|

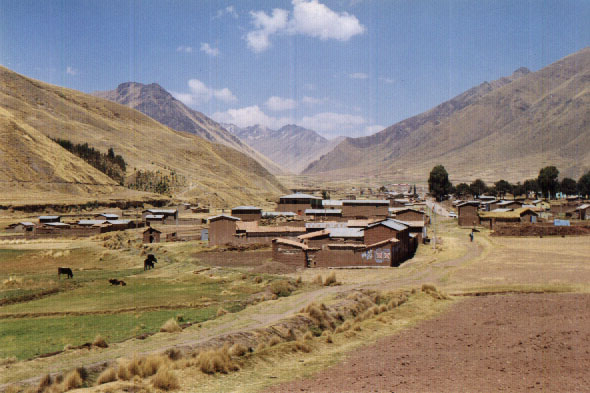

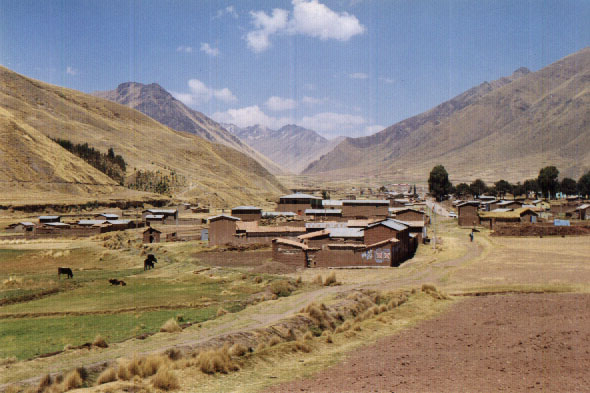

| View of the Peruvian Altiplano |

I hit the snooze button at least twice this morning. A few minutes before 7am I finally rolled out of bed and put on some shoes. For all we knew, Luis could be stopping by in 20 minutes to take us to the train station but my stubborn, sleepy head continued to argue for a 9am departure time. I needed to check with the front desk. Now what was that phrase I needed to remember...

"Cuando el trén... Cuando.... Dammit.... Susanne!"

"Cuando el trén para Puno sale," she muttered, half asleep.

"Cuando el trén para Puno sale." I repeated yet again. "Why did I have to study French in high school? Cuando el trén para Puno sale..."

"Cuando el trén para Puno sale?" I asked the man at the hotel reception, brimming with linguistic confidence.

"Ocho," he replied, smiling.

Uh oh - eight o'clock. Luis would be here in less than 15 minutes. "Susanne!" I yelled as I entered the room. "Get up! Gotta go at 7:15." Fortunately we had never really unpacked the night before so it only took a moment or two to get our backpacks in order. The harder task was waking up and getting dressed with enough warm layers to withstand the chilly Cusco morning. Around 7:10 I stepped outside the hotel gate to the Plaza de Armas, just in case Luis arrived early. "No one's ever early in South America," I muttered to myself. Yet within a minute or two Luis and a driver pulled up in their minivan. "Good Morning, señor!" Luis greeted me. "Is your lady friend ready too?" As I turned to yell for Susanne she came through the gate, tightening her backpack around her waist as she walked. We were on our way with plenty of time to spare.

We briefly stopped at a small hostel north of the plaza. After waiting a few minutes a bearded man with wire spectacles and fiery red hair down to his shoulders boarded the minivan with the largest backpack I've seen in years. He looked strikingly similar to Dr. Bob Bakker, the flamboyant paleontologist who always seems to have a special on the Discovery Channel. He climbed behind Luis and started chattering away with him in fluent Spanish. I saw the luggage tag on his backpack: San Jose. No surprise - he had that Bay Area thing going on alright.

The five of us drove through the empty streets of Cusco before reaching the southern train station. I had forgotten Cusco had two major train stations, one for Machu Picchu trains and the other for Puno and Arequipa trains. We approached the station from behind and were let through a security gate by armed guards. With the crowds of touts outside the station I felt better knowing we'd be allowed to drive right up to the terminal without having to worry about pickpockets. After buying a bottle of agua sin gas we boarded the train, only to find that someone had already placed their luggage in the small rack above our seat. No problem, I figured; we'll just place our bags in one of the many other racks that were still available. The backpack above us, though, was one of those huge trekking packs that towers well over your head when you wear it, and nearly half of the bag was drooping over the side of the rack, two feet above Susanne's head. I could tell already I'd have to watch that thing for the next eight or nine hours.

The train soon filled up with fellow travelers, including several groups of German, French and British backpackers. A young Dutch couple sat directly across the table from us. They never said they were Dutch - they hardly said anything at all - but they were both reading large books that were clearly written in Dutch. To our right, just across the aisle, were two middle-aged French couples. Almost as soon as the train departed for Puno they pulled out a sack of fresh bread, a large chunk of cheese and eight small containers of yogurt. These folks knew how to travel, I thought, as I looked at our meagre water bottles and pieces of semi-stale caramel pastry.

For the first half hour of the trip Susanne and I both attempted to write in our journals. Both of us had fallen terribly behind already - in my journal we were still on our first train ride heading to Machu Picchu. The Puno train offered a much smoother ride than the narrow-gauge Machu Picchu train, but not smooth enough for either of us to write legibly. "I tried that on our train to Cusco," the Dutch woman across from us said, pointing to my journal. "I gave up before you did." I looked at the page or so I had written that morning and quickly realized that I could barely read anything I wrote. It was difficult enough reading my poor penmanship when it's written on a stable surface. There was just no way I was going to get very far writing today. I returned the journal to my daypack, looked out the window and watched the sunrise over the Andean hillside.

The morning passed quickly as the train continued south, gently rocking back and forth down the track. Cusco was now about 100 kilometers behind us. We were now in the heart of the Altiplano - the Andean high plains. Even though the Andes stretch far down the western slope of South America, not all of the range is made up of soaring snowcapped peaks. Between here and Lake Titicaca (another five hours to the south) and continuing into western Bolivia, the Andes flatten out into a lofty plateau surrounded by rolling hill country. I've heard the Altiplano described as bleak and desolate, but here at least the scenery was acre after acre of plentiful farmland, small villages and grassy hillsides. Herds of cows, sheep and alpaca graze the fields on both sides of the train. I was particularly excited to see alpaca in their traditional surroundings. Every llama and alpaca we had seen up to this point had been for the benefit of tourists only (though the llamas of Machu Picchu primarily served as natural lawnmowers). Now we were far from tourist country, surrounded by farms and pastures. It was as if Montana had been transplanted south of the equator and dumped on a plateau 13,000 feet above sea level.

As we continued southward I paid more attention to the herds of black and white sheep. On some occasions the train would ride just alongside a pasture, allowing me to get a closer look at the grazing animals. Suddenly it occurred to me that I hadn't been staring at sheep - they were long-haired alpacas! Farmers shear their alpacas once every year or two, and if you wait long enough the alpaca wool will get extremely long and bushy. These "sheep" were actually alpacas in dire need of a shave. Most of them had been grazing in the grass so I couldn't see their distinctively long necks. Now that I was a little closer I spotted numerous alpacas with their heads held high, as if someone with an odd sense of humor had cloned a sheep with a miniature giraffe.

Apart from the beautiful countryside the train ride itself was uneventful. A pair of German backpackers, one of whom had stacked their pack so poorly above our heads, annoyed the bulk of the train car by beginning to smoke. You could see passengers' discontent spread as the smoke drifted further down the aisle. One of the Frenchmen next to us sniffed the air in disgust and mumbled "Fume" to his companions. A few minutes later a train steward entered the car and promptly ordered the Germans to take their cigarettes outside between the cars or to put them out. "Thank goodness," I said, "Non-smoking actually means non-smoking then." The Germans continued to cause trouble by trying to climb onto the train roof from outside the car. Once again they were rebuffed by the stewards and told to sit down.

We then made a quick two-minute stop at the country village of Sicuani, which gave me enough time to step outside in search of something to eat. Several campesinas approached me with buckets of candy and peanuts, but nothing substantial. Someone, I figured, had to be selling empanadas, sandwiches or something filling. "Pan, por favor, señora," I yelled out from the train. One of the campesinas near me turned her head and repeated, "Pan!" which was then repeated by yet another woman. A moment or two later a young woman ran up to me with large round loaves of fresh bread.

"Pan, señor!" she said.

"Cuanto cuesta para uno pan, por favor?" I asked.

"Uno sole, señor."

I guessed the loaf would actually cost a fraction of that, but with the train about to depart I wasn't going to argue over 30 cents. I paid the campesina and returned to our car as hungry backpackers all eyed my warm loaf of bread, its fresh smell overpowering the smoky odor left by the German fellows.

There wasn't much to do on the train so every now and then I'd wander outside to the small platform between the cars. I brought my camera with me and did my best to steady myself to get some pictures of the countryside. "Why don't you sit down," a tall Italian man said to me, pointing to the outer steps as he smoked a hand-rolled cigarette. This is how people fall out of trains, I thought to myself.

"I am quite serious," he said. "Sit down with you back to this wall and place your foot here," pointing to the edge of the door frame. "If you do this and hold on with one hand you can then take good pictures with your other hand." He then quickly squatted to the floor and demonstrated. It seemed reasonable enough, so I got down and planted my right foot squarely into the door frame. There wasn't much room to get comfortable, but my pressed foot indeed locked me into place. With the cool late morning wind rushing through my hair I leaned outside the train and snapped some pictures. "Trains are wonderful, aren't they?" the Italian smiled, taking another drag from his cigarette.

Just before noon the train stopped at the market town of Santa Rosa, halfway between Cusco and Juliaca. Unlike most other stops which usually lasted for 10 seconds or less, we spent 15 minutes here, allowing many of the passengers to get outside and stretch. Susanne stepped outside to walk around the platform while I again leaned out the door, this time purchasing a two plastic bottles of Diet Coke and Sprite. Once the train started to roll we discovered the bottles had been shaken a bit; the Sprite fizzed all over Susanne. She wasn't pleased.

Lunch was available on board for 20 soles, about seven dollars. Not exactly a bargain by Peruvian standards, but I was so hungry I relented and ordered the roasted chicken. Around 1pm the chicken arrived with an onion and avocado salad as well as a thimble-sized pisco sour. The chicken was surprisingly delicious and generous: a roasted half chicken with a tangy (and messy) barbecue sauce. Even Susanne, who hates chicken on the bone, enjoyed it immensely. It was by far the best food I've ever encountered on a train. I certainly made a mess of it, though, and was in dire need of Susanne's collection of Wet-Wipes in order to get the sticky red sauce off my fingers.

Not long after 4pm the train pulled into Juliaca, a major transportation hub just northwest of Lake Titicaca. I had initially thought we were going to depart the train here; there was a series of switchbacks between Juliaca and Puno so it was actually much faster to catch a minibus from Juliaca instead of enduring the rest of the train ride. Back in Cusco, though, Luis insured us that the switchback process didn't take as long as it used to, so we would be met by our local guide, Zacharias Quispe, on the tracks in Puno between 6pm and 7pm, depending on when the train arrived. As the train sat in Juliaca, I walked around the car to stretch my legs, poking my head out the door to see what was going on. About five minutes into our stop a thin Peruvian man with dark Aymara features climbed onto the car and asked loudly, "Su-sahn Cornwall?" Susanne and I immediately looked up and introduced ourselves. "My name is Zacharias Quispe," he said, tilting his large hat above his head so we could see more of his face. "We are driving to Puno. You must get off quickly."

features climbed onto the car and asked loudly, "Su-sahn Cornwall?" Susanne and I immediately looked up and introduced ourselves. "My name is Zacharias Quispe," he said, tilting his large hat above his head so we could see more of his face. "We are driving to Puno. You must get off quickly."

We were both surprised to see Zacharias in Juliaca so we rushed to grab our bags off the luggage racks, to which they had been secured tightly for the bumpy train ride. Zacharias carried Susanne's bag as we departed the train and walked to a minivan parked across from the train station. "We weren't expecting you here," I told Zacharias. "I know," he said, "but it will be two hours before the train gets to Puno, and we can drive there in 45 minutes, so I thought I would pick you up here. We will be in Puno before 6pm." I wondered if this courtesy was going to cost us an arm and a leg but I appreciated the chance to get off the train an hour or two early. Susanne and I were joined in the minibus by a young Irish couple, Joe and Fiona. They were heading to La Paz by way of Puno after having spent a few days in the Peruvian Amazon.

The drive to Puno passed quickly as we talked to Zacharias, Fiona and Joe. I told Zacharias we planned to go to Bolivia the next day. "I can help you get to Copacabana and La Paz, if you would like," he said. The bus ride from Puno to Bolivia shouldn't cost us more than five or ten dollars, so I told him we could talk about it at the hotel in Puno. The sun began to set over the Altiplano, which had now become flat, desolate farmland with steep hills far in the distance. "This could be the Dakotas, in North America," I said. "It certainly looks like the Far West to me," Joe replied. I continuously adjusted the window curtain to my right in order to get out of the direct sunlight. We were just below 4000m, above 13,000 feet; the high altitude and thin atmosphere was a recipe for severe sunburns, especially near Lake Titicaca. "From now on we use SPF 30," I said to Susanne, dabbing some suntan lotion on the right side of my face and neck.

Around 5:30pm the minibus began to descend into a steep valley, revealing the city of Puno below. Puno is Peru's largest port along Lake Titicaca, which we could now see to the east. Sometimes called El Lago Azul (the blue lake) for its uniquely deep blue waters, Titicaca was an immense azure expanse stretching as far as the eye could see. I've always wanted to visit this lake ever since seeing Jacques Cousteau documentaries about it as a kid. "The highest lake in the world," it's often called. While not exactly true - there are even higher, yet much smaller, navigable lakes in the Andes - at 3820m altitude Lake Titicaca is still an impressively lofty place.

As we arrived in Puno the streets became crowded with hundreds of pedestrians weaving in and out of traffic. I'd never heard anything good about Puno - "there's no history there..." "nothing to see or do..." - but I could already tell that this was a lively little city. Every sidewalk was a never-ending market, with scores of campesinas selling fruit and vegetables, pots and pans. "There are 40,000 people in Puno," Zacharias commented, and every last one of them seemed to be out and about tonight. After dropping off Joe and Fiona at their hotel, Zacharias drove us to Hostal Isla. "It's a nice place," he said, "but if it's too loud I will take you somewhere else." I noticed a large discotheque next door to the hostal - not a good sign. Susanne didn't seem to mind the noise but I asked if there were any quieter places nearby. "No problem," Zacharias smiled, "We can go to Hostal Zurit instead."

I wasn't familiar with Hostal Zurit but was eager to check it out. Susanne looked ready to drop for the night, but I said it would probably be worth going elsewhere if we wanted a good night's sleep. We followed Zacharias uphill through the pedestrian-packed streets. Our heavy backpacks combined with the steep altitude (3000 feet above Cusco, 13,000 feet above Washington DC) caused us to lag behind Zacharias, who darted in between campesinas and food carts like a cat prowling after a mouse. After walking a block or two we reached Hostal Zurit, a deserted, multistory building with an immense atrium. It seemed comfortable enough for one night - certainly quieter than the Isla - so we quickly settled in our room on the second floor. Zacharias told me if we still wanted to go to Copacabana tomorrow his tour bus could take us there for $10 each. That sounded fine with us so I paid him in soles. "I'll pick you up at 8am tomorrow," he said. "The bus will take about three hours, depending on how long you wait at the border."

By 6pm we were both getting hungry so we walked up to Avenida Lima, two blocks north of the hostal. Zacharias recommended several restaurants on Lima, not far from Puno's main square. We walked up the crowded streets to the square, which was decorated with perfectly trimmed topiary animals. "A little piece of Disney on Lake Titicaca," I said. Avenida Lima was a long pedestrian walkway packed with restaurants and cafes. Zacharias had specifically recommended Restaurant Don Piero's, though he also said most of the other restaurants along Lima were both good and safe for gringos. Don Piero's had a solid reputation for tasty food but I could tell from the outside window it lacked any atmosphere. Across the street I noticed another restaurant with a darkened interior and Andean music coming from inside. Three men with menus stood outside the restaurant, eagerly awaiting the opportunity to share them with us. They smiled as I approached them and asked for a menu. The food selection seemed fine, so Susanne and I went inside.

We both ordered chicken from the "especiales de casa" side of the menu. Susanne asked for the arroz con pollo while I selected another chicken dish which I later realized was Spanish for "dry chicken." I grimly wondered what I had gotten myself into. Along with a couple bottles of Sprite we also requested another agua sin gas. The young waitress brought out our drinks, leaving the mineral water on the table with a pair of empty glasses. I opened the water and began to pour it when I noticed the water was heavily carbonated. Strangely, the bottle's label read "agua sin gas," just as we had ordered, and not "agua con gas," which is clearly what we got. I called over the waitress and tried to explain the situation. "El agua no está agua sin gas," I said, to which she confusedly replied, "No, señor, agua sin gas," as she pointed to the words on the label. "Sí, sí, agua sin gas," I said, also pointing at the label, "para agua sin gas está agua con gas," as I then pointed to the fizzy water coming out of the bottle. Neither of us had an explanation for the situation but eventually she realized something was amiss and brought us a fresh bottle. I gave the bottle a light shake and opened it. No bubbles. "Ah, agua sin gas," I smiled. "Gracias, señorita."

A few minutes later our food arrived piping hot and smelling delicious. Susanne's arroz con pollo was a huge platter of paella engulfing a quarter roasted chicken, while my dinner was a similarly sized chicken piece smothered in steaming onions and a white wine sauce. The food was fantastic, perhaps the tastiest food of the trip. "Why can't more Peruvian restaurants offer arroz con pollo instead of egg sandwiches and french fries?" I said. We wondered if some of the tasteless food we had previously experienced was actually a side effect of the altitude medicine Diamox we were taking. Diamox, as we had discovered, left most food with an iodine taste, but it seemed our bodies were adjusting to the twice daily doses of pills. "I suppose confused having taste buds isn't that bad of a side effect for altitude medicine," I said. "Imagine if the side effect was flatulence - all of us tourists would be known to the locals as gringos con gas." Susanne and I both roared with laughter, trying our best to contain ourselves. "Gringos con gas," Susanne cried, "That's just awful..."

Our stomachs stuffed and our thirsts quenched, we returned to Hostal Zurit after a lazy stroll along Avenida Lima. It was too bad we had made our plans based on Puno's poor reputation. I think we would have had fun hanging out here for a day or two. Tomorrow, at least, we were heading to the Bolivian town of Copacabana, which had the reputation of being a lot prettier and less crowded than Puno. Copacabana would also serve as our departure point for Isla del Sol, a small island on Lake Titicaca known for its ancient Aymara villages, historic Inca ruins and Aegean-like vistas. I had high hopes for our first few days in Bolivia.

Before going to bed I visited the hostal's front desk to request a pair of extra pillows. Susanne and I had looked up the word for pillow in our Spanish dictionary - "almahadon." None of the hostal staff spoke English, so I hoped I'd pronounce it correctly. Downstairs I found a young man reading at the reception desk. "Tiene dos almahadon?" I stuttered in Spanish. "Almahadones?" he asked, as I placed my hands on the side of my face, imitating someone asleep. "Okay, no problem," he replied in English. The pillows appeared upstairs several minutes later.

As we settled in for the night Susanne and I heard what sounded like a large crowd chanting and marching down the street. "A political rally?" I asked. Susanne decided to go down and investigate. A few minutes later she returned and said, "A political candidates and his supporters. The election is in October - and somehow I managed to learn all of this in Spanish." Indeed we had seen many buildings spray painted with political graffiti regarding certain candidates. At first I thought the graffiti was done as vandalism but the more of it I saw across Peru I realized that people were probably spraying their own houses and buildings in support of their candidates. High-gloss posters and sign would be financially prohibitive here in the countryside, so graffiti made a compelling substitute.

I thought of political rallies and songs from Evita as I fell asleep, the campaign rally growing quiet as it marched away.