Phnom Penh and the The Killing Fields

|

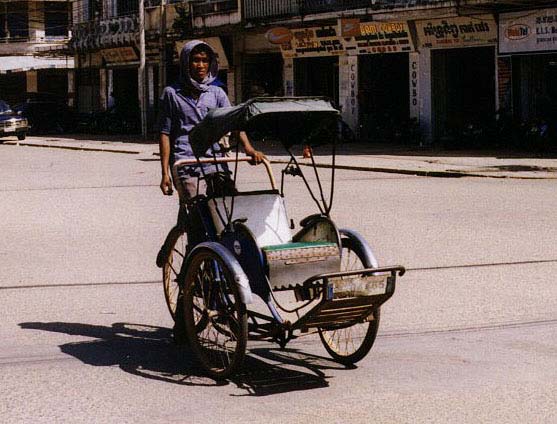

| Cyclo Driver, Phnom Penh |

As I write this, I'm sitting in a plane headed for Cambodia. Andy and I plan to stop first in Phnom Penh to witness the Killing Fields, then we will travel on to Angkor to explore the ruins.

to explore the ruins.

A couple weeks before this trip, I fished out an old copy of National Geographic from 1960. Inside there were dozens of pictures of Angkor in that glorious old grainy film... the majestic Bayon heads, the incredible outline of Angkor Wat. However, I found myself drawn not to the pictures of the monuments, but to the pictures of the people. Children playing in the ruins. A boy holding a toddler on his hip. I couldn't help but wonder, "what happened to these people?" This article was printed 15 years before the horrors of the Khmer Rouge, but these children were certainly affected. It is said that as many as two in seven Cambodians were murdered or starved to death by the Khmer Rouge. Did these children survive? Those magnificent ruins faded into a backdrop for me as I zeroed in on the children's eyes.

but these children were certainly affected. It is said that as many as two in seven Cambodians were murdered or starved to death by the Khmer Rouge. Did these children survive? Those magnificent ruins faded into a backdrop for me as I zeroed in on the children's eyes.

I cannot think of Cambodia without thinking of the Khmer Rouge. It is an unfortunate association. Cambodia has a fascinating history full of great kings and jungle temples. Thousands of years of civilization. But my impression of Cambodia has always been based on what happened over a period of less than four years.

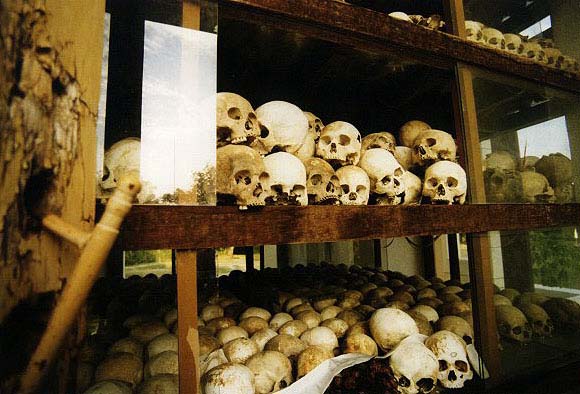

|

| Skulls of the victims of Tuol Sleng prison |

forces took a strangle-hold over the nation. Like a house with boarded windows and locked doors, Cambodia became a mystery to the rest of the world. Inside a systematic massacre was raging. People were shot if they wore glasses, if they spoke French, if they were educated. Sons bludgeoned their parents with shovels. Children starved to death. Finally in December of 1978, Vietnamese troops invaded the country and quickly drove the Khmer Rouge into the jungles. Thousands of families had been wiped out. Skulls littered the rice fields. Blood seeped into the dirt. Vietnam called Cambodia "hell on earth."

forces took a strangle-hold over the nation. Like a house with boarded windows and locked doors, Cambodia became a mystery to the rest of the world. Inside a systematic massacre was raging. People were shot if they wore glasses, if they spoke French, if they were educated. Sons bludgeoned their parents with shovels. Children starved to death. Finally in December of 1978, Vietnamese troops invaded the country and quickly drove the Khmer Rouge into the jungles. Thousands of families had been wiped out. Skulls littered the rice fields. Blood seeped into the dirt. Vietnam called Cambodia "hell on earth."

It has been almost 20 years since Pol Pot disappeared into the north, but the country is still struggling. Bandits roam the forests, land mines are buried in the fields. King Sihanouk's popularity is strong, but new issues grow out of old horrors. The US government considers Cambodia a highly dangerous destination. Americans are advised against any non-essential travel to the country. So why am I going there? I've asked myself that countless times. Certainly it is largely to see Angkor. The ruins are reputed to be among the most incredible man-made structures in the world. But I know it's not just that. In a way, I am drawn to Cambodia in the same way a person is drawn to look at a man's scars when he rolls up his sleeves. But much more than morbid curiosity, I am amazed by this country's perseverance. I respect these survivors with my entirety. Day One - April 17th, 1975 - was my third birthday. This massacre, this perversion of humanity, occurred during my lifetime. While I ran around in sundresses and played with Star Wars people in the sandbox, Cambodia tore itself apart. I have come to witness Cambodia's memorials. To see the era after the aftermath. I want to find the face of survival. As far as I can express, those are my reasons.

popularity is strong, but new issues grow out of old horrors. The US government considers Cambodia a highly dangerous destination. Americans are advised against any non-essential travel to the country. So why am I going there? I've asked myself that countless times. Certainly it is largely to see Angkor. The ruins are reputed to be among the most incredible man-made structures in the world. But I know it's not just that. In a way, I am drawn to Cambodia in the same way a person is drawn to look at a man's scars when he rolls up his sleeves. But much more than morbid curiosity, I am amazed by this country's perseverance. I respect these survivors with my entirety. Day One - April 17th, 1975 - was my third birthday. This massacre, this perversion of humanity, occurred during my lifetime. While I ran around in sundresses and played with Star Wars people in the sandbox, Cambodia tore itself apart. I have come to witness Cambodia's memorials. To see the era after the aftermath. I want to find the face of survival. As far as I can express, those are my reasons.

All the same, I must admit I am worried about our safety. For weeks I have found myself muttering, "Please Lord, no bandits, no land mines, no kidnappers." Andy knew a woman who was killed by bandits three years ago. She was on a private visit to the Angkorian ruins of Banteay Srei when she and her husband were asmbushed. The coup this last July intensified my concerns, as have the recent reports of tourists being attacked on the streets at night. But I am willing to take the risk, because this is a trip I feel compelled to take. Besides I'm on the plane to Phnom Penh. There is no turning back now.

We arrived at Phnom Penh's Pochentong International Airport around 11 AM. We walked from the plane, across the pavement to the terminal. Another American, a man in his early 30's, snapped a picture of the airport from the outside. He turned to Andy and me and said, "got to get that shot." We waited in line for visas - a cold assembly line process - until our passports were stamped "Royaume de Cambodge" with thick black ink. We headed through the terminal to look for our pre-arranged guide. I was surprised to find the airport in such stellar condition, considering that the control tower and radar had been destroyed in the recent coup. By the main entrance, a crowd of young men offered taxis. We made hotel reservations at the terminal's hotel desk. Still no guide. Finally a young man stood in the crowd holding up a sign that read Susanne C and Andy C. He smiled kindly and directed us to the car. On the way through the parking lot, a teenager walked alongside me trying desperately to sell me a newspaper. The headline read "Verdict on Pol Pot" and the teenager kept saying "Pol Pot," and looking sadly up at me. I'm not sure what that verdict was all about. Pol Pot, the leader of the brutal Khmer Rouge regime, was tried in some undisclosed jungle court several months ago. He's living out the rest of his miserable life in a mosquito infested hut with his wife and 12-year-old daughter. (Update: Pol Pot died in early 1998.)

Our guide's name was Rith (pronounced rit). He was a young, attractive man with a blue polo style shirt and trim black hair. I liked him immediately. While driving to the hotel he asked what we wanted to see. Too embarrassed to say we were mainly interested in the genocide monuments, we waited for him to reel off the sites. We nodded when he got to Tuol Sleng (the Khmer Rouge prison) and the Killing Fields monument at Choeung Ek. We also agreed that we wanted to see the Silver Pagoda.

Driving through Phnom Penh was fascinating. It seems to be a city of children. Well over half the people we saw were under 17 years old. Paved main streets branch off into dirt roads. Concrete sits uprooted along the sidewalk. Motorcycles dart in and out of cars and cyclos as vendors push their carts. There are no functional street lights. People cross when they can. Traffic moves with subtle anarchy. (Still better than LA on a sunny day.) From behind the car window I could see naked babies, children with backpacks in school uniforms, young merchants balancing baskets on their heads. Teenage women ride side-saddle on mopeds, their long dark hair swept over one shoulder. A boy no more than nine years old drives two little girls on his moped. A woman washes her baby in the shadow of an old French colonial-style apartment. The city is teeming with life and youth. Over half the current population wasn't even alive during the Khmer Rouge's reign

as vendors push their carts. There are no functional street lights. People cross when they can. Traffic moves with subtle anarchy. (Still better than LA on a sunny day.) From behind the car window I could see naked babies, children with backpacks in school uniforms, young merchants balancing baskets on their heads. Teenage women ride side-saddle on mopeds, their long dark hair swept over one shoulder. A boy no more than nine years old drives two little girls on his moped. A woman washes her baby in the shadow of an old French colonial-style apartment. The city is teeming with life and youth. Over half the current population wasn't even alive during the Khmer Rouge's reign

The buildings look as though they could have once been grand and modern. But dust and decay coat much of their once glorious facades. Dogs lounge in the shade. Puppies play around the food stalls. It seems to be a city without a time period. It's not like going back in time, not as if technology just hasn't arrived yet. I've been to places like that... Varanasi, India, and to a certain extent, Venice, Italy. But Phnom Penh isn't like that. It was like too much time had passed, and a once prosperous city was worn out, frayed. But what I saw in the buildings I did not see in the people. Young children ran and laughed. Women on mopeds smiled shyly at me. The city I now call home, Washington, D.C., seemed sterile compared to Phnom Penh's action and youth. "Life goes on," the old saying goes. So it does.

Rith dropped us off at the hotel and said he'd be back at 2 PM to show us the city. He walked us up to the Hawaii Hotel's main desk and waited while we checked in.

"How old are you?" I asked.

"29," he smiled. "I was born in the year of the rooster."

He was born, then, in 1968. He was seven when the shit hit the fan here. I wish I could have asked him about his life, but that would be terribly inappropriate. He would offer the information if he wanted to, I figured. Everyone my age or older here is a survivor, a witness, a victim. My train of thought was broken when the hotel staff greeted us with pink papaya drinks. The air was heavy and humid, and those drinks were damn good.

The hotel was strangely empty. We were the only customers in this enormous dining room with straw woven chairs and glass chandeliers. It seemed so strange to be the only guests in this grand room. Outside the window, children played on the curb. Schoolboys walked by. Two other tourists, American men in their thirties, followed a guide to a car. All the foreigners here have the same look on their faces - a look that seems to say, "I don't know what the hell I'm doing in Cambodia, but it's pretty cool."

After lunch we figured we had some time to kill before Rith came back, so we headed out to the nearby Central Market. We dodged cars, crossed the streets, passed toddlers walking clumsily on the sidewalk, and stopped in front of the flower market. Young women sold flowers from buckets of bouquets. Awnings or sheets of cloth covered the stalls.

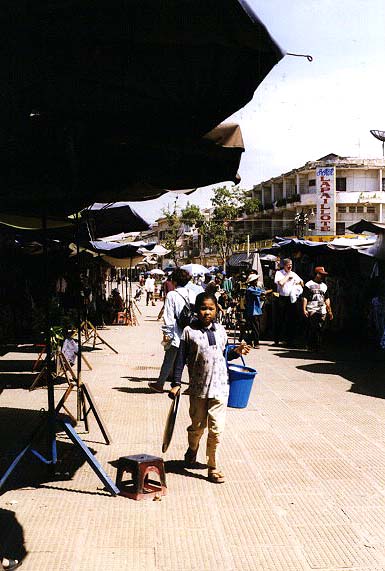

|

| Central Market, Phnom Penh |

We walked into the domed marketplace. It was enormous. Sunlight shot through slits in the high ceiling and fell on the mazes of merchant stalls. Watches, radios, gems, clothes - you name it. Wooden reliefs of Angkor Wat sold next to underwear. Middle age women tried on bras over their clothes. A boy maybe 10 or 12 years old came up to us. His brown shirt was torn and ripped, and he was speaking in very broken English and French. I couldn't quite understand what he was saying, but he clearly wanted money. I wasn't carrying anything under a five dollar bill, and Andy argued that we only had five singles, and we needed them since it was a weekend and we couldn't cash our traveler's checks. I know in theory that you are not supposed to give money to children, but I wished I had a buck on me anyway. He tailed us through the market, following not more than an arms-length away. Most of the time he walked right next to my elbow. We had become involved in a tragic game of dodging and hiding. We walked faster. We slowed down. We tried to weave into the maze of cloth stands. He never missed a turn. Finally, I realized that every time we went near the police sitting at the entrance, he had to back away. So we stood at a stand there and pretended to be interested in the gems.

"What's this?" Andy pointed to a large fang.

"Tiger's tooth," the woman answered and laid it on top of the glass in front of him.

Finally, when the boy wasn't looking, we dodged into the outside market stalls. The market really is a maze of people, cloth and stands, and after a few turns we knew we had lost him. A young girl smiled at Andy and pointed to her cloth. He smiled back and said no thank you. She laughed shyly and waved good-bye. Andy bought some scarves, but after maybe twenty minutes we decided to leave the market. The boy and the amputees reminded us that we were not invisible observers here.

At 2 PM we met Rith and the driver in the hotel lobby, and headed out to our first stop, the Silver Pagoda. Housed in a gated courtyard near the palace, the Silver Pagoda and its adjoining grounds are incredible. Sweeping roofs, panel paintings of the Ramayana, lion statues, and stone nagas create a majestic display. Even more incredible is the fact that these structures, the Emerald Buddha and the solid gold, diamond studded Buddha survived the Khmer Rouge.

|

| The Silver Pagoda, Phnom Penh |

The grounds, like our hotel, were strangely empty, especially since we'd just come from Bangkok where the wats were so choked with tourists that you couldn't avoid getting twenty of them in every photo. Suddenly a group of school children arrived - boys and girls about junior high age in blue and white uniforms. They pointed at us, smiled, waved and finally approached us with a camera. They wanted to take our picture. We happily agreed and the kids gathered around us for a shot. After their photo we asked them to pose for us. It was a wonderful experience. They were so cute and excited. I guess they don't see many tourists anymore.

Outside as we waited for the car, an amputee limped up to us asking for money. In the distance ten foot pictures of Sihanouk and his wife were plastered onto stone fences. The Cambodian flag - blue and red with an outline of Angkor Wat - flapped in the wind.

Tuol Sleng

Tuol Sleng isn't very far from downtown, but once we left the main street, the dirt roads were bumpy and punctured with pot holes. More children, dogs and vendors lined the streets. A sign on the white gate read, in English and Khmer, "Tuol Sleng - Museum of Genocide." Children peddled bikes too big for their bodies around the gate. An old woman stood next to her fruit stand. Boys played tag. We drove past the sign and into the prison.

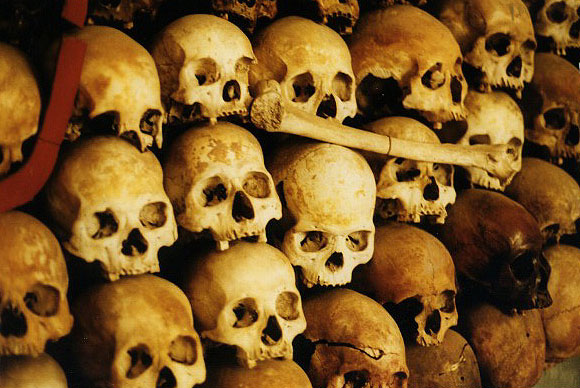

Over 17,000 people were brought here during the Khmer Rouge's reign. Seven people survived. In this gentle setting that used to be a high school, victims of the Khmer Rouge were tortured and murdered. Men missing legs came up to us as we got out of the car. We paid the entry fee of two US dollars and met our guide, a middle aged woman named Phalla (pronounced Pala).

The campus consisted of four buildings congregated around a grass courtyard. The bright sunlight revealed where paint had chipped off the walls. A thin, lanky man swept off the fourteen graves in front of the first building. In these graves lay the last fourteen people killed at Tuol Sleng. A monk in saffron robes and black rimmed glasses followed in the tour behind us.

The first building housed prisoners on two floors. They were chained to metal bed frames. No mattresses, only hard metal. On the walls, hanging above each bed, were photographs of the dead found in each room after the Vietnamese wrestled the city from the Khmer Rouge. In one cell, a photograph showed a naked body, wretchedly twisted, handcuffed and shackled. He had been killed with a shovel. White bits of cheekbone were exposed. A pool of blood gathered under his bed. This was the very room where he was found. The room where he was tortured and murdered. I looked around the cell. In his anguish, that prisoner must have focused on the bits of dust encrusted in the walls. He must have seen how the plaster had fallen off the walls in fist-sized chunks. He must have seen those spots where the paint changes hue on the ceiling. This room had been a tomb for the living, and I was surprised somehow by the amount of light. The window was covered with a series of slates which allowed strips of sunlight to pour through. Past the window slates I could see a little girl on a tricycle, riding just outside the prison. I could see green trees, houses, people working in their backyards. I turned around and looked out towards the outside hallway. A monk in the small tour group behind us was standing at the cell window looking in. He had his hand up to his mouth. The prison cell reflected in his thick glasses.

Our guide Phalla pointed out a sign hanging in the hallway. It had been translated into English. This sign greeted the prisoners of Tuol Sleng. It stated such prison rules as "The prisoner will not cry or yell out while receiving lashes." Each line of horror was stated as a matter of fact.

The next building was even more haunting. The Khmer Rouge kept meticulous records of their work. Every prisoner was photographed upon arrival. Some were photographed in their rooms, chained to their beds, but most of the prisoners were forced to sit on a thin wooden chair with a rod stemming out from the back that directed where their head should be. This collection of photos is the victims' last testament. A woman, hair cropped holding a baby stares out from one photo. A boy with his mouth bloodied and swollen, blood smeared up his cheek. A young man with his arms pulled behind him stares into the camera. His eyes bulge with terror. Every shot is black and white, making them seem ever the more like evidence. Rows upon rows of evidence. Walls and walls of evidence. Some of the victims smiled innocently into the lens. Shards of sunlight poured across the pictures. The few foreigners who died at Tuol Sleng also have a place on the wall. An Australian businessman who missed his chance when the world evacuated from Phnom Penh. A westerner with a scraggly beard and wide horrified eyes. One photo struck me the hardest. A boy no more than twelve years old with cuts on his cheeks and around his eyes. A heavy metal chain hung around his neck like a leash. Tight jaw, dark eyes.