|

| Striking a pose at Machu Picchu |

I woke up to the sound of a cackling rooster just after 6am. Our alarm had gone off ten minutes earlier; Susanne must have hit the snooze button. We planned to catch the 7:30am bus up to Machu Picchu from Aguas Calientes, so we had until 6:30 to get up and then eat a quick breakfast at the hostal. I intended to sleep in a little later but the cock-a-doodle-doo's of the rooster cajoled me into getting out of bed.

In the hostal lobby the staff had set out bowls of fresh rolls and jam on wooden benches. I grabbed a table with a view of the TV, which was broadcasting the news in Spanish. Apparently a Swissair jet had crashed off Canada the day before; apart from that I couldn't understand the details. Susanne joined me around 6:45, with Angus coming downstairs a few minutes later. The hotel owner's daughter sat on a couch across from us, wrapping up her homework before hurrying off to school. It seemed no one was quite ready to get the day started as we peacefully sipped our coffee and maté de coca as the rooster outside wrapped up his morning routine.

Leaving the hotel soon after 7am, we walked downhill along Avenida Pachacutec stopping briefly at a shop to buy some bottled water. Each time we had walked by the shop yesterday the woman who owned the place would call out to us, "Agua sin gas? Papaya juice? Piña juice? Very good bananas..." The price of water was much lower down here in the village compared to the tourist-trap snack bar at the ruins, so I purchased two aguas sin gas while Angus picked up some fruit as well. He intended to climb Machu Picchu - the mountain, not the ruins - later that morning so he was stocking up on provisions. Since Susanne and I had no such intentions we figured two half-liter bottles of water was enough to get our day started.

At the small bus station along Aguas Calientes' train tracks I got in line to buy our round-trip bus tickets for the ruins. Francisco had mentioned to us the day before that you'd get a small discount on your second day's worth of bus tickets but the man behind the counter at the station seemed to be blissfully unaware of such discounts. I hoped this wouldn't be the case for entering Machu Picchu itself - supposedly the per-day entrance fee dropped from $10 to $5 after your first day - I guess we'd find out up top.

Susanne, Angus and I grabbed the last available seats on the 7:30 bus. I was a little concerned we might miss the bus due to a lack of seats, but as we boarded the bus we overheard someone say they were ready to send up a second bus if necessary. For the next 20 minutes we drove along the winding road, up and up the mountainside. Yesterday's ride was full of suspense - with each curve of the road I anticipated my first glimpse of Machu Picchu. Today, though, my anticipation turned into an overzealous spat of impatience as I anxiously awaited getting to the ruins before the trainloads of tourists arrived in three hours.

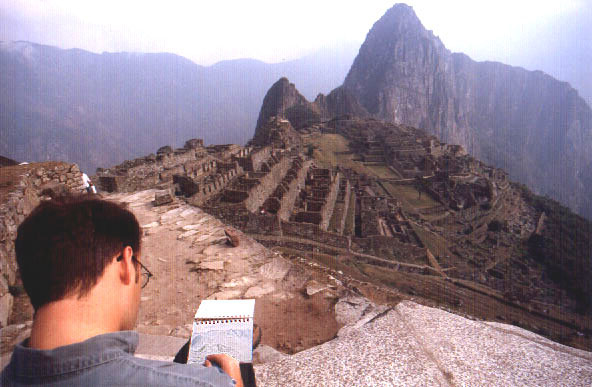

We entered Machu Picchu just before 8am - $5 dollars as promised by Francisco. Once again we smuggled water into the park, which seemed wise considering the morning was already heating up and becoming uncomfortably humid. Today we planned to spend as much time as possible inside the ruins. While we would have the entire morning tomorrow before catching the train back to Cusco, this was to be our only full day at the ruins, dawn 'til dusk. We really didn't have an agenda for the day, just some basic goals: take some classic "golden shot" photos of the ruins at different times of the day, revisit our favorite spots, perhaps sketch some pictures. Actually, I was quite excited at the prospect of drawing Machu Picchu. Though I've never been much of an artist, over the past several years I've sketched out some quick scenes in India, Nepal and Cambodia, and they came out better than expected. This year we decided to make an effort of capturing the sights on paper so we brought with us a small collection of sketch pads, color pencils, pastels, sharpeners and erasers. I had never attempted anything with pastels before but I was intrigued by the medium: unlike pens or pencils, pastels allow you to blend colors, to create abstractions, to emphasize mood over detail. Considering my biggest frustration in drawing has always been my utter inability to create details - people, architecture, etc. - I liked the idea of using pastels to create landscapes. I had no idea whether or not I'd be any good at it, but at least Machu Picchu gave me one hell of a first subject.

The sun hovered above the mountains to the northeast, the morning humidity creating a translucent haze in the air. Perhaps these weren't ideal conditions for photography but Susanne and I knew we only had so many opportunities to capture Machu Picchu on film. Our first goal was to climb up the terraces to just below the Caretaker's Hut to our self-proclaimed Golden Shot. Even though the light wasn't perfect the sun was still low enough on the horizon to create dramatic shadows - dramatic enough for my photos, anyway. We wound along the stone path we had discovered yesterday as being a shortcut to the spot. Though we were better acclimated to the altitude the walk wasn't any easier. "Even if we were doing this at sea level this climb would still be awful," Susanne commented. We were careful not to over-exert ourselves as we made our way upward - we had another day and a half of climbing here so we'd better get used to it.

|

| Susanne and Machu Picchu |

Within 10 or 15 minutes we made it to the lookout point. A large group of Israeli trekkers had just completed the grueling three-day Inca Trail and were resting near our favorite spot. For those folks brave enough to make the trek, the third day is the easiest, getting up early for the short walk around the side of Machu Picchu mountain before descending into the ruins. It was a strange sight watching exhausted backpackers making their way out of Machu Picchu just as we were getting our day started. The 20 or so Israelis looked beat, to say the least, many of them covered with the tell-tale blood blisters of black fly bites, though they clearly seemed ecstatic to have finally reached their end goal. If anything their presence served as a healthy reminder to us that trekking isn't a romantic romp across the hillside, and made me more pleased than ever that we chose to take the train instead.

The Israelis and their porters eventually exited the ruins, leaving the entire terrace to ourselves. Machu Picchu was deserted apart from the 50 or so tourists scattered throughout the ruins (compare that to the 1000 or so people who will be here after the late morning trains arrive). Susanne and I got comfortable on the terrace's boulders and began to take pictures. Susanne especially was well prepared for the moment, having hauled along her wide-angle lens and a variety of color filters to get the perfect shot. Further above us I could see our llama friends munching on the terrace grass. If we could only get them to move close to the edge of the terrace...

|

Andy catches his breath outside a stone house

|

After saturating our cameras with Golden Shot photos we slowly made our way down the terraces along a cobblestone path. The ruins just below the terraces are largely residential: modest homes of the lower-level priests and workers of Machu Picchu. Large stone door frames greeted us as we entered the houses, some of which were no larger than eight or ten feet square. We quickly descended even further down to the main plaza, several hundred feet below the Caretaker's Hut. Susanne and I couldn't decide where to go next so we started to scan the area to generate ideas. A moment or two later Susanne grabbed me by the arm and pointed upward. "Look!" she shouted. "The llamas are in our golden shot!"

Indeed, high above us, in the very place we had just left, two llamas stood at the edge of the highest terrace facing the ruins while a third actually made its way down the stone steps to a lower level. What nerve, I thought to myself - after all the effort we made to get them situated for the perfect photo, these woolly beasts were now mocking us by modeling themselves at the least opportune moment.

"We've got to get back up there now," Susanne insisted.

"You're crazy," I replied. "If we run up, we'll die before we get there, and if we take our time, the llamas will be back to hanging out in their pasture and we'll have missed the shot."

"I don't care," she responded. "We've got to try."

She was right, of course. We had talked about getting the most Golden of Golden Shots - a proud llama overlooking the ruins of Machu Picchu. Granted, the end product might be funny rather than powerful, but we still wanted to get the picture. Susanne and I turned upward and began the climb. It was difficult to pace ourselves; we wanted to get there as quickly as possible but each time we charged up a terrace or stairway we ended up hacking and wheezing to the point of almost seeing stars in our eyes. The higher we climbed the more skeptical I became: there's no way these animals are going to hang around for us, I thought to myself. But Susanne was determined. "We've got to keep going. This might be our only chance." Step by step, we retraced our way up the terraces until finally we reached the far end of the tier where we had taken our earlier photos. For whatever reason that day, Pachamama took mercy upon us and allowed us to get to the top before the llamas retreated. We would have our photograph - or at least the opportunity to give it our best shot.

In hindsight we could have taken our time getting to the top of the terraces - once we got there we realized these llamas weren't going anywhere any time soon. Nonetheless, we were both thrilled to find them there, despite our exhaustion and nausea. Our breathing and heart rates returned to normal as we took our time positioning ourselves behind the llamas. Not unlike yesterday, they appeared totally indifferent to our presence and to our strong desire to use them as photo models. These creatures certainly had minds of their own, but at this particular moment their minds told them to stand right here, right now and hang out.

"Say cheese," I said to one of them.

"Queso," I could almost hear it say back to me.

While the llama-chasing episode was well worth the pursuit, it sapped us of much of our energy. Susanne and I needed a carbohydrates boost, so we briefly left the ruins to purchase a couple of granola bars from the snack bar. Five soles each - I knew I should have packed some Nutragrain bars for the trip. While I walked off to use the men's room, Susanne bumped into Francisco, our guide from yesterday's tour. Francisco was glad to see we were sticking around the ruins for a couple of days.

"Are you going to climb Huayna Picchu," he asked, referring to the mountain behind the main ruins.

"No," Susanne replied, "not exactly."

"But you must climb Huayna Picchu," he insisted. "You're young and healthy. It'll be easy for you - less than two hours round trip. You may never come back to Machu Picchu. How can you not climb Huayna Picchu?"

Francisco's rhetoric worked wonders on Susanne, who was now ready to tackle the peak. I, on the other hand, initially resisted the idea, but as Susanne repeated Francisco's argument I soon realized they were both right. How could we not climb Huayna Picchu? I'm not very good when it comes to heights, but this was a chance to do something I'd be proud of for a long time - assuming I didn't slip off a precipice and fall 1500 feet to my death on razor-sharp rocky outcrops. It was now 11am, and if we wanted to make the climb we had to get started soon, for at 1pm they'd no longer allow people to make the ascent. Acrophobia be damned, I was ready to climb that rock.

We purchased a 1.5 liter bottle of water and smuggled it into the ruins. Once again I didn't feel great about breaking the no-water-bottle rule at Machu Picchu, but it seemed almost criminal to not allow intrepid climbers to bring along proper hydration. Fortunately no one ever seemed to want to search our bags each time we entered the ruins so there was no problem shlepping the water bottle along with us. Susanne and I made our way across the plaza to two small thatched huts that marked the entrance to Huayna Picchu. Beyond this point you had to sign in at a sentry's shack in order to let them know when you started your climb and, perhaps more importantly, if and when you make it back alive. We sat on a bench in one of the huts for a few minutes psyching ourselves up for the climb. "It's not difficult," I could hear Francisco say over and over again. We'd just have to find out for ourselves.

We signed in at the sentry's shack, where two sleepy guards sat around listening to a portable radio while ogling at girlie pinup calendars on the thatched walls. I looked at the sign-in book and saw an international list of climbers ahead of us: Australia, Holland, Yugoslavia, Israel, Russia were all represented. Most of them had just gotten started a little earlier than us (we signed in at 11:35), yet some of them had put down their names as early as 8:30am and had not signed out yet. Was this a sign of things to come?

|

The first of many steps up Huanya Picchu

|

The climb began with a slow descent down a flat stone path. "Why do we have to go down in order to go up?" I asked. "In order to make our final return as merciless as possible," Susanne responded. She was right - it may be nice to have an easy descent at the beginning of the hike, but two or three hours from now we'd be hating every last step upwards. The path continued its downward slope for several minutes, then curved upward again before making an even steeper drop down. We hadn't actually reached Huayna Picchu yet - we were beginning the climb on a smaller hill over which we'd have to go up and down before beginning the main ascent. The sandy path hung close to a steep edge that dropped off several hundred feet below. "If this is the bottom of the climb," I said, "I wonder how steep the drop would be from the top." Perhaps I really didn't want to know the answer to that question.

As we reached the knoll between the peaks and started our ascent, a group of four middle-aged Americans came down from ahead of us. "You're going to love it," one of them said, breathing hard. "Have a good time." Susanne and I looked at each other in mild despair. If this quartet of 50-somethings could make the climb so easily, we had no choice but to put up a good fight. With that thought in mind we began to go up.

Huayna Picchu isn't a technically difficult climb, you'll hear people say. That may be the case: we didn't need equipment to make the ascent, apart from our sturdy hiking boots. But this assurance didn't make our jobs any easier as we lumbered over jagged rocks and slippery sand, working higher and higher up the mountainside. Occasionally we would find rope handrails to help lead us along, but they always seemed to be placed arbitrarily, assisting us in one spot but ignoring our upward plight in another spot. We paused every 30 feet up or so to catch our breath for a few moments - perhaps 10 or 20 seconds each time - before tackling the next set of rocks. These breaks didn't prevent us from requiring superbreaks, though. With every five minutes of climbing we'd need at least one or two minutes of coughing, water chugging, cursing, and questioning of our sanity. "This will be worth it, this will be worth it," so the mantra went through our minds. Of course it would be worth it. "I can already tell that my appreciation for this climb will increase exponentially with each passing minute after we get back down and have a hamburger in my hands," I wheezed.

|

Andy putting on a brave face halfway up Huayna Picchu

|

As we climbed along we occasionally saw other people approaching us from behind. At first we said to each other we wouldn't allow anyone to pass us. Right. As the climbers got closer we could tell they were much more prepared for this than we were - intrepid climbers who probably spend half of the year in the Andes and the other half in the Himalayas walking up and down mountains. I didn't let it get to me as each person made their way up, reaching our location and eventually surpassing us. More power to them - this wasn't going to be a race. I just want to come down in once piece, not set a record pace.

About 45 minutes into the climb we encountered a pair of Australian women lowering themselves down a steep path with the assistance of one of the rope handrails. "Please tell us it's worth it," I begged them.

"It's worth it, don't worry," they said.

"How much further do we have to go?" I then asked.

"Oh, I'd guess you're about halfway up now. Just be sure to take a right when the path splits up ahead. It's a nicer view that way. Have fun..."

Halfway up?!? Did I hear that correctly? As slow as we were going I honestly thought we were making good time. Apparently this was going to be as rough as I had initially expected. We continued our pattern of climb-rest-climb-rest-rest-climb for the next 20 minutes, occasionally marveling at the incredible views beyond us. The ruins continued to get smaller and smaller with each step, just as the sharp precipice down to the main valley floor increased at a similar rate. Finally we began to see what appeared to be ruins of stone terracing above us. Indeed, the path ahead of us split in two directions: one steep path going up and to the left, and another, more tolerable path cutting far to the right around the edge of the mountain. We cut right and followed the path, leading us to a superb view of the entire valley. The ruins of Machu Picchu were perched peacefully down to our right, while the village of Aguas Calientes seemed so small and distant, half a mile straight down to our left. Linking these two images we could see the dusty bus path we took each time we went up and down the mountain, a winding snake that stretched up and down for miles. For the first time since our arrival at Machu Picchu we had a real overview of our surroundings. Even if our climb ended right here it would have been worth it, but we still had another 100 feet to go.

Susanne and I had been told that we would encounter some dark caves when we neared the top of Huayna Picchu. I had nearly forgotten about the caves until our counterclockwise path brought us to a series of large boulders in the shape of a mouth. We had nowhere to go but inside, so we arched our backs as low as possible and squeezed through the dark rocks. I pictured sacrificial Incan mummies lurking in the shadows but in reality I knew there were only abandoned water bottles to be found here. Exiting the other side of the cave the path continued to wind upward until we reached a second cave. Unfortunately this grotto had no apparent exit; while there were indeed several spaces to squeeze through they didn't seem to go upward. I poked myself between several boulders but each time found myself going nowhere.

Finally we noticed some light shining through some of the large rocks above us. I pulled myself up to see where it led and realized that the boulders themselves marked the top of Huayna Picchu. Squeezing through the rocks I saw a young Peruvian man in a dusty park ranger uniform sitting peacefully atop a large boulder. This must be the summit. We looked at each other and he motioned with his hand as if to say, "Yep, you've finally made it." I told Susanne this was where we should go, so we both squeezed through until we found ourselves propped atop these multi-ton boulders, each sitting precariously on the mountain's peak. We had finally conquered Huayna Picchu.

The view was truly spectacular, but it was difficult to experience the full 360 around you because each boulder was leaning at an angle, preventing you from standing up without the distinct possibility of falling to your death. I made myself as comfortable as I could and admired the scene before me. It was truly a marvelous experience to be sitting at the peak, but the better part of me kept saying to myself, "Let's get the hell off this thing." Susanne and I lingered for about 20 minutes before beginning our descent. It was now just after 1pm and the sun suspended itself high in the sky, baking us a little crisper with each passing minute. We were ready to return to stable ground.

|

Susanne along the Huanya Picchu path

|

The descent was much easier on our lungs in the sense that we didn't have to pause every other minute to catch our breath. This didn't mean there wasn't a tradeoff, though: the steep steps which were difficult to go up were now even more difficult to go down. "Incas must have had small feet," I said at one point. "I can't even get the side of my boot to fit on this step." Part of me wanted to rush down the mountainside as quickly as possible, but common sense told me that this would only lead to into a tumbling avalanche. We had to take our time. One great pleasure of going down, though, was watching people go up: exhausted and weary, several climbers passed us in the other directions as we cheered them on. "Only 20 minutes to go," I smiled devilishly. No wonder all the people we saw going down seemed happy to see us: each person going up served as a powerful reminder that the worst was over for us.

The last laugh went to the mountain, as I had earlier feared. In order to make the final exit we again had to descend to the knoll between the two peaks and then finish on an upward climb back to the sentry's shack. We probably had less than five minutes to go but again we were stuck pausing every 30 seconds, cursing the tectonic forces that made this place. "I have only two words for the managers of the Machu Picchu park," I said to Susanne: "Cog Railway." Sure, a comfortable ride in a rail car would have been all the easier for us to get up top, but as we made our final steps back to the sentry's post I scoffed at my own joke. Two and a half hours after we began, we had conquered Huayna Picchu. We stumbled into the thatched hut with the benches and collapsed.

"Assuming we don't die right here," I said, "I think it's time to head outside and get some food."

"Sounds good to me," Susanne said. We stood up, wiped the sweat off our faces and stumbled back to the park entrance, where overpriced junk food and swarms of stinging black flies would be our well-earned reward.

Down at the snack bar I spent 15 minutes scraping the grime off my fingers. The bathrooms here didn't have any soap so I had to rely on Susanne's collection of wet-wipes and a small bottle of Purel hand sanitizer. I transformed three wet-wipes into a dark, coalminer's black before I even bothered to use the sanitizer. There was no way I'd ever get my hands clean - the challenge, therefore, was to get then clean enough. Eventually hunger got the better of me and I purchased a greasy hamburger with ketchup and onions, which I held carefully under several layers of napkins as I ravenously consumed it.

Susanne, meanwhile, elected to sit in the shade over at the Machu Picchu Hotel restaurant. I told her I'd join her after I cleaned up the mess I had made with my wet-wipes and hamburger. After throwing away my trash I walked over towards the restaurant. A few feet to my left I passed a woman with long grayish hair sitting on a rock. She looked familiar to me, but I assumed I had just seen her on my tour the day before. I then noticed she was wearing a Chicago Field Museum t-shirt, which had me thinking that I knew her from my days at Northwestern.

When I got to the restaurant I began to tell Susanne about the woman. Just as I was about to tell her how familiar she seemed, my mind flashed back to the many education conferences I've attended over the years. The woman bore a striking resemblance to someone named Bonnie Thurber, who I've seen regularly at numerous conferences. I turned towards her and yelled out "Bonnie!" to see if she'd react. She immediately turned her head and looked at me, confused in a sort-of "Why do I know you?" way.

"Hi Bonnie, Andy Carvin. Long time no see."

"Andy!" she yelled. "Hi! What are you doing here?"

As it turned out Bonnie was in Peru for the Kidlink international educational conference and many of the attendees had opted to take an excursion to Machu Picchu. So here I was, high on a mountaintop in the middle of the Peruvian Andes, bumping into someone I usually saw at conference dinners. We talked for a little while, each relaying what we were doing in Peru. Susanne was finishing up her second round of granola bars so we eventually parted company, saying goodbye to Bonnie as we returned to the ruins. It really is a small world sometimes.

The crowds were thinning out so we decided to spend a little time wandering the stone house of the high priest and the Inca's residence. Unlike many of the other houses here which appear cobbled together, the royal houses were impeccably made with the sort of high precision stonemasonry you'd expect in an Inca structure. It was nice to get a look around without the throngs of visitors everywhere; when we visited the houses on yesterday's tour there must have been 30 of us jammed into the small room. Now we had the residence to ourselves and could marvel at its layout, including a separate bathroom. The Inca must have lived in style here.

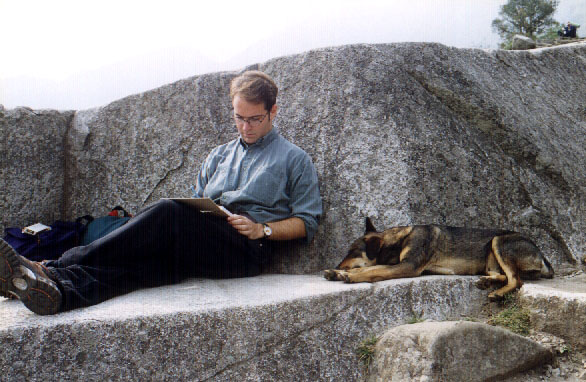

|

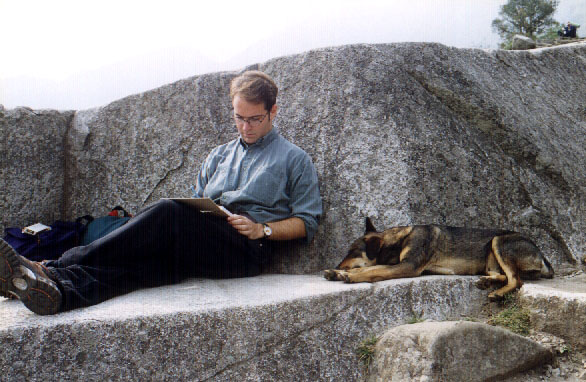

Andy sketches Machu Picchu with a bored art critic

|

By 3:00 or so we climbed once again to the terrace below the caretaker's hut for our favorite view of the ruins. This time, though, instead of whipping out our cameras we got comfortable and found our drawing supplies. We had plenty of time to kill, so we sat there for about an hour sketching the scene before us. My pastels were a bit of a challenge at first but I became adept at blending colors with my fingertips, appointing each finger to work with a given color as to not accidentally blend the wrong hues together. As I sat there a dog appeared out of nowhere and settled next to me. It was a strange sight, as if we had brought our pet with us and he was now patiently waiting for us to wrap up our work. At one point a group of tourists climbed the terrace and settled directly above us to admire the view. I overheard one of them say to another, "Look, honey, artists!" I couldn't believe they were actually applying that label to me, considering my complete and utter lack of skills, but I nonetheless enjoyed the compliment.

4:30 came and went so we packed up our supplies and headed down to the entrance to catch the last bus to Aguas Calientes. We had considered staying later than 5pm to watch the sun set and then walk the six kilometers back to town, but after having conquered Huayna Picchu earlier that day we were ready to call it a night. Not long after our bus began its descent we approached a young Indian boy waiting by the edge of the road. As we passed him he waved his right arm and shouted what sounded like, "Oooh-paaaah!" He must be saying hello, I figured. A few minutes later we turned a curve, reaching further down the mountain, and there he was again, just ahead of us, yelling "Oooh-paaaah!" Apparently he was racing us down the mountain. With each curve down the cliff the entire bus anticipated his appearance. Like clockwork, he was waiting for us with another "Oooh-paaaah!" As soon as we would pass him he'd race to a steep set of stairs that would allow him to take a shortcut and get ahead of us.

After seven or eight Oooh-paaaah's we reached the bottom of the cliff. The boy, of course, was ahead of us once again, and now waved down the bus to catch a ride into town and collect whatever tips he could. The bus crowd gave him a round of applause as he climbed on board and gave us a final Oooh-paaaah. Susanne and I looked at each other, both impressed with such a clever way to make money. His method was most successful; many people on the bus handed him one dollar bills for his effort. Assuming he made the trip only a couple times a day, and with 30 or 40 people per bus, there's a good chance he was making a lot more money than his parents. Not a bad racket.

|

Blankets for sale, Aguas Calientes

|

Our Canadian friend Angus was on the bus as well, so we joined him for the walk up to the Hostal Cabaña. Angus apparently spent the morning climbing Machu Picchu mountain, so we compared notes as he noted his plan to climb Huayna Picchu as well the next day. One mountain was enough for us but we wished him good luck. Angus said he'd be going to a pizza restaurant called Chez Maggie later that night and invited us to join him. We told him we'd swing by in an hour or two. Back at the hotel we climbed up to our new room on the fourth floor (hotel management asked us to switch rooms because a group needed a block of rooms, including our triple). The room had a nice view of the village and what appeared to be a large avocado tree growing just outside, but for some odd reason there was a large piece of wood missing from the bathroom door. It didn't seem to be an accident; from the cut of the hole it appeared to be an artistic decision that just so happened to eliminate any chance of bathroom privacy. We'd have to get around to asking the management about that.

Susanne and I both showered and cleaned up before meeting Angus at Chez Maggie, about 100 feet below the hostal on the sloping avenida leading back to the center of town. We had the place to ourselves and sat across from a smoky adobe wood oven. Angus had arrived early so his pizza arrived a few minutes after we did. It smelled delicious so we ordered the same: a large Hawaiian pizza with garlic bread. Our pizza appeared 30 minutes later, piping hot with two bowls of sauces. "This one is a creamy garlic sauce, and it's not bad," Angus said. "But be careful with the other one. It's got a bit of a bite." I immediately spread the hot sauce all over my first slice and sighed as the taste buds exploded in my mouth. Meanwhile, our waiter came by and showed us a map book for tourists he had designed on his computer. The atlas was an incredible piece of work, both in terms of its artistry and in the amount of useful information each map provided. He'll probably do well once he's ready to sell them.

We lingered at Chez Maggie for a while, talking about Angus' experience living in Chile as well as Canadian stereotypes of Americans versus American stereotypes of Canadians. It was quite the politically incorrect conversation - a perfect chat over pizza and beer, right? Back at the hotel Susanne and I got organized for the next morning. We'd have four or five hours at the ruins before we would need to catch the afternoon train back to Cusco. Our long day at Machu Picchu had been a draining experience, but I already knew it would be hard to leave this mystical place.