|

| Tiger and snow leopard skins, Thakhilek market |

Monday, November 17

Daytrip to Burma; The Chiang Rai Night Market

Neither Susanne nor I had a good night's sleep, so we decided that the first thing we'd do after breakfast was find a better place to stay. The garden setting at the Mae Hong Song Guesthouse was certainly quaint and the staff very friendly, but all of that was pretty meaningless when you wake up with bruises on your side from sleeping on a rock-hard bed. We did, though, want to visit the guesthouse's trekking office to hear about any two-day treks they offered. The resident guide told us about an exciting, yet grueling trek that would include about four village stops. We'd think about it. The trek sounded like fun, but we recognized we were nearing the end of the trip and probably needed some rest. Susanne hadn't slept well in days, so this two-day trek might be more than she bargained for. I suggested we check into a better hotel, take a day trip to Burma, and then head to Chiang Mai the next morning. This would give us several days to reevaluate our ability to handle a trek.

A tuk-tuk brought us a kilometer down the road to the Golden Triangle Inn. The Inn had received high praise in some of the travel guides and it seemed like a lovely place, with lush gardens and blocks of teak bungalows. And at 600 baht ($15) a night, including breakfast, it was a really great deal, assuming we could find a vacancy at the place. The front desk told me they had one double available as long as we didn't plan to stay more than three nights. That wouldn't be a problem for us, so we settled into the room and cleaned off the grime from the guesthouse, the bus, a ferry, a sampan

brought us a kilometer down the road to the Golden Triangle Inn. The Inn had received high praise in some of the travel guides and it seemed like a lovely place, with lush gardens and blocks of teak bungalows. And at 600 baht ($15) a night, including breakfast, it was a really great deal, assuming we could find a vacancy at the place. The front desk told me they had one double available as long as we didn't plan to stay more than three nights. That wouldn't be a problem for us, so we settled into the room and cleaned off the grime from the guesthouse, the bus, a ferry, a sampan , two speedboats, two samlors

, two speedboats, two samlors , a jumbo

, a jumbo and a couple of tuk-tuks that we had taken in the last 24 hours. Feeling refreshed and groomed, we headed down to the city bus terminal to spend the afternoon in Burma.

and a couple of tuk-tuks that we had taken in the last 24 hours. Feeling refreshed and groomed, we headed down to the city bus terminal to spend the afternoon in Burma.

Burma, now referred to as Myanmar by its isolationist military regime, shares a long, sealed border with Thailand, save a handful of crossing points that allow visitors to take daytrips. One such crossing point was at Mae Sai, the northernmost town in Thailand. Mae Sae sits in the heart of the so-called Golden Triangle, the region containing the point on the map where the borders of Thailand, Burma and Laos meet. Mae Sae sells itself as a frontier outpost town where Burmese traders ship legal and illegal goods from China to the south while Thai traders do the same with Thai, Malaysian and Indonesian goods going north.

But gone are the days when the Golden Triangle was the legendary epicenter of regional insurgency and violence. Over the decades you could find a variety of rebel armies calling this area home: the Burmese Communist Party; the Shan United Revolutionary Army, the Shan State Army and the Shan State National Army, all associated with the infamous opium warlord Khun Sa; the Kuomintang (KMT), its aging units living in exile following the failed nationalist struggle in China; the Karen National Union, Karenni National Progressive Party and Karen hilltribe separatists fighting for independence from Burma; the Thai Serai (Free Thai), the anti-Japanese resistance movement left over from World War II; the People's Liberation Army of Thailand, one of the few Indochinese communist insurgencies not to make any headway in this part of the world; and the Hmong Resistance, General Vang Pao's reknown anti-communist, CIA-supported counterinsurgence force that was defeated (though not eliminated) by the communist Pathet Lao in the 1970s.

At one time or another, most if not all of these forces exploited revenues raised from the Golden Triangle's prosperous opium and heroin ventures. Many also received support from the CIA, Vietnam, or the Myanmar military, sometimes even playing one covert supporter off the other just to get more cash. The Triangle's most notorious rebel is undoubtedly Khun Sa, the Shan/Chinese opium smuggler and guerrilla leader who spent the better part of the last 40 years making enormous sums of money off processing opium into heroin. Khun Sa occasionally received support from the Burmese military and the CIA when the opportunity presented itself. Today Khun Sa is in semi-retirement on an island off the cost of Burma, but the struggle continues: his successor, Sao Sai Nawng, has successfully merged the Shan United Revolutionary Army with the Shan State Army and the Shan State National Army under the new, yet longwinded title "The Shan State National Organization and Shan State Army," or SSNOSSA. With a reputed strength of nearly 15,000 men, Sao Sai Nawng's SSNOSSA will undoubtedly be a thorn in the side of the Myanmar regime. Apart from these rebels, the Golden Triangle is decidedly mellower today; the communist movements have either fizzled out or become mainstream political parties, and the Hmong forces now focus their energies on diplomatic resistance instead of guerrilla warfare. Only SSNOSSA and the Karen separatists continue to make noise in the Triangle, mostly within the confines of Burma. Mae Sai, once a Who's Who of Indochinese intrigue and conspiracy, has now resigned itself to being a seemingly endless duty-free shop.

A bumpy two-hour bus ride brought us to Mae Sai for 20 baht each. From the bus terminal we caught a songthaew in search of the Thai Immigration Office, where we would supposedly leave our passports and get the paperwork to let us into Burma for the afternoon. Riding the crowded pickup truck, we saw a large billboard sign reading "Thai Immigration Office" with a huge arrow pointing right. We stopped the songthaew, paid the driver and went to the office, only to discover that it had moved a kilometer north; they hadn't the time yet to take down the old sign. Irritated, we waited for another songthaew to take us to the real immigration office - or so we hoped it would be real. Once there, we discovered it was closed for lunch. We crossed the road and sat at an Inter-Suki sukiyaki joint for half an hour, drinking Pepsis and watching a fascinated wait staff wonder why on earth we came there for soda but not sukiyaki.

|

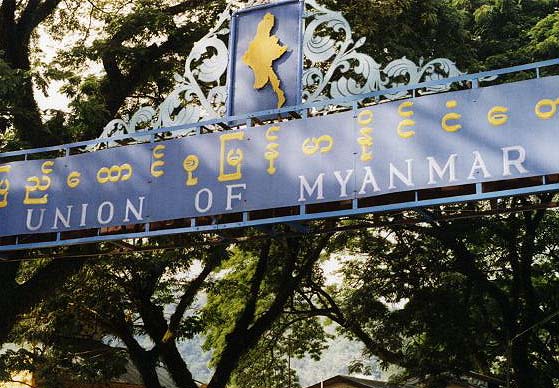

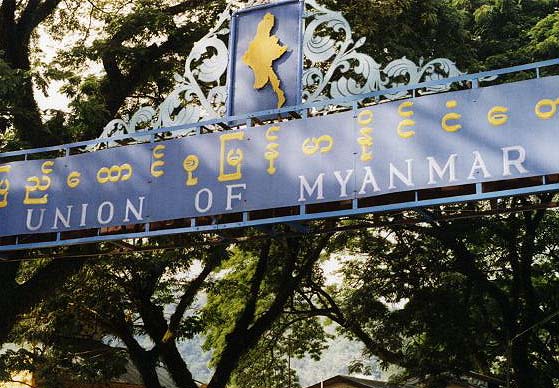

| Myanmar border crossing |

At 1pm we entered the immigration office (finally), which sent us across the street again to a copy place to xerox our passports before heading to the border point, one kilometer north. The border immigration officers, it turned out, required neither the xeroxes nor the need to hold onto our passports. We each paid 200 baht and crossed the bridge into Thakhilek, a prosperous Burmese border town. A sign over the bridge welcomed us into the "Union of Myanmar." Several beggars waited for us in No Man's Land, standing in the middle of the bridge - how on earth did they get permission to do that? They harassed us as we crossed but soon lost interest in us when they saw we were ignoring them. At the opposite end of the bridge, a greasy Burmese immigration officer stamped our passports, inspecting each page one at a time. His arms were covered in cheap graphite tattoos and he was sweating through his khaki uniform under his arms and along his collar. As we stood there, he stared at us with the grin of a boy who'd been up to no good. Our right to enter this country rested in his hands. Eventually, he looked at us and said in a stilted English, "Thank you - have a nice visit," before waving us on to the streets of Thakhilek.

|

| Snow leopard skins, Thakhilek market |

Beyond the bridge I could see a large Burmese pagoda to our left; upon closer inspection I realized it was actually a duty free shop. Burmese tuk-tuk drivers hounded us for rides, one after another, like camel guides at the pyramids of Giza. There wasn't much going on in Thakhilek apart from the markets and its many itinerant shoppers, so we spent the early afternoon wandering the maze of stalls just to see what's hot in a busy Asian border town like this one. Many of the shops specialized in teak goods - mirror frames, masks, Buddha images, drink coasters. Nice wood, but mirror frames weren't exactly a portable souvenir. Deeper into the market, though, the commodities got distinctly seedier, with illicit goods hanging besides household appliances and flea market junk. In any given shop you could easily find opium scales (smuggler's desktop scales - not your run-of-the-mill addict's pocket scales), Mr. Microphones, pornographic videos, wristwatches, decorated monkey skulls, fake leather jackets, men's underwear, animal skins. Lots of animal skins. In the course of the afternoon we easily saw about a dozen tiger and snow leopard skins. The skins of these increasingly rare cats are contraband in Thailand in the US, but here in Burma they were all available for the right price. The commercialized carnage continued with leopard skulls, tiger heads, canines, claws mounted into ashtrays and cup holders. Even the legitimate shops sold an incredible variety of pulverized animal parts for medicinal purposes, all in bags labeled in Chinese, most of them sporting a cartoon picture of a tiger on the front.

As we waited for a ride back to the bus station, I realized something else that hadn't occurred to me while we were in Burma: the high number of vendors selling prunes. Pitted prunes. Unpitted prunes. Sunsweet Lemon Essence prunes. Prune juice. Prune jam. Prune extract. And when we jumped into a songthaew we were joined by two Thai men who were both sporting bags of prunes, more prunes and a couple of cans of raisins. Was there some kind of laxative tax in Thailand? Was regularity considered a luxury or a sign of status among the Thai people? I was tempted to ask them straight up: "Why all the prunes, guys? Not feeling very regular this year?," but I couldn't think of how to say it with a straight face. I would just have to wonder. But if I had only known that dried plums were such a prize in Thailand I would have brought a second backpack with me for smuggling purposes. Better send a letter to the Sunsweet folks and ask for a finder's fee.

we were joined by two Thai men who were both sporting bags of prunes, more prunes and a couple of cans of raisins. Was there some kind of laxative tax in Thailand? Was regularity considered a luxury or a sign of status among the Thai people? I was tempted to ask them straight up: "Why all the prunes, guys? Not feeling very regular this year?," but I couldn't think of how to say it with a straight face. I would just have to wonder. But if I had only known that dried plums were such a prize in Thailand I would have brought a second backpack with me for smuggling purposes. Better send a letter to the Sunsweet folks and ask for a finder's fee.

Back in Chiang Rai we had dinner at a Thai diner - chicken soup, minced chicken and rice. Pretty unextroadinary stuff overall. We saw an elephant outside the restaurant but couldn't figure out exactly what it was doing. Delivering goods perhaps. We then decided to visit the night market just to check out the local action. As we entered the bazaar I found a great red Gumby tie for two dollars. Susanne wanted to buy an embroidered elephant baseball cap for herself and her sister. The initial asking price was 100 baht each, but we managed to bargain down to 40 baht. They probably cost only a dime to make, but a buck for a baseball cap was decent in my book.

There were several older women in Akha tribal costumes, black caps covered in silver coins on threads with a large flat plate of silver over the back of the head. One of the Akha sold opium paraphernalia - pipes, scales, etc. I noticed she had some dried poppy flowers as well, so I decided to inspect them. For dead flowers they were very pretty but I didn't think I wanted to deal with the customs hassle, to say the least. She also sold small T-shaped scalpels. I picked one up and asked in Thai, "For opium?" The old Akha picked it up and moved the metal in a scraping motion, nodding her head in affirmation. This was the tool used to nick the poppy bud, causing the opium resin to flow out and harden for collection. Next to the scalpel were several nondescript leather boxes. "Nee arai?" I asked - "What is this?" She opened it and showed me a smaller box inside. Oh, I thought, a dull version of Russian matryoshka dolls, boxes within boxes. I put the box down, but she quickly handed it back to me and motioned for me to open the rest of it. Inside, I found yet another box, but inside this one there was a dark, gummy substance wrapped in foil. Uh oh. The Akha had a large smile on her face. "Fin, chai mai?" I asked. Was this really opium? "Chai," she nodded, "fin dee mahk mahk." Very good opium, apparently. I didn't know how to say the Thai equivalent of "No thanks, lady," (Mai khop, khun Akha, perhaps?), so I shook my head and smiled, politely placing the box on her carpet. "Mai pen rai," she said, laughing. "It doesn't matter." Interesting how the local drug dealers were so grandmotherly, I thought.

But my image of playful elderly opium hawkers was shattered within 30 seconds when a thin, shady looking fellow grabbed me hard by the arm and shoved another handful of foil in my face. "You want? Yes? I know you want." "No," I responded, "Go away. Pai!" He gave me the evil eye and walked away, staring at me as he backed into the shadows and vanished in the crowd.

I rejoined Susanne and we walked through the back of the market where numerous artisans displayed carvings, paintings and handicrafts. An old couple from the Yao tribe sat next to a pile of woven blankets. Susanne found a large yellow blanket with an elephant pattern on it. "How much?" I asked. "See loi baht," the Yao woman said. 400 baht, about 10 dollars. Even if this blanket had been machine made, which I somewhat suspected, it was worth ten bucks, and Susanne clearly liked it. But just to test my bargaining skills I offered 200: "Phaeng pai, khap. Song loi baht." The couple laughed. 200 baht was a joke and they knew it. "Very good, very good," the woman said. "Yao made. Saam loi baht." So now we were down to 300 baht. I tried for 250 but got nowhere as her husband chimed in, "Yao made. Help Yao. Very good." At 300 baht, it was only eight dollars. Susanne gave me a look that said "Stop messing with these people. They need the money." "OK, no problem," I said. "Saam loi baht - OK." Susanne had her blanket. Now we could go to sleep.

brought us a kilometer down the road to the Golden Triangle Inn. The Inn had received high praise in some of the travel guides and it seemed like a lovely place, with lush gardens and blocks of teak bungalows. And at 600 baht ($15) a night, including breakfast, it was a really great deal, assuming we could find a vacancy at the place. The front desk told me they had one double available as long as we didn't plan to stay more than three nights. That wouldn't be a problem for us, so we settled into the room and cleaned off the grime from the guesthouse, the bus, a ferry, a sampan

brought us a kilometer down the road to the Golden Triangle Inn. The Inn had received high praise in some of the travel guides and it seemed like a lovely place, with lush gardens and blocks of teak bungalows. And at 600 baht ($15) a night, including breakfast, it was a really great deal, assuming we could find a vacancy at the place. The front desk told me they had one double available as long as we didn't plan to stay more than three nights. That wouldn't be a problem for us, so we settled into the room and cleaned off the grime from the guesthouse, the bus, a ferry, a sampan , two speedboats, two samlors

, two speedboats, two samlors , a jumbo

, a jumbo and a couple of tuk-tuks that we had taken in the last 24 hours. Feeling refreshed and groomed, we headed down to the city bus terminal to spend the afternoon in Burma.

and a couple of tuk-tuks that we had taken in the last 24 hours. Feeling refreshed and groomed, we headed down to the city bus terminal to spend the afternoon in Burma.