|

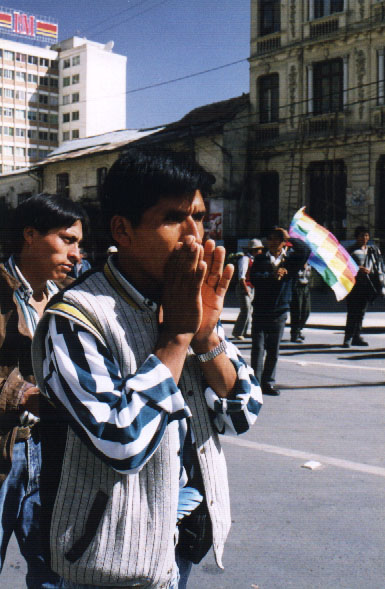

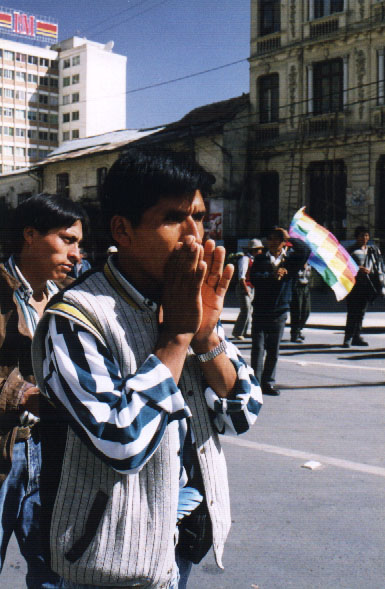

Another day of cocalero

protests along the Prado |

Once more I was up after sunrise: 6:30am to be exact. Assuming our Tiwanaku tour wasn't scrubbed yet again, we planned to board a bus outside the hotel at 8 o'clock in order to catch our connection to the ruins. This gave me plenty of time to get dressed, have some breakfast and walk around the neighborhood in search of a bakery. I wasn't sure if when we'd have access to food at the ruins, so I figured we should stock up on some supplies before getting on the bus. Around the corner from the hotel I found a shop that sold fresh bread, so I bought six large rolls for a grand total of one boliviano. Susanne, meanwhile, waited in the reception room watching some terrible early morning TV soap opera. A large Vicuña Tours bus pulled up in front of the hotel just after 8am. Finally - we were going to Tiwanaku.

The bus drove several blocks to Sagárnaga and headed up hill, towards the Huari restaurant where we'd had lunch the day before. The bus stopped next to the Diana Tours agency, where we waited with a British couple for the arrival of our Tiwanaku bus. Apparently the couple was in the midst of a two-year trip around the world, having worked their way across Europe and Asia to South America. Oddly enough, they were using Los Angeles as their base and were now hop scotching all over the New World before catching their final flight to London. As it turned out Susanne and I had traveled to many of the same places as they had, including India and Laos. Though we were all in agreement in our strong positive feelings toward Laos, we were divided on our opinions of India. Susanne commented how much she had enjoyed Varanasi, but the British man's response surprised us.

"You know," he said, "the first time I visited Varanasi I was impressed. But after having spent several months wandering the country, learning more about it, I came to the sad conclusion it was all a sham. There's nothing sincerely mystical about that place. It's all just image and money."

"I hope we'll go back to India soon," Susanne replied, "but I hope we don't end up with the same conclusion."

"For your sake, I hope so too," he answered, shrugging his shoulders.

As we talked about our travels, I nearly lost sight of the fact that we had been sitting there for 45 minutes and were still waiting for our bus to arrive. A short man then appeared in the doorway, his hat held in his hand as if he were the bearer of bad tidings.

"I am very sorry," he said, "but the tour has been canceled. Cocaleros are blocking the main road again."

I couldn't believe it - four days in a row we were out of luck. "Will we be able to get a refund?" I asked.

"No problem," he replied, "just go back to your hotel or the Vicuña Tours agency."

Not sure what to do next, I suggested we stop at the Snack el Montañes café across the street and figure out how we'd spend the day. Snack el Montañes was a small restaurant with weak coffee and bad music, but it gave us time to think. On the wall I noticed a sign for a local tour agency that was promoting "Treks, jungle tours and Jeep raids." Jeep raids? They must mean Jeep rides. "I can picture it now," I said to Susanne. "For only 200 bolivianos you too can pillage a local Altiplano village."

My mood began to sink as I thought about the Tiwanaku tour that wasn't to be. "You know," I lamented, "I came to Bolivia with two major goals: Spend a night on Isla del Sol in Lake Titicaca, and visit the great ruins of Tiwanaku." I felt like there was a score board on the café wall - Bolivia: 2, Andy: 0.

"But look at it this way," Susanne replied, putting a positive spin on things. "At least we really enjoyed La Paz, which was certainly unexpected. Next to Machu Picchu it's been my highlight of the trip. And we still have one more day here to relax here."

This proved to be some consolation. "I guess we'll just have to come back to Bolivia," I said. "I always figured this would be one of those countries where you'd go once and never come back, but now we've got a few good reasons to try again. Besides, we've barely even scratched the surface here; we've still got Santa Cruz, Sucre, Rurrenabaque and a bunch of other interesting places to visit."

Giving up on Montañes' coffee we returned to Plaza San Francisco and stopped at the headquarters of Vicuña Tours, hoping to get our money back. "I'm sorry," a woman told us, "but you can't get your money back here. Try the agent at your hotel." Her suggestion certainly made sense, but I had a bad feeling we were about to get screwed. Instead of worrying about it, though, we wandered the shops around the Iglesia San Francisco in search of some alpaca wool slippers for Susanne. We soon found a small shop run by an old woman, who fitted Susanne with a beautiful pair of furry, warm slippers for only 25 bolivianos. I was a little jealous - they look so much more comfortable than the ones I bought two weeks earlier in Cusco.

|

| Cocalero protester |

As we stood in front of the Iglesia, looking out over the plaza, I could hear martial parade music coming from large speakers across the street. It seemed a little out of place - nothing appeared to be going on that morning, and no one else was paying attention to the music. A few minutes later, though, another column of cocalero demonstrators came marching up the Prado. There weren't as many people marching as there had been yesterday, but they seemed just as determined, waving signs and shouting out slogans. I then realized why there was music playing along the street: the authorities were trying to drown out the voices of the protesters. The music seemed to get louder as the demonstrators marched onward. Whatever they were here to say, few people paid attention to it. Once again I slipped into the march - this time joined by Susanne - and snapped some photos of the protesters. I didn't feel the same rush of excitement as I had the day before, yet I still felt something - an inner drive to be in the middle of it, to capture it, to bear witness. Even if all of La Paz didn't want to hear what these cocaleros had to say, I still wanted to be a part of it.

After the march made its way up the Prado, we stopped briefly to cash a traveler's cheque before returning to the hotel. As we entered the hotel reception area, the tour agent saw me and shook her head in surprise.

"I am so sorry your trip was canceled again," she said.

"We're leaving for the US tomorrow morning, so it looks like we'll have to get our money back," I replied, trying not to sound too frustrated.

"Of course," she answered, "would you like bolivianos or dollars?"

I was immediately relieved by her response. Perhaps I've become too jaded by bad travel experiences, but I honestly expected some kind of run-around from her. After she returned my money I felt guilty for being so suspicious.

Katrina was also working that morning, so I told her we'd like to see a peña that night, assuming there was one that started fairly early. "We are leaving tomorrow before dawn," I explained, "so we can't be out too late."

that night, assuming there was one that started fairly early. "We are leaving tomorrow before dawn," I explained, "so we can't be out too late."

"How about Huari Peña," she replied. "It should start no later than 9pm."

"Huari Peña would be great," I answered. "We were there for lunch yesterday and really enjoyed it."

After making a quick phone call, Katrina turned to us and said, "OK, you're set for Huari Peña. Be there by 8pm so you can eat dinner before the show starts. Have fun..."

Meanwhile, it wasn't even 11am yet, so we needed to figure out what we would do with ourselves for the rest of the day. I suggested we take a walk down the Prado towards the Sopacachi neighborhood and perhaps get lunch at Café Montmartre. I was eager to find a copy of the International Herald Tribune to see if there was any news regarding President Clinton and the Monica Lewinsky scandal - the Starr Report could come out any day if it hadn't already. If any part of La Paz would have a decent international bookstore, the Prado would.

|

| The Prado, La Paz |

Or so I thought. Susanne and I walked down the northern side of the Prado, ducking our heads into magazine stalls and bookshops. To my surprise I couldn't find any periodicals in English. Some of the stalls had copies of Newsweek's special scandal edition which I read earlier on the train from Machu Picchu; otherwise all the papers were in Spanish. That was okay, though; it provided us with a fine excuse to stroll down this cosmopolitan boulevard. Perhaps I'd even find a place to buy some Cuban cigars, assuming they sold them in Bolivia, I thought to myself as we passed the university. If not, we still had a decent lunch ahead of us.

We walked another 20 minutes or so until we reached Sopacachi. Café Montmartre was still closed - it didn't open until noon - so we decided to walk uphill beyond the café, just to look around the neighborhood. Sopacachi truly was Bolivia's answer to Georgetown - colonial brownstones and luxury homes connected by a rolling hill of cobblestone. We reached an indoor market which we briefly explored - I was drawn inward by the smells of orange bushels and smoked sausage that hung over the stalls. The fresh scents made me hungry, not to mention glad that noon had struck; Café Montmartre was open for business.

We returned to the restaurant and settled at a small table with thick slices of bread set out in a basket. As soon as we sat down a waiter approached us and asked us what we wanted. "Uno momento, por favor," I asked, though he responded by shaking his head in frustration and walking away. "What's up with him?" I grumbled. "He hadn't even given us a chance to open our menu."

Susanne and I each found a crepe on the menu that sounded good, but it took us another 15 minutes to get our waiter back, despite the fact we were the only people in the restaurant. Eventually he took our order and spent the next half hour standing behind the bar, singing along with the most awful easy-listening R&B playing on the radio. Our crepes arrived, completely cold, which worried us simply for sanitary reasons. I didn't relish dealing with our waiter any more than we had to, but by this point I was getting really annoyed. Not knowing how to complain about it in Spanish, I said in French that the crepe was tres froid, to which the waiter responded by pressing his index finger into it. That certainly didn't make me any happier, but at least it got him to realize that the crepes were truly tepid. After taking away our plates for a few minutes our crepes reappeared, steaming hot and ready for eating, which we did as promptly as possible just to get out of there.

As we strolled back down the Prado towards the hotel, Susanne and I were able to walk without our jackets on for the first time since the Sacred Valley near Cusco. The temperature had crept up into the mid 60s and it was beautiful outside, so we returned briefly to the hotel to drop off our jackets before heading out for another long walk. We soon passed Plaza Murillo and continued down Calle Commercio, which appeared to have even more soldiers than we'd seen the day before. "I wonder what's up today?" I asked Susanne.

"I don't know," she replied, looking around the street. Susanne pointed to a small group of soldiers leaning against a barricade. "That would be such a great picture," she sighed.

"Then ask them if you can take it," I said matter-of-factly. "The worse they'll probably do is say no, right? I mean, it's better than taking your shot covertly and getting caught."

Susanne agonized over her decision for a few moments before taking a deep breath and approaching the soldiers. I kept out of the way, leaning against a wall on the other side of the street. Susanne soon returned and shook her head. "They said no," she said, "but they were very nice about it."

|

| Campesinas chatting near the Witches' Market, La Paz |

Since this was our last afternoon in La Paz, I suggested we walk up to the Witches' Market for some last-minute shopping. I still needed to buy another Pachamama statue for my mom; besides, there had to be some little trinket Susanne might want to buy for herself. I also wanted to look for a large alpaca wool blanket, which meant I'd have to buy some kind of tote bag to bring it home on the plane. As soon as we arrived at the first market stall I found a small statue that seemed just right. Meanwhile, Susanne looked over at several small clay animals, including a little turtle that was painted dark green. We quickly bought the two items and used the occasion to get a couple extra snapshots of the market. I then poked around several shops for a tote bag. Most of the shops had similar rectangular bags for around 30 to 40 bolivianos, so it was really a matter of finding one that was the right size and color. Just past Calle Sagárnaga I found one shop that was selling green totes for 40 bolivianos, which I soon bargained down to 30 bolivianos. Now all I needed was a blanket to put in it.

There were several large stores along Calle Comercio, so I suggested we return to the pedestrian mall and see if we could find one that sold blankets. As soon as we walked uphill to the street, I saw a store with large faux tigerskin blankets and Persian rugs hanging in the window. Inside we found a warehouse filled with enormous piles of blankets and rugs, every shape and size imaginable. An elegant woman in her sixties approached us and immediately spoke in English. "Good afternoon," she said. "Can I help you find anything today?" Before I could answer I thought to myself, "She must be Jewish." I know there are only several hundred Jews left in La Paz, but still it popped into my mind. It's just one of those cultural things, I guess - you can always spot a fellow member of the tribe.

Not wanting to break the ice with something as awkward as, "By any chance, ma'am, are you Jewish?" I explained I was interested in buying an alpaca wool blanket. The woman brought us over to a counter and pulled out three large blankets. "We have alpaca only in white, gray, and brown. We don't dye alpaca, so the colors are limited to the natural wool shades. They are $40 each for a queen size." Forty bucks was a bargain considering similar blankets could easily go for several hundred in the US, but I wanted some time to think about it.

"We'll be back in a bit," I told her.

"By all means," she replied as she escorted us to the door.

After debating the purchase over a round of cappuccinos at Café Torino, we returned to the textile store. The woman smiled as we entered, clearly knowing she had a sale coming. I told her I liked the feel of the alpaca, but I also liked the checkered patterns of some of the polar fleece blankets they had in stock. "Polar fleece is synthetic, you know," she said. "That's why they're only seven dollars." For seven dollars, I though, I could easily buy a polar fleece blanket on top of an alpaca blanket, so told her I'd take one of each. As she filled out a purchase form, a short old man went behind the counter and folded the blankets as tightly as possible in the hope of getting them to fit inside my green tote bag. Miraculously they took up every square centimeter inside the bag, bulging the tote to its seams. The woman then handed me the purchase form and asked me to take it to the cash register. As another older gentleman gave me change for my purchase, I noticed several diplomas hanging on the wall behind him: University of Michigan, College of Medicine. I couldn't exactly make out the calligraphy for the names, but one of them appeared to be Feinkalb. I guess that answered my earlier hunch.

With my densely packed green tote over my shoulder, we returned to Plaza Murillo and settled ourselves along an open bench. We still had four pieces of bread left over from our canceled Tiwanaku tour, so I suggested we use them to feed the birds. As we threw chunks of the stale bread to our horde of pigeons, Susanne said, "You know, I really liked those polar fleece blankets."

"We could always go back one more time," I replied. "Besides, they're beginning to feel like family."

"You're right," I replied, suddenly feeling very conspicuous. "For all they know we've got bombs in here. Let's just head back to the hotel." We continued our walk, ever aware of the attention we were garnering from the soldiers. Just as we reached the end of the pedestrian mall at Plaza Murillo, another group of several dozen soldiers marched briskly downhill, armed to the teeth with shields, shotguns and tear gas launchers. At the same moment we heard the sounds of shouts and small explosions - there was another cocalero march down along Avenida Potosi. The cocaleros were yelling out slogans and setting off cherry bombs. I couldn't understand why any protester in their right mind would blow up firecrackers in the presence of soldiers during an already tense situation. The fireworks were a double-dare in the extreme, an attempt to agitate the soldiers into reacting and causing an incident. This certainly wouldn't be the first time blood was shed on the avenidas of La Paz; in the past, leftist miners have even gone so far as to detonated dynamite sticks during their demonstrations. Bolivian protests were a daily game of block-by-block brinkmanship. It's amazing more people don't get killed doing these stunts.

As we heard the racket coming from the demonstrators, my first reaction was to run down the hill and see what was going on. Susanne wisely restrained me: "Andy, your bag." She was right, especially since I had already inadvertently drawn the attention of the soldiers with my green tote. The last thing I needed to do now was rush towards a police standoff with a densely packed bag bouncing over my shoulder.

"Let's get back to the hotel and drop these things off," I suggested. "It looks like the cocaleros are also walking east, so we might be able to catch up with them." We walked briskly towards the hotel, no longer an object of interest to the soldiers because most of them had charged down hill towards the marchers. Once we reached the hotel we quickly gathered our keys from the front desk and dropped the bags in our room. To our surprise, though, as we walked downhill towards Potosi we found nothing. No protesters, no riot police, only traffic. All the players had disappeared without a trace.

"Too bad we can't spend another day here," I said to Susanne, somewhat disappointed. "I'm sure the whole thing will just happen again. Let's just go back to the hotel and pack."

|

| Susanne poses in the Hostal Republica's courtyard |

Susanne and I spent about an hour organizing our luggage before departing for the peña at Restaurant Huari. The two blankets I bought provided an excellent place to stash the delicate pottery I had purchased, and because I'd gotten a separate bag for the blankets, I had plenty of room for the rest of my belongings in my backpack. One item I wasn't sure what to do with was the envelope of coca leaves given to me by the protesters at the rally yesterday. I thought it would be nice to have some coca leaves for my scrap book, but I couldn't imagine US customs officials looking too kindly on it. As I debated what to do with the leaves, Susanne interjected her thoughts on the subject.

"You're not actually going to bring those back, are you?"

"Okay," I replied, "I'll give them to some campesina tonight." I folded the envelope and placed it in my jacket pocket, not before securing several coca leaves between the pages of my Lonely Planet guide. If anyone asks, I told myself, I'll just say they were innocent bookmarks.

Just before 7:30pm we left the hotel and conducted our usual walk past Plaza Murillo and the Comercio pedestrian mall. There were a surprising number of people hanging out along Plaza San Francisco, perhaps because of the mild temperatures that night. Aymara men chatted away on benches under the lights of the great iglesia as campesinas sold bags of freshly roasted peanuts and small cups of green jello. By the time we walked up Calle Sagárnaga towards the restaurant I realized we had over 30 minutes until our dinner reservations, so we decided to stroll down Calle Linares and along the Witches' Market. The market itself was closed; everything in fact was closed by this hour. Linares was pitch black, and we guided ourselves down the cobblestones following the sounds of children playing further ahead. Susanne and I had the street to ourselves (or so it seemed, since we couldn't see the children several blocks away). We were both struck by an eerie sensation, walking through the echoing blackness of what even in the brightest of hours is literally a witches' market.

"This feels really strange being out here at night," I said to Susanne.

"I know," she replied. "Isn't it great?"

There was nothing to be afraid of - La Paz after dark is about as safe as any major capital can be - so we walked to the end of the market and back, saying goodbye to the street that had formed such a strong impression on us over the last several days.

|

| Girl playing along Calle Sagárnaga |

After returning to the corner of Linares and Sagárnaga we crossed the street and walked half a block, not far from the shop where I bought my tote bag. Unlike the Witches' Market, this particular block of Linares was still busy with people, though most of them were wrapping up their day's business. Susanne and I sat on the steps of an old building and peacefully watched the neighborhood close down for the night. Shop owners joked as they helped each other roll down their storefront shutters. Women opened second-floor windows and called for their families to come upstairs as the aromas of dinner drifted to the street below. A group of children, ever determined to keep playing until the last minute, held hands and danced in a circle like a Matisse cut-out come to life. Susanne and I said very little, choosing to enjoy the moment until we too had to come up for dinner.

We walked half a block uphill and reached the Huari just in time for our 8:30 reservation. The restaurant host, a man in his forties who looked like Carlos Santana with short hair, gave us a table in front of the stage and brought out two small glasses of pisco sour. I hadn't tasted one of these frothy Andean margaritas since the train ride from Cusco, so I sipped it with pleasure as I reviewed the menu. Susanne and I both wanted to enjoy a good meal tonight, but we also didn't want to have to cash any more traveler's cheques if we could avoid it. I noticed the entrees could come as half-orders, so I suggested we try out some of the soups and get smaller dinners. After both of us ordered llama jerky soup, Susanne selected a roasted half chicken while I further tempted the fates with a llama steak. Neither of us had any clue what we were getting into with the soup, but supposedly it was the specialty of the house.

The soup soon arrived, joined by a small bowl of roasted corn nuts. The sweet broth was laden with a generous portion of giant pasankalla corn kernels and semicircular slivers of what appeared to be sliced sausage. "I guess this is the llama jerky," I said to Susanne, trying to discern its taste. "Don't worry - it's just a light sausage."

"Feel free to finish mine," Susanne replied, not particularly impressed with it. I, on the other hand, enjoyed the soup, adding crunchy corn nuts to complement the large, chewy pasankalla kernels.

A waiter appeared with our entrees just after 9:20, about the same time the band showed up. I wondered when the peña would actually start, since it was scheduled for 9:30. My hopes for an on-time performance were shattered when the leader of the band, a stocky man who looked like Mandy Patinkin, sat down to a large plate of chicken for dinner. There wasn't much else for us to do except eat, which wasn't a particularly great experience. Susanne's chicken was typically Bolivian fare, but my llama steak was essentially a breaded llama wiener schnitzel that had been fried until it became cardboard. I managed to get my fill on rice, corn nuts and Susanne's excess soup instead.

By 10pm, the restaurant host mounted the stage and began introducing the peña performers in Spanish. Meanwhile, Susanne and I sat there, quickly losing energy and enthusiasm. We were both well aware that we'd be getting up before dawn the next morning, and the thought of sitting through a couple hours of music began to seem like a bad idea. To make matters worse, the restaurant would charge a cover during the performance, which again reminded me how strapped for cash we were. "Let's stick around for the opening dance and a song or two," I suggested. "If it's good, we'll stay for a while and deal with getting more money later. If it's bad, we'll get the hell out of Dodge."

The peña began with a quartet of dancers in Aymara costumes performing to a recording of traditional Andean music. I took the recording as a bad sign - why wasn't the band playing the music instead? The quartet performed a rather acrobatic square dance, spinning around at impressive speeds. Their energy served as a reminder of how tired I now was. "I hope they don't try to pull anyone from the audience," I said.

To my horror, one of the women dancers approached our table and reached her hands out to me. Before I could even curse to myself I was pulled onto the dance floor and twirled around at a dizzying pace. Next to me I noticed Susanne was in a similar predicament, desperately trying to keep up with the choreographed antics of the male dancers. The crowded audience clapped and clapped, speeding up the pace of the dance as I wondered what layer of hell for which I was now the opening entertainment. Eventually the song ended; we both politely thanked our dance partners before collapsing into our chairs.

"What on earth just happened," I panted, catching my breath.

"I don't know," Susanne replied, "but it was without a doubt the most embarrassing moment on this entire trip."

The dancers soon gave way to the main act, a band known as Altiplano. As the musicians mounted the stage, the emcee introduced them as "Bolivia's best Andean fusion band." I expected the worst: "Andean fusion? What about an evening of traditional Andean music?" There would be nothing traditional tonight, it seemed. The band picked up their electric guitars and saxophones, diving into their first adult contemporary jazz number.

Neither Susanne nor I had to say anything. I immediately retrieved our bill as we put on our coats as discreetly as possible. We then got up and walked briskly to the door, hoping no one would notice. "Don't look back," I whispered to Susanne. She bit down on her tongue and held in an immense laugh.

As soon as we were back out on the street, the two of us broke out into uncontrolled hysterics. "My god!" Susanne shouted out between heaves of laughter, "That... was... the worst... music... I've... ever... heard!"

"Next time we find ourselves in Bolivia and thinking about going to another peña, remind me to ask first what kind of music it'll be," I said, wiping tears of laughter from my eyes, "If they say 'fusion,' turn around and run."

"And don't... look... back...." Susanne replied, bent over in exhaustion from laughing so much.

Susanne and I eventually regained our composure and walked down Sagárnaga past Plaza San Francisco. As we crossed the Prado I noticed an old campesina camped out along the side of a building. Susanne suggested I offer her the coca leaves I was still carrying around. As we approached her I could hear the campesina muttering to herself in Aymara. I quickly stopped, placed the envelope of leaves next to her and said, "Buenos noches, señora." I looked back as we walked away and saw her peer into the envelope in confusion. "Uh oh," I said to Susanne just as a trio of drunk men in business suits passed by. "Perhaps that wasn't the best idea. I hope I didn't commit a huge faux pas or anything."

We walked down Calle Comercio one last time and reached the southwest corner of Plaza Murillo. Once again there was a contingency of soldiers and barricades at the intersection. At first I thought they weren't going to let us onto the plaza, but they smiled and waved us through. In front of the presidential palace we found two companies of camouflaged soldiers standing at attention. A small group of pedestrians were assembled across the street, watching the soldiers. We approached the crowd to see what was going on. As Susanne attempted to get a better view, I walked near four dogs that were resting on the plaza steps. One of them growled and showed his teeth at me, so I steered clear and rejoined Susanne.

As we settled into a good spot amongst the crowd we realized the soldier we probably cadets, none older than 20 years old. While several MPs stood guard over us with shotguns, the cadets each took turn shouting out responses to their sergeant, who paced back and forth inspecting his troops. The sergeant approached one cadet as he mounted his rifle over his shoulder - the cadet's feet had accidentally turned at an angle during the maneuver. The sergeant then said something in Spanish and gave the cadet a playful whack on the rear with his sword scabbard. The company, including the cadet, all laughed. The sergeant then patted him on the back and had him try the maneuver again.

And so it went, two companies with two sergeants, each practicing their drills in the open, yet they all seemed to be having a fun time of it. I'd never seen anything similar, where sergeants would publicly instruct cadets in a brotherly way, even going so far to make jokes and laugh with the soldiers. It was almost like the Bolivian army was conducting public relations, demonstrating to the people that the military isn't a bunch of hard-nosed killers that they should fear. While Susanne and I quietly whispered to each other trying to figure out exactly what was going on, one of the sergeants raised his sword and blew a whistle. The two companies began to march in slow kick steps, their boots hitting the ground in thunderous coordination. It was a sound I'd never heard before in person, the simultaneous thuds of over a hundred boots separated by about a second each: thump... thump... thump... thump.... A chill went up my spine as the thumps echoed around the courtyard, the soldiers approaching us with each kick step.

After 20 seconds of marching the sergeant shouted out a command that sounded like "Warriors.... Halt!" Each of the 40-man companies immediately ground to a halt, except for one young cadet on the far right end who took an extra step and stood out in front of all the others. The rest of the cadets immediately responded with laughter, claps and whistles. The out-of-step cadet, of course, was quite embarrassed. I could only imaging the ribbing he'd take from his sergeant. To my surprise, though, the sergeant went up to the cadet and playfully pressed the palm of his right hand onto the cadet's chest, causing the young man to laugh as he stepped back into line. It was as if these cadets were being given an easy night away from the lightning-crack discipline that had to be expected of them the rest of the time. The crowd clearly enjoyed it too, smiling and laughing with the cadets.

The companies practiced the same maneuver four or five times: marching in kick-step, getting lectured on what went right and what didn't, then marching again. Susanne and I eventually moved to the far left of the crowd in order to get a closer view of one of the companies. Not long after we reached our new spot the cadets began to march. My entire field of vision transformed into a Leni Reifenstahl film as the long line of soldiers marched directly at me. The rest of the crowd seemed to disappear with each step, as if I were the only person there to witness it. The whole event felt like a special effect, a cinemescopic portrait with echoing surround sound. My moment of solitude ended when I saw one of the MPs in the corner of my eye, standing to my right with a sawed-off pump shotgun. I briefly looked up at him and watched as he stood guard over me. The MP noticed that I was staring at him and looked away in shy embarrassment, almost playfully. These soldiers were really just kids, and this occasion, whatever it was for, gave them the chance to feel that they could be both soldiers and kids, not just one or the other at any given moment. There were few Spanish faces among the cadets; most appeared to be Aymara indians. Despite their youth they all seemed fiercely proud that they were soldiers, that they were the elite who at this particular moment stood watch over both the presidential palace and parliament. It was as if a troop of boot camp privates were given the taste of guarding the White House: they all seemed to be relishing the moment. Almost as much as I was.

We watched the cadets drill in the cool night air for about 45 minutes until one of the sergeants gave the order for them to march into the presidential palace. As the cadets turned and marched away from us, they began to whistle - Bolivia's answer to the theme from Bridge on the River Kwai, I thought to myself. Susanne and I both stood there in amazement until the last soldier entered the presidential compound. The MPs began opening up the barricades in order to allow traffic back onto the plaza. Susanne and I approached one of them, a handsome young man who seemed anxious to see what we wanted. Not really knowing how to ask what happened, I pointed to the area around the palace and said, "Que pasa?" The MP smiled and spoke quickly in Spanish, waving the shotgun in his hand as he talked. From what Susanne and I were able to make of it, he said that the next day there would be a presidential ceremony on the plaza, and it was tradition for first-timer cadets to have an informal, late night drill the evening before the ceremony. I wish I spoke Spanish better, but I believe he ended his explanation by saying something like, "This is a proud moment for them. Thank you for being here for them." He then thanked us again and said goodnight before returning to his duties.

As we walked back to the hotel, I turned to Susanne. "You know," I said, "as we left the peña, even though we were making fun of it I still felt bad we were leaving early - like we were skipping out on the experience. Little did we know that by leaving early we were treated to the best experience of the night."

"And you wanted to return to the hotel early and get some sleep," Susanne said, smiling.

"Yeah," I replied. "I guess I did...."