Tuesday, November 12:

Tuesday, November 12:4:30am. God, I didn't want to get up. Of course, if we missed the Shatabdhi Express train to Agra at 6:15am, our plans would be severely tripped up. We needed to get to Agra early enough to see all of the major sites, catch a ride of some kind to Mathura, the home of the Hare Krishna movement, and then hop on the overnight train to Varanasi at 8:55pm. It was gonna be a tight schedule. We took no chances and got to the New Delhi Railway Station by 5:45 or so. The train arrived at six, and left promptly with us securely on board. I talked with a few Brits who had been to India and Agra before, and they seemed confident that we could accomplish all of our day's plans and still have enough time to catch our train from Mathura.

The Agra Cantonnment Station - I had been told that this was the most dangerous train station in India, at least in terms of getting robbed or ripped off. Despite this reputation, we felt that we were clearly in control of the situation. Now we just had to check our backpacks in storage, find a tour that was suitable to our needs, and get started with the day. Baggage check was a breeze at the left luggage facility - nice and bureaucratic, with lots of paperwork - I felt at ease that our bags would survive the day there. We then started to talk to the man at the inquiry counter, but I couldn't understand a word of his English. I then saw another westerner, a man in his mid- to late 20s, with a big backpack in hand. We struck up a conversation quickly - his name was Philip, he was a computer programmer from Boulder, and he had been in India for about as long as we had. We decided that three's company would provide us with better leverage in organizing a private tour, so we checked his bag and prepared ourselves for walking the gauntlet of tourguides, touts, and pickpockets.

We were soon approached by a group of men. One of them said, "Let us be your guide - fixed prices, set by the Agra government, we promise, no problem..." He handed me a laminated card off of the inquiry desk counter - a private tour of the Taj Mahal, the Agra Fort, and Fatehpur Sikri would be 550 rupees for all three of us. About 20 dollars, or seven bucks a head. The price was higher than the standard tourist bus excursion, but this way, we had private transport and could potentially control the time of our return. To be sure that this guy was legit, I asked for his registration as a tourguide licensed by Uttar Pradesh Tourism. He gave it to me. He offered us a private car and driver, with us calling the shots of how much time we wanted to spend at each place. I was prepared to agree to it, but first I made it very clear that we would pay 550 rupees total, for all three of us, and not 550 rupees per person. "No problem, no problem," he said. I repeated my concern, and said that if he asked us for anything more than 550 rupees, we would walk away at the end of the day and pay nothing. "550 rupees, promise," he said, and grabbed my hand to shake it. The man behind the inquiry desk handed him a signout sheet and asked me to initial it. Susanne, Philip and I huddled for a moment and decided to go for it, but we made it clear with the man one last time that there would be no funny business. "No problem," he repeated again, this time with a wide smile on his face.

We exited the train station and climbed into his driver's white Ambassador as we began the short drive to Shah Jehan's masterpiece, the Taj Mahal. After about five minutes, the driver pulled over and our guide, who had finally introduced himself as Bobby, said we would now change cars. Another Ambassador pulled alongside. I looked at our gas gauge and saw we were almost out of fuel, so it appeared we were filling up by changing to a new car. It felt more like a getaway strategy, but we elected to not be overly concerned.

Ten minutes later, we pulled up to the outer gate of the Taj. Bobby, a keen talker whose commanded a strong English vocabulary despite his thick accent, spent a few minutes going over the history of the Taj. He said the Mughals were Persians from Tehran. Whatever happened to them being Mongol/Turkic descendants of Ghengis Khan from Central Asia? Well, I didn't feel like starting an argument. Bobby then surprised us with a warning: "The Taj has many bad people who will rip you off. Hide your valuables under your clothes, hold your camera tight, and don't let anyone touch you." Comments such as these from Bobby were making us feel a lot more comfortable with him, and as the day would progress, we'd recognize that if anything else, he was always sincere and upfront about everything.

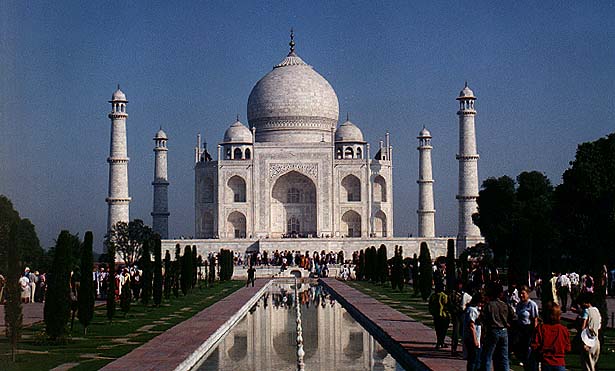

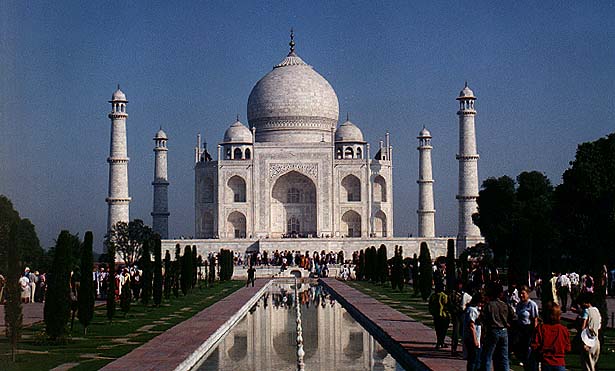

We purchased our tickets and headed down a stone path that opened into a garden. Ahead and to our right we could see a large red gate, beyond which lie the Taj Mahal itself. We joined the queue to pass through the gate, where we had our bags searched and had to walk through a metal detector (which seemed somewhat pointless, since each and every one of us set the thing off with our metal-laden cameras in hand). And then there it was, the Taj Mahal. Its status as a national symbol ranks as an equal to the Eiffel Tower, the Statue of Liberty, or even the Pyramids of Egypt, but unlike those structures I never actually figured I'd have the opportunity to visit them in the foreseeable future. It was in marvelous condition, even by western standards - too many of India's great monuments have withered because of neglect. It may be almost 350 years old, but the Taj still carries the luster of a modern structure.

The closer we got to the stairwell up to the Taj's main platform, the more dense the company around us became. There were hundreds of people jammed up front - mostly Westerners in large tour groups, with the occasional large Indian tourist family. I felt like I was at Disney world or back home in Washington lining up to see the Hope Diamond at the Smithsonian. I didn't like it.

We left our shoes outside as we ascended the stairs to the main platform and entered the Taj's tomb chamber. Unfortunately, the basement entrance to the cenotaph of Shah Jehan and his wife, Arjumand Banu Begam (better known as Mumtaz Mahal, "Elect of the Palace"), were closed for renovation, so people prostrated themselves on the floor to get the best angle down the basement steps into the cenotaph. If I didn't no better, it would have looked like people were paying devout respect to the dead emperor. With the real cenotaph closed, we had to satisfy ourselves with the false tombs that sat directly above the cenotaph basement. Hordes of visitors paced the bogus mausoleum clockwise, pressed together as if we were visiting the Mona Lisa. The false tomb was surrounded by a thin, almost translucent wall of intricately cut pietra dura inlaid marble, sparkling with thousands of gems. The costs Shah Jehan spent to build this tribute to his favorite wife must have been enormous (he was probably driven by guilt over her death, for she died in trasit while pregnant with their 14th child, having been dragged by Shah Jehan on one of his many Deccan campaigns in the south). No wonder legend has it that his son Aurangzeb overthrew him when he suggested he'd build a second Mahal (a black one, no less) for himself and his next favorite wife. Wasteful spending gets you every time.

The three of us exited the Taj and walked around its platform, getting a marvelous view of the mosque of Shah Jehan, a stunning red sandstone building just to the left of the Taj, as well as the Jamuna river, which passed behind it, and the hazy, blurred image of the Agra fort, several kilometers upriver. After having our fill of wandering the Taj and its grounds, we headed back to meet up with Bobby. I picked up a few postcards, including a picture of Mother Theresa and a shot of the erotic art at Khajuraho, to the southeast in neighboring Madhya Pradesh.

The three of us exited the Taj and walked around its platform, getting a marvelous view of the mosque of Shah Jehan, a stunning red sandstone building just to the left of the Taj, as well as the Jamuna river, which passed behind it, and the hazy, blurred image of the Agra fort, several kilometers upriver. After having our fill of wandering the Taj and its grounds, we headed back to meet up with Bobby. I picked up a few postcards, including a picture of Mother Theresa and a shot of the erotic art at Khajuraho, to the southeast in neighboring Madhya Pradesh.

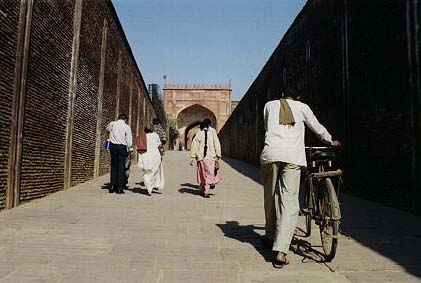

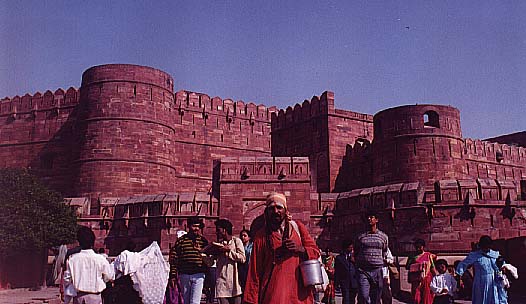

We then made the short drive up to the Agra Fort, the older brother of Delhi's Red Fort. The Agra Fort's construction was begun by the emperor Akbar in 1565, but additions were made through the time of Shah Jehan 100 years later. It was in marvelous condition, with long courtyards that lead to numerous citadels and hidden chambers. After pausing for some Pepsis, we wandered past the massive Diwan-I-Am and across to the fort's main wall facing the Jamuna river. On the left corner of the rampart was the Mussaman Burj, or Octagonal Tower, a marble, open-air apartment built by Shah Jehan for his beloved wife, the aforementioned Mumtaz Mahal. Ironically, it was here that Shah Jehan died in 1666, having been imprisoned there by his ruthless son Aurangzeb eight years earlier. Aurangzeb is probably best known for his puritanical interpretation of Islam and his wild intolerance of Hindus, who he seemed to slaughter with relish at the drop of a hat.

We then made the short drive up to the Agra Fort, the older brother of Delhi's Red Fort. The Agra Fort's construction was begun by the emperor Akbar in 1565, but additions were made through the time of Shah Jehan 100 years later. It was in marvelous condition, with long courtyards that lead to numerous citadels and hidden chambers. After pausing for some Pepsis, we wandered past the massive Diwan-I-Am and across to the fort's main wall facing the Jamuna river. On the left corner of the rampart was the Mussaman Burj, or Octagonal Tower, a marble, open-air apartment built by Shah Jehan for his beloved wife, the aforementioned Mumtaz Mahal. Ironically, it was here that Shah Jehan died in 1666, having been imprisoned there by his ruthless son Aurangzeb eight years earlier. Aurangzeb is probably best known for his puritanical interpretation of Islam and his wild intolerance of Hindus, who he seemed to slaughter with relish at the drop of a hat.

In an attempt to torment his father, Aurangzeb held Shah Jehan under house arrest inside the Mussaman Burj during his father's final years, so the old emperor could view his masterwork Taj Mahal, but never visit it again. Even though Shah Jehan got the best view in the house, the wily Aurangzeb must have enjoyed knowing that Dad would never be allowed to set foot in the Taj again except for burial. He even sent his father a well-wrapped present with a message: "King Aurangzeb, your son," said the eunuch who brought in the package, "sends this plat to Your Majesty to let you see that he does not forget you." "Blessed be God," Shah Jehan responded, "that my son still remembers me." But inside the inlaid box the old king found the severed head of Dara Shukoh, his favorite son, who had been his heir apparent until the coup. Shah Jehan was so upset he went into convulsions and lost several teeth from a collision with a table. The gruesome prank was thought up by Roshanara Begun, a sister of the two brothers who had sided with Aurangzeb. (To quote Katherine Hepburn in her role as Eleanor of Aquitaine in The Lion in Winter, "What family doesn't have its problems?") Another daughter, Jahanara, responded by nursing him back to health and remained as his nurse until his death. Aurangzeb reigned for almost 50 years; by the time he died in 1707, the empire was in chaos and would not recover until the British co-opted it 150 years later. So even though the Mughals would reign in north India until the end of the Sepoy Mutiny in 1857-58, Aurangzeb was essentially the last Mughal emperor with any effective control of the country.

In an attempt to torment his father, Aurangzeb held Shah Jehan under house arrest inside the Mussaman Burj during his father's final years, so the old emperor could view his masterwork Taj Mahal, but never visit it again. Even though Shah Jehan got the best view in the house, the wily Aurangzeb must have enjoyed knowing that Dad would never be allowed to set foot in the Taj again except for burial. He even sent his father a well-wrapped present with a message: "King Aurangzeb, your son," said the eunuch who brought in the package, "sends this plat to Your Majesty to let you see that he does not forget you." "Blessed be God," Shah Jehan responded, "that my son still remembers me." But inside the inlaid box the old king found the severed head of Dara Shukoh, his favorite son, who had been his heir apparent until the coup. Shah Jehan was so upset he went into convulsions and lost several teeth from a collision with a table. The gruesome prank was thought up by Roshanara Begun, a sister of the two brothers who had sided with Aurangzeb. (To quote Katherine Hepburn in her role as Eleanor of Aquitaine in The Lion in Winter, "What family doesn't have its problems?") Another daughter, Jahanara, responded by nursing him back to health and remained as his nurse until his death. Aurangzeb reigned for almost 50 years; by the time he died in 1707, the empire was in chaos and would not recover until the British co-opted it 150 years later. So even though the Mughals would reign in north India until the end of the Sepoy Mutiny in 1857-58, Aurangzeb was essentially the last Mughal emperor with any effective control of the country.

To the right of the tower was another complex, Jehangir's Palace, the Jehangiri Mahal. Akbar built the palace for his son, crown prince Jehangir, who eventually reigned for a generation following Akbar's death in 1605. Jehangir was later followed by his own son, Shah Jehan, in 1628. Unlike much of the rest of the fort, which typifies Mughal architecture and its Central Asian roots, Jehangir's Palace was influenced by elements of Hindu and Jain art, with the incorporation of elaborately carved buttresses and domed chattris. Adjacent to the Palace was a large courtyard which contained an odd octagonal pit. We couldn't figure out what it was for, but I joked it was His Majesty's Mughal Hibachi.

To the right of the tower was another complex, Jehangir's Palace, the Jehangiri Mahal. Akbar built the palace for his son, crown prince Jehangir, who eventually reigned for a generation following Akbar's death in 1605. Jehangir was later followed by his own son, Shah Jehan, in 1628. Unlike much of the rest of the fort, which typifies Mughal architecture and its Central Asian roots, Jehangir's Palace was influenced by elements of Hindu and Jain art, with the incorporation of elaborately carved buttresses and domed chattris. Adjacent to the Palace was a large courtyard which contained an odd octagonal pit. We couldn't figure out what it was for, but I joked it was His Majesty's Mughal Hibachi.

We wrapped up our trip to the fort and rejoined Bobby and our driver, whose name I never managed to get. Once again, our car had been switched and the original Ambassador from which we first departed had magically rematerialized. Bobby suggested we head to Fatehpur Sikri, an hour's drive to the west. We dissented and requested a lunch break. I wanted to choose something from the LP guide, but Bobby insisted on making his own recommendations. I assumed he'd be getting a commission for it. As it turned out, the first two restaurants he suggested were my first two picks out of LP anyway, but neither of them had opened yet. Bobby then suggested a third restaurant that wasn't listed, but we decided to go with his idea and give him the benefit of the doubt.

Bobby made a pretty good choice. The restaurant had a lovely grass lawn set up with tables, chairs and parasols. It wreaked of English high tea, but we thought that might be kind of cool and worth a try. As we sat outside, a family of Rajput musicians, including an adorable four-year-old in a big red turban, played Central Asian and Rajasthani folk songs. The food was quite good - we ordered afghan chicken (ground chicken with spices on skewers, grilled in a tandoor oven), a mutton curry and potato curry, as well as a selection of regular and stuffed naans. We feasted for an hour in the shade, and as we departed, Susanne got a few shots of the boy in the turban, who seemed delighted by the five rupee reward he received for posing.

We climbed back into our Ambassador and started the long drive west to Fatehpur Sikri, Akbar's mythical abandoned palace city. To get there, we first had to wind our way through the congested, colorful streets of Old Agra. It was an incredible experience, hard to put down in words. Thousands of people in markets and stalls, wearing the brightest colored saris and dhotis imaginable. Scattered pockets of Muslim women, wrapped in black or blue chadors. Little girls draped in yellow, pink, green silk. It was almost like we had been transported back to the time of Aladdin - Agra must have been an amazing crossroads between the heart of Deccan India, Central Asia, and even Afghanistan and Persia. We were also overwhelmed by Diwali candy stalls covered by swarms of flies, brahma bulls lounging around as if they owned the place, motorcycles carrying a full family of five, dogs, hogs, and the occasional monkey wandering the streets for scraps. We tried to get as much of it on film, but no photograph could ever capture the life and color that radiated from the streets of Agra that sunny afternoon.

The traffic began to thin out and we soon found ourselves along a rural path heading due west to Fatehpur Sikri. Fields of anise and other spices were almost ready for harvest. And with each passing vehicle, it always felt like a near miss - we would pass on the right of a donkey cart with ten kids packed in back as a truck barreled towards us, with have the road washed out by monsoons, and cows napping on what was left of the pavement - and yet we would hurl past each obstacle with only inches to spare. No wonder Indian vehicles don't have rear-view mirrors on the sides of the windows, or they'd be knocked off on their first drive through an intersection. Barely a minute went by without us holding our breaths as we avoided another near miss. At one point, Philip said to Bobby, "Tell him he drives very well." The driver, an older and darker man who had yet to speak the entire trip, smiled and said "Thank you. I understand few English." They were the only words he ever uttered.

After an hour of driving, we reached the outer walls of Fatehpur Sikri. I wondered what the circumference of the walls were - they extended as far as the eye could see. We then drove up a hill for half a mile or so to reach the main palace entrance. Akbar had built the palace in the 1570s as a happy response to the successful fertility of one of his wives. For years, they had tried to produce a male heir, so when they finally did, Akbar decided that a new palace was in order. Incredibly, Akbar and his court occupied Fatehpur Sikri for only 14 years, abandoning it for a new capital much further north in Lahore, now in Pakistan. Local storytellers will repeat the tale that Akbar was forced to leave because Fatehpur Sikri had no sustainable source of water. Modern historians now dispute this explanation as apocryphal, though; instead, it is now believed that military pressures from kingdoms to the north forced him to move to Lahore, a strategically located city that would afford Akbar a better perspective of his border situation.

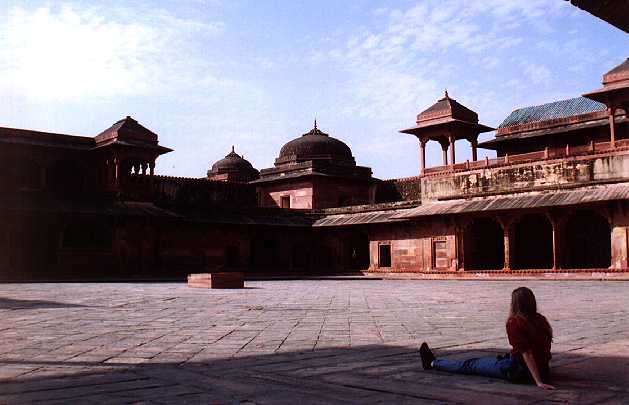

From the gate, we could see a high red sandstone wall that blocked our view of what was beyond it. To the left was the Sikri Mosque - equally enormous, equally red. We headed into the main gate and around the corner of the wall to the main palace area. I know I keep using the word 'red' a lot in my descriptions of India and its stone monuments, but 'red' can't even begin to describe the absolute ruddiness of everything here - the masonry, the towers, the pavement, all a beautiful, dark, almost ochre red, truly unlike any other red I've ever seen.

We lost Philip for a while as he wandered off on his own. Susanne and I climbed to the fifth floor of the Panch Mahal, the highest pavilion on the plaza. Akbar apparently used to sit at the top of it to watch performances from it or to play hide and seek with his harem, who would hide within its seven stories. Akbar was also partial to playing games of pachisi or even chess in the adjacent square, using his eunuchs and harems as human chess pieces. He'd even use some of the enclosed courtyards as hunting grounds - wild and exotic beasts would be released, while he perched himself atop a pagoda or other tower with flintlock in hand. Ah, it's good to be the king.

Climbing down from the Panch Mahal, Philip reappeared, so we continued to inspect the grounds, trying to take in all of its splendour. Here was a palace city, built by perhaps the greatest of the Mughal emperors. Parts of it even had an uncanny similarity to the Forbidden City in Beijing, but on a smaller and more compartmentalized scale. Eventually, though, we started to work our way out of the palace. There was a small passageway we had neglected to visit earlier, so Susanne and popped her head in to see what we would find. A few seconds later I could hear her say, "Andy, you want to take a look at this." Inside, the gate opened up to a beautiful courtyard, about 100 feet square, with marvelous tiers of balconies on all sides. I looked to Susanne and said, "The Last Emperor," in reference to the Academy Award-winning Bertolucci film on the fall of China's final imperial dynasty. She simply said, "Uh huh," as she gazed around in wonder. We had discovered Jodh Bai's Palace, the principal residence of Akbar's harem. It was truly incredible what could be hidden around any corner at Fatehpur Sikri, let alone India itself. We would have to be mindful of avoiding other near-misses.

Climbing down from the Panch Mahal, Philip reappeared, so we continued to inspect the grounds, trying to take in all of its splendour. Here was a palace city, built by perhaps the greatest of the Mughal emperors. Parts of it even had an uncanny similarity to the Forbidden City in Beijing, but on a smaller and more compartmentalized scale. Eventually, though, we started to work our way out of the palace. There was a small passageway we had neglected to visit earlier, so Susanne and popped her head in to see what we would find. A few seconds later I could hear her say, "Andy, you want to take a look at this." Inside, the gate opened up to a beautiful courtyard, about 100 feet square, with marvelous tiers of balconies on all sides. I looked to Susanne and said, "The Last Emperor," in reference to the Academy Award-winning Bertolucci film on the fall of China's final imperial dynasty. She simply said, "Uh huh," as she gazed around in wonder. We had discovered Jodh Bai's Palace, the principal residence of Akbar's harem. It was truly incredible what could be hidden around any corner at Fatehpur Sikri, let alone India itself. We would have to be mindful of avoiding other near-misses.

The mosque on the other side of the gate was getting crowded with people for mid afternoon prayers, and the descent of the sun had created a prohibitive glare for our cameras to get any acceptable pictures of it. So after a quick look of the building's entrance, we found Bobby and our driver and headed off. The ride back was quite, for we were all very tired by this point. It was 4pm by the time we reached the train station to reclaim our bags. Bobby, however, insisted that we stop to see "the fine Mughal art" before departing to Mathura. Of course, we knew immediately that this was going to be a sales pitch of some kind or another. Surprisingly, though, Bobby was open about it and admitted that he would get a commission on anything we bought. We told him up front that there was no way we were going to buy anything, but if he wanted to make a quick stop - no more than 30 minutes or so, that would be find. Just as long as we were on the road to Mathura by 5pm, we were game.

The workshop and store he took us to was called the Cottage Industry Emporium, Ltd. Very Indian, I thought. We were led to a room where eight boys, probably around 14 or 15 years old, were making pietra dura inlaid marble platters. Admittedly, the workmanship and the delicate patterns of the inlaid semiprecious stones was impressive, but I kept on seeing child labor laws flashing before my eyes. I asked them how long a single piece, about 15 inches in diameter, would take to finish. "One month," the emporium manager said. I assumed these kids weren't allowed a 9-to-5 lifestyle, so I can only imagine how many hours were put into each platter.

After being taken through a series of rooms full of stones, silks, saris, silver, jewelry, pottery, carvings, carpets, and perfumes, we politely thanked them but declined any purchases, citing the enormous price tags of hundreds and even thousands of dollars per item. We then headed back to Bobby's home base, where all the drivers hung out while waiting for their next assignment. We parted company with Philip and exchanged email addresses so we could get copies of each other's pictures. After taking a picture, we said goodbye to Bobby and our anonymous, quiet driver, as were to now take a minibus to Mathura while they headed home for the night. We paid RS 550, just as he had original quoted, but we threw in another 200 rupees for good measure. All in all, at about eight bucks a person, it wasn't a bad way to spend the day.

After being taken through a series of rooms full of stones, silks, saris, silver, jewelry, pottery, carvings, carpets, and perfumes, we politely thanked them but declined any purchases, citing the enormous price tags of hundreds and even thousands of dollars per item. We then headed back to Bobby's home base, where all the drivers hung out while waiting for their next assignment. We parted company with Philip and exchanged email addresses so we could get copies of each other's pictures. After taking a picture, we said goodbye to Bobby and our anonymous, quiet driver, as were to now take a minibus to Mathura while they headed home for the night. We paid RS 550, just as he had original quoted, but we threw in another 200 rupees for good measure. All in all, at about eight bucks a person, it wasn't a bad way to spend the day.

Susanne and I hopped into the minibus with our new driver and hit the road. The first hour of the 90-minute trip to Mathura was pretty dull, apart from a brief stop at a train crossing which allowed us to get out for few minutes and watch men on bicycles play chicken with the oncoming locomotive. But once the sun set around 6pm, the real adventure kicked into high gear. While driving Indian-style in the daytime was fun and exciting, at night it was terrifying. Indian drivers, apparently, aren't big fans of using their lights at night, except to flash other cars while passing them for driving too slowly. I felt like I was playing the old Atari 2600 game Night Driver, but instead of hurling down a pitch black, semi-deserted highway, we were hurling down a pitch black, traffic-laden, occasionally paved road that included horse-drawn carts, autorickshaws, bicycles, pedestrians, dogs, hogs, and cows. To top it all off, once we reached what appeared to be Mathura, our driver got lost. He had no idea where the train station was. If it had been any closer to our train's scheduled departure time, I think I might have lost my cool. But since we had three hours to kill there, I relaxed and hoped for the best. Within 20 minutes or so, the driven had gotten enough assistance from the locals that we made it to the train station with plenty of time to spare.

Mathura Railway Station is a swarm of people, luggage and animals coming and going all over India. It was refreshing compared to the Agra and New Delhi stations, for Mathura attracted few westerners apart from the occasional Hare Krishna pilgrim, so there were no touts whatsoever to harass us. The ticket windows had hundreds of people, if not as many as a thousand of them, jammed inside the covered courtyard that made up the entryway into the station. Though the locals stood their ground when it came to queuing for tickets, the lines were occasionally broken up by a chai-wallah offering hot tea or a wandering cow that had made its way into the station.

The train information board was all in Hindi, and the man behind the inquiry desk couldn't speak a word of English, so I made a feeble attempt to find our train number listed on the board, just to see if I could spot a time listed with it. I couldn't find it. I was getting a little concern at this point, so we wandered around until we found someone we hoped would speak English. We eventually did - a large man in a Nehru jacket, Congress hat and thick black glasses. He wore a large gold class ring on his right hand. He kindly helped us and explained that our train would come in on schedule just before 9pm on platform one, just out the next door.

As we walked the platform in search of a place to relax, I was struck by the clothes of the people waiting for the trains. I guess they were dressed just like everyone else in Uttar Pradesh, but now that I had a few hours to sit back and people-watch, the character and style of the local dress began to make sense before my eyes. So many people in heavy shawls and scarves wrapped around their heads. If you had shown me a snapshot of this scene, I would have labeled it as a train station in Kabul or Isfahan. The continuing Persian and Central Asian influence on northern India was everywhere, it seemed. I could hardly wait to see what the south of India would be like, since the Aryans, Persians and Mughals never conquered those cultures.

As we walked the platform in search of a place to relax, I was struck by the clothes of the people waiting for the trains. I guess they were dressed just like everyone else in Uttar Pradesh, but now that I had a few hours to sit back and people-watch, the character and style of the local dress began to make sense before my eyes. So many people in heavy shawls and scarves wrapped around their heads. If you had shown me a snapshot of this scene, I would have labeled it as a train station in Kabul or Isfahan. The continuing Persian and Central Asian influence on northern India was everywhere, it seemed. I could hardly wait to see what the south of India would be like, since the Aryans, Persians and Mughals never conquered those cultures.

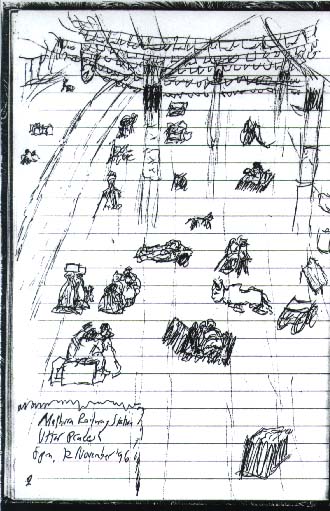

We sat in the First Class waiting room where we talked to a nice family from Bhopal. Their little girl, who looked around 11, spoke very good English for her age. We talked about where we were going, where she had traveled in India, and what her favorite places were (Gujerat, in western India - interesting choice). After they left for Bhopal, I went outside on the train platform, plopped myself down, and made a feeble attempt to capture the scene in a drawing. My rough image of the platform was pretty good, but I lack the artistic talent or the motor skills to draw details of all the animals and people that were there. So not wanting to ruin the drawing with lots of stick figures, my platform picture is much less crowded than the original scene that night.

At 8:30pm, 30 minutes before the train's schedule departure, an old man who was also going to Varanasi said that the train was running an hour late. No biggy, I thought. At just before 10pm, we headed out with our backpacks to platform one. We waited for a while, but there was no sign of the train. Meanwhile, a crowd had gathered next to us. Clearly we had become the main attraction at Mathura Railway Station that night, being the only westerners there. Soon we were approached by a well dressed young man, about 20ish. Being the suspicious person that I am, at first I was cautious about the questions he asked us. Soon enough, though, it became quite apparent that he was just a typical Indian college kid interested in America and wanting to practice his English.

We talked to him and his friend for about an hour (yes, the train was getting later and later). They were both juniors at Benares Hindu University in Varanasi, studying engineering. We talked about the US elections, world politics, Chicago, and other things, though Susanne and I did most of the yakking. They commented on our big backpacks and how uncomfortable they looked - "Why do you Americans and Australians wear them? They must be bad for your back," one of them said. I insisted he try mine on. "Not bad," he said, after walking in circles with my 25 pounds of clothes and junk on his back.

Finally, our train arrived soon after 11pm. Our university friends first took us to the end of the train, where they had thought our reserved berths were. It turned out we were all the way on the other end, and fearing that the train was about to leave, we made a mad dash for it. We hurdled along, steering around crowds, cows, and luggage, but just before we reached our car, I accidentally collided with a large metal dolly that was being used for loading the luggage on board. I smashed both of my shins into it and nearly did a forward flip over the thing, but I somehow managed to keep both feet planted on the ground (good thing my backpack provided ample ballast to keep me down). As my legs throbbed with pain, we jumped onto the train as it began to roll away from the platform. That was a first for me.

We found the assistant conductor, who started to review our tickets. "One person only," he then said, to our complete shock. I showed him the part of our ticket that said "Persons: 2," to which he responded by pointing to his manifest. Indeed, my name was listed, but not hers. Meanwhile, I began to notice a warm trickle down each leg - apparently the collision with that dolly had done more damage than I had thought initially. Thank god I was wearing jeans or I might had split my skin through to the bone.

Meanwhile, I began to argue persistently with the conductor. "Look, I paid for my two sleepers. What do you want to do, throw one of us off while the other goes solo to Varanasi?" He then started to scribble something down in Hinglish. "40 rupees," he then said to me with a straight face. I knew there were space on the train, but this guy was going to insist on a kickback just to keep our asses from getting tossed of the train at the next stop. "40 rupees, problem solved," he repeated. I then realized that 40 rupees was the equivalent of about $1.10, so if it was going to take a measly $1.10 bribe to avoid unnecessary misery, so be it. 40 rupees.

After our conductor extortionist completed his paperwork, he led us to our sleepers. Unfortunately, we didn't have our own compartment as we had assumed. Instead, we were in a pair of two-tiered bunks that lined the passageway down the train car. Only a curtain separated us from passengers as they walked back and forth down the car. We were given sheets and pillows, but the bunk itself was a little too firm for comfort. It was like camping on a sheet of tight rubber. I was reminded of the Star Trek: Next Generation episode where Data and Picard were getting a ride on a Klingon destroyer. Their compartment was bare, apart from a slab of steel protruding from the wall, which served as their bunk. "This is not a pleasure craft, Picard," the Klingon captain hissed. "This is not a pleasure craft, Sahib," I could hear that damn conductor say to me in my head. I made my bed, washed off my wounds with some handy-wipes and neosporin, and settled in for the night.

Yet despite the hustle and bustle from other passengers skimming by my bunk, I slept rather well. At first, the sleeper was unbearably hot, then cold, then hot again. I became adept at removing and replacing my shirt and sheets as necessary, depending on the current conditions. Then, at some god-awful hour of the night, I awoke to find Susanne plopped on top of my legs. It took me a second to regain consciousness and recognize her, so my first instinct was to give her a good swift kick to get her away from my backpack. Fortunately, I restrained myself for a second to figure out who she was. Once I got my bearings, I asked her what she was doing there. "I am sooo sick," she moaned, apparently after having spent the better part of the evening running back and forth to the Indian-style squat toilet. There wasn't much I could do besides give her some water, and a few Peptos, but I then remembered I had packed some Imodium AD for emergencies. She took one and climbed back into bed. I fell back asleep quickly.

Take me back to the journal index.

Take me back to Andy's Waste of Bandwidth.