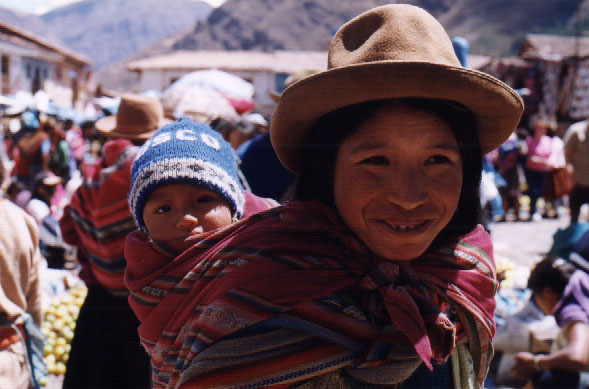

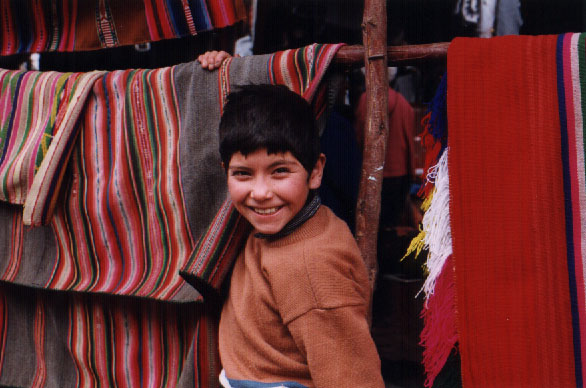

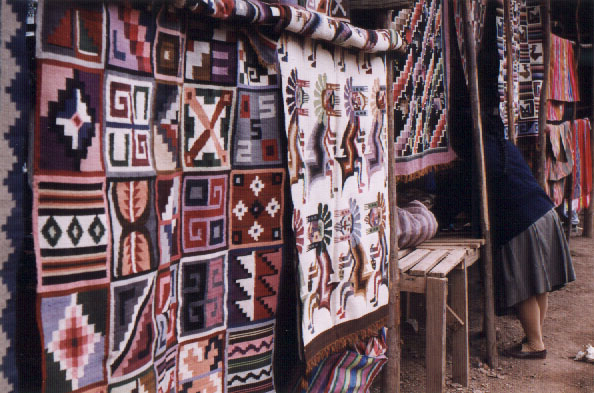

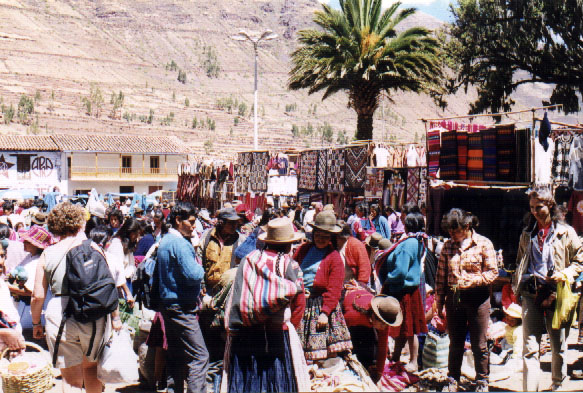

With less than 15 minutes until our appointed return to the bus I spotted Susanne entering the plaza. I quickly squeezed through the crowds to reach her. "Time is getting short," I said. "You've got to see this." Her excitement surpassed mine as she raised her camera, carefully selecting her subjects and executing each shot like a master assassin. Soon enough, though, our time had run out and we had little choice but to leave the market and return to the bus. I quickly purchased two pieces of freshly baked pitas from the bakery for 10 centavos each before we climbed aboard and departed Pisac.

The drive to the Inca fortress of Ollantaytambo was over an hour from Pisac so we broke for lunch in the village of Urubamba. Urubamba had apparently cornered the market for tour group lunch stops with practically every restaurant charging seven to 20 dollars for a fixed price, luke warm buffet. Nothing like reaping the benefits of a captive audience. The food was terrible by any standard save a tasty quinoa soup. Quinoa, an indigenous Andean grain with superlative nutritional qualities, had been a favorite of mine for several years so I had been looking forward to my first taste of it in South America. I've always prepared it like a rice dish but here it worked well in chicken soup. I also sampled a strange, dark purple pudding that tasted like nutmeg. A retired Peruvian couple explained to us it was a popular local dessert made from a dark blue corn. As Susanne and I tried to eat our meal, several restaurant employees walked the room stalking countless flies with swats from dirty rags. My appetite lessened with each frustrated swat.

|

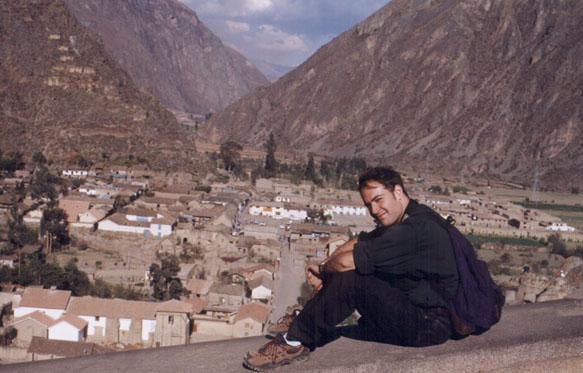

| Andy sitting atop the Ollantaytambo citadel |

After wasting away the hour in Urubamba we finally embarked for Ollantaytambo. Ollantaytambo is a massive citadel located at the confluence of three valleys, a scant 50 kilometers from Machu Picchu. The citadel served as both a temple and a fortress, the latter becoming of most importance upon the arrival of the Spanish. In 1536 Hernando Pizarro and his cavalry of 70 men attacked the citadel. Manco Inca, who had holed up his army at Ollantaytambo after the fall of Cusco and Sacsayhuaman, successfully halted Pizarro's initial siege as the Spanish horses were easily repelled by Inca warriors pelting them with rocks and arrows high atop the citadel's stone terraces. Pizarro retreated in humiliated defeat but Manco Inca's victory did not last; Spanish reinforcements eventually arrived and forced the Inca to retreat with his men further into the mountains, initiating the beginning of the end of Quechua rule in the valley.

|

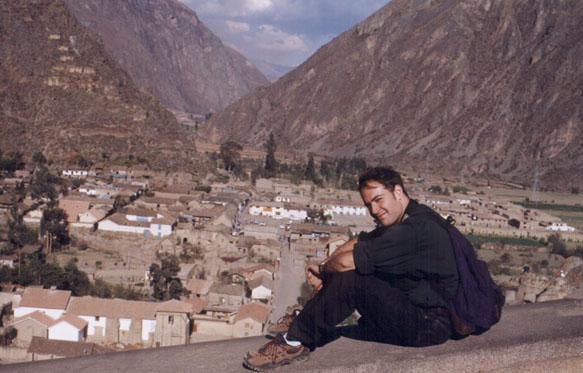

| Climbing to the top of Ollantaytambo |

Directly below the citadel's eastern slope sits the village of Ollantaytambo, a museum relic of a town if there ever was one. The local Quechuas continue to live in houses built by their Inca ancestors, using their ancient irrigation and plumbing systems as well. After squeezing tightly through the village's narrow cobblestone streets the bus reached the citadel. High along the mountainside I could see tiers of stone terraces climbing hundreds of feet into the air. Near the top I spotted a complex of immense stone blocks interlocked in a mystifyingly precise, typically Incan patterns. Our guide Alfred led us slowly up the main terraces. He pointed out that in times of peace Ollantaytambo served as a way station along the Inca highway system, with the three local valleys converging at this very point.

We climbed further up towards the massive stone walls. Huge granite blocks of 30 or 40 tons each were interlocked perfectly with no mortar or glue holding them together. The Inca empire possessed a lost art of stonemasonry in which they could maneuver multi-ton blocks, carve them into precise jigsaw-like pieces and fit them together, all without metal tools or even the wheel, let alone modern technology. Perhaps even more incredibly, all of these giant blocks were somehow transported from the mountainside ten kilometers away, across the valley and beyond the Urubamba River.

Because the Inca left no written records of their techniques scientists have hypothesized how the process might have worked. In terms of transporting the stones the Inca laid down an extended zigzag path from the quarry down the mountainside, allowing hundreds of men to drag the rocks with ropes, perhaps with the assistance of wood rollers or sled-like sliding beams. Some people have even suggested they may have diverted the Urubamba around the boulders, allowing them to drag the stones across the river without getting them stuck in the water. The masonry process might have worked like this: after carving the desired shape out of the first boulder and fitting it in place, the masons would somehow suspend the second boulder on scaffolding next to the first one. They would then have to trace out a pattern on the second boulder in order to plan the appropriate jigsaw shape that would fit the two together. In order to make a precise copy of the first boulder's edges, the masons might have used a straight stick with a hanging plumbob to trace its edges and mark off exact points for carving on the second boulder. After tracing out the pattern, they would sculpt the stone into shape, pounding it with hand-sized stones to get the general shape before using finger-size stones for precision sanding. Admittedly, this entire technique is merely scientific speculation. The method might have worked in practice but that doesn't mean this is how the ancient Quechua stonemasons did it. To me, though, our lack of knowing the truth only adds to my respect for this lost art.

Near the top of the citadel Alfred pointed out a huge lintel stone that he claimed weighs over 400 tons. I'm not sure how much of an exaggeration that might be, but I estimated its dimension being 20 feet by 10 feet by 10 feet, all solid granite. No matter its actual weight I can't but admire Incan tenacity for dragging this monolithic behemoth down and up the sides of the valley in order to position it at this very spot. Not far from the lintel stone we found the Temple of the Sun, a row of equally sized granite slabs separated by tall, thin sheets of rock. Five hundred years ago the Inca maintained this temple so that those slabs were covered in sheets of gold. "Gold was seen as the tears of the sun, just as silver was considered the tears of the moon," Alfred explained. When the sun rose in the east, the temple would face west and thus greet its creator each morning.

Before departing Ollantaytambo Susanne insisted we explore a series of stone watchtowers on a cliff high above the Temple of the Sun. I wasn't too thrilled with the prospects of climbing this precipice but I didn't care for the idea of Susanne going solo, either. Ignoring my fear of heights I followed her up the stone crags. In hindsight I admit it was a thrill to stand on the edge of a cliff with nothing protecting me but a two-foot wide, 500-year-old stone path; I just won't go looking for this sort of adventure on a daily basis.

The sun began to sink behind the mountainside as we returned to the bus and continued to the village of Chinchero, high atop the valley at 4000m. The temperature had dropped at least 30 degrees; Susanne and I donned our layers of sweatshirts and jackets before visiting Chinchero's modest, yet popular Quechua market. The market was much smaller than Pisac's, spread generously across Chinchero's Plaza de Armas, but it was also less touristed; apparently our group had the market to ourselves. As the sky darkened it was obvious the market was winding down for the evening, though the locals seemed happy to see us nonetheless. I was getting chilly at this point so I decided to shop for an alpaca scarf. I soon found a gray scarf for which one campesina was asking six soles, around two dollars. Ever eager to haggle, I offered two soles. The campesina laughed. We spent a minute or two haggling back and forth, both of us using broken Spanish. Eventually I convinced her to settle for three and a half soles, just over $1.15. We both seemed pleased with the outcome.

After visiting a small, dark chapel perched above the plaza Susanne and I rejoined our group on the bus before beginning the 45-minute drive to Cusco. At first I was a little wary at the thought of our bus careening down hairpin turns in the Andean darkness - "Busloads in India are killed this way," Susanne joked - but I was comforted by the appearance of stars high in the eastern sky. As I spotted three, then five, then a dozen stars glittering over the mountains I came to the modestly profound realization that this was the first time I had ever seen these particular stars. As a kid I used to love the night skies: I would pour over my astronomer's star charts before dragging my telescope outside in the wee hours of the morning, marveling at the crisp Florida sky. I knew exactly what stars would rise and fall depending on the time of year. But now I was in South America for the first time, eyeing the stars of the southern hemisphere for which I had no reference. I'd thought about this before coming to Peru but now it struck me that the world was so large there were entire constellations and galaxies I had never seen because I'd never gone so far south. I wondered where the Southern Cross was - my trip to the Andes wouldn't be complete without spotting it at least once.

Back in Cusco Susanne and I sat inside a dark café with a roaring fireplace. Most of the local cafes, including this one, were essentially all-day breakfast joints, but that suited us just fine. Our lousy lunch had killed our appetite for the day and we had munched on a roll of mint Mentos (the freshmaker) throughout the afternoon, so we ordered a light meal of yogurt with fresh fruit and muesli. It was a refreshing way to wrap up what had been a hectic, yet fascinating day.