way everyone liked it.

|

| Lake Titicaca sunset |

As the sun drifted down the sky towards the shimmering lake Susanne and I agreed we should find a place to get dinner. We were a block below the Hotel Copacabana so we turned uphill to check out its restaurant. For a hotel that was supposedly full booked the Copacabana was eerily quiet, with no guests to speak of in the atrium café. The hotel staff informed us that dinner service wouldn't begin until 7:30pm so we decided to spend the next two hours relaxing over some drinks and our journals. We quietly sipped our matés and Fanta as we made a feeble attempt to catch up in our writing. Usually we're pretty good about keeping our travel journals up to date; though we might sometimes fall behind by a day or two, we rarely get significantly behind. For whatever reason, though, South America seemed to either eat up our free time or make it as inhospitable to writing as possible, whether it was an exhausting day at Machu Picchu or a nerve-wracking train ride across the Altiplano. I dearly hoped Copacabana would give us the chance to catch up and not fall perilously behind; today, at least, we seemed to be off to a pretty good start.

Around 7:30 the restaurant maitre d' invited us into the main dining room, handing us the list of tonight's specials and the a la carte menu. Their dinner special consisted of a fish called pejerrey - we didn't know what the English equivalent would be. I for one was eager to try the local specialty - trucha criolla, or salmon trout. Fortysomething years ago a World Health Organization representative explored methods to improve the meagre diets of the local Aymara population. Someone came up with the brilliant idea of seeding Lake Titicaca with fresh-water trout. They imported salmon trout, dumped some in the lake, and overnight, a new fishing industry was born. At two or three dollars for an entire fish platter you couldn't beat it, especially when compared to the tired Altiplano alternatives of salted beef, french fries and egg sandwiches.

I ordered a trout sauteed in white wine sauce while Susanne chose the chicken dish. My wine sauce was described as con zanahorias; unfortunately zanahorias wasn't in our dictionary's food and beverage guide. I tried to ask the waiter if he could explain what it was but he couldn't find the words for it. "Imagine trying to answer the question 'What is an eggplant?' to someone who doesn't speak English," I said to Susanne after he left. As we waited for our meals we both sipped fresh cups of maté de coca as the television in the main lobby played old music videos. "Come on, come on, come on now touch me babe/ Can't you see that I am not afraid," Jim Morrison of the Doors sang as the light from the television flickered on the glass windows overlooking a darkened Lake Titicaca. Far in the distance over the lake I noticed fantastic lightning strikes penetrating the blackness, growing stronger and closer every several minutes.

"Wonderful," I said, "a severe thunderstorm and we don't even have umbrellas. I hope the food gets here soon."

"Relax," Susanne replied. "We can always take a cab.... They have cabs here, right?"

As far as we knew the local taxis were more than just long distance shuttles between here and the border. Hopefully there would be no problem catching one at night, though I honestly didn't know if the walk back to the Hostal Cúpula was completely passable by car. If the storm took its time we'd probably be all right.

As I dwelled on impending showers the waiter delivered our entrees. Despite being fried and served with more french fries, the salmon trout was tasty and hot, sitting on a bed of rice and pureed carrots - zanahorias, apparently. Susanne's chicken was nothing to write home about, and her cold, greasy rice pilaf set off numerous gastrointestinal alarms in both of our minds. "I think that great chicken you had in Puno was an aberration," I said. "You may be stuck with greasy dark meat chicken for the rest of the Bolivia."

After using every available napkin to wipe the oils of our fingertips Susanne and I agreed it was time to get out of here before the storm broke. Our waiter was kind enough to cash a 100 Boliviano note - just under $20 but still rarely tolerated in Bolivia outside of hotels and ritzy restaurants. We struggled over whether or not to leave a tip: our travel guide emphasized that tipping is extremely rare in Bolivia unless you're at the finest dining establishment or received service that went well beyond the call of duty. "Leave something," Susanne insisted. While I liked the idea of traveling in a land where tipping was an alien concept, the influx of Europeans and Norte Americanos was probably making it more common in places like Copacabana. I left five bolivianos for the waiter, about a ten percent tip. "Gracias!" the waiter exclaimed, a bashful grin overtaking his face. Perhaps tipping was indeed unusual in these parts.

We walked back to the Hostal Cúpula as a steady wind picked up from the lake. The rain clouds were still suspended over Titicaca but were fast approaching. Thankfully we reached our room before the skies opened up and soaked us. As we both got ready for bed, the rustle of leaves transformed into a howling shriek as nature's wrath reached Copacabana. I couldn't see the rain coming down but the bending of trees and the horizontally flaring clotheslines made it pretty obvious a nasty squall was passing though. Technically this was the dry season in Andean Bolivia but with the recent El Niño, who knew what might happen here on the lake. All we could do was hope that the storm would pass and give us some peace for our remaining days in Copacabana.