Bicycle Tour

|

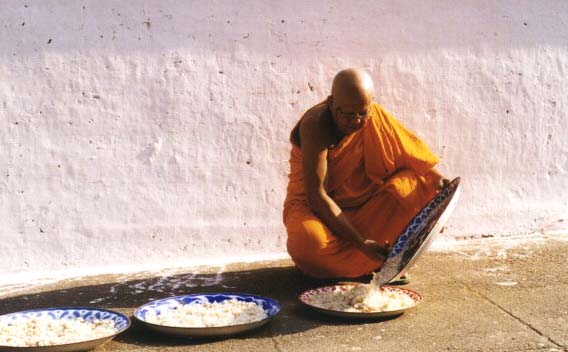

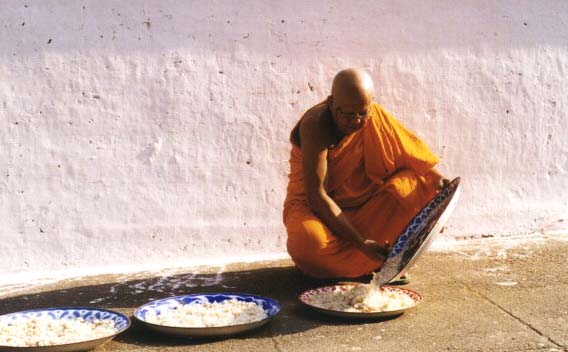

| A monk laying out rice offerings, Luang Prabang |

The next day we started off with a trip to the Lao Royal Palace. King Sisavangvong commissioned the palace in 1904, and his statue still stands on the front lawn. Just past the gates is Wat Mai. It was covered with bamboo scaffolding, but behind the construction we could see the stunning cut and polished glass. Palm trees lined the road up to the Palace steps. According to custom, we took off our shoes and checked our cameras at the door. Before even entering the Palace, we walked along the outside deck. Piles of treasures sat, unlabeled and unprotected by glass, in open-faced rooms. Statues of the Buddha, chests, gold knick knacks. Stacked there without labels, the riches looked more like spoils of war than a collection of national treasures.

Past the grand doorway, we split up and wandered through the immense rooms and dark-wood hallways. Larger-than-life paintings of the last king and queen hung on the wall. A letter from Ho Chi Ming sat on a shelf next to a brightly colored painting of Angkor. The State Room was still decked out in furniture from the 1960's - that sleek, padded, steel blue leather with wooden arm rests that you see in reruns of "I Dream of Genie." As I weaved my way back, I came upon a large room with high ceilings. All the way around, the walls were embossed with cut and polished glass designs. Like figures on a glass tapestry, blood-red warriors rode smurf-blue horses into battle.

Knowing how the last royal family died (betrayed, starved to death in a cave), the palace seemed empty, longing somehow for the shadows that now only hang as oil paintings on the wall. Tourists walked through quietly, respectfully, with their hands clasped behind their backs in that "museum pose." I stared at the glass figures laid into the walls until we decided it was time to go. We collected our shoes and cameras and walked through the palm lined courtyard to the main street.

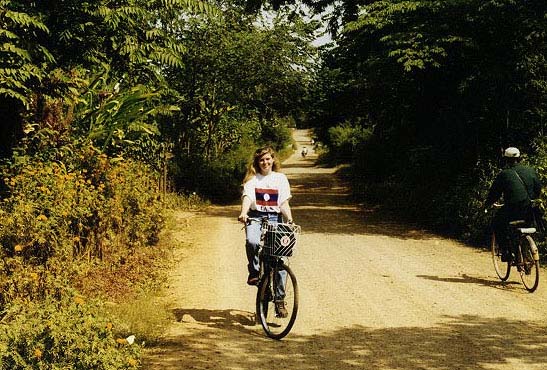

We ended up at this great little bakery where westerners seemed to converge like warthogs at a water hole. Over a couple pieces of banana bread and coconut bread, we talked with a visiting New Yorker and an eccentric Londoner. After lunch, I suggested we rent a couple of bicycles from the shop next door. Actually I suggested we rent motor scooters, but at US $20 a scooter, we opted instead for a pair of bikes with lime green frames, pastel flowered seats and wire metal baskets. Hey, for $3 each, who can complain? And besides, renting those bikes was one of the best things we did on the trip.

We pulled over at a small, shaded wat. The young novice monks gathered at the entrance and welcomed us onto the grounds. Andy and several of the monks practiced their Thai, while I spoke with the few novices who knew English. All the novices were teenagers, between maybe 13 and 17 years old. I asked one of them, "What is the Lao word for butterfly?" He told me, then took a flower between two fingers and taught me the Lao word for flower.

The wat was so secluded, tucked in the hills, far away from the touristed streets of the city. Flocks of butterflies gathered in the bushes. Wooden houses stood in the shadow of the wat. A young novice read aloud to a pair of elderly women. At first I felt like we were intruding. I could tell from the novices' curious expressions that not many tourists stumble into these remote wats. But it seemed that they were just as eager to talk with us as we were to talk with them.

We set out on the dirt road again, past rows of wooden houses and over plank bridges. Luka Bloom's "Acoustic Motorbike" kept playing over and over again in my head. After venturing back out to the main road, we came to the bridge that leads to the airport. The lanky wooden bridge was only wide enough for two lanes of traffic going one way, so to cross, you have to wait your turn. On the very edges of the bridge were narrow foot bridges for pedestrians. We decided to pull over and see the view from there. We walked across the long planks, careful not to step on the pieces of wood that had bowed or broken over the years. Through the gaps, we could see the Mekong flowing 30 feet below us. From the center of the foot bridge, I could see out over the river as it snaked into the hills. Atop a distant hill, a golden wat reflected the midday sun.

|

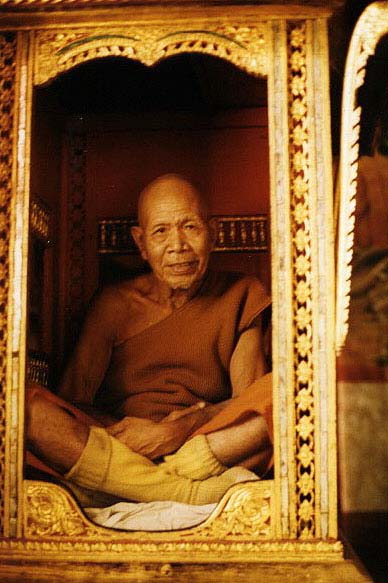

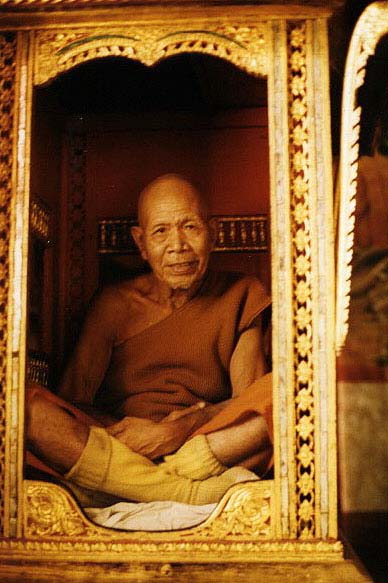

| A Monk in his prayer chamber, Wat Aham |

We rode downhill towards the city, and stopped at a large ornate wat. A novice strung a handful of wet robes along a clothesline. An elderly monk weeded in the garden. I had been disappointed at Angkor that we hadn't meet many monks. Andy told me then, "Don't worry, Luang Prabang is one big monk." He was right. The saffron robe is as common in Luang Prabang as a red tie is in Washington, D.C. Directly in front of the ornate wat, we met an elderly monk with wrinkles as deep as an elephant's. He posed for a picture, then invited us into the wat. We left our shoes at the base of the stairs and walked up, running our hands over the dragon-shaped banister. Inside, the wat was dark and moody. Thin beams of sunlight seeped through the wooden roof and fell onto the central statue of Buddha. Incense burned at the statue's feet and smaller icons stood like guards around it. Our guide maneuvered himself into a painted wooden chariot and beckoned us to take a picture. We donated some money to the wat (especially since the monk had been so nice) and walked downstairs to the garden. A group of children played on the grass, and a little boy in a bright green T-shirt rode his bike up the dirt path.

That was to be our last stop. The cloud cover lifted, and the sun was getting higher. We wove through the mellow traffic, over a bumpy dirt road and downhill to Thanon Phothisalat where we'd rented the bikes four hours before.

|

| Hmong women knitting pandau |

After returning the bicycles and resting up at the hotel, we strolled down the main road. Hmong women sat along the roadside selling pandau, their famous patterned cloth. About two hundred years ago, the Hmong began to trickle down from southern China into Southeast Asia. A large number of them settled in Laos, and when the communist Pathet Lao movement began its insurgency in the early 1960's, the US government recruited the Hmong to fight the communists. Through the 1960s and early 70s, the CIA supplied the Hmong with weapons, training and money. But it was a losing battle, and as the Pathet Lao grew stronger the US began to pull out. After the communists took over Laos in 1975, they began to systematically persecute the Hmong because of the tribe's work with the CIA. Many Hmong escaped to Thailand, where large numbers still live as refugees. Thousands made it to the USA and formed strong Hmong communities in California, Wisconsin and Minnesota. Yet some Hmong remained in Laos. Today there are still reports of Hmong persecution by the Lao communist government, though the international community has done little to investigate it. But you wouldn't know all that just walking through the streets of Luang Prabang, as the Hmong women smile, beckon customers with their hands and display their brightly colored squares of cloth.

|

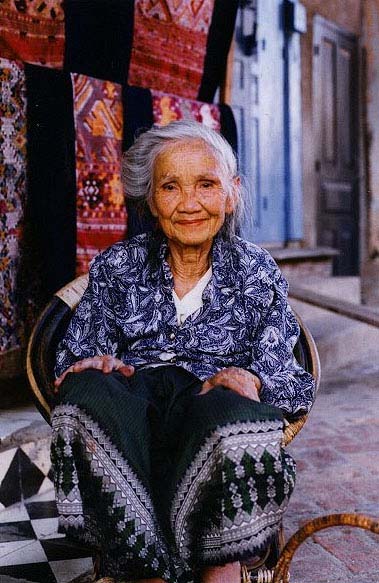

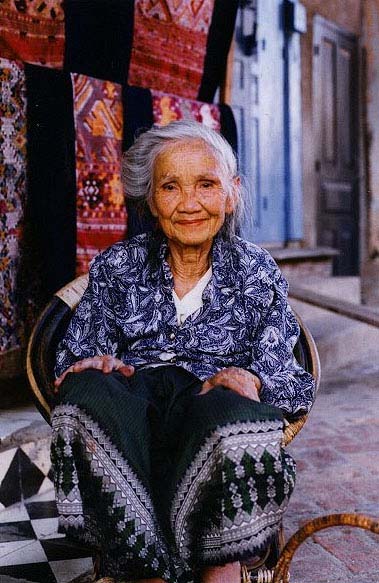

| Lao cloth seller, Luang Prabang |

We continued down the street, looking at postcards and souvenirs. Andy played peek-a-boo with a pair of toddlers. I walked into one shop and found a piece of red cloth, beautifully embroidered in a traditional Lao pattern. The elderly shopkeeper was sitting at the store next door, and as soon as she saw me walk into her shop, she rushed over to me. She couldn't stand up straight and walked completely doubled over, as if when she was standing, her body was still in a sitting position. She drove a hard bargain for the red cloth. She gently insisted that she couldn't go lower than 6000 kip. I didn't feel like haggling and what would I save anyway, a buck, a quarter? 6000 kip was, at that time, $3.50. I figured the cloth was worth much more than that. Besides, we passed her shop so many times during our stay in Luang Prabang that I felt like we knew her. Just the day before I'd asked to take her picture. She was sitting outside her shop, and I was struck by how beautiful she was. Her silvery gray hair was swept back into a bun, and several strands hung over her forehead, just like my grandmother's hair used to hang. She looked graceful, poised and sophisticated just sitting there whittling on the stoop. When I shyly asked if I could take her picture, she held up her hand, buttoned her bottom button, then smiled and nodded that she was ready.

We also picked up a pair of T-shirts since all our other clothes had two weeks worth of wear, tear and sweat in them. I bought one with the Lao flag. Andy's shirt sported the Beer Lao logo. After checking out the various carved wood and embroidered cloth shops, we wandered down to Wat Mai Suwannaphumaham. At the entrance, intricate gold patterns were carved into black pillars. The entire front wall was plated with a gold mural.

Across the yard, a teenage novice pounded a two-foot-round drum while two other young monks clapped cymbals. Another boy, the youngest, hit two dinner-plate-sized gongs with a mallet. Together they created a rapid fire percussion with the soft, low base of the drum and the high, tinny resonance of the gongs. They pounded out the rhythm for some time, and as we turned the corner, we could still hear them playing.

That night we treated ourselves to a meal at the Villa Santi, or Villa de la Princesse as some call it. Owned by the Crown Princess Khampha, this restaurant used to be her residence. Her entire family was starved to death after the communist overthrow, but somehow she survived. In 1991, the government returned the building to her, and she renovated it into a high-priced bed and breakfast. The tables were made out of thick slices of an enormous tree trunk, and the chairs were carved out of a dark, heavy wood. An instrumental version of the Beatles Greatest Hits played softly in the background. "Yesterday" and "Hey Jude" created a strange, eclectic feel.

We sat on the second floor balcony and started off with two bowls of soup. The Soup de la Princess was a buttery broth of greens, mushrooms and onions. The second soup was just incredible, with mushrooms that tasted like finely cut slices of chicken. Then we dug into a plate of soft spring rolls. For our next course, we ordered the Luang Prabang sausage (surprisingly good, with a touch of spice) and baked chicken in banana leaves. The meat was ground and flavored with lemongrass, then stuffed back into the chicken carcass before baking. The rice literally melted in my mouth - as cliche as that sounds, that's how good it was. We split a bottle of Beer Lao, a plate of peeled fruit and a creme caramel. The papaya tasted strangely like buttered popcorn, but the pineapple was perfect. After completely stuffing ourselves we sat back in our chairs, belly out, and stared up at the stars. The whole meal, for both of us, added up to 21,000 kip, just over $12. Pretty high for Laos, but for a first class, multi-course meal in the residence of a Crown Princess, that's a steal.

We took the main thanon back towards the hotel, and as we passed the various shops, a pair of children popped out from behind a pile of cloth. We'd met them before. They were the shop keeper's youngest children, and it seemed they were always playing on the front stoop. The little boy looked about three years old. He had big eyes and a speed racer T-shirt. The little girl looked about four years old. Her thin wispy bangs hung down to her dark eyelashes. We taught them the classic American "gimmee five" hand slap. The little girl caught on quickly, and a couple older kids helped the little boy. Andy waved his arms like a frantic chicken, and the tots imitated him. Their grandmother was the beautiful elderly woman from whom I'd bought the red cloth the day before. She sat on the stoop and laughed along with the kids. Andy extended out his hand, and the kids slapped their little palms against his. The little boy sucked his fingers and gave me a gooey high five. Andy turned to me, his cheeks red from laughing and said, "These have to be the cutest kids on earth."

back towards the hotel, and as we passed the various shops, a pair of children popped out from behind a pile of cloth. We'd met them before. They were the shop keeper's youngest children, and it seemed they were always playing on the front stoop. The little boy looked about three years old. He had big eyes and a speed racer T-shirt. The little girl looked about four years old. Her thin wispy bangs hung down to her dark eyelashes. We taught them the classic American "gimmee five" hand slap. The little girl caught on quickly, and a couple older kids helped the little boy. Andy waved his arms like a frantic chicken, and the tots imitated him. Their grandmother was the beautiful elderly woman from whom I'd bought the red cloth the day before. She sat on the stoop and laughed along with the kids. Andy extended out his hand, and the kids slapped their little palms against his. The little boy sucked his fingers and gave me a gooey high five. Andy turned to me, his cheeks red from laughing and said, "These have to be the cutest kids on earth."

After a good twenty minutes with the kids, we continued down the street under the light of the full moon. A monk in a floppy red hat passed us and said, "Sorry." Andy and I looked at each other and shrugged. We couldn't figure out why a monk would say sorry to us. He was part of a group of monks, making their way past Mount Phousi. He looked back at us as he walked on, but we just didn't know how to respond since we couldn't figure out why he had said sorry. I thought it might be the monk we were supposed to meet the night before at the wat, but why would he say sorry to us? We were the ones who didn't show up... unless he was being sarcastic. But he didn't sound sarcastic. I quickly dismissed that idea. Maybe he was just apologizing for passing us. Who knows.

A couple minutes later another large group of novice monks passed by. We walked at pace with one novice who quickly struck up a conversation. He was only seventeen years old, but he had that confident, wise monk thing going. His English was incredibly good (which was great because our meager Lao was pretty pathetic). He explained that all the monks of Luang Prabang were on their way to a ceremony in honor of the full moon of the eleventh month - a particularly important event for Lao Buddhist monks. The monsoons has officially ended, and they could wander freely again. They shaved their heads the day before also in honor of the full moon. As he spoke, he pointed up to the moon. Fuzzy and yellow, it looked as though it was seated on the top of Phousi. The temple on the hill was silhouetted against the golden sphere. We asked if westerners could go to the ceremony, but he shook his head no. "It's for the villagers," he explained. As much as I wanted to go, I was glad to hear that some ceremonies in the world are still protected from tourists.

and down a dirt road to the river bank. We rode along the river, and soon found ourselves up a hill, in unexplored territory. Traffic picked up on the main street, so we took a detour down a narrow dirt road. School children waved at us and shouted "Sabai dee." One little boy proudly waved a homemade Lao flag - blue and red with a white circle in the center. Swarms of butterflies soared past us. They seemed to be everywhere, darting through the over hanging branches or hovering over flower bushes. We navigated past pot-holes, over wooden plank bridges and right up to some secluded backwoods wats.

and down a dirt road to the river bank. We rode along the river, and soon found ourselves up a hill, in unexplored territory. Traffic picked up on the main street, so we took a detour down a narrow dirt road. School children waved at us and shouted "Sabai dee." One little boy proudly waved a homemade Lao flag - blue and red with a white circle in the center. Swarms of butterflies soared past us. They seemed to be everywhere, darting through the over hanging branches or hovering over flower bushes. We navigated past pot-holes, over wooden plank bridges and right up to some secluded backwoods wats.