Primal Scream

Henry Rollins Speaks

By Andy Carvin and Chris Crone

"Sometimes I feel like Kurtz and sometimes I feel like Willard and sometimes I feel like they're my fathers. I've probably read a bit too much meaning into that movie."

Francis Ford Coppola's Apocalypse Now is a classic nightmare of insanity, violence and self-exploration. Post-punk iconoclast Henry Rollins embodies this nightmare.

Once upon a time, a long-haired 20-year-old Henry Garfield grabbed the microphone during a performance of seminal punk rockers Black Flag. Two weeks later, they invited him to become their new vocalist. Leaving his abusive father's surname and his job at Haagen Dazs behind, Rollins gained notoriety in the early '80s as the over-tatooed and angry voice of the anti-establishment.

Following their split in 1987 (and a short, but humorous tour of duty as Henrietta Collins), Rollins cut his hair to military specs and formed the Rollins Band. The new outfit, made up of guitarist Chris Haskett, bassist Andrew Weiss, drummer Sim Cain and sound engineer Theo Van Rock, combined Black Flag's hardcore ferocity with mid-'70s metal and extemporaneous jazz. Recently, the Rollins Band garnered much attention as tourmates of Jane's Addiction. This new friendship eventually culminated into an opening spot on the first Lollapalooza Tour in 1992.

Now, Rollins is on the road promoting the band's major-label debut, The End of Silence, a seventy-minute examination of Rollins' misanthropy. The tour included two April shows at Medusa's and a spoken word performance at Lounge Ax in early May.

In December of 1991, Rollins witnessed the murder of his best friend, Joe Cole. The violence and anger which typify Rollins' lyrics had finally caught up with him.

He and Cole were headed home from a grocery store in Venice, California when they were held up by two armed men. After taking their money, the thieves forced Rollins to unlock the door to his house. As Henry finally reached the main hallway, Joe turned around and attempted to flee. Cole was shot in the face and Rollins escaped through a back entrance of the house. Images of the evening still haunt him.

"Sometimes when I catch myself having a really good time, or enjoying something," Rollins explains to art+performance, "I have a tendency to check myself and say, 'Should I really be grinning this much?'

"I'm not really all that experienced with death," says Rollins. "I wasn't in Vietnam. I know people who had everyone blown up next to them. I know people who killed more people than they can remember. I'm not bragging -- I'm saying I know people who REALLY know about death.

"I don't. I mean, I've only had ONE guy die next to me."

For several fateful moments, Rollins honestly thought he would never leave his house alive.

"It was strange -- being walked into your house at gunpoint -- because it wasn't like I didn't wonder if I was going to die. I knew I was going to be executed. I was terrified. But, in that time, there was something that was pretty unterrifying about it. It was very ultimate. . . If I said, 'Come on, man,' he'd say, 'Yeah, right. BANG ! ! !' I had a gun to my back and my hands up, and I went along. I didn't hope for the best. I couldn't hope."

After escaping and phoning the police, Rollins became the prime suspect in Joe Cole's murder. "I was arrested and held for ten hours, and since then they've been interrogating me as to how much cocaine we were moving out of the house. They're dealing with someone who's never even tried cocaine, never even really seen cocaine. So for me, trying to legitimize myself to this PIG, who's going, 'Come on, Henry, we're not trying to bust you. Just tell the truth. Are we talkin' kilos or what?' The guys don't get it. The strongest thing that came into our house was Tylenol and coffee. I'm totally a lightweight on that level."

Five months later, Rollins is unable to find any meaning in Joe's death. "You kill someone, they're dead. You step on a bug, you kill it, it's dead. That's it. You rot, make good soil for someone's tomato garden, and that's it.

"I don't believe in karma, I don't believe in any of that, because my friend died for nothing. I can't find a single reason why he died, except that someone shot him, and that's it. I mean, he came home from the store -- that's what he did. That's what we're guilty of -- coming back from the grocery store. That's what he did to die."

Rollins is still surprised by the unusual location of the murder.

"Venice is like one big small neighborhood," Rollins explains. "No one ever talks to each other but everyone knows who everyone is.

"There is an unwritten law in Venice. I lived on Brooks avenue, which bisects 5th and a big part of the middle of Venice called Ghost Town -- it's like Venice Shoreline Cryps. Crack, guns, dead bodies, helicopters, high-speed chases, but, if you're on the other side of 5th, you're not in Ghost Town. If you're not past 5th, you're not looking to buy drugs. They know that. And if you're in their neighborhood, you're in their neighborhood. . . It's really cool, because, if you want trouble, like you really ever would, but if you did, all you'd have to do is take ten steps over 5th, and all these black guys would be looking at you saying, 'Are you crazy??? Don't you know this is Ghost Town? Go ten steps back, or I'm gonna have to shoot you.'

"Me and Joe used to take our bikes and go through Ghost Town to go to the beach and work out on the chin-up bars. We used to call it Running the Gauntlet. You get all the speed you can for the two blocks before 5th, so by the time you get to Ghost Town, you're like hurling down, and there are guys trying to get in front of you to slow you down going 'Hey dude! Hey dude! Come here.' Yeah right. But the drag is, one night, Ghost Town came to visit. The guy who wasted Joe probably lived five blocks from my house.

"I basically lived in a hip ghetto. You go two blocks and to the left, and your in Baby Beirut. Back up, go two blocks and to the right, and you're at Dennis Hopper's house. Two blocks past that, and you're bumping your nose into Arnold Schwarzenegger's parking space at World Gym. Literally, Ghost Town ends at the end of Schwarzenegger's Jeep. Go two blocks from the Jeep, and I don't think even old Arnold would want to deal with that. They'd be like, 'Oh, yeah. Terminator, right??? BOOM!!!'"

"I moved the next day, because I didn't want them coming back and finishing me. I live in Hollywood now."

As Rollins puts his life back together, he has returned to the rigours of performing six nights a week. Unlike most artists, though, Rollins restricts himself to a highly militaristic regimen, working out for no less than 90 minutes before a concert.

As Rollins puts his life back together, he has returned to the rigours of performing six nights a week. Unlike most artists, though, Rollins restricts himself to a highly militaristic regimen, working out for no less than 90 minutes before a concert.

"Strong mind, strong body, until you have a total of one relationship with yourself. Mind, body, no separation. From that, I get my perspective -- touring is hard, but it's not as hard as trying to bench 210 pounds. . . It's a very Zen type thing. [By the time I reach the stage] I'm not thinking. I don't want to bring on the traffic jam and the other bullshit of the day. It's no place for that nonsense. No ego, no nothing. Bring the music. If you listen to any live Coltrane or live Miles records, that's what I hear. I hear a bunch of musicians only there for the music."

Rollins' daily priming before concerts helps reinforce his high level of discipline. "I don't do drugs, unless you call caffeine a drug. I drink coffee. I don't do any of that dangerous, intense shit. When I'm home, I write, I lift weights, I sleep, and I leave to go on tour. That's all I do. I eat Campbell's Soup and cheese sandwiches for dinner. I'm a very boring person. I don't have some kind of underworld life. I don't even drink."

However, Rollins innocently admits to one instance of exploratory curiosity. "I tried pot once. 1987. I got stoned with our bass player. He said, 'Here, why don't you try this.' OK. I tried it. Thought it sucked."

Even more unlike the majority of today's rock performers, Rollins doesn't even listen to contemporary music. "I listen to a lot of music," Rollins confesses, "but not many people on the records are alive anymore. Mostly jazz and blues, pretty much. If you came to my place and saw the music I listen to, you wouldn't even figure. You'd go, 'You listen to THIS and you play THAT?' It would surprise you. And I'm not talking about the Miles Davis, Mingus, or Coltrane thing. It's all those Boston records I have."

Rollins is by no means afraid to admit his disdain for much of today's alternative music scene. After a fan tossed him a present near the end of the first Medusa's concert, Rollins quipped, "Well. A leather baseball cap. How industrial!" He then mocked Wax Trax at its finest, screaming "Feel the bass! Feel the bass!" as the rest of the band hammered out a savage beat.

Rollins later explained, "That Chicago bullshit really is bullshit to me. I don't think that 'Get a beat box, program the seven o'clock news over it, and call it a twelve-inch and sell it to a bunch of drug addicts' thing is the thing I'm interested in. Though, they have the right to record it, I wish them all the luck in the world, I just won't be the one buying the record."

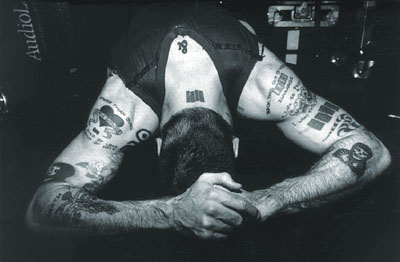

Swaying over the audience in nothing but ragged black running shorts, Henry Rollins screams, sweats and spits to the angst-ridden stylings of the Rollins Band.

For two hours the quartet mesmerizes the audience with its dark arrangements. As the band entwines distortion and jazz-like virtuosity, Rollins religiously wraps the extra microphone around his right hand. His body rocks back and forth while his left hand signals the audience to listen and listen good. As the band decreases its volume, Rollins recounts the images of Joe's death.

"No sir, oh sir, please, I don't want to die," he whimpers, the audience utterly silent. "Please sir, don't kill me."

The music suddenly explodes back into its Black Sabbath-like fury.

"Obscene! Ohhhhhh, so obscene!"

On some occasions, Rollins takes his intensity one step too far, as happened here in Chicago while touring with Black Flag. "That night at the [Cabaret] Metro, I got pulled off stage, got my clothes pulled off, kicked around a bit, and as I managed to get back on stage, pull my pants on, covered in blood and glass and cigarettes and spit, I just lost it. I had to be dragged, carried off stage.

"Just a bit of nervous exhaustion."

When Rollins isn't on the road with his bandmates, he manages his own publishing company, 2.13.61. Named after his birth date, the company releases literary works by Rollins and other less-recognized artists, such as Australian gothic rockster Nick Cave. Rollins has penned over a dozen books, and continues to constantly write while on tour. "We-do-more-before-nine-a.m.-than-most-people-do-all-day" Rollins is clearly a workaholic.

"I don't believe in spare time," Rollins notes proudly. "I don't take vacations, although I probably should. I was talking to this one guy who went to Costa Rica for a week and hiked. It sounded amazing -- monkeys, iguanas, birds, clouded forests. . . But, I know myself pretty well -- after about a day of that, I'd be going, 'Cool! Where's the fax machine? What do you mean I can't plug in? What the fuck is this?' I'm a city person, and I like shit that's open 24 hours."

Despite having recently removed the band from indie-label status, Rollins still prefers writing and touring over studio work. "By the time a record comes out, I'm bored with it. . . I'm interested in the new songs we haven't written yet.

"We would never dare go into the studio, write a song, record it, then release it. They have to cure -- they have to go out and get knocked around, the bolts have to fall out, and you gotta shake them until one part freezes up. . . They're like kids -- they keep yapping and moaning and bitching, so you have to go tend to them, check out where they're at, and help them along. They gotta get knocked around on the road, or otherwise we have no respect for them. Any song that can withstand 90 nights with us and still be a song, that's recordable."

Henry Rollins has transcended the typical rock hero, utilizing the intensity of Willard and the discipline of Kurtz. Brutal honesty and deep convictions have made him a unique and highly provocative addition to the '90s rock scene. Assuming Rollins never grants himself that occasional trip to Central America, how can he keep up the pace?

"Because I'm fucked up," Henry replies succinctly. "Not because I'm fucked up because I had too many Michelobs, or any Michelobs, for that matter. Different people have different motivations for doing music -- my thing has always been to vent myself. If it were money or women, I wouldn't be doing it like I'm doing it. I'm too smart.

"It's poor man's therapy," Rollins says. "It's almost a blues thing. If something makes you moan, you go out and howl."

Return to Andy's home page.

Return to the EdWeb home page.

EdWeb: Exploring Technology and School Reform, by Andy Carvin. All rights reserved.

card gamespuzzle gamessimulation gamespc gamesbrick bustermanagement games As Rollins puts his life back together, he has returned to the rigours of performing six nights a week. Unlike most artists, though, Rollins restricts himself to a highly militaristic regimen, working out for no less than 90 minutes before a concert.

As Rollins puts his life back together, he has returned to the rigours of performing six nights a week. Unlike most artists, though, Rollins restricts himself to a highly militaristic regimen, working out for no less than 90 minutes before a concert.