|

| Machu Picchu |

I must have gotten that one hour of sleep last night: Susanne had to wake me after our alarm went off at 4:45am. We had a long day ahead of us - after a bumpy four-hour train ride to Aguas Calientes we'd have a two-hour tour of Machu Picchu around 11 o'clock. Only after 1pm or so would we have time to ourselves. My stomach still ached from dinner at the Inka Grill; I hoped I wouldn't get sick on the train. My lack of sleep at least almost made me too tired to be nauseous, so I packed up my things and hoped the morning would go smoothly.

At 5:45am we stood outside with the manager of our hotel, who was kind enough to make sure we got off to the train station alright. By 6am there was still no sign of Luis but then a large bus pulled up in front of the hotel. The manager urged us to get inside. "Dónde está Luis?" I asked. He replied in Spanish, but Susanne and I both got the sense that Luis had telephoned earlier and said he wouldn't be available today. Assuming this was the case, we climbed into the bus. As we drove away from the plaza a woman inside the bus began to call out a list of names. Our names, to our chagrin, were not among them. We looked at our hotel manager friend, who had thankfully joined us for the ride, and he examined the list, confirming our worst fears. He and the woman conferred for a moment, trying to figure out what to do with us. He then turned to me and said in broken English, "Which Luis? Hotel Luis?" Uh oh, there was a Luis who worked at the Loreto. "No," I replied, "Luis Guillen." "Luis Guillen!" he laughed. " Okay, no problem." I wasn't sure what he was going to do to help us but I kept my fingers crossed.

The train station was a chaotic scene of tourists, police, travel agents and last-minute food sellers. The hotel manager grabbed me by the arm and said, "Follow me, señor." As we entered the main part of the station he began to shout "Cecilia! Cecilia!" Within a few seconds a woman with a handful of tickets waved at him and motioned for us to come over. They talked for a moment while she shuffled through the tickets. "Su-sahn Cornwáll?" she asked. The woman had found our tickets, which included our train reservations, day passes to Machu Picchu, bus transfers and a hotel voucher. Somehow everything had fallen into place despite all the confusion. We graciously thanked our hotel friend before boarding the tourist train to Machu Picchu.

The orange and yellow narrow-gauge train carried four passenger cars, each seating around 30 people. Even though we were traveling in Pullman class - a full step above regular first class - conditions were cramped as each pair of seats faced another pair, leaving little leg room for any of us. Two young Chilean women were seated directly in front of us. At 6:25 the train departed exactly on time. There were many empty seats in our car - perhaps more people would get on at Ollantaytambo in two hours. Until then at least we could spread out and get comfortable. Despite my lack of sleep and stomach pains I felt well enough to enjoy the complimentary meal of cheese sandwiches and maté de coca. Susanne slept like a log.

The first half hour of the ride was comprised of an arduous series of switchbacks. In order for the train to ascend Cusco's steep valley it zigzagged left and right, switching tracks a total of four times before the train was able to continue straight along a single track. Once we were out of the Cusco area the train slowly descended into the Sacred Valley in order to hug the Urubamba River for the rest of the four hour journey. Because the train was on a narrow gauge line we bounced and bobbled like an amusement ride the entire way. Once you got used to the rolling the train trip was quite enjoyable. The scenery along the Urubamba was reminiscent of southern Colorado: thick red clay, sagebrush, cacti and agave plants, boulders the size of houses.

Across the river the valley rose upward into steep, green hills, often covered with tiers of evenly spaced farming terraces. This valley was the breadbasket of the Inca empire. It amazed me to think that after 500 years these same terraces were still being used by the Inca's Quechua descendants. Along the hillside I could also occasionally see a faint gravel line cutting across the terraces at different angles. This was the remnant of the Inca highway that linked Cusco with Machu Picchu by way of Ollantaytambo. The entire trek would usually take seven days for the Inca to complete. At regular intervals along the trail were huaman - rest houses for weary travelers not unlike the caravansarai of the ancient Silk Road. Most of the huaman have long vanished but every now and then I could spot the ruins of one. We passed such a ruin just as we entered Ollantaytambo to pick up more passengers. A large group of German trekkers got on board and filled every available seat, forcing us back to our original assigned spots.

By 10am the train had descended to around 2300 meters. What had once looked like the Old West turned into Disney's Jungle Cruise - lush, dense forest, jungle plants, high levels of humidity. We were now in the transition zone between the Andes and the Amazon basin. We were getting close to Machu Picchu - I could taste it. We pulled into Aguas Calientes station at 10:30. The train used to stop at the Puentes Ruinas station, two kilometers further, but landslides courtesy of El Niño obstructed the track up ahead. About 50 of us were under the charge of Willie, a Peruvian tour guide with gold teeth whose every other sentenced always seemed to be "My name is Willie." As we gathered at the station Willie said there was time to use the restrooms before we caught the bus to Machu Picchu. Many people heeded his suggestion and went for the toilets but less than 30 seconds later Willie yelled, "Okay, we go to the buses now," and started to walk the rest of the group to town. This struck me as extremely rude, leaving so many people abandoned in the lavatories. Willie was now on my bad side as far as I was concerned.

|

| Aguas Calientes |

The bus terminal was in the heart of Aguas Calientes, a quaint jungle outpost that was booming from all the tourist activity. We didn't have time to drop our bags at the hotel so we lugged them onto the bus with a plan to check them at the ruins. The bus drove down a gravel road until reaching the bottom of a steep mountainside. We then proceeded to curve slowly up an S-shaped road in order to ascend the 1500-foot peak. With each turn the anticipation grew, the suspense reaching a fever pitch as we climbed high into the clouds. Just before we reached the top I could see stone terraces and ruins of what appeared to be houses hanging over the edge of the mountain. This must be it - Machu Picchu, one of the most mysterious places on earth.

The bus pulled into a dusty parking lot next to what appeared to be a large motel with an open air restaurant: the Puentes Ruinas Hotel. We had considered staying here until we discovered the $200/night price tag. Willie gathered up the group and announced that we would split up into two tours, one in English and one in Spanish. Thank God - a bilingual tour of this size would have been intolerable. Willie introduced his friend Pancho, a tall, thin mestizo whose mannerisms bore an eerie resemblance to the British actor Tim Roth. Pancho reintroduced himself as Francisco (only his friends called him Pancho, I guess) and said he would lead the English tour. His English was layered with a strong accent but he seemed to have a powerful grasp of grammar and vocabulary. I wondered where he learned to speak it so well.

Once we entered the gates we followed a sandy path along the edge of a cliff and eventually climbed a stone passage that continued to curve around the size of the precipice. The scene soon unfolded before us: we were now standing in front of Machu Picchu, the greatest archeological ruins of the Americas. Ahead of me I could see a series of stone terraces and houses in neat rows, with additional ruins high above on a small hill. A large grassy plaza occupied the center of the ruins. And behind all of this soared a jagged, mystical mountaintop: Huayna Picchu, perhaps the most extraordinary backdrop of any ruins on earth. "This was the habitation, this is the site," Pablo Neruda wrote of this very image in his epic Heights of Machu Picchu:

This was the habitation, this is the site:

here the fat grains of maize grew high

to fall like red hail.

The fleece of the vicuña was carded here

to clothe men's loves in gold, their tombs and mothers,

the king, the prayers, the warriors....

This was the habitation, this is the site, and now I am here. I am in awe.

While the members of our group snapped pictures like paparazzi, Francisco began to explain the origins of the ruins. "In front of you," he said, "you can see a mountain. This is Huayna Picchu, or Young Peak. Behind us there is another mountain: Machu Picchu, or Old Peak. Do not ask me if the ruins are named for the mountain or if the mountain is named after the ruins. We do not know. As you will see over the next two hours there is much we do not know about the ruins of Machu Picchu..."

Francisco was right on target - so much of our knowledge of Machu Picchu is based on guesswork instead of evidence. The one thing we do know for sure is that it was rediscovered by explorer (and later senator) Hiram Bingham on July 24, 1911. Bingham, a Yale professor of Latin American history, had received funding from the university and the National Geographic Society to find Villcabamba, the lost Inca fortress believed to have been built down the Urubamba River after the fall of the citadel at Ollantaytambo. After weeks of trekking downriver Bingham met an old Quechua campesino and asked him if he knew of Villcabamba. The campesino replied he had never heard of it, but he'd be happy to tell him about Machu Picchu instead. Intrigued, Bingham paid the old man one sole to take him to this Machu Picchu. After an arduous climb up a steep mountain Bingham found a series of ruins covered in dense jungle. As he cut away the growth it seemed the ruins kept going further and further along the mountainside. At last, Bingham concluded, he had found the lost Villcabamba. After clearing the ruins and taking thousands of photographs, Bingham reintroduced the world to Machu Picchu through a special issue of National Geographic.

"This is where the truth ends," Francisco noted, for practically everything else you usually hear about Machu Picchu is mere speculation. For example, current theory suggests that Machu Picchu was probably a religious retreat for the Inca. Hiram Bingham, thanks to his clouded Villcabamba obsession, was convinced the ruins were a military stronghold, describing much of the site in military terms. Archaeologists also now believe that Machu Picchu may have been built by the Inca Pachacutec in the early 15th century, and that it had probably fallen out of use by the time of the Spanish Conquest. Again, it's difficult to be sure because the Inca civilization left no written records and there's no evidence the Spanish ever learned of Machu Picchu's existence.

I seem to hear that a lot - people saying how amazed they are that the Spanish never found this place. To be honest, this doesn't surprise me at all. What surprises me is that the Inca ever found this place and had the gumption to make it into a permanent settlement. Machu Picchu sits high atop a mountain peak with a sheer cliff drop on two sides. It's near the Amazon in a climate far more temperate than the Quechua were used to high up in the Andes. Put perhaps that's exactly why the Inca built Machu Picchu - if I were a ruler of western South America and was looking for a religious retreat far away from both my friends and enemies, Machu Picchu is the perfect spot. Its giant terraces support a variety of crops and offer plenty of room for wool-generating alpacas, vicuñas and llamas to graze. The high mountaintops provide a natural clean water source that continues to run today - Francisco pointed out a series of cascading fountains carved into the living rock of the hillside. The Inca channeled intricate waterways that controlled flow and allowed for the separation of sediment. Machu Picchu is one with the mountain, one with its surroundings - indeed a magical and holy place any royal Inca would have appreciated.

"If you want to see what the people of Machu Picchu produced, go to Connecticut," Francisco continued. "That's where all the relics are now. If you want to see pictures of Machu Picchu, read National Geographic. But if you really want to understand the magic of Machu Picchu and what this mountain meant to the Inca, stay right here for a week and you'll see. Better yet, stay one month, maybe two or three. You can only understand Machu Picchu by experiencing it for yourself."

If you read the books, watched the documentaries, all you'd be left with would be a series of disconnected, contradictory impressions. Machu Picchu feels more like a natural park that an archaeological site, for so many of the temples and structures here were carved out of the living rock: caves, hillsides and streams metamorphosed into homes and temples. To me it seemed the Inca created Machu Picchu as a celebration of nature, a celebration of life.

|

| Francisco, our Machu Picchu Guide |

Francisco brought us to a small house with high quality masonry, the type you might see in and around Cusco. "This was perhaps the residence of the high priest, or even of the Inca himself when he made the seven-day journey from Cusco," he explained. "The other houses here are strong and sturdy but here the walls are perfect. Nothing less than perfect would be acceptable for the Inca." Connected to the main room were a bathroom and two side rooms - amenities fit for royalty. On the floor the stone surface had been carved low and rounded until it was in the shape of a mortar. Perhaps the high priest once created ritual powders here.

We climbed up through the ruins of a residential area before reaching a stone quarry full of huge boulders. "As you can see there is enough rock here to keep the Inca building at Machu Picchu for a long time," Francisco pointed out. "Why did they stop? Again, we don't know." Below the quarry's edge lay a large boulder that appeared to have been cut in half. "A scientist several years ago wanted to test a theory as to how the Inca cut large stones," our guide continued. "After chiseling a line of evenly spaced holes with a piece of rock, he filled the holes with wood jammed in by a stone mallet. The wood was wet, and wet wood expands. In a short amount of time the scientists split the boulder in two. So you can see it does not take magic or magnetism or aliens to build Machu Picchu. To say such things insults memory of the intelligent people who built it."

Francisco's comments had a healthy tinge of skepticism. He seemed to be troubled by any supernatural or paranormal explanation of how Machu Picchu came to be. Near the Temple of Three Windows, so called for its three identical portals, Francisco said, "There are a lot of people now who believe this place holds mystical powers. They pay $200 to come here as part of a special mystical tour of the ruins. You see, it is said there are magnetic channels running through the earth connecting Machu Picchu with Kathmandu, in the Himalayas. So some people come here and chant their mantras, to become one with themselves or something like that. You see, over here there are niches in the wall that were once used to hold sacred items. But to the mystics, they've become places where you can chant and feel the vibrations around you. Try this..." Francisco then proceeded to stick his head in a niche and droned in a low tone, "Omm.... Omm..." The sound resonated across the plaza along with our laughter. "See? I feel better now that all my sacred chakras are in alignment. Now you know. I just saved each of you two hundred dollars..."

Adjacent to the Temple of the Three Doors we found a small botanical garden. "Here you can see what the Inca grew at Machu Picchu," Francisco explained. "Avocado, papaya, coca - these were all very important. What the Inca didn't have, though, is grass. Look around you - all the grass you see here didn't come to the Americas until after the Spanish. It's not native. Try to picture Machu Picchu without it and you'll have an idea of what it once looked like."

|

Intihuatana, the Hitching Post of the Sun.

In the background you can see the mountain Huayna Picchu,

the Caretaker's Hut and stone terraces. |

Francisco led us atop a small hill containing several stone plazas. In one corner sat a peculiar carved rock, one that I recognized immediately. "This is Intihuatana, the Hitching Post of the Sun," Francisco said. "To Hiram Bingham and his fellow scientists it was simply a sundial. A sundial! Only an American would come up with such a small scale of time - time is so important to you Americans, right? The Intihuatana was a clock of the universe. It's precisely aligned with the points of the compass so that the high priests could calculate solstices, equinoxes, the cycles of the seasons. High priest, chief astronomer - there was probably little difference at Machu Picchu."

We descended the hill behind Intihuatana and crossed the grassy plaza to a pair of thatched roof huts. "These huts are the start and end of your climb to the top of Huayna Picchu," Francisco said. "There is no time to climb it today - it is an hour or so each way - but if you spend the night here I would highly recommend it." I looked at Susanne and said, "Forget it."

She seemed surprised. "I had already convinced myself to climb it since I assumed you'd insist on trying it."

"Hell no," I replied. "Not with my fear of heights."

I could hear Francisco explain to someone, "Oh, it's not difficult; just be careful as you go around each precipice. It's a steep drop..." That sealed it. There was no way I was climbing that rock, no matter how sacred it was.

We again crossed the plaza towards the house of the high priest. "This we call the Cave of the Condor," Francisco explained. "Several mummies have been found inside. The reason we call it the Cave of the Condor is carved below you. The triangle shape is the body of a Condor. The circle above it is its eye. The small triangle next to the circle is its beak. And the entrance to the cave is its wings." It was a wonderfully abstract concept; who knew if it was intended, but I hoped he was correct.

"And now for some caving adventure," Francisco smiled. "Watch your heads." We squeezed through the cave to a set of steps that led to a new group of ruins. "Hiram Bingham called this the Prison Group. Again, this shows us his bias." Because Bingham was convinced he had found the Villcabamba fortress, his perspective caused him to assume these rooms were prison cells. "Take a look at the niches in the walls," Francisco continued. "They were probably used for holding gold statues. But watch this..." He climbed into the niche and squatted inside, sticking his hands through what appeared to be holes for wood support beams. "What does this look like to you, from your American or European perspective?" Francisco asked. "A colonial stockade!" The Quechua of South America had no such concept of a public jail. Hiram Bingham judged the culture from his own historical perspective. This building was no jail. You see this everywhere. Tour books refer to one building as the Sacristy. Sacristy is a Christian concept. The Inca would have no idea what that meant."

We exited the so-called Prison Group as Francisco wrapped up the tour. "I now pronounce you as condors. You are free to fly away and explore Machu Picchu by yourself." Francisco was certainly one of the best guides I've ever met. He had an immense knowledge of the history of Andean culture as well as the healthy skepticism of a anthropologist. Susanne talked with him as we exited the ruins for lunch. Apparently he learned his English in Cusco and had practiced it as a guide, he told Susanne. We thanked him again as he headed off to guide another tour. I'm glad we got a chance to meet him, as brief as it was.

For lunch I ate at the hotel buffet - a $15 a plate feast of cold soup, cold vegetables, stale bread, and unidentifiable meat. I would not make the same mistake twice. Susanne wisely munched on a pack of biscuits and a coke from the snack bar. We re-entered the ruins around 2pm, just as most visitors were departing for the afternoon train. The majority of Machu Picchu's visitors come on day trips from Cusco. Because of the length of the train ride each way they only have three or four hours to see the ruins. By 4pm, Machu Picchu is supposedly deserted. I hoped we'd have the park to ourselves now.

Once making our way along the cliff path entrance we tried to trace Francisco's original entry route by climbing a small flight of stone steps. The steps then diverged in two directions; we were pretty sure Francisco had taken us to the right, but we were overtaken with the urge to explore some new ground and go left. We quickly regretted that decision. The path rose at an increasing rate in the form of a zigzag path. Because of the thick scrub on both sides of the walkway we couldn't see where we were going. Meanwhile the steepness of the walk and the high elevation caused us to huff and puff, pausing every few meters to catch our breath. "This better be worth it," said Susanne, sputtering for oxygen. The path eventually flattened and the bushes thinned. I could hear two or three voices ahead of us. Suddenly I realized where we were: Susanne and I had ascended Machu Picchu's grassy terraces from behind and were now just below what's known as the Caretaker's Hut. This could only mean one thing: we were about to encounter one of the greatest views on earth.

And there it was, the entire field of ruins dotting the landscape with the glorious peak of Huayna Picchu rising from behind. This was the "golden shot" - the place where all photographers seek out that classic picture of Machu Picchu. On the terraces above us I could see several large rocks and boulders that looked stable enough to sit on, including one boulder that had a wedge cut out in the shape of a bench. Someone was sitting on the bench so we climbed to the terrace and leaned on a smaller rock, our feet dangling over the edge of the terrace.

"This is why we came here," Susanne said.

"I know I say this every time we go somewhere amazing," I replied, "but I can't believe we're actually here. I mean, I knew we'd get to Machu Picchu eventually, but this place is so out of the way I never figured we'd see it this soon."

We sat awhile on the terrace, admiring our golden view of Machu Picchu. Susanne brought several filters and a wide angle lens for her camera, so she experimented with a variety a photos. I climbed higher to a spot next to the Caretaker's Hut, a stone house that was recently re-thatched after a fire last year to show people what it might have looked like in Inca times. My camera didn't have as wide a lens as Susanne's did so I had to keep going up further to fit the entire scene in my camera window. I then climbed beyond the hut to take a shot with our panoramic camera. As I looked at the terraces beyond the hut I noticed several llamas grazing in the grass.

"Susanne!" I yelled. "Llamas!"

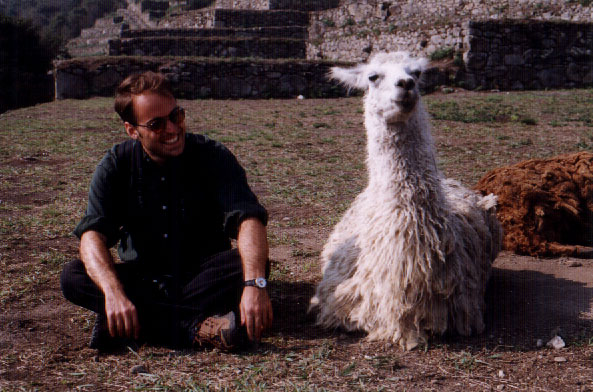

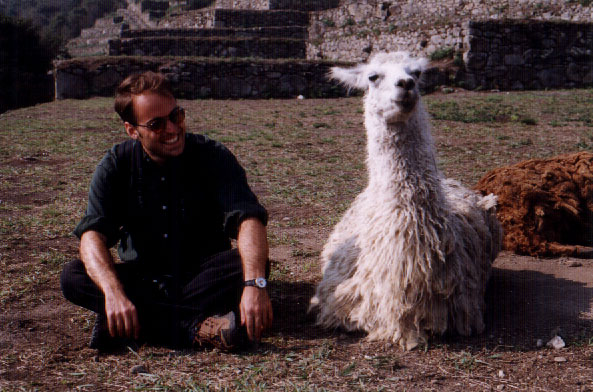

She quickly mounted the terraces to see my discovery. Three llamas, one pure white, one brown and another white with dark spots were noshing on grass and weeds a few yards away. A fourth llama, also brown, was much further away on a higher terrace. I cautiously approached the spotted llama, which we affectionately called Aesthetic Llama since it looked like a postcard perfect llama. (We considered naming them Panchen Llama, Llama Dorje and Dalai Llama but decided against it in deference to the plight of Tibetans.) The llama didn't seem to mind me getting closer or even petting it. In fact it didn't seem interested in even acknowledging my presence. Eating grass, apparently, was clearly higher a priority than worry about privacy-invading gringos. Susanne and I took some pictures of us with the llama. We then wondered if we could get them to stand by the edge of the terrace and pose for a shot with the rest of Machu Picchu. "Haven't you heard the expression 'as difficult as herding llamas?'" I asked. Susanne laughed. "Of course not," I continued. "I just wonder if there would be any truth to it."

|

At first we tried yelling, "Hey llama, over here." We then snapped our fingers, whistled at them, even gave them a polite tap on the rump, but each time they would either sit there or walk away in the wrong direction. This truly was as difficult as herding llamas. Having accepted defeat I sat next to the white llama, who was now squatting in the sand, soaking up the sun. I scratched its neck for a while until it made a high- pitched "Mmm" sound. I had never heard llamas before so the sound caught me off guard. As I stared at it in amazement the llama whined again. Susanne and I burst out laughing. The llama didn't sound angry or scared - perhaps a little annoyed or bored, though. The next thing I knew, the llama belly rolled to the right, landing right on top of me. As I fell over in shock the camelid got up and walked away. Apparently the llama decided to use me to boost it back up. Nothing like feeling useful.

Susanne and I watched the llamas for a few more minutes, hoping one of the would wander over to a better spot. "Green grass!" Susanne said. "Yummy grass! Come over here - please!" She pleaded to no avail. This clearly wasn't going to work. Eventually we bid the llamas goodbye and moved on. We descended a stone pathway, passing through ruined houses and temples. Not far from the main plaza Susanne climbed down to a grassy terrace and made got comfortable. I soon joined her; there we sat, staring at the ruins, staring at Huayna Picchu, staring at the misty peaks beyond. There's no greater pleasure at Machu Picchu than staring at your surroundings and wondering.

Just before 4:30pm I suggested we return to the bus and check into our hotel. The last bus for Aguas Calientes departed at 5 o'clock but I was pretty exhausted from our full day, early wakeup and all-night insomnia. Susanne didn't seem thrilled with the idea of leaving until the last possible bus but I convinced her my body was about to give out on me.

I should have heeded Susanne's wishes. After exiting the ruins we discovered that the 4:30 bus had left early and we were now stuck waiting for the 5 o'clock bus after all. They wouldn't let us on the bus just yet so we had to stand about as hundreds of tiny black flies swarmed around our faces. Fortunately we had brought an ample supply of bug repellent - there were dozens of travelers here pock marked by the black fly's evil blood blisters. Around 4:55 we boarded the bus and began the 20-minute descent down the mountain. As the village of Aguas Calientes appeared to grow with our approach I thought about our day's visit and was gratified we had two more days to explore the ruins. It makes no sense why anyone would spend only four hours here after coming so far. Francisco was right - you'd need months to fully appreciate the magic of this place. Hopefully another two days inside the ruins would give me more than just a shallow glimpse.

|

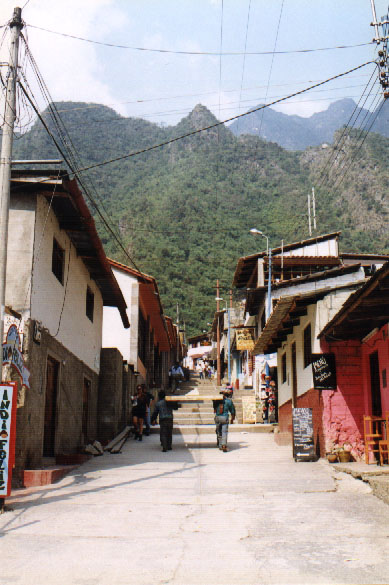

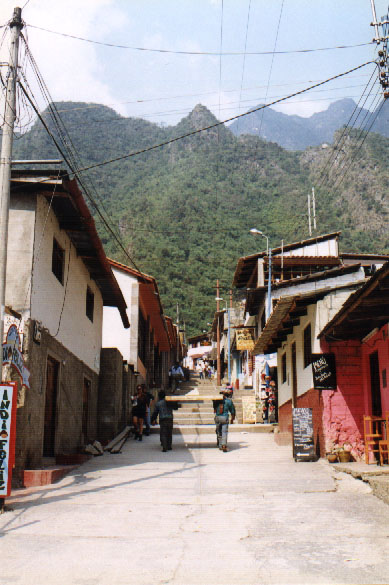

Heading toward Hostal Cabaña, Aguas Calientes

|

We exited the bus in Aguas Calientes and attempted to get our bearings. I knew the Hostal Cabaña was a 10-minute walk from the bus station - but in which direction? I then overheard a blonde man ask in Spanish, "Dónde está Hostal Cabaña?" Once he got directions I asked him if we could tag along. His name was Angus and he was a Canadian who had worked for a mining company in Chile. He had just left his job and was now traveling around before returning to Toronto. We crossed the village's small Plaza de Armas and hung a right, reaching a long pedestrian street heading up a moderately steep hill. La Cabaña, to our chagrin, was near the top of the hill. As we struggled upward, children played in the street, rolling toy trucks down its slope. Open air restaurants invited us in with the smells of pizza, hamburgers and fries - the staples of the trekker's diet. I didn't like the idea of having to climb this hill each time we returned from the ruins but at least this was the only time we'd be lugging a lot of weight upward.

After passing a brightly decorated eatery, the Manu Restaurant, we found the Hostal Cabaña on our left. At first we couldn't track down anyone working there but a few minutes a short Mestizo woman came running down the stairs. I handed her our voucher and asked, "Tiene un doble con bano privado?" "Yes," she replied in English. "You have a reservation, yes? My name is Martha. Please follow me." Angus, Susanne and I trailed her through the building, walking out back to what appeared to be a new three story building. This must be the new addition to the hotel, I thought. Martha gave us a spacious triple on the second floor before taking Angus further upstairs. "Tonight you can have this triple," she said, "but tomorrow I will have to move you." We offered to take a double tonight but she explained there were none available. The triple would be just fine. As Angus went upstairs he said he planned to go to the Manu for dinner. "Maybe we'll see you over there, then." I said.

Susanne and I relaxed for awhile and cleaned up before walking next door to the restaurant. There were plenty of tables available outside, so we sat out front, ordering some matés and an egg sandwich. Susanne wasn't too hungry so she ate some of her leftover biscuits purchased at the Machu Picchu snack shop. A few minutes later Angus appeared so we invited him to join us. He ordered a trout platter and a bottle of Cusqueño beer. We sat around and chatted as the sky darkened, bringing a slight chill in the air. One of the young boys playing by street came over to the table and poked her head up by Susanne, staring at her shyly. "Hola," Susanne said, offering him a cracker. He took it from her hands, shoving it in his mouth as he went back to play. A few minutes later he returned, eager for another snack. In between visits a small dog also appeared, cautiously approaching the table. Susanne tried offering it a cracker as well but the dog jumped back nervously. Eventually it leaned forward and took the cracker.

By 7:30 or so I felt like I was going to fall over and collapse, so we said goodbye to Angus, who stuck around for a second beer. Back at the hotel I dropped to the bed, having no desire to get back up until tomorrow morning. Today was as grueling as I had expected, but well worth every ache and every yawn. Our adventure at Machu Picchu was just beginning.