4:45am, and it's black as pitch outside, yet we've got no choice but to get out of bed. Our morning flight to Siem Reap had been changed from 7:30 to 6:30, which meant we'd have to ride through the streets of Phnom Penh before sunrise. Just a day or two before, I was nervous about the prospects of a pre-dawn drive through Phnom Penh. Bandits, corrupt cops, hottentots, we'd inevitably be kidnapped and sold for scrap. Now, of course, I realized that this was an absurd overreaction on my part. At 5:30am, the streets of Phnom Penh seemed safer than Washington DC would have been at the same time. Just don't let the cabby take any short cuts down some hidden alleyways, I grimaced.

We rode along the quiet treelined boulevards and reached the airport in about 15 minutes. Susanne and I picked up our boarding passes, paid the $10 departure tax and waited for boarding as two large groups of German and Japanese tourists crowded the departure lounge. They looked well traveled, sporting Saigon and Luang Prabang t-shirts. Susanne talked with a woman from Manchester, England who had spent two months alone wandering the South Pacific, Burma and Vietnam before coming to Cambodia. Meanwhile I worried we'd get hassled because of the size of our backpacks - there was a 10 kilogram per passenger limit on baggage, and I'm sure our packs exceeded the limited, but no one asked us anything except "carry-on bags?"

The sun rose at 6am, not long before we boarded the flight. Before the July coup there were seven flights a day to Siem Reap. Now there were only three, and until the end of the rains last week, they were largely empty. Our flight had about 40 people on board, more than half full. We munched on angel cake muffins and coffee during the brief 35 minute flight. I had hoped for a stunning view of Angkor on the way down, but instead had to settle for rice paddies, stilt houses and the occasional humble wat.

on the way down, but instead had to settle for rice paddies, stilt houses and the occasional humble wat.

Siem Reap is perhaps the smallest airport I've ever seen, even beating Connecticut's New Haven airport. A few steps inside and we were already at the exit, as two dozen or so frenzied taxi drivers waited outside ready to pounce on unsuspecting tourists. We too would have to choose a driver from amongst this crowd, so we paused for a second, put on our game faces and then opened the door to face the music. All 20 cabbies charged us, shouting "Siem Reap! Siem Reap! Angkor! I will drive!" About six or seven of them pressed into me and pawed at my hands and shirt. It was time to choose, so I decided to grab the smallest guy I could find - that way, if he proved to be a difficult person, I'd look all the more intimidating to him. Maybe. I looked at a small, smiling young man to my left and said, "You! Golden Apsara Guesthouse." He charged forward, as did the other drivers - apparently they could all get a commission from this particular hotel. I asked him how much the ride would cost, to which he responded, "Free ride - courtesy service to Golden Apsara." I suppose his commission would surpass the price of the cab ride. "OK, let's go." We pushed through the crowd, caught a breath of fresh Cambodian country air, and climbed into the little man's Camry. Another young Khmer, this one grinning even more than the first man, closed our doors and got into the driver's seat. We started the short ride into Siem Reap, the only major town around Angkor.

Guesthouse." He charged forward, as did the other drivers - apparently they could all get a commission from this particular hotel. I asked him how much the ride would cost, to which he responded, "Free ride - courtesy service to Golden Apsara." I suppose his commission would surpass the price of the cab ride. "OK, let's go." We pushed through the crowd, caught a breath of fresh Cambodian country air, and climbed into the little man's Camry. Another young Khmer, this one grinning even more than the first man, closed our doors and got into the driver's seat. We started the short ride into Siem Reap, the only major town around Angkor.

The driver didn't talk much, but the first man told us a bit about the area. The town had about 70,000 residents but it felt much smaller to me, like a pleasant country village where everyone knew everyone else and exchanged gossip over Tiger beer and Mild Sevens cigarettes at the local garden cafe. The only traffic was the occasional motorscooter or young boy herding the family cattle down the road. The first man asked if we wanted a driver for our stay. "He will drive you - his name is Rang," he said, pointing to the driver, who repeated "Rang," smiling cheerfully. "20 dollars a day." This was the going rate in town, so we agreed to use him as our escort for our stay. We arrived at the hotel, a quaint villa in need of a fresh whitewash, but quite nice by our flexible accommodation standards. The owner, an older gentleman who spoke fluent French but no English, showed us a large room with three beds, ceiling fan, a refrigerator, bathroom and a spotless floor, $20 dollars a day. Fair enough. We gladly dropped our backpacks to the beds.

Susanne and I changed clothes and prepared our film supply for the day while Rang arranged our two day passes to Angkor for $40 each (the passes would have been good for a third day if we'd had the time). $40 may seem rather steep compared to practically every other entrance fee in Asia, but considering that here were the greatest archeological ruins on earth and one of the few steady sources of hard currency for this poor country, $40 seemed a small price to pay. Rang returned about 20 minutes later. He still had that large grin on his face, as if her were excited for us, this being our first visit to the famed ruins of Angkor.

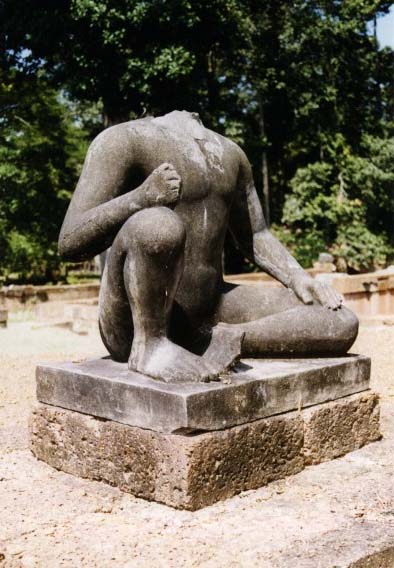

From the 9th to the 15th centuries, the Khmer kingdom at Angkor was the most powerful and architecturally prodigious culture in southeast Asia. The Khmers had lived for centuries in this region, which had earlier been known as Funan and Chenla, but they were often dominated by the regional superpowers of the time, namely China to the north and Java to the south. In 802 a Khmer official in the Javanese court returned to his homeland, declared himself the god-king Jayavarman II and decried full independence from Java. Jayavarman II became the first of many god-kings of the Khmer court at Angkor. As god-kings, Jayavarman and his successors commissioned stone temples to themselves as well as to the Hindu god Shiva, often patterning the structures into a three-tiered representation of Mt. Meru

and decried full independence from Java. Jayavarman II became the first of many god-kings of the Khmer court at Angkor. As god-kings, Jayavarman and his successors commissioned stone temples to themselves as well as to the Hindu god Shiva, often patterning the structures into a three-tiered representation of Mt. Meru , the mythical centerpoint of time and space. By around 880 CE, the monarch Indravarman became the first god-king to construct massive irrigation works that allowed Angkor to expand in size and population.

, the mythical centerpoint of time and space. By around 880 CE, the monarch Indravarman became the first god-king to construct massive irrigation works that allowed Angkor to expand in size and population.

The next three centuries would see a series of political waves fluctuating between growth and decline. Angkor reached its first peak with the ascension of Suryavarman II in 1112, who expanded the kingdom into Vietnam and Thailand and built the famed Shiva temple of Angkor Wat. Yet the southern Vietnamese state of Champa would not be subjugated. In 1177, the Chams initiated a covert counterattack, quietly sailing up the great lake of central Cambodia, the Tonle Sap. Within a few years, the Chams sacked Angkor and executed the king, but the Khmers immediately regrouped for an attempt to take back Angkor. A cousin of the former king led the charge, retaking Angkor around 1180. He was eventually crowned as Jayavarman VII . For the next four decades, this Jayavarman would reign through Angkor's greatest period.

. For the next four decades, this Jayavarman would reign through Angkor's greatest period.

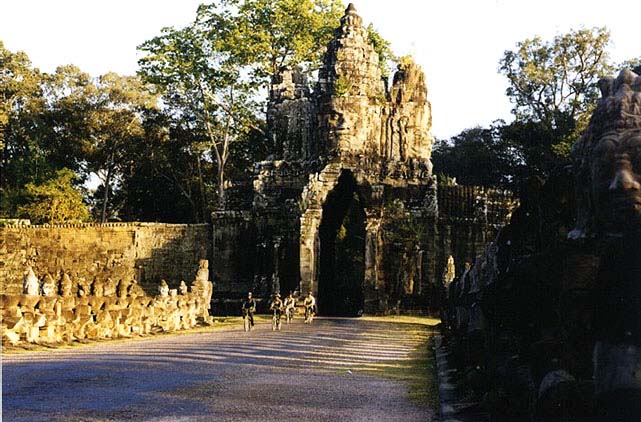

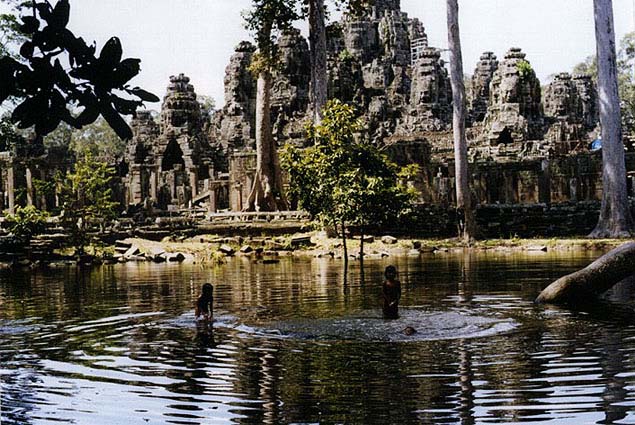

Jayavarman VII is best known for constructing Angkor Thom, the nine-square-kilometer walled city that would serve as the royal capital for 400 years. Jayavarman VII commissioned the Baphuon Palace as well as the Bayon, famous for its scores of smirking stone faces. On the cultural front, Jayavarman VII officially converted the state religion from Hinduism to Buddhism, though the conversion process had been going on in Khmer communities for some time. Instead of constructing monuments to Shiva and Vishnu, Jayavarman VII glorified images of the Buddha and his incarnation as Avelokitesvara . Jayavarman VII's reign was the pinnacle of Khmer culture, and after his death things began to slip away. By the 15th and 16th centuries the Thai kingdom of Ayutthaya was in ascendance, and after several half-hearted attempts at destroying the Khmers they sacked Angkor in 1431 and 1594, eventually ending its term as Khmer capital. The Khmers eventually regrouped in their new capital at Phnom Penh, many miles away to the south of the Tonle Sap, but the glory period of Khmer history was over.

. Jayavarman VII's reign was the pinnacle of Khmer culture, and after his death things began to slip away. By the 15th and 16th centuries the Thai kingdom of Ayutthaya was in ascendance, and after several half-hearted attempts at destroying the Khmers they sacked Angkor in 1431 and 1594, eventually ending its term as Khmer capital. The Khmers eventually regrouped in their new capital at Phnom Penh, many miles away to the south of the Tonle Sap, but the glory period of Khmer history was over.

Angkor was not known in the west until it was "discovered" by French explorers in the mid 19th century. They brought home tales of adventure - as well as unbelievable etchings of Angkor itself - back to an eager French public. Through the turn of the century to the 1960's Angkor was a popular spot for globetrotting European Asiaphiles, but civil war in 1970 and the Khmer Rouge takeover in 1975 made Angkor and surrounding Siem Reap province a rebel hotspot. Khmer Rouge cadre buried thousands of landmines in and around Angkor, occasionally kidnapping and killing tourists as well. As recent as 1995, Dr. Susan Hadden of the Alliance for Public Technology was killed in a bandit ambush near the grand ruins of Banteay Srei, just north of Angkor. I didn't know Dr. Hadden well, but we had emailed each other on numerous occasions in the summer of 1994 while I was constructing my EdWeb website. Her death at Banteay Srei was a chilling reminder that even with the end of the fighting and a strong UN presence, Siem Reap province was still a dangerous place.

With this long history of glory, intrigue and murder in my mind, we were now in a car passing the entry checkpoint into Angkor. The checkpoint consisted of a small roadside kiosk where several bored policemen sat around while a smiling woman checked visitor passes. We drove north until reaching a T in the road. We turned left and continued along a wide body of water that Rang pointed out to us to be the moat of Angkor Wat. The moat was over a mile long on this side and at least 500 feet wide. But on the other side of the water, all I could see was forest, dense and lush from the recent monsoon rains. Somewhere within this verdant island fortress was Angkor Wat. I eagerly awaited my first sight of it.

We hooked a right and hugged the left-hand side of the moat, again heading north. As we approached the moat's western causeway I finally saw the five stupa-like towers of Angkor Wat. Even with this passing glimpse I was awestruck, perhaps less with what I saw and rather because I was so amazed that I was even here in the first place. But before I could have any sort of metaphysical epiphany, we whizzed by Angkor Wat, heading north towards the walled city of Angkor Thom. The greatest temple on earth would have to wait, and I would have to settle with only a teasing taste of it. Angkor Wat vanished behind us, again shrouded by its dense forest cape. I had always envisioned Angkor to be a massive open expanse of monuments, like the pyramids of Giza or the central plain of Chichen Itza in Mexico, but much of Angkor was separated by miles of trees and swamp land. Angkor wasn't a single archeological site - it was an entire city preserved by centuries of outside ignorance of its existence.

on the way down, but instead had to settle for rice paddies, stilt houses and the occasional humble wat.

on the way down, but instead had to settle for rice paddies, stilt houses and the occasional humble wat.  Guesthouse." He charged forward, as did the other drivers - apparently they could all get a commission from this particular hotel. I asked him how much the ride would cost, to which he responded, "Free ride - courtesy service to Golden Apsara." I suppose his commission would surpass the price of the cab ride. "OK, let's go." We pushed through the crowd, caught a breath of fresh Cambodian country air, and climbed into the little man's Camry. Another young Khmer, this one grinning even more than the first man, closed our doors and got into the driver's seat. We started the short ride into Siem Reap, the only major town around Angkor.

Guesthouse." He charged forward, as did the other drivers - apparently they could all get a commission from this particular hotel. I asked him how much the ride would cost, to which he responded, "Free ride - courtesy service to Golden Apsara." I suppose his commission would surpass the price of the cab ride. "OK, let's go." We pushed through the crowd, caught a breath of fresh Cambodian country air, and climbed into the little man's Camry. Another young Khmer, this one grinning even more than the first man, closed our doors and got into the driver's seat. We started the short ride into Siem Reap, the only major town around Angkor.

and decried full independence from Java. Jayavarman II became the first of many god-kings of the Khmer court at Angkor. As god-kings, Jayavarman and his successors commissioned stone temples to themselves as well as to the Hindu god Shiva, often patterning the structures into a three-tiered representation of Mt. Meru

and decried full independence from Java. Jayavarman II became the first of many god-kings of the Khmer court at Angkor. As god-kings, Jayavarman and his successors commissioned stone temples to themselves as well as to the Hindu god Shiva, often patterning the structures into a three-tiered representation of Mt. Meru , the mythical centerpoint of time and space. By around 880 CE, the monarch Indravarman became the first god-king to construct massive irrigation works that allowed Angkor to expand in size and population.

, the mythical centerpoint of time and space. By around 880 CE, the monarch Indravarman became the first god-king to construct massive irrigation works that allowed Angkor to expand in size and population.  . For the next four decades, this Jayavarman would reign through Angkor's greatest period.

. For the next four decades, this Jayavarman would reign through Angkor's greatest period.  . Jayavarman VII's reign was the pinnacle of Khmer culture, and after his death things began to slip away. By the 15th and 16th centuries the Thai kingdom of Ayutthaya was in ascendance, and after several half-hearted attempts at destroying the Khmers they sacked Angkor in 1431 and 1594, eventually ending its term as Khmer capital. The Khmers eventually regrouped in their new capital at Phnom Penh, many miles away to the south of the Tonle Sap, but the glory period of Khmer history was over.

. Jayavarman VII's reign was the pinnacle of Khmer culture, and after his death things began to slip away. By the 15th and 16th centuries the Thai kingdom of Ayutthaya was in ascendance, and after several half-hearted attempts at destroying the Khmers they sacked Angkor in 1431 and 1594, eventually ending its term as Khmer capital. The Khmers eventually regrouped in their new capital at Phnom Penh, many miles away to the south of the Tonle Sap, but the glory period of Khmer history was over.