|

| Andy overlooking Cusco's Plaza de Armas |

"Maté de coca, señor?" asked the smiling young campesina, brushing a jet black braid of hair over her right shoulder. "Sí, gracias," I replied, taking the tray from her hands and placing it on the glass table. It was late morning, around 11am; Susanne and I had just arrived in Cusco at the Hostal Loreto following a 12-hour trip from Washington DC to Peru. At over 10,000 feet in elevation Cusco is higher than any place I'd ever spent a significant length of time. I was leery of contracting a bad case of soroche,

brushing a jet black braid of hair over her right shoulder. "Sí, gracias," I replied, taking the tray from her hands and placing it on the glass table. It was late morning, around 11am; Susanne and I had just arrived in Cusco at the Hostal Loreto following a 12-hour trip from Washington DC to Peru. At over 10,000 feet in elevation Cusco is higher than any place I'd ever spent a significant length of time. I was leery of contracting a bad case of soroche, the severe altitude sickness common among gringos arriving here from the flatlands. Lucky for me, the local Quechua

the severe altitude sickness common among gringos arriving here from the flatlands. Lucky for me, the local Quechua indian descendants of the great Inca empire continue the tradition of offering weary travelers a cup of maté de coca - herbal coca tea - to help deaden the effects of two miles' elevation.

indian descendants of the great Inca empire continue the tradition of offering weary travelers a cup of maté de coca - herbal coca tea - to help deaden the effects of two miles' elevation.

Susanne and I sat on the second floor terrace of the colonial Hostal Loreto sipping our first tastes of maté de coca. Our visit to Peru was barely ten minutes old and I was already struck by the cultural differences between the US and the Andean highlands. At home this steaming cup of herbal tea would be considered contraband, despite its proven harmlessness, yet here in the Andes it is a custom of friendship and generosity to share coca, no different than inviting a neighbor in for coffee. I supposed such differences shouldn't surprise me, though; the mountains of Peru were a whole world away from my realm of experience.

Our visit to Peru was barely ten minutes old and I was already struck by the cultural differences between the US and the Andean highlands. At home this steaming cup of herbal tea would be considered contraband, despite its proven harmlessness, yet here in the Andes it is a custom of friendship and generosity to share coca, no different than inviting a neighbor in for coffee. I supposed such differences shouldn't surprise me, though; the mountains of Peru were a whole world away from my realm of experience.

The city of Cusco (also spelled as Cuzco, though the locals actually prefer the spelling Qosqo) is a living center of ancient Peruvian culture. According to legend Cusco was founded in the 12th century by the first Inca, Manco Capac. The word Inca, despite popular misconception, does not connote an ethnic tribe like the Cherokee or Lakota Sioux. The Inca was actually the royal dynastic line of a tribe of Quechua indians as well as the term used to describe its kings, just as Rome's emperors could be referred to as the caesars, or Russia's former kings as the tsars. As the ancient story goes, the gods sent Manco Capac to the earth, rising him out of the azure waters of Lake Titicaca. They gave him a divine rod with which he was to mark the spot for his capital city and proclaim as the home of his chosen people, the Quechua. When Manco Capac found the perfect spot - a beautiful valley high in the Andes - he planted the rod in the ground, designating the spot as the Navel of the Earth, or Qosqo in the Quechua language.

The legend of Manco Capac is a classic Andean legend, though the archaeological evidence suggests the Quechua weren't yet in control of the Cusco valley at that particular time. However, the 9th Inca, Pachacutec (pronounced Pacha Cootie), initiated a period of swift military expansion during which his armies captured much of the Andes from Columbia to Chile. By the 1430's Cusco became the capital of this new empire, Tawantinsuyu (the Four Corners), which were divided into the regions of Chinchaysuyu (the north and northwest), Kuntisuyo (the south and west), Kollasuyo (the south and southeast) and Antisuyo (the east), all of which radiated from the navel of the earth, Cusco. Tawantinsuyu and the Inca dynasty thrived for all but 100 years until the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors.

Images from El Primer Nueva Coronica y Buen Gobierno (1613-1615),

sketched by Quechua artist Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala.

Guaman's work is one of the earliest documentations of Andean life under the Spanish.

At first, Francisco Pizarro's small group of soldiers struggled against the Inca's armies until a civil war erupted after the death of Huayna Capac in 1532. Two of the Inca's sons fought over their right of ascension, dividing Tawantinsuyu into two rival kingdoms. Prince Huascar ruled his lands from Cusco while his half-brother Atahualpa ruled from Quito, the capital of the northern enclave of Chinchaysuyu. During the civil war Atahualpa defeated Huascar, killing him in at the battle of Huancavelica. When the Spaniards arrived two years later, Atahualpa Inca wrongly believed that Pizarro was actually the coming of Viracocha, a powerful god of Inca legend, and concluded that Viracocha had come to support him.

In what proved to be a most fateful move, Atahualpa agreed to meet with Pizarro at the stronghold of Cajamarca. Pizarro and his men ambushed the Inca and held him for ransom, demanding that an entire room be filled to the ceiling with gold and treasure. The Inca's people faithfully responded to the demand, gathering all the sacred relics of Chinchaysuyu in the ransom room. But when Pizarro got word that one of the Inca's armies was heading to Cajamarca he executed Atahualpa on the spot. This betrayal marked the end of indigenous rule of the Andes and the beginning of Spanish control. During the chaos that ensued Pizarro sacked Cusco, eventually capturing the capital. The Spanish looted the city, melting down its gold in a matter of weeks. They eventually took advantage of the Quechua's superb masonry skills and built their cathedrals and churches on top of Inca-period structures. This architectural blend of native and colonial elements remain in place to this day, making Cusco a historical gem of the Americas.

After finishing our matés we gathered our cameras and daypacks and headed for the Plaza de Armas, about ten paces from the Loreto's door. The Plaza de Armas is an immense public square that serves as the center of historic Cusco. While having a Plaza de Armas is common in towns throughout colonial Latin America, Cusco's plaza stands out because of the immense Inca foundations surrounding it. Buildings such as the Cusco cathedral, the Iglesia Compañia and even the Hostal Loreto are built on foundations of Inca masonry. Our room even has a 500-year-old Inca wall inside! The Plaza de Armas contains a central fountain, cobblestone paths and numerous benches surrounded by beds of flowers, making it a perfect spot for people watching. As soon as we stepped out into the plaza we were taken aback by Cusco's grandeur: a colonial town frozen in time with the Andes as its infinite backdrop. We were quickly hounded by boys offering to shine our shoes - well, Susanne's shoes actually, since mine weren't made of leather - as well as by older campesinas trying to sell us wool and souvenirs. But we hardly noticed them as we stood in the plaza, gazing in all four directions of the Inca's Tawantinsuyu, silently telling ourselves, "We're in the Andes now." No doubt about it.

|

Cusco's Plaza de Armas.

The Iglesia Compañia is in the center,

with the Hostal Loreto's entrance to its immediate left. |

As tempting as it was to break out our cameras - there were even llamas standing in front of the cathedral - we resisted the urge and opted for a rest at a local café. Susanne and I had little choice but to make our first day in Cusco a lazy one, since overexertion in the first hours of arrival at this altitude often leads to severe cases of soroche. We both carried a bottle of Diamox, an epilepsy drug also used for controlling altitude sickness (yet with the curious side effects of tingling extremities and a constant taste of iodine in the mouth). Still, if we rushed about all day we'd certainly be asking for trouble. To avoid the pounding headaches and nausea that accompany the illness we planned to do as little as possible today: drink tea, read and make travel arrangements to Machu Picchu - nothing more. Our first foray into prescribed inactivity began at the Plus Café, a precious little balcony restaurant with a perfect view of the cathedral and the Iglesia Compañia. Having quickly developed a taste for maté de coca (taste, mind you - this stuff isn't addictive) we both ordered two cups and some sesame rolls with jam. The day had become rather overcast so we continued to resist using the balcony for lots of pictures. I do, however, take advantage of the opportunity to test out my new 300mm telephoto lens which allowed me to get some great candid shots of local benchgoers. I couldn't' decide if I felt like a voyeur or a latter-day Jimmy Stewart in Rear Window. Either way I enjoyed it.

|

| Man on bench, Plaza de Armas |

After having our fill of rolls and maté we returned to the plaza and ambled along its perimeter, visiting shops and tour agencies. Susanne and I needed to make arrangements to get us to Machu Picchu this Tuesday as well as to find a good day tour of La Valle Sagrada del Incas - the Sacred Valley of the Incas, home to several notable villages and ruins along the Urubamba River. Most agencies offered Machu Picchu packages for $50 to $100, depending on the class of train service you wanted for the four hour ride to and from the ruins. Sacred Valley trips run from $7 to $70 depending on whether you want to go in a large group or on an exclusive private tour. One particular agency on the southern side of the plaza, La Compañia de Servicios Turisticos, seemed to stand out over the others. We told their senior tour guide, Luis Guillen, that we would get back to him by 6pm that night.

|

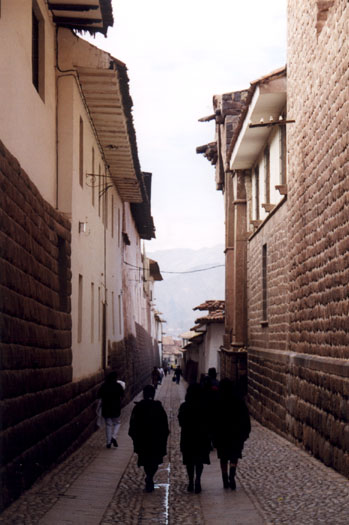

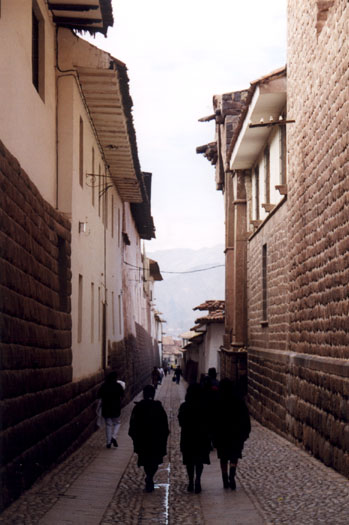

| Inca masonry, Calle Loreto |

Susanne and I then returned to the hotel for 30 minutes to relax and talk through our options. While we both would have preferred to hire a private car for our tour of the valley (as we had done in more affordable locales like Cairo and Delhi) it was clear that there were no bargains to be found in Cusco. Seven or seventy bucks, you get what you pay for. For both the valley tour and Machu Picchu we decided to deal with a larger tour group in order to save some money but we would spend a full three days at Machu Picchu in order to take in as much as possible by ourselves.

As we departed the hotel we walked east along the Calle Loreto towards a local crafts market. The entire street was walled with Inca masonry; I felt as if we were going back in time as we paced further down the ancient road, especially as we passed another campesina tending to her llama. But the Inca gods chose to frown upon us that afternoon as the skies opened up and rain fell hard on us. Rain in the middle of dry season? There was little we could do except get out of the showers; continuing to search for this craft market would not prove to be a wise solution. We concluded it would be best to save the mercado for another dry day - assuming every day in Cusco wasn't this damp. Susanne and I doubled back to the plaza in search of another round of maté.

Loreto towards a local crafts market. The entire street was walled with Inca masonry; I felt as if we were going back in time as we paced further down the ancient road, especially as we passed another campesina tending to her llama. But the Inca gods chose to frown upon us that afternoon as the skies opened up and rain fell hard on us. Rain in the middle of dry season? There was little we could do except get out of the showers; continuing to search for this craft market would not prove to be a wise solution. We concluded it would be best to save the mercado for another dry day - assuming every day in Cusco wasn't this damp. Susanne and I doubled back to the plaza in search of another round of maté.

As we approached the plaza we could hear the sounds of a brass band echoing down the stone walls of Calle Loreto. Across the plaza by the cathedral we spotted a procession of uniformed police and musicians carrying what appeared to be a statue of the Virgin Mary - or was it Santa Rosa de Lima? Today was her festival day in Lima. I immediately had a flashback to The Godfather, Part 2 - a somber procession carrying a statue of Mary through the crowded streets of Little Italy. Same idea, different script, I suppose.

|

| Santa Rosa de Lima procession into the Cusco Cathedral |

The rain now began to fall even harder so Susanne and I ducked for cover under a plaza archway where numerous children and campesinas were keeping dry. Following the archway we crossed over to the western perimeter of the plaza and climbed to the top of Café Kero, another popular balcony hangout. I relented and ordered hot chocolate while Susanne stuck to a reliable cup of maté de coca. We loitered there until 4pm when we decided to buy a pair to tourist ticket passes, which we would need to enter the major attractions in Cusco and the Sacred Valley. It should have been as simple as making a single stop at the local tourist office, but recent changes in the office's address coupled with schizophrenic business hours sent us on a wild goose chase in the drizzling rain. By our fourth stop we finally found a place to buy our passes: the Museo de Arte Religioso. As we left the museum we noticed our tickets had already been marked for entry into the museum - I guess the ticket man had assumed we planned to stay awhile.

Susanne and I briefly returned to the tour agency to book our tours of the Sacred Valley and Machu Picchu as well as our train tickets to the city of Puno, along the Peruvian side of Lake Titicaca. It was now past 5pm; I hadn't slept much on our overnight flight from New York to Lima so I was eager to get some supper and call it an evening. We ate dinner at D'Onofrio's, a pleasant enough Italian joint best known for its ice cream. We ate the lasagna and roasted chicken instead.

brushing a jet black braid of hair over her right shoulder. "Sí, gracias," I replied, taking the tray from her hands and placing it on the glass table. It was late morning, around 11am; Susanne and I had just arrived in Cusco at the Hostal Loreto following a 12-hour trip from Washington DC to Peru. At over 10,000 feet in elevation Cusco is higher than any place I'd ever spent a significant length of time. I was leery of contracting a bad case of soroche,

brushing a jet black braid of hair over her right shoulder. "Sí, gracias," I replied, taking the tray from her hands and placing it on the glass table. It was late morning, around 11am; Susanne and I had just arrived in Cusco at the Hostal Loreto following a 12-hour trip from Washington DC to Peru. At over 10,000 feet in elevation Cusco is higher than any place I'd ever spent a significant length of time. I was leery of contracting a bad case of soroche, the severe altitude sickness common among gringos arriving here from the flatlands. Lucky for me, the local Quechua

the severe altitude sickness common among gringos arriving here from the flatlands. Lucky for me, the local Quechua indian descendants of the great Inca empire continue the tradition of offering weary travelers a cup of maté de coca - herbal coca tea - to help deaden the effects of two miles' elevation.

indian descendants of the great Inca empire continue the tradition of offering weary travelers a cup of maté de coca - herbal coca tea - to help deaden the effects of two miles' elevation.  Our visit to Peru was barely ten minutes old and I was already struck by the cultural differences between the US and the Andean highlands. At home this steaming cup of herbal tea would be considered contraband, despite its proven harmlessness, yet here in the Andes it is a custom of friendship and generosity to share coca, no different than inviting a neighbor in for coffee. I supposed such differences shouldn't surprise me, though; the mountains of Peru were a whole world away from my realm of experience.

Our visit to Peru was barely ten minutes old and I was already struck by the cultural differences between the US and the Andean highlands. At home this steaming cup of herbal tea would be considered contraband, despite its proven harmlessness, yet here in the Andes it is a custom of friendship and generosity to share coca, no different than inviting a neighbor in for coffee. I supposed such differences shouldn't surprise me, though; the mountains of Peru were a whole world away from my realm of experience.